<Back to Index>

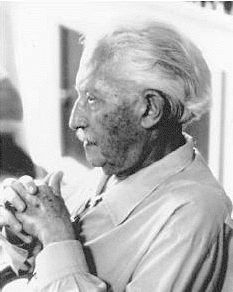

- Psychologist Erik Erikson, 1902

- Painter Nicolas Poussin, 1594

- Prime Minister of Romania Ion Victor Antonescu, 1882

Erik Erikson (June 15, 1902 – May 12, 1994) was a Danish-German-American developmental psychologist and psychoanalyst known for his theory on social development of human beings. He may be most famous for coining the phrase identity crisis. His son, Kai T. Erikson, is a noted American sociologist.

Born in Frankfurt to Danish parents, Erik Erikson's lifelong interest in the psychology of identity may be traced to his childhood. He was born on June 15, 1902 as a result of his mother's extramarital affair, and the circumstances of his birth were concealed from him in his childhood. His mother, Karla Abrahamsen, came from a prominent Jewish family in Copenhagen, her mother Henrietta died when Karla was only 13. Abrahamsen's father, Josef, was a merchant in dried goods. Karla's older brothers Einar, Nicolai, and Axel were active in local Jewish charity and helped maintain a free soup kitchen for indigent Jewish immigrants from Russia. Since Karla Abrahamsen was officially married to Jewish stockbroker Waldemar Isidor Salomonsen at the time, her son, born in Germany, was registered as Erik Salomonsen. There is no more information about his biological father, except that he was a Dane and his given name probably was Erik. It is also suggested that he was married at the time that Erikson was conceived. Following her son's birth, Karla trained to be a nurse, moved to Karlsruhe and in 1904 married a Jewish pediatrician Theodor Homburger. In 1909 Erik Salomonsen became Erik Homburger and in 1911 he was officially adopted by his stepfather.

The development of identity seems

to have been one of Erikson's greatest concerns in his own life as well

as in his theory. During his childhood and early adulthood he was known

as Erik Homburger, and his parents kept the details of his birth a

secret. He was a tall, blond, blue-eyed boy who was raised in the

Jewish religion. At temple school, the kids teased him for being Nordic; at grammar school, they teased him for being Jewish. Erikson was a student and teacher of arts. While teaching at a private school in Vienna, he became acquainted with Anna Freud, the daughter of Sigmund Freud.

Erikson underwent psychoanalysis, and the experience made him decide to

become an analyst himself. He was trained in psychoanalysis at the

Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute and also studied the Montessori method of education, which focused on child development. Following Erikson’s graduation from the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute in 1933, the Nazis had just come to power in Germany, and he emigrated with his wife, first to Denmark and then to the United States, where he became the first child psychoanalyst in Boston. Erikson held positions at Massachusetts General Hospital, the Judge Baker Guidance Center, and at Harvard’s Medical School and Psychological Clinic, establishing a solid reputation as an outstanding clinician. In 1936, Erikson accepted a position at Yale University, where he worked at the Institute of Human Relations and taught at the

Medical School. After spending a year observing children on a Sioux reservation in South Dakota, he joined the faculty of the University of California at Berkeley, where he was affiliated with the Institute of Child Welfare, and opened a private practice as well. While in California, Erikson also studied children of the Yurok Native American tribe. After publishing the book for which Erikson is best known, Childhood and Society, in 1950, he left the University of California when professors there were asked to sign loyalty oaths. He spent ten years working and teaching at the Austen Riggs Center, a prominent psychiatric treatment facility in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he worked with emotionally troubled young people. In

the 1960s, Erikson returned to Harvard as a professor of human

development and remained at the university until his retirement in

1970. In 1973 the National Endowment for the Humanities selected Erikson for the Jefferson Lecture, the U.S. federal government's highest honor for achievement in the humanities. Erikson's lecture was entitled "Dimensions of a New Identity."

Erikson's greatest innovation was to postulate not five stages of development, as Sigmund Freud had done with his psychosexual stages,

but eight. Erik Erikson believed that every human being goes through a

certain number of stages to reach his or her full development,

theorizing eight stages, that a human being goes through from birth to

death. Erikson elaborated Freud's genital stage into adolescence,

and added three stages of adulthood. His widow Joan Serson Erikson

elaborated on his model before her death, adding a ninth stage (old

age) to it, taking into consideration the increasing life expectancy in

Western cultures. Erikson is also credited with being one of the

originators of Ego psychology,

which stressed the role of the ego as being more than a servant of the

id. According to Erikson, the environment in which a child lived was

crucial to providing growth, adjustment, a source of self awareness and

identity. His 1969 book Gandhi's Truth, which focused more on his theory as applied to later phases in the life cycle, won Erikson a Pulitzer Prize and a U.S. National Book Award. Erikson

was a Neo-Freudian. He has been described as an "ego psychologist"

studying the stages of development, spanning the entire lifespan. Each

of Erikson's stages of psychosocial development are marked by a

conflict, for which successful resolution will result in a favourable

outcome, for example, trust vs. mistrust, and by an important event

that this conflict resolves itself around, for example, meaning of

one's life. Favourable

outcomes of each stage are sometimes known as "virtues", a term used,

in the context of Eriksonian work, as it is applied to medicines,

meaning "potencies." For example, the virtue that would emerge from

successful resolution. Oddly, and certainly counter-intuitively,

Erikson's research suggests that each individual must learn how to hold

both extremes of each specific life-stage challenge in tension with one

another, not rejecting one end of the tension or the other. Only when

both extremes in a life-stage challenge are understood and accepted as

both required and useful, can the optimal virtue for that stage

surface. Thus, 'trust' and 'mis-trust' must both be understood and

accepted, in order for realistic 'hope' to emerge as a viable solution

at the first stage. Similarly, 'integrity' and 'despair' must both be

understood and embraced, in order for actionable 'wisdom' to emerge as

a viable solution at the last stage. The Erikson life-stage virtues, in

the order of the stages in which they may be acquired, are: On

ego identity versus Role Confusion, ego identity enables each person to

have a sense of individuality, or as Erikson would say, "Ego identity,

then, in its subjective aspect, is the awareness of the fact that there

is a self-sameness and continuity to the ego's synthesizing methods and

a continuity of one's meaning for others" (1963). Role Confusion, however, is, according to Barbara Engler in her book Personality Theories (2006),

"The inability to conceive of oneself as a productive member of one's

own society". This inability to conceive of oneself as a

productive member is a great danger; it can occur during adolescence

when looking for an occupation. Most

empirical research into Erikson's theories has focused on his views

regarding the attempt to establish identity during adolescence. His

theoretical approach has been studied and supported, particularly

regarding adolescence, by James Marcia. Marcia's work extended Erikson's by distinguishing different forms of

identity, and there is some empirical evidence that those people who

form the most coherent self-concept in adolescence are those who are

most able to make intimate attachments in early adulthood. This

supports Eriksonian theory, in that it suggests that those best

equipped to resolve the crisis of early adulthood are those who have

most successfully resolved the crisis of adolescence.