<Back to Index>

- Chemist Sir William Crookes, 1832

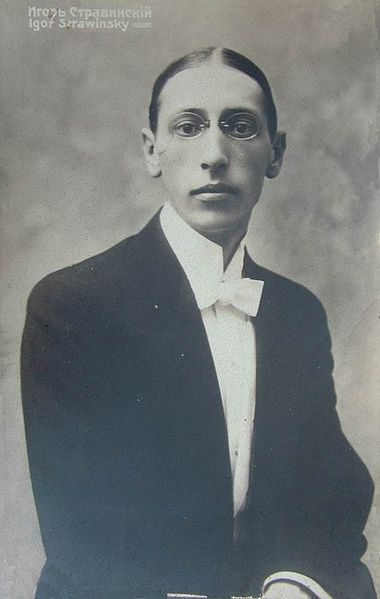

- Composer Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky, 1882

- King of Sweden Charles XII, 1682

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (Russian: Игорь Фёдорович Стравинский) (17 June [O.S. 5 June] 1882 – 6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist, and conductor, widely acknowledged as one of the most important and influential composers of 20th century music. He was a quintessentially cosmopolitan Russian who was named by Time magazine as one of the 100 most influential people of the century. He became a naturalized US citizen in 1946. In addition to the recognition he received for his compositions, he also achieved fame as a pianist and a conductor, often at the premieres of his works.

Stravinsky's compositional career was notable for its stylistic diversity. He first achieved international fame with three ballets commissioned by the impresario Sergei Diaghilev and performed by Diaghilev's Ballets Russes (Russian Ballets):The Firebird (1910), Petrushka (1911/1947), and The Rite of Spring (1913). The Rite, whose premiere provoked a riot, transformed the way in which subsequent composers thought about rhythmic structure, and was largely responsible for Stravinsky's enduring reputation as a musical revolutionary, pushing the boundaries of musical design. After this first Russian phase Stravinsky turned to neoclassicism in the 1920s. The works from this period tended to make use of traditional musical forms (concerto grosso, fugue, symphony), frequently concealed a vein of intense emotion beneath a surface appearance of detachment or austerity, and often paid tribute to the music of earlier masters, for example J.S. Bach and Tchaikovsky. In the 1950s he adopted serial procedures, using the new techniques over his last twenty years. Stravinsky's compositions of this period share traits with all of his earlier output: rhythmic energy, the construction of extended melodic ideas out of a few two- or three-note cells, and clarity of form, of instrumentation, and of utterance.

He

also published a number of books throughout his career, almost always

with the aid of a collaborator, sometimes uncredited. In his 1936

autobiography, Chronicles of My Life, written with the help of Walter Nouvel,

Stravinsky included his infamous statement that "music is, by its very

nature, essentially powerless to express anything at all." With Alexis Roland-Manuel and Pierre Souvtchinsky he wrote his 1939–40 Harvard University Charles Eliot Norton Lectures, which were delivered in French and later collected under the title Poétique musicale in 1942 (translated in 1947 as Poetics of Music). Several interviews in which the composer spoke to Robert Craft were published as Conversations with Igor Stravinsky. They collaborated on five further volumes over the following decade. Stravinsky signed a full agreement with Boosey & Hawkes for his musical copyrights in 1947. Stravinsky was born in 1882 in Oranienbaum (renamed Lomonosov in 1948), Russia, and brought up in Saint Petersburg. His childhood, he recalled in his autobiography, was troubled: "I never came across anyone who had any real affection for me." His father, Fyodor Stravinsky, was a bass singer at the Mariinsky Theater in Saint Petersburg, and

the young Stravinsky began piano lessons and later studied music theory

and attempted some composition. In 1890, Stravinsky saw a performance of Tchaikovsky's ballet The Sleeping Beauty at the Mariinsky Theater; the performance, his first exposure to an orchestra, mesmerized him. At fourteen, he had mastered Mendelssohn's Piano Concerto in G minor, and the next year, he finished a piano reduction of one of Alexander Glazunov's string quartets. Despite his enthusiasm for music, his parents expected him to become a lawyer. Stravinsky enrolled to study law at the University of Saint Petersburg in 1901, but was ill-suited for it, attending fewer than fifty class sessions in four years. After

the death of his father in 1902, he had already begun spending more

time on his musical studies. Because of the closure of the university

in the spring of 1905, in the aftermath of Bloody Sunday, Stravinsky was prevented from taking his law finals, and received only a half-course diploma, in April 1906. Thereafter, he concentrated on music. On the advice of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov,

probably the leading Russian composer of the time, he decided not to

enter the Saint Petersburg Conservatoire; instead, in 1905, he began to

take twice-weekly private tutelage from Rimsky-Korsakov, who became

like a second father to him. These lessons continued until 1908. In

1905 he was betrothed to his cousin Katerina Nossenko, whom he had

known since early childhood. They were married on 23 January 1906, and

their first two children, Fyodor and Ludmilla, were born in 1907 and

1908 respectively. In 1909, his Feu d'artifice (Fireworks), was performed in Saint Petersburg, where it was heard by Sergei Diaghilev, the director of the Ballets Russes in Paris.

Diaghilev was sufficiently impressed to commission Stravinsky to carry

out some orchestrations, and then to compose a full-length ballet score, The Firebird. Stravinsky travelled to Paris in 1910 to attend the premiere of The Firebird. His family soon joined him, and decided to remain in the West for a time. He moved to Switzerland, where he lived until 1920 in Clarens and Lausanne. During this time he composed three further works for the Ballets Russes — Petrushka (1911), written in Lausanne, and The Rite of Spring (1913) and Pulcinella, both written in Clarens. While the Stravinskys were in Switzerland, their second son, Soulima (who later became a minor composer), was born in 1910; and their second

daughter, Maria Milena, was born in 1913. During this last pregnancy,

Katerina was found to have tuberculosis,

and she was placed in a Swiss sanatorium for her confinement. After a

brief return to Russia in July 1914 to collect research materials for Les Noces, Stravinsky left his homeland and returned to Switzerland just before the outbreak of World War I brought

about the closure of the borders. He was not to return to Russia for

nearly fifty years. Stravinsky was one of the few Eastern Orthodox or

Russian Orthodox community representatives living in Switzerland at

that time and is still remembered as such in Switzerland to date. He had a significant artistic relationship with the Swiss philanthropist Werner Reinhart. He approached Reinhart for financial assistance when he was writing Histoire du soldat (The Soldier’s Tale). The first performance was conducted by Ernest Ansermet on 28 September 1918, at the Theatre Municipal de Lausanne.

Werner Reinhart sponsored and to a large degree underwrote this

performance. In gratitude, Stravinsky dedicated the work to Reinhart, and even gave him the original manuscript. Reinhart continued his support of Stravinsky's work in 1919 by funding a series of concerts of his recent chamber music. These included a suite of five numbers from The Soldier's Tale, arranged for clarinet, violin, and piano, which was a nod to Reinhart, who was an excellent amateur clarinettist. The

suite was first performed on 8 November 1919, in Lausanne, long before

the better-known suite for the seven original performers became widely

known. In gratitude for Reinhart’s ongoing support, Stravinsky dedicated his Three Pieces for Clarinet (composed October – November 1918) to Reinhart. Reinhart later founded a music library of Stravinskiana at his home in Winterthur. Stravinsky moved to France in

1920, where he formed a business and musical relationship with the

French piano manufacturer Pleyel. Pleyel essentially acted as his agent

in collecting mechanical royalties for his works, and in return

provided him with a monthly income and a studio space in which to work

and to entertain friends and business acquaintances. Stravinsky also

arranged (and to some extent re-composed) many of his early works for

the Pleyela, Pleyel's brand of player piano.

Stravinsky did so in a way that made full use of the piano's 88 notes,

without regard for the number or span of human fingers and hands. These

were not recorded rolls, but were instead marked up from a combination

of manuscript fragments and handwritten notes by the French musician,

Jacques Larmanjat (musical director of Pleyel's roll department). While

many of these works are now part of the standard repertoire, at the

time many orchestras found his music beyond their capabilities and

unfathomable. Major compositions issued on Pleyela piano rolls include The Rite of Spring, Petrushka, Firebird, Les Noces and Song of the Nightingale. During the 1920s he also recorded Duo-Art rolls for the Aeolian Company in both London and New York, not all of which survive. After a short stay near Paris,

Stravinsky moved with his family to the south of France. He returned to

Paris in 1934, to live at the rue Faubourg-St. Honoré.

Stravinsky later remembered this as his last and unhappiest European

address; his wife's tuberculosis infected his eldest daughter Ludmila,

and Stravinsky himself. Ludmila died in 1938, Katerina in the following

year. Stravinsky spent five months in hospital, during which time his

mother also died. Although his marriage to Katerina endured for 33 years, Vera de Bosset (1888–1982), the true love of his life and later his partner until his death, became

his second wife. When Stravinsky met Vera in Paris in February 1921,

she was married to the painter and stage designer Serge Sudeikin;

however, they soon began an affair which led to her leaving her

husband. From then until Katerina's death from cancer in 1939,

Stravinsky led a double life, spending some of his time with his first

family and the rest with Vera. Katerina soon learned of the

relationship and accepted it as inevitable and permanent. He became a

French citizen in 1934. During his latter years in Paris, Stravinsky had developed professional relationships with key people in the United States; he was already working on the Symphony in C for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and had agreed to lecture at Harvard during the academic year of 1939–40. When World War II broke

out in September 1939, Stravinsky moved to the United States. Vera

followed him early in the next year and they were married in Bedford, MA, USA, on 9 March 1940. Stravinsky settled down in the Los Angeles area (1260 North Wetherly Drive, West Hollywood) where, in the end, he spent more time as a resident than any other city during his lifetime. He became a naturalized citizen in

1946. Stravinsky had adapted to life in France, but moving to America

at the age of 58 was a very different prospect. For a time, he

preserved a ring of emigré Russian

friends and contacts, but eventually found that this did not sustain

his intellectual and professional life. He was drawn to the growing

cultural life of Los Angeles, especially during World War II, when so

many writers, musicians, composers, and conductors settled in the area;

these included Otto Klemperer, Thomas Mann, Franz Werfel, George Balanchine and Arthur Rubinstein. He lived fairly near to Arnold Schoenberg,

though he did not have a close relationship with him. Bernard Holland

notes that he was especially fond of British writers who often visited

him in Beverly Hills, "like W. H. Auden, Christopher Isherwood, Dylan Thomas (who shared the composer's taste for hard spirits) and, especially, Aldous Huxley, with whom Stravinsky spoke in French." He settled into life in Los Angeles and sometimes conducted concerts with the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the famous Hollywood Bowl as well as throughout the U.S. When he planned to write an opera with W.H. Auden, the need to acquire more familiarity with the English-speaking world coincided with his meeting the conductor and musicologist Robert Craft. Craft lived with Stravinsky until the composer's death, acting as interpreter, chronicler, assistant conductor, and factotum for countless musical and social tasks. On April 15, 1940, Stravinsky's unconventional major seventh chord in his arrangement of the Star-Spangled Banner led to his arrest by the Boston police for violating a federal law that prohibited the reharmonization of the National Anthem. Stravinsky was on the lot of Paramount Pictures when the musical score to the 1956 film The Court Jester (starring Danny Kaye) was being recorded. The red “recording in progress” light was illuminated to ensure no interruptions, Vic Schoen,

the composer of the score, started to conduct a cue but noticed that

the entire orchestra had turned to look at Stravinsky, who had just

walked into the studio. Schoen said,

“The entire room was astonished to see this short little man with a big

chest walk in and listen to our session. I later talked with him after

we were done recording. We went and got a cup of coffee together. After

listening to my music Stravinsky had told me ‘You have broken all the

rules’. At the time I didn’t understand his comment because I had been

self-taught. It took me years to figure out what he had meant." In 1959, Stravinsky was awarded the Sonning Award, Denmark's highest musical honour. In 1962, he accepted an invitation to return to Leningrad (today known as Saint Petersburg) for a series of concerts. He spent more than two hours speaking with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, who urged him to return to the Soviet Union. Despite the invitation, Stravinsky remained settled in the West. It was during the 1960s that Stravinsky became mentor for Warren Zevon. Zevon occasionally studied Classical music in Stravinsky's home. In 1969, he moved to New York where he lived his last years at the Essex House. Two years later, he died at the age of 88 in New York City and was buried in Venice on the cemetery island of San Michele. His grave is close to the tomb of his long-time collaborator Sergei Diaghilev.

Stravinsky's professional life had encompassed most of the 20th

century, including many of its modern classical music styles, and he

influenced composers both during and after his lifetime. He has a star

on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6340 Hollywood Boulevard and posthumously received the Grammy Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1987. Stravinsky

displayed an inexhaustible desire to explore and learn about art,

literature, and life. This desire manifested itself in several of his

Paris collaborations. Not only was he the principal composer for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, but he also collaborated with Pablo Picasso (Pulcinella, 1920), Jean Cocteau (Oedipus Rex, 1927) and George Balanchine (Apollon musagète,

1928). His taste in literature was wide, and reflected his constant

desire for new discoveries. The texts and literary sources for his work

began with a period of interest in Russian folklore, progressed to classical authors and the Latin liturgy, and moved on to contemporary France (André Gide, in Persephone) and eventually English literature, including Auden, T. S. Eliot and medieval English verse. At the end of his life, he set Hebrew scripture in Abraham and Isaac. Patronage was never far away. In the early 1920s, Leopold Stokowski gave Stravinsky regular support through a pseudonymous "benefactor". The composer was also able to attract commissions: most of his work from The Firebird onwards was written for specific occasions and was paid for generously. Stravinsky

proved adept at playing the part of "man of the world", acquiring a

keen instinct for business matters and appearing relaxed and

comfortable in many of the world's major cities. Paris, Venice, Berlin, London, Amsterdam and New York City all

hosted successful appearances as pianist and conductor. Most people who

knew him through dealings connected with performances spoke of him as

polite, courteous and helpful. For example, Otto Klemperer, who knew Arnold Schoenberg well, said that he always found Stravinsky much more co-operative and easy to deal with. At the same time, he had a marked disregard for those he perceived to be his social inferiors: Robert Craft was

embarrassed by his habit of tapping a glass with a fork and loudly

demanding attention in restaurants. Although a notorious philanderer

(who was rumoured to have affairs with high-profile partners such as Coco Chanel), Stravinsky was also a family man who devoted considerable amounts of his time and expenditure to his sons and daughters. Stravinsky was also a devout member of the Russian Orthodox Church all

throughout his life, remarking at one time, "Music praises God. Music

is well or better able to praise him than the building of the church

and all its decoration; it is the Church's greatest ornament."