<Back to Index>

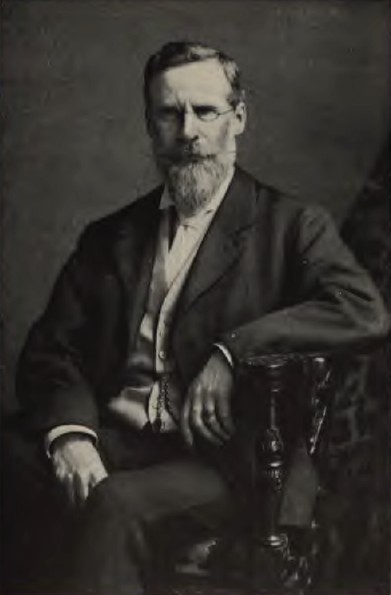

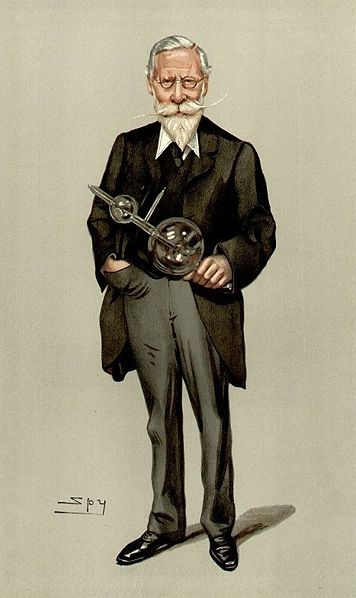

- Chemist Sir William Crookes, 1832

- Composer Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky, 1882

- King of Sweden Charles XII, 1682

Sir William Crookes, OM, FRS (17 June 1832 – 4 April 1919) was a chemist and physicist who attended the Royal College of Chemistry, in London, and worked on spectroscopy. He was pioneer of vacuum tubes, inventing the Crookes tube.

William

Crookes was born in London, the eldest son of Joseph Crookes, a tailor

of north-country origin whose second wife was Mary Scott. From

1850 to 1854 he filled the position of assistant in the college, and

soon embarked upon original work, not in organic chemistry where the

inspiration of his teacher, August Wilhelm von Hofmann, might have been expected to lead him, but on new compounds of selenium. These formed the subject of his first published papers in 1851. Leaving the Royal College, he became superintendent of the meteorological department at the Radcliffe Observatory in Oxford in 1854, and in 1855 was appointed lecturer in chemistry at the Chester Diocesan Training College. Married

now and living in London, he was devoted mainly to independent work.

After 1880, he lived at 7 Kensington Park Gardens, where all his later

work was carried out in his private laboratory. Crookes's life was one

of unbroken scientific activity. The breadth of his interests, ranging

over pure and applied science, economic and practical problems, and

psychical research, made him a well-known personality, and he received

many public and academic honours. In 1859, he founded the Chemical News,

a science magazine which he edited for many years and conducted on much

less formal lines than is usual with journals of scientific societies. Crookes was knighted in 1897, and in 1910 received the Order of Merit. In 1861, Crookes discovered a previously unknown element with a bright green emission line in its spectrum and named the element thallium, from the Greek thallos, a green shoot. Crookes also identified the first known sample of helium, in 1895. He was the inventor of the Crookes radiometer, which today is made and sold as a novelty item. He also developed the Crookes tubes, investigating canal rays. In his investigations of the conduction of electricity in

low pressure gases, he discovered that as the pressure was lowered, the

negative electrode (cathode) appeared to emit rays (the so-called cathode rays, now known to be a stream of free electrons, and used in cathode ray display devices). As these examples indicate, he was a pioneer in the construction and use of vacuum tubes for the study of physical phenomena. He was, as a consequence, one of the first scientists to investigate what are now called plasmas. He also devised one of the first instruments for the study of nuclear radioactivity, the spinthariscope.

Crookes worked over both fields of chemistry and physics. Its salient characteristic was the originality of conception of his experiments, and the skill of their execution. Crookes was always more effective in experiment than in interpretation. The method of spectral analysis, introduced by Bunsen and Kirchhoff,

was received by Crookes with great enthusiasm and to great effect. His

first important discovery was that of the element thallium, announced

in 1861, and made with the help of spectroscopy. By this work his

reputation became firmly established, and he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1863. Crookes'

attention had been attracted to the vacuum balance in the course of

thallium research. He soon discovered the phenomenon upon which depends

the action of the Crookes radiometer,

in which a system of vanes, each blackened on one side and polished on

the other, is set in rotation when exposed to radiant energy. Crookes

did not, however, provide the true explanation of this apparent

"attraction and repulsion resulting from radiation". He published numerous papers on spectroscopy and conducted research on a variety of minor subjects. In addition to various technical books, he wrote a standard treatise on Select Methods in Chemical Analysis in 1871, and a small book on diamonds in 1909. Crookes investigated the properties of cathode rays, showing that they travel in straight lines, cause phosphorescence in

objects upon which they impinge, and by their impact produce great

heat. He believed that he had discovered a fourth state of matter,

which he called "radiant matter", but his theoretical views on the

nature of "radiant matter" proved to be mistaken. He believed the rays

to consist of streams of particles of ordinary molecular magnitude. It

remained for Sir J.J. Thomson to discover their subatomic nature, and to prove that cathode rays consist of streams of negative electrons, that is, of negatively electrified particles whose mass is only 1/1840 that of a hydrogen atom.

Nevertheless, Crookes's experimental work in this field was the

foundation of discoveries which eventually changed the whole of

chemistry and physics. In 1903, Crookes turned his attention to the newly discovered phenomena of radioactivity, achieving the separation from uranium of its active transformation product, uranium-X (later established to be protactinium). He observed the gradual decay of

the separated transformation product, and the simultaneous reproduction

of a fresh supply in the original uranium. At about the same time as

this important discovery, he observed that when "p-particles", ejected from radio-active substances, impinge upon zinc sulfide,

each impact is accompanied by a minute scintillation, an observation

which forms the basis of one of the most useful methods in the

technique of radioactivity. In 1870 Crookes decided that science had a duty to study preternatural phenomena associated with Spiritism. Judging from family letters, Crookes had already developed a

favorable view of Spiritism by 1869.

In this he was possibly influenced by the untimely death of his young

brother Philip in 1867 at age 21 from yellow fever contracted while on

an expedition to lay a telegraph cable from Cuba to Florida. Nevertheless, he was determined to conduct his inquiry

impartially and described the conditions he imposed on mediums as

follows: "It must be at my own house, and my own selection of friends

and spectators, under my own conditions, and I may do whatever I like

as regards apparatus". Among the mediums he

studied were Kate Fox, Florence Cook, and Daniel Dunglas Home.

Among the phenomena he witnessed were

movement of bodies at a distance, rappings, changes in the weights of

bodies, levitation, appearance of luminous objects, appearance of

phantom figures, appearance of writing without human agency, and

circumstances which "point to the agency of an outside intelligence".

To find support and assistance for his research, he joined the Society for Psychical Research. His

report on this research in 1874, concluded that these phenomena could

not be explained as conjuring, and that further research would be

useful. Crookes was not alone in his views. Fellow scientists who came

to believe in Spiritualism included Alfred Russel Wallace, Oliver Joseph Lodge, Lord Rayleigh, and William James. Nevertheless, most scientists were convinced that

Spiritism was fraudulent, and Crookes' final report so outraged the

scientific establishment "that there was talk of depriving him of his

Fellowship of the Royal Society." Crookes then became much more

cautious and didn't discuss his views publicly until 1898, when he felt

is position was secure. From that time until his death in 1919, letters

and interviews show that Crookes was a believer in Spiritism. In

1856 he married Ellen, daughter of William Humphrey, of Darlington, by

whom he fathered three sons and a daughter. He died in London on 4

April 1919, two years after his wife. He is buried in London's Brompton Cemetery.