<Back to Index>

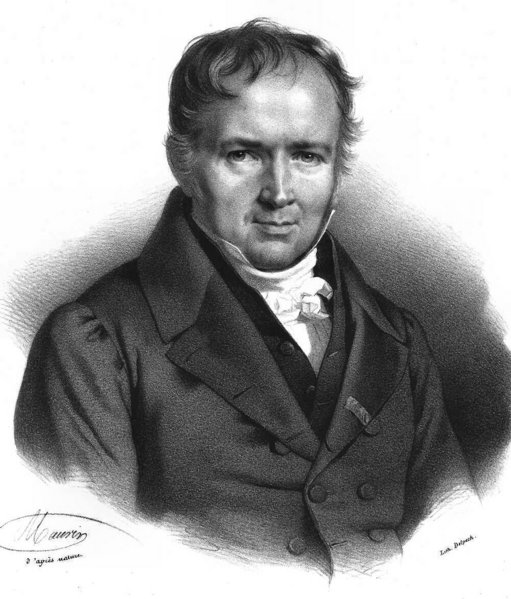

- Mathematician Siméon Denis Poisson, 1781

- Architect Pier Luigi Nervi, 1891

- President of the Generalitat de Catalunya Lluís Companys i Jover, 1882

Siméon-Denis Poisson (21 June 1781 – 25 April 1840), was a French mathematician, geometer, and physicist.

Poisson was born in Pithiviers, Loiret.

In 1798, he entered the École Polytechnique in Paris as first in his year, and immediately began to attract the notice of the professors of the school, who left him free to make his own choices as to what he would study. In 1800, less than two years after his entry, he published two memoirs, one on Étienne Bézout's method of elimination, the other on the number of integrals of a finite difference equation. The latter was examined by Sylvestre-François Lacroix and Adrien-Marie Legendre, who recommended that it should be published in the Recueil des savants étrangers, an unprecedented honour for a youth of eighteen. This success at once procured entry for Poisson into scientific circles. Joseph Louis Lagrange, whose lectures on the theory of functions he attended at the École Polytechnique, recognized his talent early on, and became his friend (the Mathematics Genealogy Project lists Lagrange as his advisor, but this may be an approximation); while Pierre-Simon Laplace, in whose footsteps Poisson followed, regarded him almost as his son. The rest of his career, till his death in Sceaux near Paris, was almost entirely occupied by the composition and publication of his many works and in fulfilling the duties of the numerous educational positions to which he was successively appointed.

Immediately after finishing his studies at the École Polytechnique, he was appointed répétiteur (teaching assistant) there, a position which he had occupied as an amateur while still a pupil in the school; for his schoolmates had made a custom of visiting him in his room after an unusually difficult lecture to hear him repeat and explain it. He was made deputy professor (professeur suppléant) in 1802, and, in 1806 full professor succeeding Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier, whom Napoleon had sent to Grenoble. In 1808 he became astronomer to the Bureau des Longitudes; and when the Faculté des Sciences was instituted in 1809 he was appointed professor of rational mechanics (professeur de mécanique rationelle). He went on to become a member of the Institute in 1812, examiner at the military school (École Militaire) at Saint-Cyr in 1815, graduation examiner at the École Polytechnique in 1816, councillor of the university in 1820, and geometer to the Bureau des Longitudes succeeding Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1827.

In 1817, he married Nancy de Bardi and with her he had four children. His father, whose early experiences had led him to hate aristocrats, bred him in the stern creed of the First Republic. Throughout the Revolution, the Empire, and the following restoration, Poisson was not interested in politics, concentrating on mathematics. He was appointed to the dignity of baron in 1821; but he neither took out the diploma or used the title. In 1823, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. The revolution of July 1830 threatened him with the loss of all his honours; but this disgrace to the government of Louis-Philippe was adroitly averted by François Jean Dominique Arago, who, while his "revocation" was being plotted by the council of ministers, procured him an invitation to dine at the Palais Royal, where he was openly and effusively received by the citizen king, who "remembered" him. After this, of course, his degradation was impossible, and seven years later he was made a peer of France, not for political reasons, but as a representative of French science.

Like many scientists of his time, he was an atheist.

As

a teacher of mathematics Poisson is said to have been extraordinarily

successful, as might have been expected from his early promise as a répétiteur at

the École Polytechnique. As a scientific worker, his

productivity has rarely if ever been equalled. Notwithstanding his many

official duties, he found time to publish more than three hundred

works, several of them extensive treatises, and many of them memoirs

dealing with the most abstruse branches of pure mathematics, applied mathematics, mathematical physics, and rational mechanics. A

list of Poisson's works, drawn up by himself, is given at the end of

Arago's biography. All that is possible is a brief mention of the more

important ones.

It was in the application of mathematics to physics that his greatest services to science were performed. Perhaps the most original, and certainly the most permanent in their influence, were his memoirs on the theory of electricity and magnetism, which virtually created a new branch of mathematical physics. Next (or in the opinion of some, first) in importance stand the memoirs on celestial mechanics, in which he proved himself a worthy successor to Pierre-Simon Laplace. The most important of these are his memoirs Sur les inégalités séculaires des moyens mouvements des planètes, Sur la variation des constantes arbitraires dans les questions de mécanique, both published in the Journal of the École Polytechnique (1809); Sur la libration de la lune, in Connaissances des temps (1821), etc.; and Sur le mouvement de la terre autour de son centre de gravité, in Mémoires de l'Académie (1827), etc. In the first of these memoirs Poisson discusses the famous question of the stability of the planetary orbits, which had already been settled by Lagrange to the first degree of approximation for the disturbing forces. Poisson showed that the result could be extended to a second approximation, and thus made an important advance in planetary theory. The memoir is remarkable in as much as it roused Lagrange, after an interval of inactivity, to compose in his old age one of the greatest of his memoirs, entitled Sur la théorie des variations des éléments des planètes, et en particulier des variations des grands axes de leurs orbites. So highly did he think of Poisson's memoir that he made a copy of it with his own hand, which was found among his papers after his death. Poisson made important contributions to the theory of attraction.