<Back to Index>

- Physicist Wander Johannes de Haas, 1878

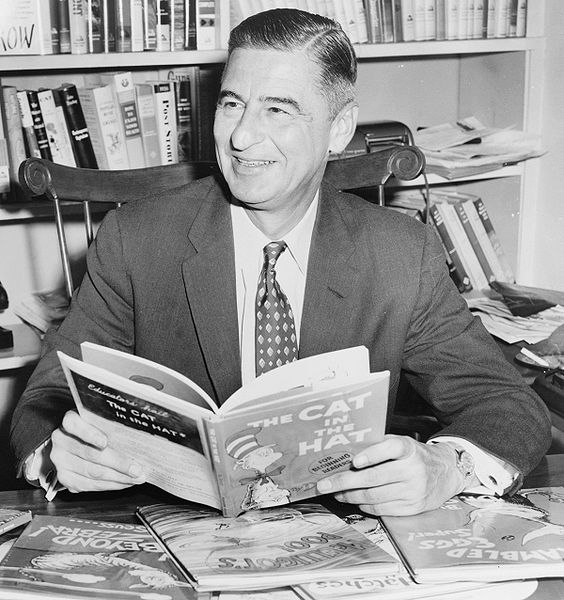

- Writer Theodor Seuss Geisel, 1904

- President of the Soviet Union Mikhail Sergeyevich Corbachev, 1931

Theodor Seuss Geisel (March 2, 1904 – September 24, 1991) was an American writer and cartoonist most widely known for his children's books written under the pen name Dr. Seuss. He published over 60 children's books, which were often characterized by imaginative characters, rhyme, and frequent use of trisyllabic meter. His most celebrated books include the bestselling Green Eggs and Ham, The Cat in the Hat, and One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish. Numerous adaptations of his work have been created, including eleven television specials, three feature films, and a Broadway musical. Geisel also worked as an illustrator for advertising campaigns, most notably for Flit and Standard Oil, and as a political cartoonist for PM, a New York City newspaper. During World War II, he worked in an animation department of the U.S Army, where he wrote Design for Death, a film that later won the 1947 Academy Award for Documentary Feature. Theodor Seuss Geisel was born on March 2, 1904, in Springfield, Massachusetts to Henrietta Seuss and Theodor Robert Geisel. His father, the son of German immigrants, managed the family brewery and after Theodor was married, supervised Springfield's public park system. Geisel was raised in the Lutheran faith and remained a member of the denomination his entire life. He attended Springfield's Central High School and entered Dartmouth College in fall 1921 as a member of the Class of 1925 and joined Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity. At Dartmouth, Geisel joined the humor magazine Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern, eventually rising to the rank of editor-in-chief. While at Dartmouth, Geisel was caught drinking gin with nine friends in his room, violating national Prohibition laws of the time. As a result, the school insisted that he resign from all extracurricular activities. In order to continue his work on the Jack-O-Lantern without

the administration's knowledge, Geisel began signing his work with the

pen name "Seuss"; his first work signed as "Dr. Seuss" appeared after

he graduated, six months into his work for humor magazine The Judge where his weekly feature Birdsies and Beasties appeared. Geisel

was encouraged in his writing by professor of Rhetoric W. Benfield

Pressey, whom he described as his "big inspiration for writing" at

Dartmouth. After Dartmouth, he entered Lincoln College, Oxford, intending to earn a Doctor of Philosophy in literature. At Oxford he met his future wife Helen Palmer; he married her in 1927, and returned to the United States without earning the degree. He began submitting humorous articles and illustrations to Judge, The Saturday Evening Post, Life, Vanity Fair, and Liberty. One notable "Technocracy Number" made fun of the Technocracy movement and featured satirical rhymes at the expense of Frederick Soddy. He became nationally famous from his advertisements for Flit,

a common insecticide at the time. His slogan, "Quick, Henry, the Flit!"

became a popular catch phrase. Geisel supported himself and his wife

through the Great Depression by drawing advertising for General Electric, NBC, Standard Oil, and many other companies. In 1935, he wrote and drew a short-lived comic strip called Hejji. In

1937, while Geisel was returning from an ocean voyage to Europe, the

rhythm of the ship's engines inspired the poem that became his first

book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. Geisel wrote three more children's books before World War II, two of which are, atypically for him, in prose. As World War II began, Geisel turned to political cartoons, drawing over 400 in two years as editorial cartoonist for the left-wing New York City daily newspaper, PM. Geisel's political cartoons, later published in Dr. Seuss Goes to War, opposed the viciousness of Hitler and Mussolini and were highly critical of isolationists, most notably Charles Lindbergh, who opposed American entry into the war. One cartoon depicted all Japanese Americans as latent traitors or fifth-columnists,

while at the same time other cartoons deplored the racism at home

against Jews and blacks that harmed the war effort. His cartoons were

strongly supportive of President Roosevelt's conduct of the war,

combining the usual exhortations to ration and contribute to the war

effort with frequent attacks on Congress (especially the Republican

Party), parts of the press (such as the New York Daily News andChicago Tribune), and others for criticism of Roosevelt, criticism of aid to the Soviet Union, investigation of suspected Communists, and other offenses that he depicted as leading to disunity and helping the Nazis, intentionally or inadvertently. In 1942, Geisel turned his energies to direct support of the U.S. war effort. First, he worked drawing posters for the Treasury Department and the War Production Board. Then, in 1943, he joined the Army and was commander of the Animation Dept of the First Motion Picture Unit of the United States Army Air Forces, where he wrote films that included Your Job in Germany, a 1945 propaganda film about peace in Europe after World War II, Our Job in Japan, and the Private Snafu series of adult army training films. While in the Army, he was awarded the Legion of Merit. Our Job in Japan became the basis for the commercially released film, Design for Death (1947), a study of Japanese culture that won the Academy Award for Documentary Feature. Gerald McBoing-Boing, which was based on an original story by Seuss, won the Academy Award for Animated Short Film. After the war, Geisel and his wife moved to La Jolla, California. Returning to children's books, he wrote many works, including such children's favorites as If I Ran the Zoo, (1950), Scrambled Eggs Super! (1953), On Beyond Zebra! (1955), If I Ran the Circus (1956), and How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1957). Although he received numerous awards throughout his career, Geisel won neither the Caldecott Medal nor the Newbery Medal. Three of his titles from this period were, however, chosen as Caldecott runners-up (now referred to as Caldecott Honor books): McElligot's Pool (1947), Bartholomew and the Oobleck (1949), and If I Ran the Zoo (1950). At the same time, an important development occurred that influenced much of Geisel's later work. In May 1954, Life magazine published a report on illiteracy among

school children, which concluded that children were not learning to

read because their books were boring. Accordingly, William Ellsworth

Spaulding, a textbook editor at Houghton Mifflin who later became its

Chairman, compiled a list of 348 words he felt were important for

first-graders to recognize and asked Geisel to cut the list to 250

words and write a book using only those words. Spaulding challenged Geisel to "bring back a book children can't put down." Nine months later, Geisel, using 236 of the words given to him, completed The Cat in the Hat. This book was a tour de force—it

retained the drawing style, verse rhythms, and all the imaginative

power of Geisel's earlier works, but because of its simplified

vocabulary could be read by beginning readers. Geisel went on to write

many other children's books, both in his new simplified-vocabulary

manner (sold as Beginner Books) and in his older, more elaborate style. On

October 23, 1967, suffering from a long struggle with illnesses

including cancer, Geisel's wife, Helen Palmer Geisel, committed suicide. Geisel

married Audrey Stone Dimond on June 21, 1968. Though he devoted most of

his life to writing children's books, Geisel never had any children. He

would say, when asked about this, "You have 'em; I'll entertain 'em." Geisel died, following several years of illness, in San Diego, California on September 24, 1991. He was cremated, and his ashes were scattered. On December 1, 1995 UCSD's University Library Building was renamed Geisel Library in

honor of Geisel and Audrey for the generous contributions they have

made to the library and their devotion to improving literacy.