<Back to Index>

- Physicist Wander Johannes de Haas, 1878

- Writer Theodor Seuss Geisel, 1904

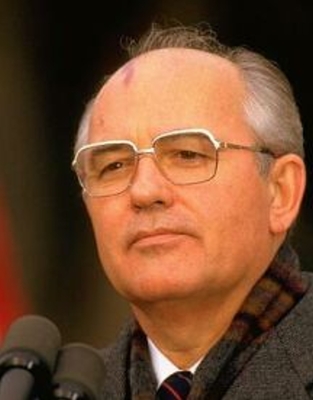

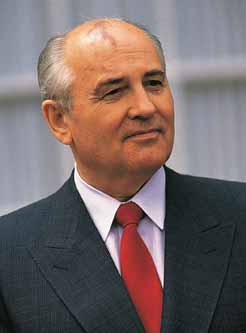

- President of the Soviet Union Mikhail Sergeyevich Corbachev, 1931

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (Russian: Михаил Сергеевич Горбачёв; born 2 March 1931) was the second-to-last General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, serving from 1985 until 1991, and the last head of state of the USSR, serving from 1988 until its collapse in 1991. He was the only Soviet leader to have been born after the October Revolution of 1917. In 1989, he became the first soviet leader to visit China since the 1960s.

Gorbachev was born in Stavropol Krai into a peasant family, and in his teens operated combine harvesters on collective farms. He graduated from Moscow State University in 1955 with a degree in law. While in college, he joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union,

and soon became very active within it. In 1970, he was appointed the

First Party Secretary of the Stavropol Kraikom, First Secretary to the

Supreme Soviet in 1974, and appointed a member of Politburo in 1979. After the deaths, within three years, of Soviet Leaders Leonid Brezhnev, Yuri Andropov, and Konstantin Chernenko,

Gorbachev was elected General Secretary by Politburo in 1985. Already

before he reached the post, he had occasionally been mentioned in

western newspapers as a likely next leader and a man of the younger

generation at the top level. Gorbachev's attempts at reform as well as

summit conferences with United States President Ronald Reagan and his reorientation of Soviet strategic aims contributed to the end of the Cold War, ended the political supremacy of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1990. In September 2008 Gorbachev and billionaire Alexander Lebedev announced they would form the Independent Democratic Party of Russia together, and in May 2009 Gorbachev announced that the launch was imminent. This is Gorbachev's third attempt to establish a political party of significance in Russian politics after having started the Social Democratic Party of Russia in 2001 and the Union of Social-Democrats in 2007. Gorbachev attended the important twenty-second Party Congress in October 1961, where Nikita Khrushchev announced

a plan to surpass the U.S. in per capita production within twenty

years. At this point in his life, Gorbachev would rise in the Communist

League hierarchy and worked his way up through territorial leagues of

the party. He was promoted to Head of the Department of Party Organs in

the Stavropol Agricultural Kraikom in 1963.

In 1970, he was appointed First Party Secretary of the Stavropol

Kraikom, a body of the CPSU, becoming one of the youngest provincial

party chiefs in the nation. In

this position he helped reorganise the collective farms, improve

workers' living conditions, expand the size of their private plots, and

give them a greater voice in planning. He was soon made a member of the Communist Party Central Committee in 1971. Three years later, in 1974, he was made a Representative to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union and

Chairman of the Standing Commission on Youth Affairs. He was

subsequently appointed to the Central Committee's Secretariat for

Agriculture in 1978, replacing Fyodor Kulakov, who had supported

Gorbachev's appointment, after Kulakov died of a heart attack. In 1979, Gorbachev was promoted to the Politburo,

the highest authority in the country, and received full membership in

1980. Gorbachev owed his steady rise to power to the patronage of Mikhail Suslov, the powerful chief ideologist of the CPSU. During Yuri Andropov's tenure as General Secretary (1982–1984), Gorbachev became one of the Politburo's most visible and active members. With

responsibility over personnel, working together with Andropov, 20

percent of the top echelon of government ministers and regional

governors were replaced, often with younger men. During this time Grigory Romanov, Nikolai Ryzhkov, and Yegor Ligachev were elevated, the latter two working closely with Gorbachev, Ryzhkov on economics, Ligachev on personnel. In 1972, he headed a Soviet delegation to Belgium, and three years later he led a delegation to West Germany; in 1983 he headed a delegation to Canada to meet with Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and members of the Commons and Senate. In 1984, he travelled to the United Kingdom, where he met British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Upon Andropov's death in 1984, the aged Konstantin Chernenko took power; after his death the following year, it became clear to the party hierarchy that younger leadership was needed. Gorbachev

was elected General Secretary by the Politburo on 11 March 1985, only

three hours after Chernenko's death. Upon his accession at age 54, he

was the youngest member of the Politburo. Mikhail Gorbachev was the Party's first leader to have been born after the Revolution. As de facto ruler of the USSR, he tried to reform the stagnating Party and the state economy by introducing glasnost ("openness"), perestroika ("restructuring"), demokratizatsiya ("democratization"), and uskoreniye ("acceleration" of economic development), which were launched at the 27th Congress of the CPSU in February 1986. Gorbachev's primary goal as General Secretary was to revive the Soviet economy after the stagnant Brezhnev years. In

1985, he announced that the Soviet economy was stalled and that

reorganization was needed. Gorbachev

soon realised that fixing the Soviet economy would be nearly impossible

without reforming the political and social structure of the Communist

nation. Gorbachev also initiated the concept of gospriyomka ("approval") during his time as leader, which represented state approval of goods in an effort to maintain quality control and combat inferior manufacturing. He made a speech in May 1985 in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) advocating widespread reforms. The reforms began in personnel changes; the most notable change was the replacement of Andrei Gromyko as Minister of Foreign Affairs with Eduard Shevardnadze.

Gromyko, disparaged as "Mr Nyet" in the West, had served for 28 years

as Minister of Foreign Affairs and was considered an 'old thinker'. A

number of reformist ideas were discussed by Politburo members. One of

the first reforms Gorbachev introduced was the anti-alcohol campaign,

begun in May 1985, which was designed to fight widespread alcoholism in the Soviet Union. Domestic changes continued apace. In a bombshell speech during Armenian SSR's

Central Committee Plenum of the Communist Party the young First

Secretary of Armenia's Hrazdan Regional Communist Party, Hayk

Kotanjian, criticised rampant corruption in the Armenian Communist

Party's highest echelons, implicating Armenian SSR Communist Party

First Secretary Karen Demirchyan and calling for his resignation. Symbolically, intellectual Andrei Sakharov was invited to return to Moscow by Gorbachev in December 1986 after six years of internal exile in Gorky.

During the same month, however, signs of the nationalities problem that

would haunt the later years of the Soviet Union surfaced as riots, named Jeltoqsan, occurred in Kazakhstan after Dinmukhamed Kunayev was replaced as First Secretary of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan. The Central Committee Plenum

in January 1987 would see the crystallisation of Gorbachev's political

reforms, including proposals for multi-candidate elections and the

appointment of non-Party members to government positions. He also first

raised the idea of expanding co-operatives at the plenum. Economic

reforms took up much of the rest of 1987, as a new law giving

enterprises more independence was passed in June and Gorbachev released

a book, Perestroika: New Thinking for Our Country and the World, in November, elucidating his main ideas for reform. 1988 would see Gorbachev's introduction of glasnost,

which gave new freedoms to the people, including greater freedom of

speech. At the same time, he opened himself and his reforms up for more

public criticism, evident in Nina Andreyeva's critical letter in a March edition of Sovetskaya Rossiya. The Law on Cooperatives enacted

in May 1988 was perhaps the most radical of the economic reforms during

the early part of the Gorbachev era. For the first time since Vladimir Lenin's New Economic Policy, the law permitted private ownership of businesses in the service, manufacturing, and foreign-trade sectors. In

June 1988, at the CPSU's Party Conference, Gorbachev launched radical

reforms meant to reduce party control of the government apparatus. He

proposed a new executive in the form of a presidential system, as well

as a new legislative element, to be called the Congress of People's Deputies. Elections

to the Congress of People's Deputies were held throughout the Soviet

Union in March and April 1989. This was the first free election in the

Soviet Union since 1917. Gorbachev became Chairman of the Supreme Soviet (or head of state) on 25 May 1989. On 15 March 1990, Gorbachev was elected as the first executive President of the Soviet Union with

59% of the Deputies' votes being an unopposed candidate. The Congress

met for the first time on 25 May in order to elect representatives from

Congress to sit on the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Boris Yeltsin was elected in Moscow and returned to political prominence to become an increasingly vocal critic of Gorbachev. In

contrast to his controversial domestic reforms, Gorbachev was largely

hailed in the West for his 'New Thinking' in foreign affairs. During

his tenure, he sought to improve relations and trade with the West by

reducing Cold War tensions. He established close relationships with

several Western leaders, such as West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, U.S. President Ronald Reagan, and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Gorbachev understood the link between achieving international

détente and domestic reform and thus began extending 'New

Thinking' abroad immediately. On 8 April 1985, he announced the

suspension of the deployment of SS-20s in

Europe as a move towards resolving intermediate-range nuclear weapons

(INF) issues. Later that year, in September, Gorbachev proposed that

the Soviets and Americans both cut their nuclear arsenals in half. He

went to France on his first trip abroad as Soviet leader in October.

November saw the Geneva Summit between Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan.

Though no concrete agreement was made, Gorbachev and Reagan struck a

personal relationship and decided to hold further meetings.

January 1986 would see Gorbachev make his boldest international move so

far, when he announced his proposal for the elimination of

intermediate-range nuclear weapons in

Europe and his strategy for eliminating all nuclear weapons by the year

2000 (often referred to as the 'January Proposal'). He also began the

process of withdrawing troops from Afghanistan and Mongolia on 28 July. On 11 October 1986, Gorbachev and Reagan met in Reykjavík, Iceland to

discuss reducing intermediate-range nuclear weapons in Europe. To the

immense surprise of both men's advisers, the two agreed in principle to

removing INF systems from Europe and to equal global limits of 100 INF

missile warheads. They also essentially agreed in principle to

eliminate all nuclear weapons in 10 years (by 1996), instead of by the

year 2000 as in Gorbachev's original outline.

In February, 1988, Gorbachev announced the full withdrawal of Soviet

forces from Afghanistan. The withdrawal was completed the following

year, although the civil war continued as the Mujahedin pushed to overthrow the pro-Soviet Najibullah government. An estimated 28,000 Soviets were killed between 1979 and 1989 as a result of the Afghanistan War. Also during 1988, Gorbachev announced that the Soviet Union would abandon the Brezhnev Doctrine, and allow the Eastern bloc nations

to freely determine their own internal affairs. Moscow's abandonment of

the Brezhnev Doctrine led to a string of counter-revolutions in Eastern Europe throughout 1989, in which Communism was overthrown. The loosening of Soviet hegemony over Eastern Europe effectively ended the Cold War, and for this, Gorbachev was awarded the Otto Hahn Peace Medal in Gold in 1989 and the Nobel Peace Prize on 15 October 1990. While Gorbachev's political initiatives were positive for freedom and democracy in the Soviet Union and its Eastern bloc allies,

the economic policy of his government gradually brought the country

close to disaster. By the end of the 1980s, severe shortages of basic

food supplies (meat, sugar)

led to the reintroduction of the war-time system of distribution using

food cards that limited each citizen to a certain amount of product per

month. Compared to 1985, the state deficit grew from 0 to 109 billion

rubles; gold funds decreased from 2,000 to 200 tons; and external debt

grew from 0 to 120 billion dollars. Furthermore, the democratisation of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe had irreparably undermined the power of the CPSU and

Gorbachev himself. The relaxation of censorship and attempts to create

more political openness had the unintended effect of re-awakening

long-suppressed nationalist and anti-Russian feelings in the Soviet republics. Calls for greater independence from Moscow's rule grew louder, especially in the Baltic republics of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia which had been annexed into the Soviet Union by Stalin in 1940. Nationalist feeling also took hold in Georgia, Ukraine, Armenia and Azerbaijan.

In December 1986, the first signs of the nationalities problem that

would haunt the later years of the Soviet Union's existence surfaced as

riots, named Jeltoqsan, occurred in Alma Ata and other areas of Kazakhstan after Dinmukhamed Kunayev was replaced as First Secretary of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan. Nationalism would then surface in Russia in May 1987, as 600 members of Pamyat, a nascent Russian nationalist group, demonstrated in Moscow and were becoming increasingly linked to Boris Yeltsin, who received their representatives at a meeting. Violence erupted in Nagorno-Karabakh - an Armenian-populated enclave within Azerbaijan -

between February and April, when Armenians living in the area began a

new wave of protests over the arbitrary transfer of the historically

Armenian region from Armenia

to Azerbaijan in 1920 upon Joseph Stalin's decision. Turmoil would once

again return in late 1988, this time in Armenia itself, when the Leninakan Earthquake hit the region on 7 December. Poor local infrastructure magnified the hazard and some 25,000 people died. In March and April 1989 elections to the Congress of People's Deputies took place throughout the Soviet Union. This returned many pro-independence republicans, as many CPSU candidates were rejected. The televised Congress debates

allowed the dissemination of pro-independence propositions. Indeed,

1989 would see numerous nationalistic expressions protests. Initiated

by the Baltic republics in January, laws were passed in most

non-Russian republics giving precedence for the republican language

over Russian. 9 April would see the crackdown of nationalist demonstrations by Soviet troops in Tbilisi. There would be further bloody protests in Uzbekistan in

June, where Uzbeks and Meskhetian Turks clashed in Fergana. Apart from

this violence, three major events that altered the face of the

nationalities issue occurred in 1989. Estonia had declared its

sovereignty in November, 1988, to be followed by Lithuania in May 1989

and by Latvia in July (the Communist Party of Lithuania would also declare its independence from the CPSU in December). This brought the Union and the republics into clear confrontation and would form a precedent for other republics. Finally, the Eastern bloc collapsed

in the autumn of 1989, raising hopes that Gorbachev would extend his

non-interventionist doctrine to the internal workings of the USSR. 1990 began with nationalist turmoil in January. Azerbaijanis rioted and troops were sent in to restore order; many Moldavians demonstrated in favour of unification with the post-Communist Romania; and Lithuanian demonstrations continued. The same month, in a hugely significant move, Armenia asserted

its right to veto laws coming from the All-Union level, thus

intensifying the 'war of laws' between republics and Moscow. Soon after, the CPSU,

which had already lost much of its control, began to lose even more

power as Gorbachev deepened political reform. The February Central

Committee Plenum advocated multi-party elections; local elections held

between February and March returned a large number of pro-independence

candidates. The Congress of People's Deputies then

amended the Soviet Constitution in March, removing Article 6, which

guaranteed the monopoly of the CPSU. The process of political reform

was therefore coming from above and below, and was gaining a momentum

that would augment republican nationalism. Soon after the

constitutional amendment, Lithuania declared independence and elected Vytautas Landsbergis as President. On 15 March, Gorbachev himself was elected as the only President of the Soviet Union by the Congress of People's Deputies and chose a Presidential Council of

15 politicians. Gorbachev was essentially creating his own political

support base independent of CPSU conservatives and radical reformers.

The new Executive was designed to be a powerful position to guide the

spiraling reform process, and the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union and

Congress of People's Deputies had already given Gorbachev increasingly

presidential powers in February. This would be again a source of

criticism from reformers. Boris Yeltsin was reaching a new level of

prominence, as he was elected Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR in May, effectively making him the de jure leader of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.

Problems for Gorbachev would once more come from the Russian parliament

in June, when it declared the precedence of Russian laws over All-Union

level legislation. Gorbachev's

personal position continued changing. At XXVIIIth CPSU Congress in

July, Gorbachev was re-elected General Secretary but this position was

now completely independent of Soviet government, and the Politburo had

no say in the ruling of the country. Gorbachev further reduced Party

power in the same month, when he issued a decree abolishing Party

control of all areas of the media and broadcasting. At the same time,

Gorbachev was working to consolidate his Presidential position,

culminating in the Supreme Soviet granting him special powers to rule

by decree in September in order to pass a much-needed plan for

transition to a market economy. However, the Supreme Soviet could not

agree on which programme to adopt. Gorbachev pressed on with political

reform, his proposal for setting up a new Soviet government, with a

Soviet of the Federation consisting of representatives from all 15

republics, was passed through the Supreme Soviet in November. In

December, Gorbachev was once more granted increased executive power by

the Supreme Soviet, arguing that such moves were necessary to counter

"the dark forces of nationalism". Such moves led to Eduard Shevardnadze's resignation;

Gorbachev's former ally warned of an impending dictatorship. This move

was a serious blow to Gorbachev personally and to his efforts for

reform. Meanwhile, Gorbachev was losing further ground to nationalists. October 1990 saw the founding of DemoRossiya, the Russian nationalist party; a few days later, both Ukraine and

Russia declared their laws completely sovereign over Soviet level laws.

The 'war of laws' had become an open battle, with the Supreme Soviet

refusing to recognise the actions of the two republics. Gorbachev would

publish the draft of a new union treaty in November, which envisioned a

continued union called the Union of Sovereign Soviet Republics, but, going into 1991, the actions of Gorbachev were steadily being overtaken by the centrifugal secessionist forces. January and February would see a new level of turmoil in the Baltic republics. On 10 January 1991 Gorbachev issued an ultimatum-like request addressing the Lithuanian Supreme Council demanding

the restoration of the validity of the constitution of the Soviet Union

in Lithuania and the revoking of all anti-constitutional laws. As a

result of continued violence, at least 14 civilians were killed and

more than 600 injured from 11-13 January 1991 in Vilnius,

Lithuania. The strong Western reaction and the actions of Russian

democratic forces put the president and government of the Soviet Union

into an awkward situation, as news of support for Lithuanians from

Western democracies started to appear. Further problems surfaced in Riga,

Latvia, on 20 January and 21, where OMON (special Ministry of the

Interior) troops killed 4 people. Archie Brown suggests that

Gorbachev's response this time was better, condemning the rogue action,

sending his condolences and suggesting that secession could take place

if it went through the procedures outlined in the Soviet constitution. Gorbachev

thus continued to draw up a new treaty of union which would have

created a truly voluntary federation in an increasingly democratised

Soviet Union. The new treaty was strongly supported by the Central Asian republics,

who needed the economic power and markets of the Soviet Union to

prosper. However, the more radical reformists, such as Russian SFSR President Boris Yeltsin,

were increasingly convinced that a rapid transition to a market economy

was required and were more than happy to contemplate the disintegration

of the Soviet Union if that was required to achieve their aims. On 12 June 1991 Boris Yeltsin was elected President of the Russian Federation by 57.3% of the vote (with a turnout of 74%). Hardliners in the Soviet leadership, calling themselves the 'State Emergency Committee', launched the August coup in

1991 in an attempt to remove Gorbachev from power and prevent the

signing of the new union treaty. During this time, Gorbachev spent

three days (19, 20 and 21 August) under house arrest at a dacha in the Crimea before

being freed and restored to power. However, upon his return, Gorbachev

found that neither union nor Russian power structures heeded his

commands as support had swung over to Yeltsin, whose defiance had led

to the coup's collapse. Between 21 August and 22 September, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan declared their intention to leave the Soviet Union. Simultaneously, Boris Yeltsin ordered the CPSU to suspend its activities on the territory of Russia and closed the Central Committee building at Staraya Ploschad. The Russian flag now flew beside the Soviet flag at the Kremlin.

In light of these circumstances, Gorbachev resigned as General

Secretary of the CPSU on 24 August and advised the Central Committee to

dissolve. Gorbachev's hopes of a new Union were further hit when the Congress of People's Deputies dissolved itself on 5 September. Though Gorbachev and the representatives of 8 republics (excluding Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia) signed an agreement on forming a new economic community on 18 October, events were overtaking Gorbachev.

With the country in a rapid state of deterioration, the final blow to

Gorbachev's vision was effectively dealt by a Ukrainian referendum on 1

December, where the Ukrainian people voted for independence. The

presidents of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus met in Belovezh Forest, near Brest, Belarus, on 8 December, founding the Commonwealth of Independent States and declaring the end of the Soviet Union in the Belavezha Accords. Gorbachev was presented with a fait accompli and reluctantly agreed with Yeltsin, on 17 December, to dissolve the Soviet Union. Gorbachev resigned on 25 December and the Soviet Union was

formally dissolved the next day.The Soviet Union was offically

dissolved the following day on December 26, 1991. Two days after

Gorbachev left office, on 27 December, Yeltsin moved into Gorbachev's old office. Following

his resignation and the collapse of the Soviet Union, Gorbachev

remained active in Russian politics. Especially during the early years

of the post-Soviet era, he expressed criticism at the reforms carried

out by Russian president Boris Yeltsin.

When president Yeltsin called a referendum for 25 April 1993 in an

attempt to achieve even greater powers as president, Gorbachev did not

vote, and instead called for new presidential elections to happen soon. Following a failed run for the presidency in 1996, Gorbachev established the Social Democratic Party of Russia, a union between several Russian social democratic parties.

He resigned as party leader in May 2004 over a disagreement with the

party's chairman over the direction taken in the December 2003 election

campaign. The party was later banned in 2007 by the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation due

to its failure to establish local offices with at least 500 members in

the majority of Russian regions, which is required by Russian law for a

political organisation to be listed as party. Later that year, Gorbachev founded a new political party, called the Union of Social-Democrats. In June 2004, Gorbachev represented Russia at the funeral of Ronald Reagan. Since his resignation, Gorbachev has remained involved in world affairs. He founded the Gorbachev Foundation in 1992, headquartered in San Francisco, California. He later founded Green Cross International, with which he was one of three major sponsors of the Earth Charter. He also became a member of the Club of Rome and the Club of Madrid. In the decade that followed the Cold War, Gorbachev opposed both the U.S.-led NATO bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999 and the U.S.-led Iraq War in 2003. Concerning the 2008 South Ossetia war, in a 12 August 2008 op-ed in The Washington Post, Gorbachev criticized the U.S. support for Georgian President Mikhail Saakashvili and for moving to bring Caucasus into the sphere of its "national interest." In September 2008 Gorbachev announced he would make a comeback to the Russian politics along with a former KGB officer,Alexander Lebedev. Their party is known as the Independent Democratic Party of Russia. He also is part owner of the opposition newspaper Novaya Gazeta. To commemorate the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Gorbachev accompanied former Polish leader Lech Walesa and German Chancellor Angela Merkel at a celebration in Berlinon 9 November 2009. Gorbachev

calls for a kind of perestroika or restructuring of societies around

the world, starting in particular with that of the United States,

because he is of the view that the economic crisis of 2007-present

shows that the Washington consensus economic model is a failure that will sooner or later have to be replaced. According to Gorbachev, countries such as Brazil, Malaysia and China which rejected the Washington consensus and the International Monetary Fund approach

to economic development, have done far better economically on the whole

and achieved far more fair results for the average citizen, than

countries that accepted it.