<Back to Index>

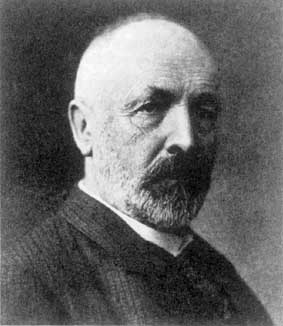

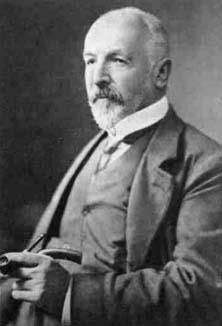

- Mathematician Georg Ferdinand Ludwig Phillip Cantor, 1845

- Photographer Arnold Abner Newman, 1918

- First President of the Swiss Confederation Jonas Furrer, 1805

Georg Ferdinand Ludwig Phillip Cantor (March 3 [O.S. February 19] 1845 – January 6, 1918) was a German mathematician, born in Russia. He is best known as the creator of set theory, which has become a fundamental theory in mathematics. Cantor established the importance of one-to-one correspondence between sets, defined infinite and well-ordered sets, and proved that the real numbers are "more numerous" than the natural numbers. In fact, Cantor's theorem implies the existence of an "infinity of infinities". He defined the cardinal and ordinal numbers and their arithmetic. Cantor's work is of great philosophical interest, a fact of which he was well aware.

Cantor's theory of transfinite numbers was originally regarded as so counter-intuitive—even shocking—that it encountered resistance from mathematical contemporaries such as Leopold Kronecker and Henri Poincaré and later from Hermann Weyl and L. E. J. Brouwer, while Ludwig Wittgenstein raised philosophical objections. Some Christian theologians (particularly neo-Scholastics) saw Cantor's work as a challenge to the uniqueness of the absolute infinity in the nature of God, on one occasion equating the theory of transfinite numbers with pantheism. The objections to his work were occasionally fierce: Poincaré referred to Cantor's ideas as a "grave disease" infecting the discipline of mathematics, and Kronecker's public opposition and personal attacks included describing Cantor as a "scientific charlatan", a "renegade" and a "corrupter of youth." Writing decades after Cantor's death, Wittgenstein lamented that mathematics is "ridden through and through with the pernicious idioms of set theory," which he dismissed as "utter nonsense" that is "laughable" and "wrong". Cantor's recurring bouts of depression from 1884 to the end of his life were once blamed on the hostile attitude of many of his contemporaries, but these episodes can now be seen as probable manifestations of a bipolar disorder.

The harsh criticism has been matched by later accolades. In 1904, the Royal Society awarded Cantor its Sylvester Medal, the highest honor it can confer. Cantor believed his theory of transfinite numbers had been communicated to him by God. David Hilbert defended it from its critics by famously declaring: "No one shall expel us from the Paradise that Cantor has created."

Cantor was born in 1845 in the western merchant colony in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and brought up in the city until he was eleven. Georg, the eldest of six children, was an outstanding violinist, having inherited his parents' considerable musical and artistic talents. Cantor's father had been a member of the Saint Petersburg stock exchange; when he became ill, the family moved to Germany in 1856, first to Wiesbaden then to Frankfurt, seeking winters milder than those of Saint Petersburg. In 1860, Cantor graduated with distinction from the Realschule in Darmstadt; his exceptional skills in mathematics, trigonometry in particular, were noted. In 1862, Cantor entered the Federal Polytechnic Institute in Zürich, today the ETH Zurich. After receiving a substantial inheritance upon his father's death in 1863, Cantor shifted his studies to the University of Berlin, attending lectures by Leopold Kronecker, Karl Weierstrass and Ernst Kummer. He spent the summer of 1866 at the University of Göttingen, then and later a very important center for mathematical research. In 1867, Berlin granted him the PhD for a thesis on number theory, De aequationibus secundi gradus indeterminatis. After teaching briefly in a Berlin girls' school, Cantor took up a position at the University of Halle, where he spent his entire career. He was awarded the requisite habilitation for his thesis on number theory. In

1874, Cantor married Vally Guttmann. They had six children, the last

(Rudolph) born in 1886. Cantor was able to support a family despite

modest academic pay, thanks to his inheritance from his father. During

his honeymoon in the Harz mountains, Cantor spent much time in mathematical discussions with Richard Dedekind, whom he befriended two years earlier while on Swiss holiday. Cantor

was promoted to Extraordinary Professor in 1872 and made full Professor

in 1879. To attain the latter rank at the age of 34 was a notable

accomplishment, but Cantor desired a chair at

a more prestigious university, in particular at Berlin, then the

leading German university. However, his work encountered too much

opposition for that to be possible. Kronecker,

who headed mathematics at Berlin until his death in 1891, became

increasingly uncomfortable with the prospect of having Cantor as a

colleague, perceiving him as a "corrupter of youth" for teaching his ideas to a younger generation of mathematicians. Worse

yet, Kronecker, a well-established figure within the mathematical

community and Cantor's former professor, fundamentally disagreed with

the thrust of Cantor's work. Kronecker, now seen as one of the founders

of the constructive viewpoint in mathematics,

disliked much of Cantor's set theory because it asserted the existence

of sets satisfying certain properties, without giving specific examples

of sets whose members did indeed satisfy those properties. Cantor came

to believe that Kronecker's stance would make it impossible for Cantor

to ever leave Halle. In 1881, Cantor's Halle colleague Eduard Heine died, creating a vacant chair. Halle accepted Cantor's suggestion that it be offered to Dedekind, Heinrich M. Weber and Franz Mertens,

in that order, but each declined the chair after being offered it.

Friedrich Wangerin was eventually appointed, but he was never close to

Cantor. In

1882, the mathematical correspondence between Cantor and Dedekind came

to an end, apparently as a result of Dedekind's refusal to accept the

chair at Halle. Cantor also began another important correspondence, with Gösta Mittag-Leffler in Sweden, and soon began to publish in Mittag-Leffler's journal Acta Mathematica. But in 1885, Mittag-Leffler was concerned about the philosophical

nature and new terminology in a paper Cantor had submitted to Acta. He asked Cantor to withdraw the paper from Acta while

it was in proof, writing that it was "... about one hundred years

too soon." Cantor complied, but wrote to a third party: "Had

Mittag-Leffler had his way, I should have to wait until the year 1984,

which to me seemed too great a demand! ... But of course I never want

to know anything again about Acta Mathematica." Cantor

then sharply curtailed his relationship and correspondence with

Mittag-Leffler, displaying a tendency to interpret well-intentioned

criticism as a deeply personal affront. Cantor suffered his first known bout of depression in 1884. Criticism

of his work weighed on his mind: every one of the fifty-two letters he

wrote to Mittag-Leffler in 1884 attacked Kronecker. This emotional crisis led him to apply to lecture on philosophy rather than mathematics. He also began an intense study of Elizabethan literature in an attempt to prove that Francis Bacon wrote the plays attributed to Shakespeare; this ultimately resulted in two pamphlets, published in 1896 and 1897. Cantor recovered soon thereafter, and subsequently made further important contributions, including his famous diagonal argument and theorem.

However, he never again attained the high level of his remarkable

papers of 1874–1884. He eventually sought a reconciliation with

Kronecker, which Kronecker graciously accepted. While

Cantor's mathematical worries and his difficulties dealing with certain

people were greatly magnified by his depression, it is doubtful that

they were its cause. Rather, his posthumous diagnosis of bipolarity has been accepted as the root cause of his erratic mood. In 1890, Cantor was instrumental in founding the Deutsche Mathematiker-Vereinigung and chaired its first meeting in Halle in 1891, where he first introduced his diagonal argument;

his reputation was strong enough, despite Kronecker's opposition to his

work, to ensure he was elected as the first president of this society.

Setting aside the animosity he felt towards Kronecker, Cantor invited

him to address the meeting, but Kronecker was unable to do so because

his spouse was dying from a skiing accident at the time. After Cantor's 1884 hospitalization, there is no record that he was in any sanatorium again until 1899. Soon

after that second hospitalization, Cantor's youngest son Rudolph died

suddenly (while Cantor was delivering a lecture on his views on Baconian theory and William Shakespeare), and this tragedy drained Cantor of much of his passion for mathematics. Cantor was again hospitalized in 1903. One year later, he was outraged and agitated by a paper presented by Julius König at the Third International Congress of Mathematicians.

The paper attempted to prove that the basic tenets of transfinite set

theory were false. Since it had been read in front of his daughters and

colleagues, Cantor perceived himself as having been publicly humiliated. Although Ernst Zermelo

demonstrated less than a day later that König's proof had failed,

Cantor remained shaken, even momentarily questioning God. Cantor

suffered from chronic depression for the rest of his life, for which he

was excused from teaching on several occasions and repeatedly confined

in various sanatoria. The events of 1904 preceded a series of

hospitalizations at intervals of two or three years. He did not abandon

mathematics completely, however, lecturing on the paradoxes of set

theory (Burali-Forti paradox, Cantor's paradox, and Russell's paradox) to a meeting of the Deutsche Mathematiker–Vereinigung in 1903, and attending the International Congress of Mathematicians at Heidelberg in 1904. In 1911, Cantor was one of the distinguished foreign scholars invited to attend the 500th anniversary of the founding of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. Cantor attended, hoping to meet Bertrand Russell, whose newly published Principia Mathematica repeatedly cited Cantor's work, but this did not come about. The following year, St. Andrews awarded Cantor an honorary doctorate, but illness precluded his receiving the degree in person. Cantor retired in 1913, and suffered from poverty, even malnourishment, during World War I. The

public celebration of his 70th birthday was canceled because of the

war. He died on January 6, 1918 in the sanatorium where he had spent

the final year of his life.