<Back to Index>

- Engineer Rudolf Christian Karl Diesel, 1858

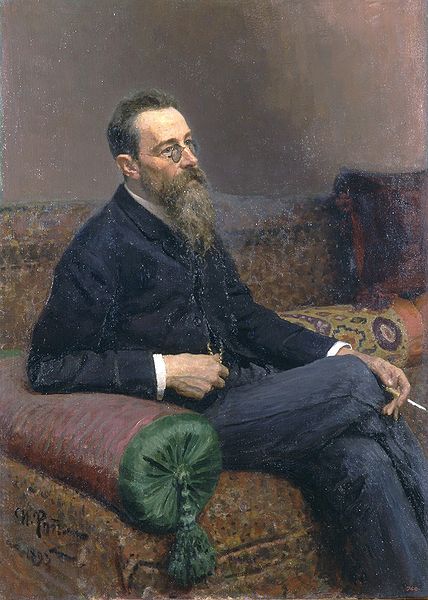

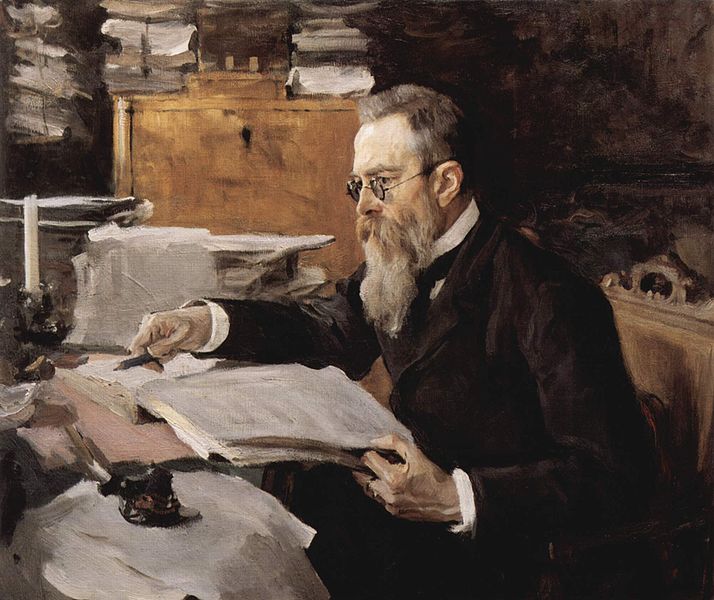

- Composer Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov, 1844

- King of Denmark and Norway Frederick III, 1609

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov (Russian: Николай Андреевич Римский-Корсаков; 18 March [O.S. 6 March] 1844 – 21 June [O.S. 8 June] 1908) was a Russian composer, and a member of the group of composers known as The Five. He was noted for folk and fairy-tale subjects as well as his skill in orchestration. His best-known orchestral compositions — Capriccio Espagnol, the Russian Easter Festival Overture, and the symphonic suite Scheherazade — are considered staples of the classical music repertoire, along with suites and excerpts from some of his 15 operas.

Rimsky-Korsakov initially believed, as did fellow composer Mily Balakirev and critic Vladimir Stasov, in developing a nationalistic style

of classical music. However, he came to

appreciate Western musical techniques after he became a professor of

musical composition, harmony and orchestration at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory in

1871. For

much of his life, Rimsky-Korsakov combined his compositional and

educational careers with one in the Russian military — at first as an

officer in the Imperial Russian Navy,

then in the civilian rank of Inspector of Naval Bands. Rimsky-Korsakov

is now considered "the main architect" of what the

classical music public considers the Russian style of composition.

While Rimsky-Korsakov's style was based on those of Mikhail Glinka,

Balakirev, Hector Berlioz and Franz Liszt, he "transmitted this style directly to two generations of Russian composers" and influenced non-Russian composers such as Maurice Ravel, Claude Debussy, Paul Dukas and Ottorino Respighi.

Rimsky-Korsakov was born at Tikhvin, 200 kilometres east of Saint Petersburg, into an aristocratic family with a long line of military and naval service. He

showed musical ability early; beginning at six, he took piano lessons

from various local teachers and showed a talent for aural skills. Although

he started composing his own compositions by age 10, he preferred

literature over music. From his reading as well as the exploits of his

brother Voin,

a naval officer 22 years Rimsky-Korsakov's senior who became noted as a

navigator and explorer, he developed a poetic love for the sea "without

ever having seen it". It

was this passion for the ocean, along with some prompting from Voin,

that encouraged the 12-year-old Rimsky-Korsakov to join the Imperial Russian Navy. He

studied at the School for Mathematical and Navigational Sciences in

Saint Petersburg and, at 18, took his final examination in April 1862. While at school, Rimsky-Korsakov took piano lessons from a man named Ulikh. Rimsky-Korsakov

wrote that while he remained "indifferent" to lessons, a love for music

manifested, fostered by visits to the opera, and, later, orchestral

concerts. Meanwhile,

Ulikh saw that he had serious musical talent, and

recommended another teacher, Feodor A. Kanille (Théodore

Canillé). Beginning

in the autumn of 1859, Rimsky-Korsakov took lessons in piano and

composition from Kanille. Through Kanille, he was exposed to a great deal of new music, including that of Glinka and Robert Schumann. Despite

Rimsky-Korsakov's finally liking music lessons, Voin cancelled them

when Rimsky-Korsakov was 17, as he felt they no longer served a

practical need. Regardless, Kanille told Rimsky-Korsakov to continue coming every Sunday, not for formal lessons but to play duets and discuss music. Then, in November 1861, Kanille introduced the 18-year-old to Mily Balakirev. Balakirev in turn introduced him to César Cui, and Modest Mussorgsky. All three of these men were already known as composers, despite only being in their 20s.

Balakirev encouraged Rimsky-Korsakov to compose and taught him the rudiments when he was not at sea. Balakirev also prompted him to enrich himself in other areas. When he showed Balakirev the beginning of a symphony in E-flat minor that he had written, Balakirev insisted he continue his efforts on it despite having almost no formal musical training. By the time Rimsky-Korsakov sailed on a two-year-and-eight-month cruise aboard the clipper Almaz in late 1862, he had completed and orchestrated three movements of the symphony. Eventually,

however, the lack of outside musical stimuli dulled the young

midshipman's hunger to learn, and he wrote to Balakirev that after two

years at sea, he had neglected his musical lessons for months. Once

Rimsky-Korsakov returned to Saint Petersburg in May 1865, his onshore

duties consisted of a couple of hours of clerical duty each day. Even so, Rimsky-Korsakov recalled that his desire to compose "had been stifled ... I did not concern myself with music at all". At

Balakirev's suggestion, he wrote a trio to the scherzo of the E-flat

minor symphony, which it had lacked up to that point, and

reorchestrated the entire symphony. The first performance of the symphony came in December of that year under Balakirev's direction in Saint Petersburg. The second performance followed in March 1866 under the direction of Konstantin Lyadov (father of composer Anatoly Lyadov). From

the correspondence between Rimsky-Korsakov and Balakirev, it is clear

that some of the ideas for the symphony originated with Balakirev. This

was typical of Balakirev, who seldom stopped at merely correcting a

piece of music, and would often recompose it at the piano. Though Rimsky-Korsakov would eventually find Balakirev's influence stifling and break free from it, this did not stop him in his memoirs from extolling the older composer's talents as a critic and improviser. Under

Balakirev's mentoring, Rimsky-Korsakov composed more works. He began a

symphony in B minor, but felt it too closely modeled on Beethoven's Ninth Symphony and abandoned it. He completed an Overture on Three Russian Themes, based on Balakirev's folksong overtures, as well as a Fantasia on Serbian Themes that was performed at a concert given for the delegates of the Slavonic Congress in 1867. In his review of this concert, nationalist critic Vladimir Stasov coined the phrase Moguchaya kuchka for the Balakirev circle (Moguchaya kuchka is usually translated as "The Mighty Handful" or "The Five"). Rimsky-Korsakov also composed the initial versions of Sadko and Antar, which would cement his reputation as a writer of orchestral works. Along

with composing, Rimsky-Korsakov spent time discussing music and

socializing with the other members of The Five; they critiqued one

another's works in progress and sometimes collaborated on new pieces. Rimsky-Korsakov

became especially noted within The Five and among those who visited the

circle for his talents as an orchestrator. He was asked by Balakirev to orchestrate a Schubert march for a concert in May 1868, by Cui to orchestrate the opening chorus of his opera William Ratcliff and by Alexander Dargomyzhsky, whose works were greatly appreciated by the Five and who was close to death, to orchestrate his opera The Stone Guest. In

the fall of 1871, Rimsky-Korsakov moved into Voin's former apartment,

and invited Mussorgsky to be his roommate. That

autumn Mussorgsky composed and orchestrated the Polish act of Boris Godunov and the folk scene 'Near Kromy' and Rimsky-Korsakov orchestrated and finished the Maid of Pskov. In

1871, the 27-year-old Rimsky-Korsakov became Professor of Practical

Composition and Instrumentation (orchestration) at the Saint Petersburg

Conservatory, as well as leader of the Orchestra Class. Even

while a professor at the Conservatory, he remained in active service as

a naval officer and taught his classes in uniform. To

prepare himself for his teaching role, and in an attempt to stay at

least one step ahead of his students, he took a three-year sabbatical

from composing original works, and assiduously studied at home while he

lectured at the Conservatory; he taught himself from textbooks and followed a strict regimen of composing contrapuntal exercises, fugues, chorales and a cappella choruses. Since he was assigned to rehearse the Orchestra Class, he was

compelled to master the art of conducting. The score of his Third Symphony,

written just after he had completed his three-year program of

self-improvement, reflects his hands-on experience with the orchestra. With Rimsky-Korsakov's professorship came financial security, which encouraged him to settle down and to start a family. In December 1871 he proposed to Nadezhda Purgold, and they married in July 1872, with Mussorgsky as Rimsky-Korsakov's best man. The Rimsky-Korsakovs would eventually have six children. One of their sons, Andrei, would become a musicologist, marry the composer Yuliya Veysberg and write a multi-volume study of his father's life and work. Nadezhda was to become a musical as well as domestic partner with her husband, much as Clara Schumann had been with her own husband Robert. She was beautiful, capable, strong-willed and far better trained musically than her husband at the time they married. Nadezhda

proved a fine and most demanding critic of her husband's work.

She travelled with her husband, attended rehearsals and arranged

compositions by him and others" for piano four hands, which she played with her husband. "Her

last years were dedicated to issuing her husband's posthumous literary

and musical legacy, maintaining standards for performance of his works

... and preparing material for a museum in his name." In

the spring of 1873, the navy created the post of Inspector of Naval

Bands and appointed Rimsky-Korsakov to this post; this allowed him to

resign his commission. As

Inspector, he visited naval bands throughout Russia, supervised the

bandmasters and their appointments, reviewed the bands' repertoire, and

inspected the quality of their instruments. He also wrote a study

program for a complement of music students who held navy fellowships at

the Conservatory, and acted as an intermediary between the Conservatory

and the navy. The post of Band Inspector came with a promotion to

Collegiate Assessor, a civilian rank. In

March 1884, an Imperial Order abolished the navy office of Inspector of

Bands, and Rimsky-Korsakov was relieved of his duties. He worked under Balakirev in the Court Chapel as a deputy until 1894, which allowed him to study Russian Orthodox church music. Two

projects helped Rimsky-Korsakov focus on less academic music-making.

The first was the creation of two folk song collections in 1874.

Approached at Balakirev's suggestion by folk singer Tvorty Filipov, Rimsky-Korsakov transcribed 40 Russian songs for voice and piano from performances by Filippov. This

collection was followed by a second of 100 songs, many supplied by

friends and servants, and others taken from rare and out-of-print

collections. The

second project was the editing of orchestral scores by pioneer Russian

composer Mikhail Glinka (1804–1857) in collaboration with Balakirev and Anatoly Lyadov. This

project was prompted by Glinka's sister, Lyudmila Ivanovna Shestakova,

who wanted to preserve her brother's musical legacy in print, and paid

the costs of the project from her own pocket. In the summer of 1877, Rimsky-Korsakov thought increasingly about the short story "May Night" by Nikolai Gogol.

The story had long been a favorite of his, and his wife Nadezhda had

encouraged him to write an opera based on it from the day of their

betrothal, when they had read it together. While some musical ideas for such a work predated 1877, now they came with even greater persistence. By winter May Night took

an increasing amount of his attention; in February 1878 he started

writing in earnest, and he finished the opera by early November. Despite the ease at which he wrote this opera and the rapidity at which he penned the next, The Snow Maiden, from time to time he suffered from creative paralysis between 1881 and 1888. He kept busy during this time by editing Mussorgsky's works and completing Borodin's Prince Igor (Mussorgsky died in 1881, Borodin in 1887). Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that he became acquainted with budding music patron Mitrofan Belyayev in Moscow in 1882. By

the winter of 1883 Rimsky-Korsakov had become a regular visitor to the

weekly "quartet Fridays" ("Les Vendredis") held at Belyayev's home in

Saint Petersburg. Rimsky-Korsakov came up with the

idea of offering several concerts per year featuring Russian

compositions, a prospect to which Belyayev was amenable. The Russian Symphony Concerts were inaugurated during the 1886–87 season, with Rimsky-Korsakov sharing conducting duties. The concerts coaxed him out of his creative drought; he wrote Scheherazade, Capriccio Espagnol and the Russian Easter Overture specifically for them. Rimsky-Korsakov

was asked for advice and guidance not just on the Russian Symphony

Concerts, but on several other projects through which Belyayev aided

Russian composers. The group of composers who now congregated with Glazunov, Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov became known as the Belyayev circle,

named after their financial benefactor. These composers were

nationalistic in their musical outlook, as The Five before them had

been. Like The Five, they believed in a uniquely Russian style of

classical music that utilized folk music and exotic melodic, harmonic

and rhythmic elements, as exemplified by the music of Balakirev,

Borodin and Rimsky-Korsakov. Unlike The Five, these composers also

believed in the necessity of an academic, Western-based background in

composition—something that Rimsky-Korsakov had instilled into many of

them in his years at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. In

November 1887, Tchaikovsky arrived in Saint Petersburg in time to hear

several of the Russian Symphony Concerts. One of these concerts

included the first complete performance of his First Symphony, subtitled Winter Daydreams, in its final version. Another concert featured the premiere of Rimsky-Korsakov's Third Symphony in its revised version. Before

this visit, Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky had corresponded

considerably, and during the visit, the two men spent much time

together, along with Glazunov and Lyadov. Though Tchaikovsky had been a regular visitor to the Rimsky-Korsakov home since 1876, and had at one point offered to arrange Rimsky-Korsakov's appointment as director of the Moscow Conservatory, this

would be the beginning of closer relations between the pair. Within a

couple of years, Rimsky-Korsakov wrote, Tchaikovsky's visits became

more frequent. During

these visits and especially in public, Rimsky-Korsakov wore a mask of

geniality. Privately, he found the situation emotionally complex, and

confessed his fears to his friend, the Moscow critic Semyon Kruglikov. Rimsky-Korsakov

also observed, not without some annoyance, how Tchaikovsky became

increasingly popular among Rimsky-Korsakov's followers. The

personal jealousy Rimsky-Korsakov felt was compounded by a professional

one, as Tchaikovsky's music became increasingly popular among the

composers of the Belyayev circle, and remained overall more famous than

his own. Even

so, when Tchaikovsky attended Rimsky-Korsakov's nameday party in May

1893, Rimsky-Korsakov asked Tchaikovsky personally if he would conduct

four concerts of the Russian Musical Society in Saint Petersburg the following season. After some hesitation, Tchaikovsky agreed. While

his sudden death prevented him from fulfilling this commitment in its

entirety, the list of works he planned to conduct included

Rimsky-Korsakov's Third Symphony. What

would become the climactic event in Rimsky-Korsakov's creative life was

the visit to Saint Petersburg of Angelo Neumann's traveling "Richard Wagner Theater". This company gave four cycles of Der Ring des Nibelungen there under the direction of Karl Muck in March 1889. The Five had long ignored Wagner's music, but Rimsky-Korsakov was impressed when he heard the Ring. He

was astonished with Wagner's mastery of orchestration; he attended all

the rehearsals with Glazunov and followed along with the score. After

he had heard these performances, Rimsky-Korsakov devoted himself almost

exclusively to composing operas for the rest of his creative life.

Wagner's use of the orchestra also influenced Rimsky-Korsakov's orchestration, beginning with the arrangement of the polonaise from Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov that he made for concert use in 1889. In 1892 Rimsky-Korsakov suffered a second creative drought, brought

on by bouts of depression and alarming physical symptoms—rushes of

blood to the head, confusion, memory loss and unpleasant obsessions. The medical diagnosis was neurasthenia. Another

cause for the depression may have been several crises in the

Rimsky-Korsakov household—the serious illnesses of his wife and one of

his sons from diphtheria in

1890, the deaths of his mother and youngest child, as well as the onset

of the prolonged, ultimately fatal illness of his second youngest child. He resigned from the Russian Symphony Concerts and the Court Chapel and considered giving up composition permanently. After making third versions of the musical tableau Sadko and the opera The Maid of Pskov, he closed his musical account with the past; he had left none of his major works before May Night in their original form. Another death brought about a creative renewal. The

passing of Tchaikovsky in late 1893 presented a two-fold opportunity—to

write for the Imperial Theaters and to compose an opera based on Nikolai Gogol's short story "Christmas Eve", a work on which Tchaikovsky had based his opera Vakula the Smith. The success of this opera, Christmas Eve,

encouraged Rimsky-Korsakov to complete an opera approximately every 18

months between 1893 and 1908—a total of 11 during this period. He also started and abandoned another draft of his treatise on orchestration, but made a third attempt and almost finished it in the last four years of his life. (His son-in-law Maximilian Steinberg completed the book posthumously in 1912.)

Rimsky-Korsakov's scientific treatment of orchestration, illustrated

with more than 300 examples from his work, set a new standard for texts

of its kind. In 1905, demonstrations took place at Saint Petersburg Conservatory as part of the February Revolution; these, Rimsky-Korsakov wrote, were triggered by similar disturbances at Saint Petersburg State University, in which students demanded political reforms and establishment of a constitutional monarchy in Russia. In

an open letter, he sided with the students against what he saw as

unwarranted interference by Conservatory leadership and the Russian

Musical Society. A

second letter, this time signed by a number of faculty including

Rimsky-Korsakov, demanded the resignation of the head of the

Conservatory. Partly

as a result of these two letters, approximately 100

Conservatory students were expelled, and he was removed from his

professorship. Not long afterwards, a student production of his opera Kaschei the Immortal was followed not with the scheduled concert but with a political demonstration, which led to a police ban on Rimsky-Korsakov's work. Due in part to widespread press coverage of these events, an

immediate wave of outrage to the ban arose throughout Russia and

abroad; liberals and intellectuals deluged the composer's residence

with letters of sympathy, and even peasants who had not heard a note of Rimsky-Korsakov's music sent small monetary donations. Several faculty members of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory resigned in protest, including Glazunov and Lyadov. Eventually, over 300 students walked out of the Conservatory in solidarity with Rimsky-Korsakov. By December he had been reinstated under a new director, Glazunov, and would retire from the Conservatory in 1906. However, the political controversy continued with his opera The Golden Cockerel. Its implied criticism of monarchy, Russian imperialism and the Russo-Japanese War gave it little chance of passing the censors. The premiere was delayed until 1909, after Rimsky-Korsakov's death. Even then, it was performed in an adapted version. In April 1907, Rimsky-Korsakov conducted a pair of concerts in Paris, hosted by impressario Sergei Diaghilev,

which featured music of the Russian nationalist school. The concerts

were hugely successful in popularizing Russian classical music of this

kind, as well as in the fortunes of Rimsky-Korsakov's music in Europe. The following year, his opera Sadko was produced at the Paris Opéra and The Snow Maiden at the Opére Comique. He also had the opportunity to hear more recent music by European composers. Beginning around 1890, Rimsky-Korsakov suffered from angina. While

this ailment initially wore him down gradually, the stresses concurrent

with the February Revolution and its aftermath greatly accelerated its

progress. After December 1907, his illness became severe, and prevented

all work. He died in Lyubensk in 1908, and was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in Saint Petersburg, next to Borodin, Glinka, Mussorgsky and Stasov.