<Back to Index>

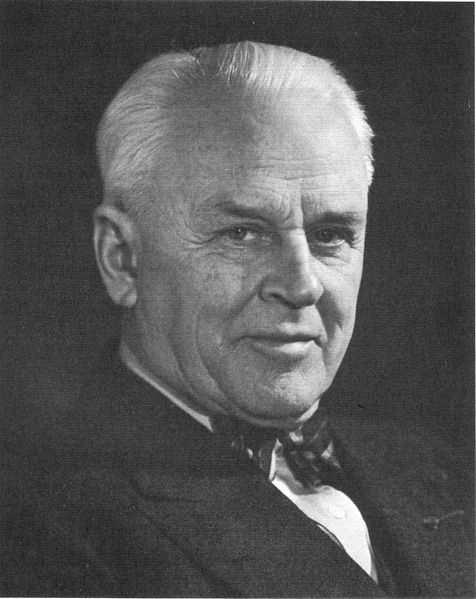

- Physicist Robert A. Millikan, 1868

- Painter Anthony van Dyck, 1599

- President of the Philippines Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy, 1869

Robert Andrews Millikan (22 March 1868 – 19 December 1953) was an American experimental physicist, and Nobel laureate in physics for his measurement of the charge on the electron and for his work on the photoelectric effect. He served as president of Caltech from 1921 to 1945.

Millikan went to high school in Maquoketa, Iowa. Millikan received a Bachelor's degree in the classics from Oberlin College in 1891 and his doctorate in physics from Columbia University in 1895 – he was the first to earn a Ph.D. from that department. He was the coauthor of a popular and influential series of introductory textbooks, which were ahead of their time in many ways. Compared to other books of the time, they treated the subject more in the way in which it was thought about by physicists.

In 1902 he married Greta Ervin Blanchard. They had three sons - Clark Blanchard, Glenn Allen, and Max Franklin. Starting in 1909, while a professor at the University of Chicago, Millikan and Harvey Fletcher worked on an oil-drop experiment in which they measured the charge on a single electron. Professor Millikan took sole credit, in return for Fletcher claiming full authorship on a related result for his dissertation. Millikan went on to win the 1923 Nobel Prize for Physics, in part for this work, and Fletcher kept the agreement a secret until his death. After a publication on his first results in 1910, contradictory observations by Felix Ehrenhaft started a controversy between the two physicists. After improving his setup he published his seminal study in 1913. The elementary charge is one of the fundamental physical constants and

accurate knowledge of its value is of great importance. His experiment

measured the force on tiny charged droplets of oil suspended against

gravity between two metal electrodes. Knowing the electric field, the

charge on the droplet could be determined. Repeating the experiment for

many droplets, Millikan showed that the results could be explained as integer multiples of a common value, the charge on a single electron. That this is somewhat lower than the modern value is probably due to Millikan's use of an inaccurate value for the viscosity of air. Although

at the time of Millikan's oil-drop experiments it was becoming clear

that there exist such things as subatomic particles, not everyone was

convinced. Experimenting with cathode rays in 1897, J.J. Thomson had discovered negatively charged 'corpuscles', as he called them, with a mass to charge ratio 1/1840 times that of a hydrogen ion. Similar results had been found by George Fitzgerald and Walter Kaufmann.

Most of what was then known about electricity and magnetism, however,

could be explained on the basis that charge is a continuous variable;

in much the same way that many of the properties of light can be

explained by treating it as a continuous wave rather than as a stream

of photons. When Einstein published

his seminal 1905 paper on the particle theory of light, Millikan was

convinced that it had to be wrong, because of the vast body of evidence

that had already shown that light was a wave.

He undertook a decade-long experimental program to test Einstein's

theory, which required building what he described as "a machine shop in vacuo"

in order to prepare the very clean metal surface of the photo

electrode. His results confirmed Einstein's predictions in every

detail, but Millikan was not convinced of Einstein's interpretation,

and as late as 1916 he wrote, "Einstein's photoelectric equation...

cannot in my judgment be looked upon at present as resting upon any

sort of a satisfactory theoretical foundation," even though "it

actually represents very accurately the behavior" of the photoelectric

effect. In his 1958 Book of discoveries on science experiments,

however, he simply declared that his work "scarcely permits of any

other interpretation than that which Einstein had originally suggested,

namely that of the semi-corpuscular or photon theory of light itself." Millikan is also credited

with measuring the value of Planck's constant by using photoelectric emission graphs of various metals. In 1917, solar astronomer George Ellery Hale convinced Millikan to begin spending several months each year at the Throop College of Technology, a small academic institution in Pasadena, California that

Hale wished to transform into a major center for scientific research

and education. A few years later Throop College became the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), and Millikan left the University of Chicago in

order to become Caltech's "chairman of the executive council"

(effectively its president). Millikan would serve in that position from

1921 to 1945. At Caltech most of his scientific research focused on the

study of "cosmic rays" (a term which he coined). In the 1930s he entered into a debate with Arthur Compton over

whether cosmic rays were composed of high-energy photons (Millikan's

view) or charged particles (Compton's view). Millikan thought his

cosmic ray photons were the "birth cries" of new atoms continually being created by God to counteract entropy and prevent the heat death of the universe. Compton would eventually be proven right by the observation that cosmic rays are deflected by the Earth's magnetic field (and so must be charged particles). Robert

Millikan was Vice Chairman of the National Research Council during

World War I. During that time, he helped to develop anti-submarine and

meteorological devices. He received the Chinese Order of Jade. In

his later life he became interested in the relationship between

Christian faith and science, his own father having been a minister. He

dealt with this in his Terry Lectures at Yale in 1926–7, published as Evolution in Science and Religion. A more controversial belief of his was eugenics. This led to his association with the Human Betterment Foundation and his praising of San Marino, California for

being "the westernmost outpost of Nordic civilization . . . [with] a

population which is twice as Anglo-Saxon as that existing in New York,

Chicago or any of the great cities of this country." Millikan died of a heart attack at his home in San Marino, California in 1953 at age 85, and was interred in the "Court of Honor" at Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Glendale, California.