<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Alexander Grothendieck, 1928

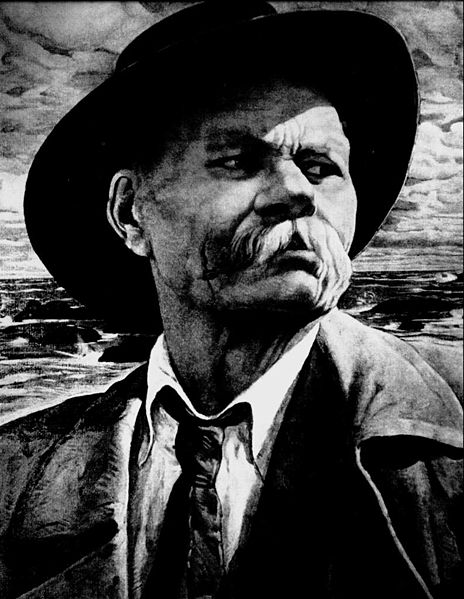

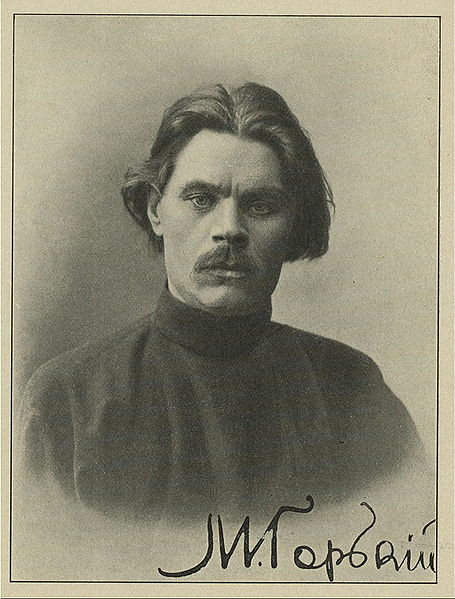

- Author Maxim Gorky, 1868

- Prime Minister of France Aristide Briand, 1862

Aleksey Maksimovich Peshkov (Russian: Алексе́й Макси́мович Пе́шков or Пешко́в) (28 March [O.S. 16 March] 1868 – 18 June 1936), better known as Maxim Gorky (Макси́м Го́рький), was a Russian/Soviet author, a founder of the socialist realism literary method and a political activist. From 1906 to 1913 and from 1921 to 1929 he lived abroad, mostly in Capri, Italy; after his return to the Soviet Union he accepted the cultural policies of the time, although he was not permitted to leave the country.

Gorky was born in Nizhny Novgorod and became an orphan at

the age of ten. Two years later at the age of 12 in 1880 he ran away

from home and was trying to find his grandmother. Gorky was brought up

by his grandmother, an excellent storyteller. Her death deeply affected him, and after an attempt at suicide in December 1887, he travelled on foot across the Russian Empire for five years, changing jobs and accumulating impressions used later in his writing. As a journalist working in provincial newspapers, he wrote under the pseudonym Иегудиил Хламида (Jehudiel Khlamida — suggestive of "cloak-and-dagger" by the similarity to the Greek chlamys, "cloak"). He began using the pseudonym Gorky (literally "bitter") in 1892, while working in the Tiflis newspaper Кавказ (The Caucasus). The name reflected his simmering anger about life in Russia and a determination to speak the bitter truth. Gorky's first book Очерки и рассказы (Essays and Stories)

in 1898 enjoyed a sensational success and his career as a writer began.

Gorky wrote incessantly, viewing literature less as an aesthetic

practice (though he worked hard on style and form) than as a moral and

political act that could change the world. He described the lives of

people in the lowest strata and on the margins of society, revealing

their hardships, humiliations, and brutalization, but also their inward

spark of humanity. Gorky’s

reputation as a unique literary voice from the bottom strata of society

and as a fervent advocate of Russia's social, political, and cultural

transformation (by 1899, he was openly associating with the emerging Marxist social-democratic movement)

helped make him a celebrity among both the intelligentsia and the

growing numbers of "conscious" workers. At the heart of all his work

was a belief in the inherent worth and potential of the human person (личность,

lichnost). He counterposed vital individuals, aware of their natural

dignity, and inspired by energy and will, to people who succumb to the

degrading conditions of life around them. Still, both his writings and

his letters reveal a "restless man" (a frequent self-description)

struggling to resolve contradictory feelings of faith and skepticism,

love of life and disgust at the vulgarity and pettiness of the human

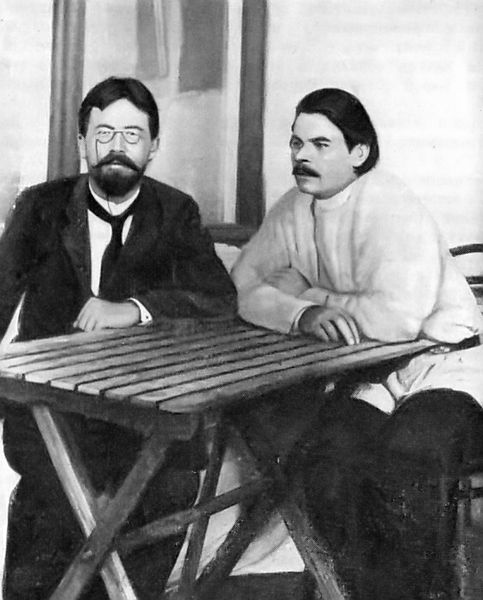

world. He publicly opposed the Tsarist regime and was arrested many times. Gorky befriended many revolutionaries and became Lenin's personal friend after they met in 1902. He exposed governmental control of the press. In 1902, Gorky was elected an honorary Academician of Literature, but Nicholas II ordered this annulled. In protest, Anton Chekhov and Vladimir Korolenko left the Academy. The

years 1900 to 1905 saw a growing optimism in Gorky’s writings. He

became more involved in the opposition movement, for which he was again

briefly imprisoned in 1901. In 1904, having severed his relationship

with the Moscow Art Theatre in the wake of conflict with Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, Gorky returned to Nizhny Novgorod to establish a theatre of his own. Both Constantin Stanislavski and Savva Morozov provided financial support for the venture. Stanislavski

saw in Gorky's theatre an opportunity to develop the network of

provincial theatres that he hoped would reform the art of the stage in

Russia, of which he had dreamed since the 1890s. He sent some pupils from the Art Theatre School—as well as Ioasaf Tikhomirov, who ran the school — to work there. By the autumn, however, after the censor had banned every play that the theatre proposed to stage, Gorky abandoned the project. Now a financially-successful author, editor, and playwright, Gorky gave financial support to the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP),

though he also supported liberal appeals to the government for civil

rights and social reform. The brutal shooting of workers marching to

the Tsar with a petition for reform on January 9, 1905 (known as the "Bloody Sunday"), which set in motion the Revolution of 1905, seems to have pushed Gorky more decisively toward radical solutions. He now became closely associated with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik wing

of the party—though it is not clear whether he ever formally joined and

his relations with Lenin and the Bolsheviks would always be rocky. His

most influential writings in these years were a series of political

plays, most famously The Lower Depths (1902). In 1906, the Bolsheviks sent him on a fund-raising trip to the United States, where in the Adirondack Mountains Gorky wrote his famous novel of revolutionary conversion and struggle, Мать (Mat’, The Mother). His experiences there—which included a scandal over his traveling with

his lover rather than his wife—deepened his contempt for the "bourgeois

soul" but also his admiration for the boldness of the American spirit.

While briefly imprisoned in Peter and Paul Fortress during the abortive 1905 Russian Revolution, Gorky wrote the play Children of the Sun, nominally set during an 1862 cholera epidemic, but universally understood to relate to present-day events. From 1906 to 1913, Gorky lived on the island of Capri, partly for health reasons and partly to escape the increasingly repressive atmosphere in Russia. He

continued to support the work of Russian social-democracy, especially

the Bolsheviks, and to write fiction and cultural essays. Most

controversially, he articulated, along with a few other maverick

Bolsheviks, a philosophy he called "God-Building", which

sought to recapture the power of myth for the revolution and to create

a religious atheism that placed collective humanity where God had been

and was imbued with passion, wonderment, moral certainty, and the

promise of deliverance from evil, suffering, and even death. Though

'God-Building' was suppressed by Lenin, Gorky retained his belief that

"culture" — the moral and spiritual awareness of the value and potential

of the human self — would be more critical to the revolution’s success

than political or economic arrangements. An amnesty granted for the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty

allowed Gorky to return to Russia in 1913, where he continued his

social criticism, mentored other writers from the common people, and

wrote a series of important cultural memoirs, including the first part

of his autobiography. On

returning to Russia, he wrote that his main impression was that

"everyone is so crushed and devoid of God's image." The only solution,

he repeatedly declared, was "culture". During World War I, his apartment in Petrograd was turned into a Bolshevik staff room, but his relations with the Communists turned sour. After his newspaper Novaya Zhizn (Новая Жизнь, "New Life") fell prey to Bolshevik censorship, Gorky published a collection of essays critical of the Bolsheviks called Untimely Thoughts in

1918. (It would not be published in Russia again until the end of the

Soviet Union.) The essays call Lenin a tyrant for his senseless arrests

and repression of free discourse, and an anarchist for his

conspiratorial tactics; Gorky compares Lenin to both the Tsar and Nechayev. In August 1921, Nikolai Gumilyov, his friend, fellow writer and Anna Akhmatova's husband, was arrested by the Petrograd Cheka for his monarchist views.

Gorky hurried to Moscow, obtained an order to release Gumilyov from

Lenin personally, but upon his return to Petrograd he found out that

Gumilyov had already been shot. In October, Gorky returned to Italy on health grounds: he had tuberculosis. According to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Gorky's return to the Soviet Union was motivated by material needs. In Sorrento, Gorky found himself without money and without fame. He visited the USSR several times after 1929, and in 1932 Joseph Stalin personally invited him to return for good, an offer he accepted. In June 1929, Gorky visited Solovki (cleaned up for this occasion) and wrote a positive article about that Gulag camp, which had already gained ill fame in the West.

Later he stated that everything he had written was under the control of

censors. Gorky's return from Fascist Italy was a major propaganda victory for the Soviets. He was decorated with the Order of Lenin and given a mansion (formerly belonging to the millionaire Ryabushinsky, now the Gorky Museum) in Moscow and a dacha in

the suburbs. One of the central Moscow streets, Tverskaya, was renamed

in his honor, as was the city of his birth. The largest fixed-wing

aircraft in the world in the mid-1930s, the Tupolev ANT-20, was also named Maxim Gorky. On October 11, 1931 Gorky read his fairy tale "A Girl and Death" to his visitors Joseph Stalin, Kliment Voroshilov and Vyacheslav Molotov,

an event that was later depicted by Viktor Govorov on his painting. In 1933 Gorky edited an infamous book about the White Sea-Baltic Canal, presented as an example of "successful rehabilitation of the former enemies of proletariat". With the increase of Stalinist repression and especially after the assassination of Sergei Kirov in December 1934, Gorky was placed under unannounced house arrest in his Moscow house. The

sudden death of his son Maxim Peshkov in May 1934 was followed by the

death of Maxim Gorky himself in June 1936. Speculation has long

surrounded the circumstances of his death. Stalin and Molotov were among those who carried Gorky's coffin during the funeral.