<Back to Index>

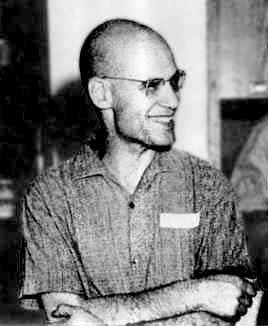

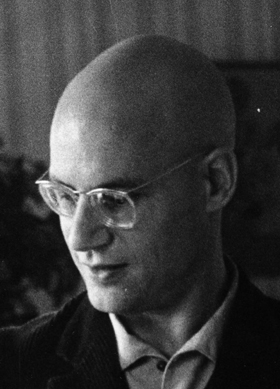

- Mathematician Alexander Grothendieck, 1928

- Author Maxim Gorky, 1868

- Prime Minister of France Aristide Briand, 1862

Alexander Grothendieck (born March 28, 1928 Berlin) is one of the most influential mathematicians of the twentieth century, known principally for his revolutionary advances in algebraic geometry, but also for major contributions to algebraic topology, number theory, category theory, Galois theory, descent theory, commutative homological algebra and functional analysis. He was awarded the Fields Medal in 1966, and was co-awarded the Crafoord Prize with Pierre Deligne in 1988, but Grothendieck declined it.

He

is noted for his mastery of abstract approaches to mathematics, and his

perfectionism in matters of formulation and presentation. In

particular, he demonstrated the ability to derive concrete results

using only very general methods. Relatively little of his work after

1960 was published by the conventional route of the learned journal,

circulating initially in duplicated volumes of seminar notes; his

influence was to a considerable extent personal, on French mathematics

and the Zariski school at Harvard University. He retired in 1988 and within a few years became reclusive. Alexander Grothendieck was born in Berlin to anarchist parents: a Russian father from an ultimately Hassidic family, Alexander "Sascha" Shapiro (aka Tanaroff), and a mother from a German Protestant family, Johanna "Hanka" Grothendieck; both of his parents had broken away from their early backgrounds in their teens. At

the time of his birth Grothendieck's mother was married to Johannes

Raddatz, a German journalist, and his birthname was initially recorded

as Alexander Raddatz. The marriage was dissolved in 1929 and Shapiro/Tanaroff acknowledged his paternity, but never married Hanka Grothendieck. Grothendieck lived with his parents until 1933 in Berlin. At the end of that year, Shapiro moved to Paris, and Hanka followed him the next year. They left Grothendieck in the care of Wilhelm Heydorn, a Lutheran Pastor and teacher in Hamburg where he went to school. During this time, his parents fought in the Spanish Civil War.

In 1939 Grothendieck came to France and lived in various camps for displaced persons with his mother, first at the Camp de Rieucros, and subsequently lived for the remainder of the war in the village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon,

where he, along with other Jewish children, was sheltered and hidden in

local boarding-houses or pensions. His father was sent via Drancy to Auschwitz where he died in 1942. While Grothendieck lived in Chambon, he attended the Collège Cévenol (now known as the Le Collège-Lycée Cévenol International),

a unique secondary school founded in 1938 by local Protestant pacifists

and anti-war activists. Many of the other Jewish refugee children being

hidden in Chambon attended Cévenol and it was at this school

that Grothendieck apparently first became fascinated with mathematics. After the war, the young Grothendieck studied mathematics in France, initially at the University of Montpellier.

He had decided to become a math teacher because he had been told that

mathematical research had been completed early in the 20th century and

there were no more open problems. However, his talent was noticed, and he was encouraged to go to Paris in 1948. Initially, Grothendieck attended Henri Cartan's Seminar at École Normale Supérieure, but lacking the necessary background to follow the high-powered seminar, he moved to the University of Nancy where he wrote his dissertation under Laurent Schwartz in functional analysis, from 1950 to 1953. At this time he was a leading expert in the theory of topological vector spaces. By 1957, he set this subject aside in order to work in algebraic geometry and homological algebra. Installed at the Institut des Hautes Études Scientifiques (IHÉS), Grothendieck attracted attention by an intense and highly productive activity of seminars (de facto working

groups drafting into foundational work some of the ablest French and

other mathematicians of the younger generation). Grothendieck himself

practically ceased publication of papers through the conventional, learned journal route. He was, however, able to play a dominant role in mathematics for around a decade, gathering a strong school. During this time he had officially as students Michel Demazure (who worked on SGA3, on group schemes), Luc Illusie (cotangent complex), Michel Raynaud, Jean-Louis Verdier (cofounder of the derived category theory) and Pierre Deligne. Collaborators on the SGA projects also included Mike Artin (étale cohomology) and Nick Katz (monodromy theory and Lefschetz pencils). Jean Giraud worked out torsor theory extensions of non-abelian cohomology. Many others were involved. Alexander Grothendieck's work during the `Golden Age' period at IHÉS established several unifying themes in algebraic geometry, number theory, topology, category theory and complex analysis. His first (pre-IHÉS) breakthrough in algebraic geometry was theGrothendieck–Hirzebruch–Riemann–Roch theorem, a far-reaching generalisation of the Hirzebruch–Riemann–Roch theorem proved algebraically; in this context he also introduced K-theory. Then, following the programme he outlined in his talk at the 1958 International Congress of Mathematicians, he introduced the theory of schemes, developing it in detail in his Éléments de géométrie algébrique (EGA)

and providing the new more flexible and general foundations for

algebraic geometry that has been adopted in the field since that time.

He went on to introduce the étale cohomology theory of schemes, providing the key tools for proving the Weil conjectures, as well as crystalline cohomology and algebraic de Rham cohomology to complement it. Closely linked to these cohomology theories, he originated topos theory

as a generalisation of topology. He also provided an algebraic definition of fundamental groups of schemes and more generally the main structures of a categorical Galois theory. As a framework for his coherent duality theory he also introduced derived categories, which were further developed by Verdier. The results of work on these and other topics were published in the EGA and in less polished form in the notes of the Séminaire de géométrie algébrique (SGA) that he directed at IHES. Grothendieck's political views were radical and pacifist. Thus, he strongly opposed both United States aggression in Vietnam as well as Soviet military expansionism. He gave lectures on category theory in the forests surrounding Hanoi while the city was being bombed, to protest against the Vietnam War. He retired from

scientific life around 1970, after having discovered the partly

military funding of IHÉS. He returned to

academia a few years later as a professor at the University of Montpellier,

where he stayed until his retirement in 1988. His criticisms of the

scientific community, and especially of several mathematics circles,

are also contained in a letter, written in 1988, in which he states the

reasons for his refusal of the Crafoord Prize. He declined the prize on ethical grounds in an open letter to the media. While

the issue of military funding was perhaps the most obvious explanation

for Grothendieck's departure from IHÉS, those who knew him say

that the causes of the rupture ran deeper. Pierre Cartier, a visiteur de longue durée ("long-term

guest") at the IHÉS, wrote a piece about Grothendieck for a

special volume published on the occasion of the IHÉS's fortieth

anniversary. The Grothendieck Festschrift was a three-volume collection of research papers to mark his sixtieth birthday (falling in 1988), and published in 1990. In his article Cartier notes that, as the son of an antimilitary anarchist and one

who grew up among the disenfranchised, Grothendieck always had a deep

compassion for the poor and the downtrodden. As Cartier puts it,

Grothendieck came to find Bures-sur-Yvette "une cage dorée"

("a golden cage"). While Grothendieck was at the IHÉS,

opposition to the Vietnam War was heating up, and Cartier suggests that

this also reinforced Grothendieck's distaste at having become a

mandarin of the scientific world. In addition, after several years at

the IHÉS Grothendieck seemed to cast about for new intellectual

interests. By the late 1960s he had started to become interested in

scientific areas outside of mathematics. David Ruelle,

a physicist who joined the IHÉS faculty in 1964, said that

Grothendieck came to talk to him a few times about physics. Biology interested Grothendieck much more than

physics, and he organized some seminars on biological topics. After leaving the IHÉS, Grothendieck tried but failed to get a position at the Collège de France. He

then went to Université de Montpellier, where he became

increasingly estranged from the mathematical community. Around this

time, he founded a group called Survivre, which was dedicated to

antimilitary and ecological issues. His mathematical career, for the

most part, ended when he left the IHÉS. In 1984 he wrote a

proposal to get a position through the Centre National de la Recherche

Scientifique. The proposal, entitled Esquisse d'un Programme ("Program

Sketch") describes new ideas for studying the moduli space of complex

curves. Although Grothendieck himself never published his work in this

area, the proposal became the inspiration for work by other

mathematicians and the source of the theory of dessin d'enfants. Esquisse d’un Programme was published in the two-volume proceedings Geometric Galois Actions (Cambridge University Press, 1997). While

not publishing mathematical research in conventional ways during the

1980s, he produced several influential manuscripts with limited

distribution, with both mathematical and biographical content. During

that period he also released his work on Bertini type theorems

contained in EGA 5, published by the Grothendieck Circle in 2004. La Longue Marche à travers la théorie de Galois [The Long March Through Galois Theory]

is an approximately 1600-page handwritten manuscript produced by

Grothendieck during the years 1980–1981, containing many of the ideas

leading to the Esquisse d'un programme, and in particular studying the Teichmüller theory. In 1983 he wrote a huge extended manuscript (about 600 pages) entitled Pursuing Stacks, stimulated by correspondence with Ronald Brown, and starting with a letter addressed to Daniel Quillen.

This letter and successive parts were distributed from Bangor: in an informal manner, as a kind of diary,

Grothendieck explained and developed his ideas on the relationship

between algebraic homotopy theory and algebraic geometry and prospects for a noncommutative theory of stacks. The manuscript, which is being edited for publication by G. Maltsiniotis, later led to another of his monumental works, Les Dérivateurs. Written in 1991, this latter opus of about 2000 pages further developed the homotopical ideas begun in Pursuing Stacks. Much of this work anticipated the subsequent development of the motivic homotopy theory of F. Morel and V. Voevodsky in the mid 1990s. His Esquisse d'un programme (1984) is a proposal for a position at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique,

which he held from 1984 to his retirement in 1988. Ideas from it have

proved influential, and have been developed by others, in particular dessins d'enfants and a new field emerging as anabelian geometry. In La Clef des Songes he explains how the reality of dreams convinced him of God's existence. The 1000-page autobiographical manuscript Récoltes et semailles (1986)

is now available on the internet in the French original, and an English

translation is underway. Some parts of Récoltes et semailles and the whole La Clef des Songes have been translated into Spanish. In

1991, Grothendieck moved to an address he did not provide to his

previous contacts in the mathematical community. He is now said to live

in southern France or Andorra and to be reclusive. In January 2010, Grothendieck wrote a letter to Luc Illusie.

In this "Declaration d’intention de non-publication", he states that

essentially all materials that have been published in his absence have

been done without his permission. He asks that none of his work should

be reproduced in whole or in part, and even further that libraries

containing such copies of his work remove them.