<Back to Index>

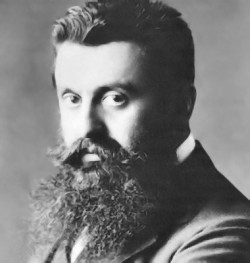

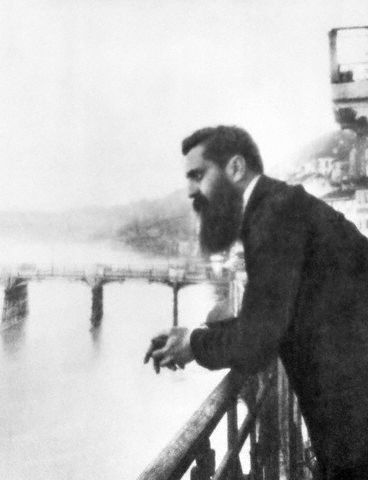

- Journalist and Political Philosopher Theodor Herzl, 1860

- Photographer Philippe Halsman, 1906

- Empress of Russia Catherine II, 1729

Theodor Herzl (Hebrew: בנימין זאב הרצל, Binyamin Ze'ev Herzl, also known as חוזה המדינה, Hoze Ha'Medinah (lit. "visionary of the State")) (May 2, 1860 — July 3, 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian journalist and the father of modern political Zionism.

Theodor Herzl was born in Pest to a Jewish family originally from Zemun, Austrian Empire (politically, city of Zemun is in Serbia today). When Theodor was 18, his family moved to Vienna, Austria-Hungary, where he studied law. After a brief legal career in Vienna and Salzburg, he devoted himself to journalism and literature, working as a correspondent for the Neue Freie Presse in Paris, occasionally making special trips to London and Istanbul. Later, he became literary editor of Neue Freie Presse, and wrote several comedies and dramas for the Viennese stage. As a young man, Herzl was engaged in a Burschenschaft association, which strove for German unity under the motto Ehre, Freiheit, Vaterland ("Honor, Freedom, Fatherland"), and his early work did not focus on Jewish life. His work was of the feuilleton order, descriptive rather than political. As the Paris correspondent for Neue Freie Presse, Herzl followed the Dreyfus Affair, a notorious anti-Semitic incident in France in which a French Jewish army captain was falsely convicted of spying for Germany.

He witnessed mass rallies in Paris following the Dreyfus trial where

many chanted "Death to the Jews!" Herzl came to reject his early ideas

regarding Jewish emancipation and assimilation, and to believe that the Jews must remove themselves from Europe and create their own state. In

June, 1895, he wrote in his diary: "In Paris, as I have said, I

achieved a freer attitude toward anti-Semitism... Above all, I

recognized the emptiness and futility of trying to 'combat'

anti-Semitism." However, in recent decades historians have downplayed

the influence of the Dreyfus Affair on Herzl, even terming it a myth. They have shown that, while upset by anti-Semitism evident in French society,

he, like most contemporary observers, initially believed in Dreyfus's

guilt and only claimed to have been inspired by the affair years later

when it had become an international cause celebre. Rather, it was the rise to power of the anti-Semitic demagogue Karl Lueger in

Vienna in 1895 that seems to have had a greater effect on Herzl, before

the pro-Dreyfus campaign had fully emerged. It was at this time that he

wrote his play "The New Ghetto", which shows the ambivalence and lack

of real security and equality of emancipated, well-to-do Jews in

Vienna. Around this time Herzl grew to believe that anti-Semitism could

not be defeated or cured, only avoided, and that the only way to avoid

it was the establishment of a Jewish state. In Der Judenstaat he writes: From April, 1896, when the English translation of his Der Judenstaat (The State of the Jews) appeared, Herzl became the leading spokesman for Zionism, although Herzl later on had confessed to his friend Max Bodenheimer,

that he "wrote what I had to say without knowing my predecessors, and

it can be assumed that I would not have written it, had I been familiar

with the literature". Herzl complemented his writing with practical work to promote Zionism on the international stage. He visited Istanbul in April, 1896, and was hailed at Sofia, Bulgaria, by a Jewish delegation. In London, the Maccabees group received him coldly, but he was granted the mandate of leadership from the Zionists of the East End of London.

Within six months this mandate had been approved throughout Zionist

Jewry, and Herzl traveled constantly to draw attention to his cause.

His supporters, at first few in number, worked night and day, inspired

by Herzl's example. In

June 1896, with the help of the sympathetic Polish emigre aristocrat

Count Philip Michael Nevlenski, he met for the first time with the Sultan of Turkey to put forward his proposal for a Jewish state in Palestine. However the Sultan refused to cede Palestine to

Zionists, saying, "if one day the Islamic State falls apart then you

can have Palestine for free, but as long as I am alive I would rather

have my flesh be cut up than cut out Palestine from the Muslim land." In 1897, at considerable personal expense, he founded Die Welt of Vienna, Austria-Hungary and planned the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland.

He was elected president (a position he held until his death in 1904),

and in 1898 he began a series of diplomatic initiatives intended to

build support for a Jewish country. He was received by the German emperor on several occasions, one of them in Jerusalem, and attended The Hague Peace Conference, enjoying a warm reception by many other statesmen. In

1902–03 Herzl was invited to give evidence before the British Royal

Commission on Alien Immigration. The appearance brought him into close

contact with members of the British government, particularly with Joseph Chamberlain, then secretary of state for the colonies, through whom he negotiated with the Egyptian government for a charter for the settlement of the Jews in Al 'Arish, in the Sinai Peninsula, adjoining southern Palestine. In 1903, Herzl attempted to obtain support for the Jewish homeland from Pope Pius X. Cardinal Rafael Merry del Val explained to him the Church's policy of non possumus on

such matters, saying that as long as the Jews deny the divinity of

Christ, the Church certainly could not make a declaration in their

favor. On the failure of that scheme, which took him to Cairo, he received, through L.J. Greenberg,

an offer (August 1903) on the part of the British government to

facilitate a large Jewish settlement, with autonomous government and

under British suzerainty, in British East Africa. At the same time, the Zionist movement being threatened by the Russian government, he visited St. Petersburg and was received by Sergei Witte, then finance minister, and Viacheslav Plehve,

minister of the interior, the latter of whom placed on record the

attitude of his government toward the Zionist movement. On that

occasion Herzl submitted proposals for the amelioration of the Jewish

position in Russia. He published the Russian statement, and brought the British offer, commonly known as the "Uganda Project,"

before the Sixth Zionist Congress (Basel, August 1903), carrying the

majority (295:178, 98 abstentions) with him on the question of

investigating this offer, after the Russian delegation stormed out. In

1905, after investigation, the Congress decided to decline the British

offer and firmly committed itself to a Jewish homeland in the historic Land of Israel. Herzl did not live to see the rejection of the Uganda plan; he died in Edlach, Lower Austria in

1904 of heart failure at age 44. His will stipulated that he should

have the poorest-class funeral without speeches or flowers and he

added, "I wish to be buried in the vault beside my father, and to lie

there till the Jewish people shall take my remains to Palestine". In 1949 his remains were moved from Vienna to be reburied on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem. Der Judenstaat (in English: The Jewish State, 1896) written in German, was the book that announced the advent of Zionism to the world, in the form of a pamphlet-length political program. His last literary work, Altneuland (in English: The Old New Land, 1902), is a novel devoted

to Zionism. Herzl occupied his free time for three years in writing

what he believed might be accomplished by 1923. It is less a novel,

though the form is that of romance, than a serious forecasting of what

could be done within one generation. The keynotes of the story are the

love for Zion,

the insistence upon the fact that the changes in life suggested are not

utopian, but are to be brought about simply by grouping all the best

efforts and ideals of every race and nation; and each such effort is

quoted and referred to in such a manner as to show that Altneuland,

though blossoming through the skill of the Jew, will in reality be the

product of the benevolent efforts of all the members of the human

family. Herzl envisioned a Jewish state which combined both a modern Jewish culture with the best of the European heritage. Thus a Palace of Peace would be built in Jerusalem, arbitrating international disputes, and at the same time the Temple would be rebuilt on modern principles. Herzl did not envision the Jewish inhabitants of the state being religious, but there would be much respect for religion in the public sphere. He also assumed that many languages would be spoken, but Hebrew would not be the main tongue. Proponents of a Jewish cultural rebirth, such as Ahad Ha'am were critical of Altneuland. In Altneuland, Herzl did not foresee any conflict between Jews and Arabs. One of the main characters in Altneuland is

a Haifa engineer, Reshid Bey, who is one of the leaders of the "New

Society", is very grateful to his Jewish neighbors for improving the

economic condition of Palestine and sees no cause for conflict. All

non-Jews have equal rights, and an attempt by a fanatical rabbi to

disenfranchise the non-Jewish citizens of their rights fails in the

election which is the center of the main political plot of the novel. Herzl

also envisioned the future Jewish state to be a "third way" between

capitalism and socialism, with a developed welfare program and public

ownership of the main natural resources and industry, agriculture and

even trade organized on a cooperative basis. He called this mixed

economic model "Mutualism", a term derived from French utopian socialist thinking. Women would have equal voting rights - as they did have in the Zionist movement from the Second Zionist Congress onwards. In

his novel, Herzl wrote about an electoral campaign in the new state. He

directed his wrath against the nationalist party which wished to make

the Jews a privileged class in Palestine. Herzl regarded that as a

betrayal of Zion, for Zion was identical to him with humanitarianism

and tolerance – that this was true in politics as well as in religion. Altneuland was written both for Jews and non-Jews: Herzl wanted to win over non-Jewish opinion for Zionism. When he was still thinking of Argentina as

a possible venue for massive Jewish immigration, he mentioned in his

diary that land was to be gently expropriated from the local

population and they were to be worked across the border "unbemerkt"

(surreptitiously), e.g. by refusing them employment. Herzl's draft of a charter for a Jewish-Ottoman Land Company (JOLC) gave the JOLC the right to obtain land in Palestine by giving its owners comparable land elsewhere in the Ottoman empire. The name of Tel Aviv is the title given to the Hebrew translation of Altneuland by the translator, Nahum Sokolov. This name, which comes from Ezekiel 3:15, means tell—

an ancient mound formed when a town is built on its own debris for

thousands of years— of spring. The name was later applied to the new

town built outside of Jaffa, which went on to become Tel Aviv-Yafo the second-largest city in Israel. The nearby city to the north, Herzlia, was named in honor of Herzl. Herzl's

grandfathers, both of whom he knew, were more closely related to

traditional Judaism than his parents, yet two of his paternal

grandfather's brothers and his maternal grandmother's brother exemplify

complete estrangement and rejection of Judaism on the one hand, and

utter loyalty and devotion to Judaism and Eretz Israel. In Zemun

(Zemlin), Grandfather Simon Loeb Herzl "had his hands on" one of the

first copies of Judah Alkalai's

1857 work prescribing the "return of the Jews to the Holy Land and

renewed glory of Jerusalem." Herzl’s grandparents' graves in Semlin can still be visited. Alkalai

himself, was witness to the rebirth of Serbia from Ottoman rule in the

early and mid 19th century, and was inspired by the Serbian uprising

and subsequent re-creation of Serbia. Jacob

Herzl (1836-1902), Theodor's father, was a highly successful

businessman. Herzl had one sister, Pauline, a year older than he was,

who died suddenly on February 7, 1878 of typhus. Theodor lived with his family in a house next to the Dohány Street Synagogue (formerly known as Tabakgasse Synagogue) located in Belváros, the inner city of the historical old town of Pest, in the eastern section of Budapest. The remains of Herzl's parents and sister were re-buried on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem. In

June, 25, 1889 he married Julie Naschauer, daughter of a wealthy Jewish

businessman in Vienna. The marriage was unhappy, although three

children were born to it. Herzl had a strong attachment to his mother,

who was unable to get along with his wife. These difficulties were

increased by the political activities of his later years, in which his

wife took little interest. All three children died tragically. His

daughter Pauline suffered from mental illness and drug addiction. She

died in 1930 at the age of 40, apparently of a morphine overdose. His

son Hans, a converted Catholic, committed suicide (gunshot) the day of

sister Pauline's funeral. He was 39. In 2006 the remains of Pauline and Hans were moved from Bordeaux, France, and placed alongside their father. The youngest daughter, Trude Margarethe, (officially Margarethe, 1893-1943) married Richard Neumann. He lost his fortune in the economic depression. He was burdened by the steep costs of hospitalizing Trude, who was mentally ill,

and was finding it difficult to raise the money required to send his

son Stephan, 14, to a boarding school in London. After she had spent

many years in hospitals, the Nazis sent Trude to Theresienstadt where she died. Her body was burned. {Likewise her mother who died in 1907 was cremated-her ashes were lost by accident} Trude's son (Herzl's only grandchild), Stephan Theodor Neumann (1918-1946) was sent to England,

1937-1938, for his safety, as rabid Austrian anti-Semitism grew. In

England, he read extensively about his grandfather. Stephan became an

ardent Zionist. He was the only immediate descendant of Herzl to be a

Zionist. Anglicizing his name to Stephen Norman, during World War II, Norman enlisted in the British Army rising to the rank of Captain in the Royal Artillery. In late 1945 and early 1946, he took the opportunity to visit the British Mandate of Palestine "to

see what my grandfather had started." He wrote in his diary extensively

about his trip. What impressed him the most was that there was a "look

of freedom" in the faces of the children, not like the sallow look of

those from the concentration camps of

Europe. He wrote upon leaving Palestine, "My visit to Palestine is

over... It is said that to go away is to die a little. And I know that

when I went away from Erez Israel, I died a little. But sure, then, to

return is somehow to be reborn. And I will return." Once discharged from the military in Britain, he took a minor position with a British Economic and Scientific mission in Washington, D.C. in

Autumn 1946, where he learned that his family had been exterminated. He

became deeply depressed over the fate of his family. Unable to endure

the suffering any further, he jumped from the Massachusetts Avenue Bridge in Washington, D.C. to his death. Norman was buried by the Jewish Agency in

Washington, D.C. His tombstone reads simply, 'Stephen Theodore Norman,

Captain Royal Artillery British Army, Grandson of Theodore Herzl, April

21, 1918 - November 26, 1946'. Norman

was the only member of Herzl's family to have been to Palestine. He was

reburied with his family on Mt. Herzl on December 5, 2007.“ The

Jewish question persists wherever Jews live in appreciable numbers.

Wherever it does not exist, it is brought in together with Jewish

immigrants. We are naturally drawn into those places where we are not

persecuted, and our appearance there gives rise to persecution. This is

the case, and will inevitably be so, everywhere, even in highly

civilised countries—see, for instance, France—so long as the Jewish

question is not solved on the political level. The unfortunate Jews are

now carrying the seeds of anti-Semitism into England; they have already

introduced it into America. ”