<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Karl Heinrich Marx, 1818

- Architect and Painter Viktor Alexandrovich Hartmann, 1834

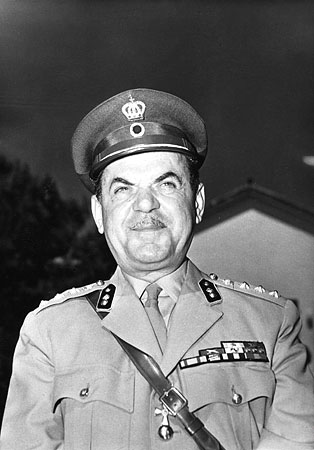

- Dictator of Greece Georgios Papadopoulos, 1919

Georgios Papadopoulos (Greek: Γεώργιος Παπαδόπουλος) (5 May 1919 – 27 June 1999) was the head of the military coup d'état that took place in Greece on 21 April 1967 and leader of the military government that ruled the country from 1967 to 1974.

Papadopoulos was born in Elaiohori, a small village in the Prefecture of Achaea in Peloponnese to local school teacher Christos Papadopoulos and his wife Chrysoula. He was the eldest son and had two brothers, Konstantinos and Haralambos. Upon finishing High School in 1937, he enrolled in the Scholi Evelpidon Officer

Academy (Σχολή Ευελπίδων). He completed his three-year education in

1940. Papadopoulos' biographical notes, that were published as a

booklet by supporters in 1980, mention that he attended a Civil engineering course at the Polytechneion but did not graduate. The 1941 class became the class of 1940B, graduating a year early as a result of Mussolini's invasion. On 28 October 1940, Prime Minister of Greece, Ioannis Metaxas, rejected an Italian ultimatum to allow the occupation of unspecified strategic points within Greek territory by the Italian army. Italy's leader Benito Mussolini had already issued orders for an invasion in that event. Thus Greece entered World War II. Papadopoulos saw field action as a Second Lieutenant of the Artillery against both the Italians and the forces of Nazi Germany, which attacked Greece on 6 April 1941. The Wehrmacht captured Athens on 27 April 1941. Following their victory in the Battle of Crete (20 May - 1 June 1941), Greece was placed under the combined occupation of Nazi Germany, Italy and Bulgaria. A resistance movement soon emerged, including several organizations varying in ideological conviction, popular support, and area of activity. Most significant among them was the left-wing Ellinikos Laïkos Apeleftherotikos Stratos (ELAS), formed by the Communist Party of Greece (KKE)

and the strongest group in terms of numbers. Papadopoulos, an

anti-communist, did not join ELAS or any other resistance group and

instead worked for the "Patras Food Supply Office" of the Greek

administration. The

"Patras Food Supply Office" was run under the command of Colonel

Kourkoulakos, an officer who was responsible for the formation of the "Security Battalions"

in Patras. These battalions were para-military units composed of

anti-communist Greeks, and were created by the Greek government in late

1943 to resist ELAS in its attempt to take power in Greece

following the retreat of the German occupation forces from Greece

(which took place on October 1944). It is fair to say that Papadopoulos

worked under the commands of Kourkoulakos against ELAS. At the beginning of 1944, Papadopoulos left Greece with the help of British intelligence agents and went to Egypt, where the Greek government-in-exile was based, where he received the rank of Lieutenant. Along with other right-wing military

officers, he participated in the creation of the nationalist right-wing

secret IDEA organization, in the fall of 1944, shortly after the

country's liberation. Those 1940B officers who went to Egypt with the

King immediately after the German invasion had attained the rank of

General when their still-colonel classmates undertook the coup of 1967.

Papadopoulos married his first wife Niki Vasileiadi in 1941 and they had two children, a son and a daughter. Their

marriage, however, later fell in difficult times and they eventually

separated. Their separation, although lengthy, initially could not lead

to divorce because, under Greece's restrictive divorce laws of that

era, spousal consent was required. To remedy this, in 1970, as Prime

Minister of the dictatorship he decreed a custom-made divorce law to be passed of very limited duration (built-in sunset clause), that enabled him to get the divorce. The law subsequently, having served its purpose, automatically expired. After his divorce, Papadopoulos married his long-time paramour Despina Gaspari in 1970 with whom he had a daughter. In 1956, Papadopoulos took part in a failed coup attempt against Paul of Greece. In 1958, he helped create the Office of Military Studies, a surveillance authority, under General Gogousis. It was from this same office that the subsequently successful coup of 21 April 1967 emerged. In 1964, he was transferred to an artillery division in Thrace by decree of the Center Union defense minister Garoufalias. In June 1965, days before the major political turmoil known as Apostasia,

Papadopoulos reached national headlines. He arrested two soldiers under

his command and eight leftist civilians from settlements near his

military camp, under the charges that they had conspired to sabotage army

vehicles by pouring sugar into the vehicles' gas tanks. The ten people

were imprisoned and tortured, but eventually it was proven that

Papadopoulos himself had sabotaged the vehicles. Andreas Papandreou wrote

in his memoirs that Papadopoulos wanted to prove that under the Center

Union government, the communists had been let free to undermine

national security. However, Papadopoulos was not discharged from the army, as prime minister Georgios Papandreou forgave him on the grounds that Papadopoulos was a compatriot of his father. In 1967, Papadopoulos was promoted to Colonel. The

same year, on 21 April (one month before the general elections)

Papadopoulos, along with fellow middle-ranking Army officers, led a

successful coup, taking advantage of the volatile political situation

that had arisen from a conflict between King Constantine II and the aging former prime minister, Georgios Papandreou. Papadopoulos attempted to re-engineer the Greek political landscape by coup. In

Greece even today the words "21η Απριλίου 1967", translated as 21 April

1967, are still synonymous with the word "πραξικόπημα" that translates

as coup d'état. From

the early stages Papadopoulos emerged as the strong man of the new

regime. He was appointed Minister of National Defence and Minister of

the Presidency in the first government, and his position was further

enhanced when, after the King's abortive counter-coup on 13 December he

became Prime Minister. Furthermore, on 21 March 1972, he nominated

himself as Regent of Greece, succeeding Georgios Zoitakis. Papadopoulos' regime imposed martial law, censorship, mass arrests, beatings and torture.

Thousands of the regime's political opponents, were thrown into prison

or were exiled (or "forced into vacation" according to the regime's

friends) on small Aegean islands. (Amnesty International issued

a report detailing numerous instances of torture under the egime;

Papadopoulos excused these actions by stating that they were being done

to save the nation from a "communist takeover". Because of the regime's

staunchly anti-communist stance, it was strongly supported by the United States. Many Greeks felt confirmed in their belief of USA backing and even complicity in the coup by Bill Clinton's public apology for that support on behalf of the USA, during his November 1999 visit in Greece. The

military government dissolved political parties, clamped down on left

wing organizations and labor unions, and promoted a traditionalist

Greco-Christian culture. At the same time, however, the economy, due

mostly to the political stability brought by the regime, was greatly

improved and extensive public works, such as highway-building, reforms

re: agricultural matters and electrification, were carried out all over

Greece but especially in the mostly backward rural areas. Torture

of the incarcerated, especially on fanatic communists, was not out of

the question. A failed assassination attempt was made against Papadopoulos by Alexandros Panagoulis in the morning of 13 August 1968, when Papadopoulos went from his summer residence in Lagonisi to Athens,

escorted by his personal security motorcycles and cars. Panagoulis

ignited a bomb at a point of the coastal road where the limousine

carrying Papadopoulos would have to slow down but the bomb failed to

harm Papadopoulos. Panagoulis was captured a few hours later in a

nearby sea cave as the boat that would let him escape was instructed to

leave at a specific time and he couldn't swim there on time due to the

strong sea currents. Panagoulis was arrested, and transferred to the Greek Military Police (EAT-ESA)

offices were he was questioned, beaten and tortured. On 17 November

1968, he was sentenced to death, and remained for five years in prison.

After the restoration of Democracy, Panagoulis was elected a member of

Parliament. Panagoulis was regarded as an emblematic figure for the

struggle to restore Democracy. He has often been paralleled to Harmodius and Aristogeiton, two ancient Athenians, known for the tyrannicide of the Athenian tyrant Hipparchus. Papadopoulos

had indicated as early as 1968 that he was eager for a reform process

and even tried to contact Markezinis at the time. He had declared at the time that he did not want the Revolution (junta speak for the dictatorship) to become a regime. He then repeatedly attempted to initiate reforms in 1969 and 1970, only to be thwarted by the hardliners including Ioannides. In

fact subsequent to his 1970 failed attempt at reform, he threatened to

resign and was dissuaded only after the hardliners renewed their

personal allegiance to him. As internal dissatisfaction grew in the early 1970s, and especially after an abortive coup by the Navy in early 1973, Papadopoulos attempted to legitimize the regime by beginning a gradual "democratization".

On 1 June 1973, he abolished the monarchy and declared himself

President of the Republic after a controversial referendum. He

furthermore sought the support of the old political establishment, but

secured only the cooperation of Spiros Markezinis,

who became Prime Minister. Concurrently, many restrictions were lifted,

and the army's role significantly reduced. Papadopoulos intended to

establish a presidential republic,

with extensive powers vested in the office of President, which he held.

The decision to return to political rule and the restriction of their

role was resented by many of the regime's supporters in the Army, whose

dissatisfaction with Papadopoulos would become evident a few months

later. After the events of the student uprising of November 17 at the National Technical University of Athens,

his government was overthrown on 25 November 1973 by hard-line elements

in the Army. The outcry over Papadopoulos's extensive reliance on the

army to quell the student uprising gave Brigadier Dimitrios Ioannides a

pretext to oust him and replace him as the new strong man of the

regime. Papadopoulos was put under house arrest at his villa, while

Greece returned to an 'orthodox' military dictatorship. After democracy was restored in 1974, during the period of metapolitefsi ("regime change"), Papadopoulos and his cohorts were tried for high treason, mutiny, torture and other crimes and misdemeanours. On 23 August 1975 he and several others were found guilty and were sentenced to death, which was later commuted to a life sentence. Papadopoulos remained in prison, rejecting an amnesty offer

that required that he acknowledge his past record and express remorse,

until his death on 27 June 1999 at age 80 when he succumbed to cancer.

In 1946, he received the rank of Captain and, in 1949, during the Greek Civil War, he rose to the rank of Major. He served at the KYP Intelligence Service from 1959 to 1964 as the main contact between the KYP and the top CIA operative in Greece, John Fatseas, after receiving training from the CIA in 1953. Papadopoulos was also a member of the court-martial in the first trial of the well-known Greek communist leader Nikos Beloyannis in

1951. At that trial, Beloyannis was sentenced to death for the crime of

being a member of the Communist Party, which was banned at that time in

Greece following the Greek Civil War.

The death sentence pronounced after this trial (Papadopoulos had voted

against it) was not carried out, but Beloyannis was put to trial again

in early 1952, this time for alleged espionage, following the discovery

of radio transmitters used by undercover Greek communists to

communicate with the exiled leadership of the Party in the Soviet Union.

At the end of this trial, he was sentenced to death and immediately

shot. Papadopoulos was not involved in this second trial. The

Beloyannis trials are highly controversial in Greece and many Greeks

consider that, like many Greek communists at the time, Beloyannis was

shot for his political beliefs,

rather than any real crimes. The trial was by court-martial under Greek

anti-insurgency legislation dating from the time of the Greek Civil War that remained in force even though the war had ended.