<Back to Index>

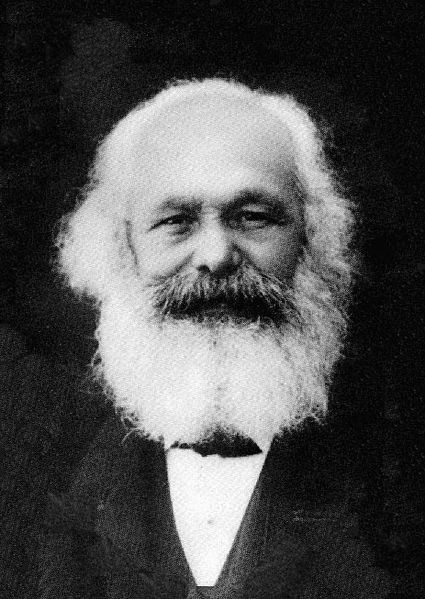

- Philosopher Karl Heinrich Marx, 1818

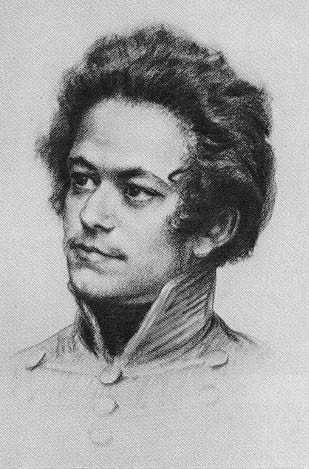

- Architect and Painter Viktor Alexandrovich Hartmann, 1834

- Dictator of Greece Georgios Papadopoulos, 1919

Karl Heinrich Marx (May 5, 1818 – March 14, 1883) was a German philosopher, political economist, historian, political theorist, sociologist, communist, and revolutionary, whose ideas are credited as the foundation of modern communism. Marx summarized his approach in the first line of chapter one of The Communist Manifesto, published in 1848: "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles."

Marx argued that capitalism, like previous socioeconomic systems, would inevitably produce internal tensions which would lead to its destruction. Just as capitalism replaced feudalism, he believed socialism would, in its turn, replace capitalism, and lead to a stateless, classless society called pure communism. This would emerge after a transitional period called the "dictatorship of the proletariat": a period sometimes referred to as the "workers state" or "workers' democracy". Marx argued for a systemic understanding of socio-economic change. He argued that the structural contradictions within capitalism necessitate its end, giving way to socialism. On the other hand, Marx argued that socio-economic change occurred through organized revolutionary action. He argued that capitalism will end through the organized actions of an international working class: "Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality will have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things. The conditions of this movement result from the premises now in existence."

While Marx remained a relatively obscure figure in his own lifetime, his ideas and the ideology of Marxism began to exert a major influence on workers' movements shortly after his death. This influence gained added impetus with the victory of the Bolsheviks in the Russian October Revolution in 1917, and few parts of the world remained significantly untouched by Marxian ideas in the course of the twentieth century. Marx is typically cited, with Émile Durkheim and Max Weber, as one of the three principal architects of modern social science.

Karl Heinrich Marx was born in Trier, in the Kingdom of Prussia's Province of the Lower Rhine. His father, Heinrich Marx, was born a Jew but converted to Lutheranism prior to Karl's birth, in part in order to advance his career as a lawyer. A man of the Enlightenment, Heinrich was devoted to Kant and Voltaire, who took part in agitations for a constitution in Prussia. Karl's mother, born Henrietta Pressburg, was from Holland, and Jewish at the time of Karl's birth, although she converted upon the death of her parents. Karl was baptized when he was six years old. Marx's parents had him educated at home until the age of twelve. After graduating from the Trier Gymnasium, Marx enrolled in the University of Bonn in 1835 at the age of seventeen; he wished to study philosophy and literature, but his father insisted on law as a more practical field of study. At Bonn he joined the Trier Tavern Club drinking society (Landsmannschaft der Treveraner) and at one point served as its president. Because of Marx's poor grades, his father forced him to transfer to the far more serious and academically oriented University of Berlin, where his legal studies became less significant than excursions into philosophy and history.

During this period, Marx wrote many poems and essays concerning life,

using the theological language acquired from his liberal, deistic

father, such as "the Deity," but also absorbed the atheistic philosophy

of the Young Hegelians who were prominent in Berlin at the time. Marx earned a doctorate in 1841 with a thesis titled The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature, but he had to submit his dissertation to the University of Jena as he was warned that his reputation among the faculty as a Young Hegelian radical would lead to a poor reception in Berlin.

Marx was influenced in his formative school years by Immanuel Kant and Voltaire.

They were among his favorite authors, representing even early on his

characteristic blend of German profundity and French subversive wit. The Left or Young Hegelians consisted of a group of philosophers and journalists circling around Ludwig Feuerbach and Bruno Bauer, and opposing their teacher Hegel. Despite their criticism of Hegel's metaphysical assumptions,

they made use of Hegel's dialectical method as a powerful weapon for

the critique of established politics and religion. One of them, Max Stirner, turned critically against both Feuerbach and Bauer in his book "Der Einzige und sein Eigenthum" (1845, The Ego and Its Own), calling these atheists "pious people" for the irreification of abstract concepts. Stirner's work made a deep impression on Marx, at that time a follower of Feuerbach: he abandoned Feuerbachian materialism and accomplished what recent authors have denoted as an "epistemological break." He developed the basic concept of historical materialism against Stirner in his book, "Die Deutsche Ideologie" (1846, The German Ideology), which he did not publish. Another link to the Young Hegelians was Moses Hess,

with whom Marx eventually disagreed, yet to whom he owed many of his

insights into the relationship between state, society, and religion.

During his years at college, the official lectures on Hegel left Marx

feeling ill, "from intense vexation at having to make an idol of a view

I detested." Owing to the conditions of censorship in Prussia, Marx retired from the editorial board of the Rheinische Zeitung, and planned to publish, with Arnold Ruge, another revolutionary from Germany, the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, (the German-French Yearbook)

based in Paris, and arrived in late October 1843. Paris at this time

served as the home and headquarters of German, British, Polish, and

Italian revolutionaries. In Paris, on August 28, 1844, at the Café de la Régence on

the Place du Palais he met Friedrich Engels, who would become his most

important friend and life-long companion. Engels had met Marx only once

before (and briefly) at the office of the Rheinische Zeitung in 1842; he went to Paris to show Marx his recently published book, The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844. This book convinced Marx that the working class would be the agent and instrument of the final revolution in history. After the failure of the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, Marx, living on the rue Vaneau, wrote for the most radical of all German newspapers in Paris, indeed in Europe, Vorwärts, established and run by the secret society called League of the Just. When not writing, Marx studied the history of the French Revolution and read Proudhon. He also spent considerable time studying a side of life he had never been acquainted with before: a large urban proletariat. Marx re-evaluated his relationship with the Young Hegelians, and as a reply to Bauer's atheism wrote On the Jewish Question. This essay consisted mostly of a critique of current notions of civil and human rights and political emancipation; it also included several critical references to Judaism as well as Christianity from a standpoint of social emancipation. Engels, a committed communist, kindled Marx's interest in the situation of the working class and guided Marx's interest in economics. Marx became a communist and set down his views in a series of writings known as the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844, which remained unpublished until the 1930s. In the Manuscripts, Marx outlined a humanist conception of communism, influenced by the philosophy of Ludwig Feuerbach and

based on a contrast between the alienated nature of labor under

capitalism and a communist society in which human beings freely

developed their nature in cooperative production. In January 1845, after Vorwärts expressed its hearty approval of an assassination attempt on Frederick William IV, King of Prussia, the French authorities ordered Marx, among many others, to leave Paris. He and Engels moved on to Brussels in Belgium. Marx

devoted himself to an intensive study of history, and in collaboration

with Engels elaborated on his idea of historical materialism,

particularly in a manuscript (published posthumously as The German Ideology),

which stated as its basic thesis that "the nature of individuals

depends on the material conditions determining their production". Marx

traced the history of the various modes of production and predicted the

collapse of the present one—industrial capitalism—and its replacement

by communism. This was the first major work of what scholars consider

to be his later phase, abandoning the Feuerbach-influenced humanism of

his earlier work. Next, Marx wrote The Poverty of Philosophy (1847), a response to Pierre-Joseph Proudhon's The Philosophy of Poverty and a critique of French socialist thought. These works laid the foundation for Marx and Engels' most famous work, The Communist Manifesto, first published on February 21, 1848 as the manifesto of the Communist League,

a small group of European communists who had come under the influence

of Marx and Engels. Later that year, Europe experienced a series of

protests, rebellions, and often violent upheavals, the Revolutions of 1848. The Belgian authorities arrested and expelled Marx from Belgium. In February 1848 a radical movement seized power from King Louis-Philippe in France and invited Marx to return to Paris, where he witnessed the revolutionary June Days Uprising first hand. When this collapsed in 1849, Marx moved back to Cologne and started the Neue Rheinische Zeitung ("New

Rhenish Newspaper"). During its existence he went on trial twice, on

February 7, 1849 because of a press misdemeanor, and on the 8th charged

with incitement to armed rebellion. Both times he was acquitted. The

paper was soon suppressed and Marx returned to Paris, but was forced

out again. This time he sought refuge in London. Marx

moved to London in May 1849 and remained there for the rest of his

life. For the first few years there, he and his family lived in extreme

poverty. He briefly worked as correspondent for the New York Tribune in 1851. In London Marx devoted himself to two activities: revolutionary organizing, and an attempt to understand political economy and capitalism. Having read Engels' study of the working class, Marx turned away from philosophy and devoted himself to the First International,

to whose General Council he was elected at its inception in 1864. He

was particularly active in preparing for the annual Congresses of the

International and leading the struggle against the anarchist wing led by Mikhail Bakunin (1814–1876).

Although Marx won this contest, the transfer of the seat of the General

Council from London to New York in 1872, which Marx supported, led to

the decline of the International. The most important political event

during the existence of the International was the Paris Commune of 1871 when

the citizens of Paris rebelled against their government and held the

city for two months. On the bloody suppression of this rebellion, Marx

wrote one of his most famous pamphlets, The Civil War in France, a defense of the Commune. Given

the repeated failures and frustrations of workers' revolutions and

movements, Marx also sought to understand capitalism, and spent a great

deal of time in the British Library studying and reflecting on the works of political economists and on economic data. By 1857 he had accumulated over 800 pages of notes and short essays on capital, landed,

wage labour, the state, foreign trade and the world market; this work

however did not appear in print until 1941, under the title Grundrisse. In 1859, Marx published Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, his first serious economic work. In the early 1860s he worked on composing three large volumes, the Theories of Surplus Value, which discussed the theoreticians of political economy, particularly Adam Smith and David Ricardo. This work, that was published posthumously under the editorship of Karl Kautsky is often seen as the Fourth book of Capital, and constitutes one of the first comprehensive treatises on the history of economic thought. In 1867, well behind schedule, the first volume of Capital was published, a work which analyzed the capitalist process of production. Here, Marx elaborated his labor theory of value and his conception of surplus value and exploitation which

he argued would ultimately lead to a falling rate of profit and the

collapse of industrial capitalism. Volumes II and III remained mere

manuscripts upon which Marx continued to work for the rest of his life

and were published posthumously by Engels. During

the last decade of his life, Marx's health declined and he became

incapable of the sustained effort that had characterized his previous

work. He did manage to comment substantially on contemporary politics,

particularly in Germany and Russia. His Critique of the Gotha Programme opposed the tendency of his followers Wilhelm Liebknecht (1826–1900) and August Bebel (1840–1913) to compromise with the state socialism of Ferdinand Lassalle in the interests of a united socialist party. Karl Marx married Jenny von Westphalen, the educated daughter of a Prussian baron, on June 19, 1843 in the Pauluskirche, at Bad Kreuznach. Marx and Jenny had seven children, but due to poverty, only three survived to adulthood. Marx's major source of income was from the support of Friedrich Engels, who was drawing a steadily increasing income from the family business in Manchester. This was supplemented by weekly articles written as a foreign correspondent for the New York Daily Tribune. Inheritances from one of Jenny's uncles and her mother who died in 1856 allowed the

family to move to somewhat more salubrious lodgings at 9 Grafton

Terrace, Kentish Town, a

new suburb on the then-outskirts of London. Marx generally lived a

hand-to-mouth existence, forever at the limits of his resources,

although this did to some extent depend upon his spending on relatively bourgeois luxuries,

which he felt were necessities for his wife and children given their

social status and the mores of the time. Marx had seven children by his

wife and also fathered an illegitimate son by his housekeeper, Helene Demuth. Following the death of his wife Jenny in December 1881, Marx developed a catarrh that kept him in ill health for the last 15 months of his life. It eventually brought on the bronchitis and pleurisy that killed him in London on March 14, 1883. He died a stateless person; family and friends in London buried his body in Highgate Cemetery, London, on March 17, 1883. Several of Marx's closest friends spoke at his funeral, including Wilhelm Liebknecht and Friedrich Engels. In addition to Engels and Liebknecht, Marx's daughter Eleanor and Charles Longuet and Paul Lafargue,

Marx's two French socialist sons-in-law, also attended his funeral.

Liebknecht, a founder and leader of the German Social-Democratic Party,

gave a speech in German, and Longuet, a prominent figure in the French

working-class movement, made a short statement in French. Two telegrams from

workers' parties in France and Spain were also read out. Together with

Engels's speech, this constituted the entire programme of the funeral.

Those attending the funeral included Friedrich Lessner, who had been

sentenced to three years in prison at the Cologne communist trial of

1852; G. Lochner, who was described by Engels as "an old member of the

Communist League" and Carl Schorlemmer, a professor of chemistry in Manchester, a member of the Royal Society, but also an old communist associate of Marx and Engels. Three others attended the funeral—Ray Lankester, Sir John Noe and Leonard Church. The Communist Party of Great Britain had

the monumental tombstone built in 1954 with a portrait bust by Laurence

Bradshaw; Marx's original tomb had had only humble adornment. In 1970 there was an unsuccessful attempt to destroy the monument using a homemade bomb.