<Back to Index>

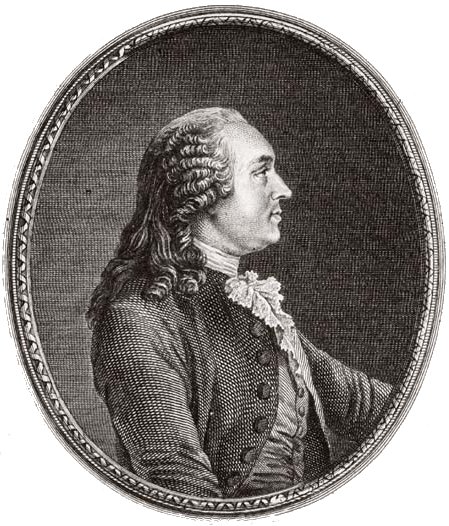

- Political Economist Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, 1727

- Sculptor Carl Eldh, 1873

- Chancellor of Germany Gustav Stresemann, 1878

Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, Baron de Laune (10 May 1727 – 18 March 1781), often referred to as Turgot, was a French economist and statesman. Today he is best remembered as an early advocate for economic liberalism.

Born in Paris, he was the youngest son of Michel-Étienne Turgot, "Provost of the merchants" of Paris, and Madeleine Francoise Martineau de Brétignolles, and came of an old Norman family. He was educated for the Church, and at the Sorbonne, to which he was admitted in 1749 (being then styled abbé de Brucourt). He delivered two remarkable Latin dissertations, On the Benefits which the Christian Religion has conferred on Mankind, and On the Historical Progress of the Human Mind. The first sign we have of his interest in economics is a letter (1749) on paper money, written to his fellow student the abbé de Cicé, refuting the abbé Jean-Baptiste Terrasson's defence of John Law's system. He was fond of verse-making, and tried to introduce into French verse the rules of Latin prosody, his translation of the fourth book of the Aeneid into classical hexameter verses being greeted by Voltaire as the only prose translation in which he had found any enthusiasm. He decided not to take holy orders, giving as his reason, according to Dupont de Nemours, "that he could not bear to wear a mask all his life."

The first complete statement of the Idea of Progress is

that of Turgot, in his "A Philosophical Review of the Successive

Advances of the Human Mind" (1750). For Turgot progress covers not

simply the arts and sciences but, on their base, the whole of

culture — manner, mores, institutions, legal codes, economy, and society. In 1752 he became substitut, and later conseiller in the parlement of Paris, and in 1753 maître des requêtes. In 1754 he was a member of the chambre royale which sat during an exile of the parlement. In Paris he frequented the salons, especially those of Mme de Graffigny — whose niece, Mlle de Ligniville ("Minette"), later Mme Helvétius, he is supposed at one time to have wished to marry; they remained lifelong friends — Mme Geoffrin, Mme du Deffand, Mlle de Lespinasse and the duchesse d'Enville. It was during this period that he met the leaders of the "physiocratic" school, Quesnay and Vincent de Gournay, and with them Dupont de Nemours, the abbé Morellet and other economists. In 1743 and 1756 he accompanied Gournay, the intendant of

commerce, during Gournay's tours of inspection in the provinces.

(Gournay's bye-word on the government's proper involvement in the

economy — "laisser faire, laisser passer" — would pass into the vocabulary of economics.) In 1760, while travelling in the east of France and Switzerland, he visited Voltaire,

who became one of his chief friends and supporters. All this time he

was studying various branches of science, and languages both ancient

and modern. In 1753 he translated the Questions sur le commerce from the English of Josias Tucker, and in 1754 he wrote his Lettre sur la tolérance civile, and a pamphlet, Le Conciliateur, in support of religious tolerance. Between 1755 and 1756 he composed various articles for the Encyclopédie, and between 1757 and 1760 an article on Valeurs des monnaies, probably for the Dictionnaire du commerce of the abbé Morellet. In 1759 appeared his work Eloge de Gournay. In August 1761 Turgot was appointed intendant (tax collector) of the genéralité of Limoges,

which included some of the poorest and most over-taxed parts of France;

here he remained for thirteen years. He was already deeply imbued with

the theories of Quesnay and Gournay, and set to work to apply them as

far as possible in his province. His first plan was to continue the

work, already initiated by his predecessor Tourny, of making a fresh

survey of the land (cadastre), in order to arrive at a more just assessment of the taille ; he also obtained a large reduction in the contribution of the province. He published his Avis sur l'assiette et la repartition de la taille (1762–1770), and as president of the Société d'agriculture de Limoges offered prizes for essays on the principles of taxation. Quesnay and Mirabeau had advocated a proportional tax (impôt de quotité), but Turgot proposed a distributive tax (impôt de repartition). Another reform was the substitution for the corvée of

a tax in money levied on the whole province, the construction of roads

being handed over to contractors, by which means Turgot was able to

leave his province with a good system of highways, while distributing

more justly the expense of their construction. In 1769 he wrote his Mémoire sur les prêts à intérêt, on the occasion of a scandalous financial crisis at Angoulême, the particular interest of which is that in it the question of lending money at interest was

for the first time treated scientifically, and not merely from the

ecclesiastical point of view. Turgot's opinion was that a compromise

had to be reached between both methods. Among other works written

during Turgot's intendancy were the Mémoire sur les mines et carrières, and the Mémoire sur la marque des fers,

in which he protested against state regulation and interference and

advocated free competition. At the same time he did much to encourage

agriculture and local industries, among others establishing the

manufacture of porcelain at Limoges. During the famine of 1770–1771 he enforced on landowners "the obligation of relieving the poor" and especially the métayers dependent upon them, and organized in every province ateliers and bureaux de charité for providing work for the able-bodied and relief for the infirm, while at the same time he condemned indiscriminate charity.

It may be noted that Turgot always made the curés the agents of

his charities and reforms when possible. It was in 1770 that he wrote

his famous Lettres sur la liberté du commerce des grains, addressed to the controller-general, the abbé Terray. Three of these letters have disappeared, having been sent to Louis XVI by Turgot at a later date and never recovered, but those remaining demonstrate that free trade in

grain is to the interest of landowner, farmer and consumer alike, and

in too forcible terms demand the removal of all restrictions. Turgot's best known work, Réflexions sur la formation et la distribution des richesses (Reflections

on the Formation and Distribution of Wealth), was written early in the

period of his intendancy, ostensibly for the benefit of two young

Chinese students. Written in 1766, it appeared in 1769–1770 in Dupont's journal, the Ephémérides du citoyen,

and was published separately in 1776. Dupont, however, made various

alterations in the text, in order to bring it more into accordance with

Quesnay's doctrines, which led to a "friendship" between him and Turgot. In the Réflexions, after tracing the origin of commerce, Turgot develops Quesnay's theory that the land is the only source of wealth, and divides society into three classes, the productive or agricultural, the salaried (the classe stipendice) or artisan class, and the land-owning class (classe disponible).

After discussing the evolution of the different systems of cultivation,

the nature of exchange and barter, money, and the functions of capital, he sets forth the theory of the impôt unique, i.e. that only the net product (produit net) of the land should be taxed. In addition he demanded the complete freedom of commerce and industry. Turgot owed his appointment as minister of the navy in July 1774 to Maurepas, the "Mentor" of Louis XVI,

to whom he was warmly recommended by the abbé Very, a mutual

friend. His appointment met with general approval, and was hailed with

enthusiasm by the philosophes.

A month later (24 August) he was appointed controller-general. His

first act was to submit to the king a statement of his guiding

principles: "No bankruptcy, no increase of taxation, no borrowing."

Turgot's policy, in face of the desperate financial position, was to

enforce the most rigid economy in all departments. All departmental

expenses were to be submitted for the approval of the

controller-general, a number of sinecures were suppressed, the holders of them being compensated, and the abuse of the acquits au comptant was

attacked, while Turgot appealed personally to the king against the

lavish giving of places and pensions. He also contemplated a

thorough-going reform of the Ferme Générale,

but contented himself, as a beginning, with imposing certain conditions

on the leases as they were renewed—such as a more efficient personnel,

and the abolition for the future of the abuse of the croupes (the

name given to a class of pensions), a reform which Terray had shirked

on finding how many persons in high places were interested in them, and

annulling certain leases, such as those of the manufacture of gunpowder

and the administration of the royal mails, the former of which was

handed over to a company with the scientist Lavoisier as one of its advisers, and the latter superseded by a quicker and more comfortable service of diligences which were nicknamed "turgotines".

He also prepared a regular budget. Turgot's measures succeeded in

considerably reducing the deficit, and raised the national credit to

such an extent that in 1776, just before his fall, he was able to

negotiate a loan with some Dutch bankers

at 4%; but the deficit was still so large as to prevent him from

attempting at once to realize his favourite scheme of substituting for

indirect taxation a single tax on land. He suppressed, however, a number of octrois and minor duties, and opposed, on grounds of economy, the participation of France in the American Revolutionary War, though without success. Turgot

at once set to work to establish free trade in grain, but his edict,

which was signed on 13 September 1774, met with strong opposition even

in the conseil du roi. A striking feature was the preamble, setting forth the doctrines on which the edict was based, which won the praise of the philosophes and

the ridicule of the wits; this Turgot rewrote three times, it is said,

in order to make it "so clear that any village judge could explain it

to the peasants." The opposition to the edict was strong. Turgot was

hated by those who had been interested in the speculations in grain

under the regime of the abbé Terray, among whom were included

some of the princes of the blood. Moreover, the commerce des blés had been a favourite topic of the salons for some years past, and the witty Galiani, the opponent of the physiocrats, had a large following. The opposition was now continued by Linguet and by Necker, who in 1775 published his Essai sur la législation et le commerce des grains.

But Turgot's worst enemy was the poor harvest of 1774, which led to a

slight rise in the price of bread in the winter and early spring of

1774 - 1775. In April disturbances arose at Dijon, and early in May there occurred those extraordinary bread-riots known as the guerre des farines, which may be looked upon as a first sample of the French Revolution,

so carefully were they organized. Turgot showed great firmness and

decision in repressing the riots, and was loyally supported by the king

throughout. His position was strengthened by the entry of Malesherbes into the ministry (July 1775). All this time Turgot had been preparing his famous Six Edicts, which were finally presented to the conseil du roi (January

1776). Of the six edicts four were of minor importance, but the two

which met with violent opposition were, firstly, the edict suppressing

the corvées, and secondly, that suppressing the jurandes and maîtrises, by which the craft guilds maintained

their privileges. In the preamble to the former Turgot boldly announced

as his object the abolition of privilege, and the subjection of all

three Estates of the realm to taxation; the clergy were afterwards excepted, at the request of Maurepas. In the preamble to the edict on the jurandes he

laid down as a principle the right of every man to work without

restriction. He obtained the registration of the edicts by the lit de justice of

12 March, but by that time he had nearly everybody against him. His

attacks on privilege had won him the hatred of the nobles and the parlements ; his attempted reforms in the royal household, that of the court; his free trade legislation, that of the financiers ; his views on tolerance and his agitation for the suppression of the phrase that was offensive to Protestants in the king's coronation oath, that of the clergy; and his edict on the jurandes, that of the rich bourgeoisie of Paris and others, such as the prince de Conti, whose interests were involved. The queen disliked him for opposing the grant of favours to her proteges, and he had offended Mme. de Polignac in a similar manner. All

might yet have gone well if Turgot could have retained the confidence

of the king, but the king could not fail to see that Turgot had not the

support of the other ministers. Even his friend Malesherbes thought he

was too rash, and was, moreover, himself discouraged and wished to

resign. The alienation of Maurepas was also increasing. Whether through

jealousy of the ascendancy which

Turgot had acquired over the king, or through the natural

incompatibility of their characters, he was already inclined to take

sides against Turgot, and the reconciliation between him and the queen,

which took place about this time, meant that he was henceforth the tool

of the Polignac clique and the Choiseul party. About this time, too, appeared a pamphlet, Le Songe de M. Maurepas, generally ascribed to the comte de Provence (Louis XVIII), containing a bitter caricature of Turgot. Before

relating the circumstances of Turgot's fall we may briefly resume his

views on the administrative system. With the physiocrats, he believed

in an enlightened political absolutism,

and looked to the king to carry through all reforms. As to the

parlements, he opposed all interference on their part in legislation,

considering that they had no competency outside the sphere of justice.

He recognized the danger of the recap of the old parlement, but was

unable effectively to oppose it since he had been associated with the

dismissal of Maupeou and Terray, and seems to have underestimated its power. He was opposed to the summoning of the Estates-general advocated

by Malesherbes (6 May 1775), possibly on the grounds that the two

privileged orders would have too much power in them. His own plan is to

be found in his Mémoire sur les municipalités, which was submitted informally to the king. In Turgot's proposed system, landed proprietors alone were to form the electorate,

no distinction being made among the three orders; the members of the

town and country municipalités were to elect representatives for

the district municipalités, which in turn would elect to the

provincial municipalités, and the latter to a grande

municipalité, which should have no legislative powers, but

should concern itself entirely with the administration of taxation.

With this was to be combined a whole system of education, relief of the

poor, etc. Louis XVI recoiled from this as being too great a leap in

the dark, and such a fundamental difference of opinion between king and

minister was bound to lead to a breach sooner or later. Turgot's only

choice, however, was between "tinkering" at the existing system in

detail and a complete revolution, and his attack on privilege, which

might have been carried through by a popular minister and a strong

king, was bound to form part of any effective scheme of reform.

As

minister of the navy from 1774 to 1776, he opposed financial support

for the American Revolution. He believed in the virtue and inevitable

success of the revolution but warned that France could neither

financially nor socially afford to overtly aid it. French intellectuals

saw America as the hope of mankind and magnified American virtues to

demonstrate the validity of their ideals. Turgot, however, emphasized

what he believed were American inadequacies. He complained that the new

American state constitutions failed to adopt the physiocratic principle

of distinguishing for purposes of taxation between those who owned land

and those who did not, the principle of direct taxation of property

holders had not been followed, and a complicated legal and

administrative structure had been created to regulate commerce. On the

social level, Turgot and the philosophes suffered further

disappointment: a religious oath was required of elected officials and

slavery was not abolished. Turgot died in 1781 before the conclusion of

the war. Although disappointed, Turgot never doubted positive evolution. The

immediate cause of Turgot's fall is uncertain. Some speak of a plot, of

forged letters containing attacks on the queen shown to the king as

Turgot's, of a series of notes on Turgot's budget prepared, it is said,

by Necker,

and shown to the king to prove his incapacity. Others attribute it to

the queen, and there is no doubt that she hated Turgot for supporting Vergennes in demanding the recall of the comte de Guînes, the ambassador in London,

whose cause she had ardently espoused at the prompting of the Choiseul

clique. Others attribute it to an intrigue of Maurepas. On the

resignation of Malesherbes (April 1776), whom Turgot wished to replace by the abbé Very, Maurepas proposed to the king as his successor a nonentity named

Amelot. Turgot, on hearing of this, wrote an indignant letter to the

king, in which he reproached him for refusing to see him, pointed out

in strong terms the dangers of a weak ministry and a weak king, and

complained bitterly of Maurepas's irresolution and subjection to court

intrigues; this letter the king, though asked to treat it as

confidential, is said to have shown to Maurepas, whose dislike for

Turgot it still further embittered. With all these enemies, Turgot's

fall was certain, but he wished to stay in office long enough to finish

his project for the reform of the royal household before resigning. To

his dismay, he was not allowed to do, and on 12 May was ordered to send

in his resignation. He at once retired to La Roche-Guyon,

the château of the duchesse d'Enville, returning shortly to

Paris, where he spent the rest of his life in scientific and literary

studies, being made vice-president of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in 1777. In

character Turgot was simple, honourable and upright, with a passion for

justice and truth. He was an idealist, his enemies would say a doctrinaire,

and certainly the terms "natural rights," "natural law," frequently

occur in his writings. His friends speak of his charm and gaiety in

intimate intercourse, but among strangers he was silent and awkward,

and produced the impression of being reserved and disdainful. On one

point both friends and enemies agree, and that is his brusquerie and his lack of tact in the management of men; August Oncken points

out with some reason the schoolmasterish tone of his letters, even to

the king. As a statesman he has been very variously estimated, but it

is generally agreed that a large number of the reforms and ideas of the

Revolution were due to him; the ideas did not as a rule originate with

him, but it was he who first gave them prominence. As to his position

as an economist, opinion is also divided. Oncken, to take the extreme

of condemnation, looks upon him as a bad physiocrat and a confused

thinker, while Leon Say considers

that he was the founder of modern political economy, and that "though

he failed in the 18th century he triumphed in the 19th."