<Back to Index>

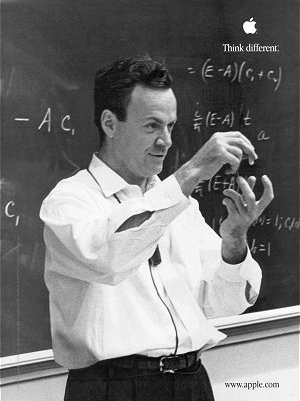

- Physicist Richard Phillips Feynman, 1918

- Painter Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1824

- US Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Jr., 1891

Richard Phillips Feynman (May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American physicist known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics and the physics of the superfluidity of supercooled liquid helium, as well as in particle physics (he proposed the parton model). For his contributions to the development of quantum electrodynamics, Feynman, jointly with Julian Schwinger and Sin-Itiro Tomonaga, received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965. He developed a widely used pictorial representation scheme for the mathematical expressions governing the behavior of subatomic particles, which later became known as Feynman diagrams. During his lifetime, Feynman became one of the best-known scientists in the world.

He assisted in the development of the atomic bomb and was a member of the panel that investigated the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster. In addition to his work in theoretical physics, Feynman has been credited with pioneering the field of quantum computing, and introducing the concept of nanotechnology (creation of devices at the molecular scale). He held the Richard Chace Tolman professorship in theoretical physics at the California Institute of Technology.

Feynman was a keen popularizer of physics through both books and lectures, notably a 1959 talk on top-down nanotechnology called There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom and The Feynman Lectures on Physics. Feynman also became known through his semi-autobiographical books (Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman! and What Do You Care What Other People Think?) and books written about him, such as Tuva or Bust! He was regarded as an eccentric and free spirit. He was a prankster, juggler, safecracker, proud amateur painter, and bongo player. He liked to pursue a variety of seemingly unrelated interests, such as art, percussion, Maya hieroglyphs, and lock picking. Feynman also had a deep interest in biology, and was a friend of the geneticist and microbiologist Esther Lederberg, who developed replica plating and discovered bacteriophage lambda. They had several mutual physicist friends who, after beginning their careers in nuclear research, moved for moral reasons into genetics, among them Leó Szilárd, Guido Pontecorvo, and Aaron Novick.

Richard Phillips Feynman was born on May 11, 1918, in Far Rockaway, Queens, New York. His family originated from Russia and Poland; both of his parents were Jewish, but they were not devout. Feynman (in common with the famous physicists Edward Teller and Albert Einstein) was a late talker;

by his third birthday he had yet to utter a single word. The young

Feynman was heavily influenced by his father, Melville, who encouraged

him to ask questions to challenge orthodox thinking. From his mother,

Lucille, he gained the sense of humor that he had throughout his life.

As a child, he delighted in repairing radios and had a talent for engineering. His sister Joan also became a professional physicist. In high school, his IQ was determined to be 125: high, but "merely respectable" according to biographer Gleick. He would later scoff at psychometric testing. By 15, he had learned differential and integral calculus. Before entering college, he was experimenting with and re-creating mathematical topics, such as the half-derivative, utilizing his own notation. In high school, he was developing the mathematical intuition behind his Taylor series of mathematical operators. His

habit of direct characterization would sometimes rattle more

conventional thinkers; for example, one of his questions when learning

feline anatomy was "Do you have a map of the cat?" (referring to an

anatomical chart). Feynman attended Far Rockaway High School, a school that also produced fellow laureates Burton Richter and Baruch Samuel Blumberg. A

member of the Arista Honor Society, in his last year in high school,

Feynman won the New York University Math Championship; the large

difference between his score and those of his closest competitors

shocked the judges. He applied to Columbia University, but was not accepted. Instead he attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he received a bachelor's degree in 1939, and in the same year was named a Putnam Fellow. While there, Feynman took every physics course offered, including a graduate course on theoretical physics while only in his second year. He obtained a perfect score on the graduate school entrance exams to Princeton University in mathematics and physics — an unprecedented feat — but did rather poorly on the history and English portions. Attendees at Feynman's first seminar included Albert Einstein, Wolfgang Pauli, and John von Neumann. He received a Ph.D. from Princeton in 1942; his thesis advisor was John Archibald Wheeler. Feynman's thesis applied the principle of stationary action to

problems of quantum mechanics, laying the ground work for the "path

integral" approach and Feynman diagrams, and was entitled "The

Principle of Least Action in Quantum Mechanics". At Princeton, the physicist Robert R. Wilson encouraged Feynman to participate in the Manhattan Project — the wartime U.S. Army project at Los Alamos developing the atomic bomb. Feynman said he was persuaded to join this effort to build it before Nazi Germany. He was assigned to Hans Bethe's

theoretical division, and impressed Bethe enough to be made a group

leader. He and Bethe developed the Bethe-Feynman formula for

calculating the yield of a fission bomb, which built upon previous work

by Robert Serber. Feynman was sought out by physicist Niels Bohr for

one-on-one discussions. He later discovered the reason: most physicists

were too in awe of Bohr to argue with him. Feynman had no such

inhibitions, vigorously pointing out anything he considered to be

flawed in Bohr's thinking. Feynman said he felt as much respect for

Bohr as anyone else, but once anyone got him talking about physics, he

would become so focused he forgot about social niceties. Due to the top secret nature of the work, Los Alamos was isolated. In Feynman's own words, "There wasn't anything to do there".

Bored, he indulged his curiosity by learning to pick the combination

locks on cabinets and desks used to secure papers. Feynman played many

jokes on colleagues. In one case he found the combination to a locked

filing cabinet by trying the numbers a physicist would use (it proved

to be 27-18-28 after the base of natural logarithms, e = 2.71828...), and found that the three filing cabinets where a colleague kept a set of atomic bomb research

notes all had the same combination. He left a series of notes as a

prank, which initially spooked his colleague, Frederic de Hoffman, into

thinking a spy or saboteur had gained access to atomic bomb secrets. On

several occasions, Feynman drove to Albuquerque to see his ailing wife

in a car borrowed from Klaus Fuchs, who was later discovered to be a real spy for the Soviets, transporting nuclear secrets in his car to Albuquerque. On occasion, Feynman would find an isolated section of the mesa to drum in the style of American natives;

"and maybe I would dance and chant, a little". These antics did not go

unnoticed, and rumors spread about a mysterious Indian drummer called

"Injun Joe". He also became a friend of laboratory head J. Robert Oppenheimer, who unsuccessfully tried to court him away from his other commitments after the war to work at the University of California, Berkeley. Feynman alludes to his thoughts on the justification for getting involved in the Manhattan project in The Pleasure of Finding Things Out.

As mentioned earlier, he felt the possibility of Nazi Germany

developing the bomb before the Allies was a compelling reason to help

with its development for the US. However, he goes on to say that it was

an error on his part not to reconsider the situation when Germany was

defeated. In the same publication, Feynman also talks about his worries

in the atomic bomb age, feeling for some considerable time that there

was a high risk that the bomb would be used again soon so that it was

pointless to build for the future. Later he describes this period as a

"depression." Following

the completion of his Ph.D. in 1942, Feynman held an appointment at the

University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW) as an assistant professor of

physics. The appointment was spent on leave for his involvement in the

Manhattan project. In 1945, he received a letter from Dean Mark

Ingraham of the College of Letters and Science requesting his return to

UW to teach in the coming academic year. His appointment was not

extended when he did not commit to return. In a talk given several

years later at UW, Feynman quipped, "It's great to be back at the only

University that ever had the good sense to fire me". After the war, Feynman declined an offer from the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, despite the presence there of such distinguished faculty members as Albert Einstein, Kurt Gödel, and John von Neumann. Feynman followed Hans Bethe, instead, to Cornell University, where Feynman taught theoretical physics from 1945 to 1950. During a temporary depression following the destruction of Hiroshima by

the bomb produced by the Manhattan Project, he focused on complex

physics problems, not for utility, but for self-satisfaction. One of

these was analyzing the physics of a twirling, nutating dish

as it is moving through the air. His work during this period, which

used equations of rotation to express various spinning speeds, would

soon prove important to his Nobel Prize-winning work. Yet because he

felt burned out, and had turned his attention to less immediately

practical but more entertaining problems, he felt surprised by the

offers of professorships from renowned universities. Despite

yet another offer from the Institute for Advanced Study, which would

have included teaching duties (one of his reasons for rejecting the

Institute's initial offer), Feynman opted for the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) — as he says in his book Surely You're Joking Mr. Feynman! —

because a desire to live in a mild climate had firmly fixed itself in

his mind while installing tire chains on his car in the middle of a

snowstorm in Ithaca. Feynman has been called the "Great Explainer". He

gained a reputation for taking great care when giving explanations to

his students and for making it a moral duty to make the topic

accessible. His guiding principle was that if a topic could not be

explained in a freshman lecture, it was not yet fully understood. Feynman gained great pleasure from coming up with such a "freshman-level" explanation, for example, of the connection between spin and

statistics. What he said was that groups of particles with spin 1/2

"repel", whereas groups with integer spin "clump". This was a

brilliantly simplified way of demonstrating how Fermi-Dirac statistics and Bose-Einstein statistics evolved as a consequence of studying how fermions and bosons behave

under a rotation of 360°. This was also a question he pondered in

his more advanced lectures and to which he demonstrated the solution in

the 1986 Dirac memorial lecture. In

the same lecture, he further explained that antiparticles must exist,

for if particles only had positive energies, they would not be

restricted to a so-called "light cone". He

opposed rote learning or unthinking memorization and other teaching

methods that emphasized form over function. He put these opinions into

action whenever he could, from a conference on education in Brazil to a

State Commission on school textbook selection. Clear thinking and clear presentation were

fundamental prerequisites for his attention. It could be perilous even

to approach him when unprepared, and he did not forget the fools or

pretenders. Feynman did significant work while at Caltech, including research in: He also developed Feynman diagrams, a bookkeeping device which helps in conceptualizing and calculating interactions between particles in spacetime, notably the interactions between electrons and their antimatter counterparts, positrons.

This device allowed him, and later others, to approach time

reversibility and other fundamental processes. From his diagrams of a small number of particles interacting in spacetime, Feynman could then model all of physics in terms of those particles' spins and the range of coupling of the fundamental forces. Feynman attempted an explanation of the strong interactions governing nucleons scattering called the parton model. The parton model emerged as a complement to the quark model developed by his Caltech colleague Murray Gell-Mann. The relationship

between the two models was murky; Gell-Mann referred to Feynman's

partons derisively as "put-ons". In the mid 1960s, physicists believed

that quarks were just a bookkeeping device for symmetry numbers, not

real particles, as the statistics of the Omega-minus particle,

if it were interpreted as three identical strange quarks bound

together, seemed impossible if quarks were real. The Stanford linear

accelerator deep inelastic scattering experiments of the late 1960s showed, analogously to Ernest Rutherford's experiment of scattering alpha particles on gold nuclei in 1911, that nucleons (protons

and neutrons) contained point-like particles which scattered electrons.

It was natural to identify these with quarks, but Feynman's parton

model attempted to interpret the experimental data in a way which did

not introduce additional hypotheses. For example, the data showed that

some 45% of the energy momentum was carried by electrically neutral

particles in the nucleon. These electrically neutral particles are now

seen to be the gluons which

carry the forces between the quarks and carry also the three-valued

color quantum number which solves the Omega - problem. Feynman did not

dispute the quark model; for example, when the fifth quark was

discovered in 1977, Feynman immediately pointed out to his students

that the discovery implied the existence of a sixth quark, which was

duly discovered in the decade after his death. After the success of quantum electrodynamics, Feynman turned to quantum gravity.

By analogy with the photon, which has spin 1, he investigated the

consequences of a free massless spin 2 field, and was able to derive the Einstein field equation of general relativity. In 1965, Feynman was appointed a foreign member of the Royal Society. At

this time in the early 1960s, Feynman exhausted himself by working on

multiple major projects at the same time, including a request, while at

Caltech, to "spruce up" the teaching of undergraduates. After three

years devoted to the task, he produced a series of lectures that would

eventually become the Feynman Lectures on Physics,

one reason that Feynman is still regarded as one of the greatest

teachers of physics. He wanted a picture of a drumhead sprinkled with

powder to show the modes of vibration at the beginning of the book.

Outraged by many rock and roll and drug connections that could be made

from the image, the publishers changed the cover to plain red, though

they included a picture of him playing drums in the foreword. Feynman

later won the Oersted Medal for teaching, of which he seemed especially proud. His

students competed keenly for his attention; he was once awakened when a

student solved a problem and dropped it in his mailbox; glimpsing the

student sneaking across his lawn, he could not go back to sleep, and he

read the student's solution. The next morning his breakfast was

interrupted by another triumphant student, but Feynman informed him

that he was too late. Partly

as a way to bring publicity to progress in physics, Feynman offered

$1000 prizes for two of his challenges in nanotechnology, claimed by William McLellan and Tom Newman, respectively. He was also one of the first scientists to conceive the possibility of quantum computers. Many of his lectures and other miscellaneous talks were turned into books, including The Character of Physical Law and QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter. He gave lectures which his students annotated into books, such as Statistical Mechanics and Lectures on Gravity. The Feynman Lectures on Physics occupied two physicists, Robert B. Leighton and Matthew Sands as

part-time co-authors for several years. Even though they were not

adopted by most universities as textbooks, the books continue to be

bestsellers because they provide a deep understanding of physics. As of

2005, The Feynman Lectures on Physics has

sold over 1.5 million copies in English, an estimated 1 million copies

in Russian, and an estimated half million copies in other languages. In 1974, Feynman delivered the Caltech commencement address on the topic of cargo cult science, which has the semblance of science but is only pseudoscience due

to a lack of "a kind of scientific integrity, a principle of scientific

thought that corresponds to a kind of utter honesty" on the part of the

scientist. He instructed the graduating class that "The first principle

is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to

fool. So you have to be very careful about that. After you've not

fooled yourself, it's easy not to fool other scientists. You just have

to be honest in a conventional way after that." In

1984-86, he developed a variational method for the approximate

calculation of path integrals which has led to a powerful method of

converting divergent perturbation expansions into convergent

strong-coupling expansions (Variational perturbation theory) and, as a consequence, to the most accurate determination of critical exponents measured in satellite experiments. In the late 1980s, according to "Richard Feynman and the Connection Machine", Feynman played a crucial role in developing the first massively parallel computer, and in finding innovative uses for it in numerical computations, in building neural networks, as well as physical simulations using cellular automata (such as turbulent fluid flow), working with Stephen Wolfram at Caltech. His son Carl also

played a role in the development of the original Connection Machine

engineering; Feynman influencing the interconnects while his son worked

on the software. Feynman diagrams are now fundamental for string theory and M-theory, and have even been extended topologically. The world-lines of the diagrams have developed to become tubes to allow better modeling of more complicated objects such as strings and membranes. However, shortly before his death, Feynman criticized string theory in

an interview: "I don't like that they're not calculating anything," he

said. "I don't like that they don't check their ideas. I don't like

that for anything that disagrees with an experiment, they cook up an

explanation—a fix-up to say, 'Well, it still might be true.'" These

words have since been much-quoted by opponents of the string-theoretic

direction for particle physics. Feynman was requested to serve on the Presidential Rogers Commission which investigated the Challenger disaster of 1986, where he played an important role. Feynman devoted the latter half of his book What Do You Care What Other People Think? to

his experience on the Rogers Commission, straying from his usual

convention of brief, light-hearted anecdotes to deliver an extended and

sober narrative. Feynman's account reveals a disconnect between NASA's

engineers and executives that was far more striking than he expected.

His interviews of NASA's high-ranking managers revealed startling

misunderstandings of elementary concepts. He concluded that the NASA

management's space shuttle reliability estimate was fantastically

unrealistic. He warned in his appendix to the commission's report, "For

a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public

relations, for nature cannot be fooled." While researching for his Ph.D., Feynman married his first wife, Arline Greenbaum (often spelled Arlene). She was diagnosed with tuberculosis,

but she and Feynman were careful, and he never contracted it. She

succumbed to the disease in 1945. He was married a second time in June 1952, to Mary Louise Bell of Neodesha, Kansas; this marriage was brief and unsuccessful. He later married Gweneth Howarth from Ripponden, Yorkshire, who shared his enthusiasm for life and spirited adventure. Besides their home in Altadena, California, they had a beach house in Baja California,

purchased with the prize money from Feynman's Nobel Prize, his one

third share of $55,000. They remained married until Feynman's death.

They had a son, Carl, in 1962, and adopted a daughter, Michelle, in

1968. According to Genius, the James Gleick-authored biography, Feynman experimented with LSD during his professorship at Caltech. Somewhat

embarrassed by his actions, Feynman largely sidestepped the issue when

dictating his anecdotes; he mentions it in passing in the "O Americano,

Outra Vez" section, while the "Altered States" chapter in Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman! describes only marijuana and ketamine experiences at John Lilly's famed sensory deprivation tanks, as a way of studying consciousness. Feynman

gave up alcohol when he began to show early signs of alcoholism, as he

did not want to do anything that could damage his brain—the same reason

given in "O Americano, Outra Vez" for his reluctance to experiment with

LSD.

He immersed himself in work on the project, and was present at the Trinity bomb

test. Feynman claimed to be the only person to see the explosion

without the very dark glasses provided, reasoning that it was safe to

look through a truck windshield, as it would screen out the harmful ultraviolet radiation. As

a junior physicist, he was not central to the project. The greater part

of his work was administering the computation group of human computers in the Theoretical division (one of his students there, John G. Kemeny, would later go on to co-write the computer language BASIC). Later, with Nicholas Metropolis, he assisted in establishing the system for using IBM punch cards for

computation. Feynman succeeded in solving one of the equations for the

project that were posted on the blackboards. However, they did not "do

the physics right" and Feynman's solution was not used. Feynman's other work at Los Alamos included calculating neutron equations for the Los Alamos "Water Boiler", a small nuclear reactor, to measure how close an assembly of fissile material was to criticality. On completing this work he was transferred to the Oak Ridge facility, where he aided engineers in devising safety procedures for material storage so that criticality accidents (for

example, due to sub-critical amounts of fissile material inadvertently

stored in proximity on opposite sides of a wall) could be avoided. He

also did theoretical work and calculations on the proposed uranium-hydride bomb, which later proved not to be feasible.