<Back to Index>

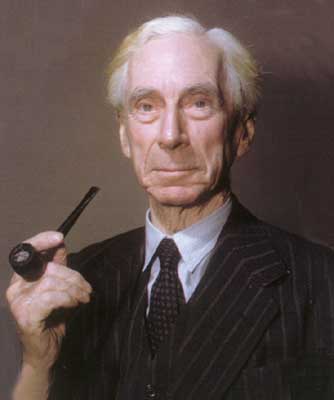

- Philosopher and Logician Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 1872

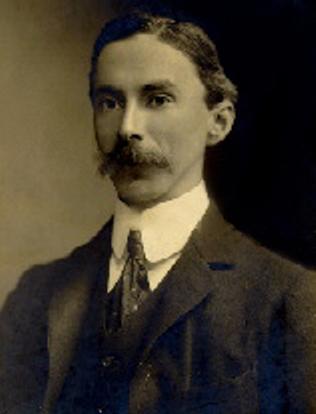

- Architect Walter Adolph Georg Gropius, 1883

- Emperor and Autocrat of all the Russias Nicholas II, 1868

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, OM, FRS (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, socialist, pacifist and social critic. Although he spent most of his life in England, he was born in Wales, where he also died.

Russell led the British "revolt against idealism" in the early 1900s. He is considered one of the founders of analytic philosophy along with his protégé Wittgenstein and his elder Frege, and is widely held to be one of the 20th century's premier logicians. He co-authored, with A. N. Whitehead, Principia Mathematica, an attempt to ground mathematics on logic. His philosophical essay "On Denoting" has been considered a "paradigm of philosophy." Both works have had a considerable influence on logic, mathematics, set theory, linguistics, and philosophy. He was a prominent anti-war activist, championing free trade between nations and anti-imperialism. Russell was imprisoned for his pacifist activism during World War I, campaigned against Adolf Hitler, for nuclear disarmament, criticised Soviet totalitarianism and the United States of America's involvement in the Vietnam War. In 1950, Russell was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, "in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought."

Bertrand Russell was born on 18 May 1872 at Cleddon Hall, Trellech, Monmouthshire, Wales, into a liberal family of the British aristocracy. His paternal grandfather, John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, was the third son of John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford, and had twice been asked by Queen Victoria to form a government, serving her as Prime Minister in the 1840s and 1860s. The

Russells had been prominent in England for several centuries before

this, coming to power and the peerage with the rise of the Tudor dynasty. They established themselves as one of Britain's leading Whig (Liberal) families, and participated in every great political event from the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536–40 to the Glorious Revolution in 1688–89 to the Great Reform Act in 1832. Russell's mother Katherine Louisa (1844–1874) was the daughter of Edward Stanley, 2nd Baron Stanley of Alderley, and was the sister of Rosalind Howard, Countess of Carlisle. Russell's parents were radical for their times. Russell's father, Viscount Amberley, was an atheist and consented to his wife's affair with their children's tutor, the biologist Douglas Spalding. Both were early advocates of birth control at a time when this was considered scandalous. John Russell's atheism was evident when he asked the philosopher John Stuart Mill to act as Russell's secular godfather. Mill died the year after Russell's birth, but his writings had a great effect on Russell's life. Russell had two siblings: Frank (nearly seven years older than Bertrand), and Rachel (four years older). In June 1874 Russell's mother died of diphtheria, followed shortly by Rachel's death. In January 1876, his father also died after bronchitis following a long period of depression. Frank and Bertrand were placed in the care of their staunchly Victorian grandparents, who lived at Pembroke Lodge in Richmond Park. John Russell, 1st Earl Russell,

his grandfather, died in 1878, and was remembered by Russell as a

kindly old man in a wheelchair. As a result, his widow, the Countess

Russell (née Lady Frances Elliot), was the dominant family

figure for the rest of Russell's childhood and youth. The countess was from a Scottish Presbyterian family, and successfully petitioned a British court to set aside a provision in Amberley's will requiring the children to be raised as agnostics. Despite her religious conservatism, she held progressive views in other areas (accepting Darwinism and supporting Irish Home Rule), and her influence on Bertrand Russell's outlook on social justice and

standing up for principle remained with him throughout his life —

her favourite Bible verse, 'Thou shalt not follow a multitude to do

evil' (Exodus 23:2),

became his motto. The atmosphere at Pembroke Lodge was one of frequent

prayer, emotional repression and formality; Frank reacted to this with

open rebellion, but the young Bertrand learned to hide his feelings. Russell's adolescence was very lonely, and he often contemplated suicide.

He remarked in his autobiography that his keenest interests were in

sex, religion and mathematics, and that only the wish to know more

mathematics kept him from suicide. He was educated at home by a series of tutors. His brother Frank introduced him to the work of Euclid, which transformed Russell's life. Also, during these formative years, he discovered the works of Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Russell claimed that beginning at age 15, he spent considerable time thinking about the validity of Christian religious dogma, and by 18 had decided to discard the last of it. Russell won a scholarship to read for the Mathematical Tripos at Trinity College, Cambridge, and commenced his studies there in 1890. He became acquainted with the younger G.E. Moore and came under the influence of Alfred North Whitehead, who recommended him to the Cambridge Apostles.

He quickly distinguished himself in mathematics and philosophy,

graduating with a B.A. in the former subject in 1893 and adding a

fellowship in the latter in 1895. Russell first met the American Quaker Alys Pearsall Smith when

he was seventeen years old. He became a friend of the Pearsall Smith

family—they knew him primarily as 'Lord John's grandson' and enjoyed

showing him off—and travelled with them to the continent; it was in

their company that Russell visited the Paris Exhibition of 1889 and was able to climb the Eiffel Tower soon after it was completed. He soon fell in love with the puritanical, high-minded Alys, who was a graduate of Bryn Mawr College near Philadelphia, and, contrary to his grandmother's wishes, he married her on 13 December 1894. Their marriage began

to fall apart in 1901 when it occurred to Russell, while he was out on

his bicycle, that he no longer loved her. She asked him if he loved her

and he replied that he didn't. Russell also disliked Alys's mother,

finding her controlling and cruel. It was to be a hollow shell of a

marriage and they finally divorced in 1921, after a lengthy period of

separation. During this period, Russell had passionate (and often simultaneous) affairs with a number of women, including Lady Ottoline Morrell and the actress Lady Constance Malleson. Russell began his published work in 1896 with German Social Democracy,

a study in politics that was an early indication of a lifelong interest

in political and social theory. In 1896, he taught German social

democracy at the London School of Economics, where he also lectured on the science of power in the autumn of 1937. He was also a member of the Coefficients dining club of social reformers set up in 1902 by the Fabian campaigners Sidney and Beatrice Webb. In 1905 he wrote the essay "On Denoting", which was published in the philosophical journal Mind. Russell became a fellow of the Royal Society in 1908. The first of three volumes of Principia Mathematica, written with Whitehead, was published in 1910, which, along with the earlier The Principles of Mathematics, soon made Russell world famous in his field. In 1911, he became acquainted with the Austrian engineering student Ludwig Wittgenstein,

whom he viewed as a genius and a successor, who would continue his work

on logic. He spent hours dealing with Wittgenstein's various phobias

and his frequent bouts of despair. This was often a drain on Russell's

energy, but Russell continued to be fascinated by him and encouraged his academic development, including the publication of Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus in 1922.

During the First World War, Russell was one of a very small number of intellectuals engaged in pacifist activities, and, in 1916, he was dismissed from Trinity College following his conviction under the Defence of the Realm Act. A later conviction resulted in six months' imprisonment in Brixton prison. Russell was released from prison in September 1918. In

August 1920, Russell traveled to Russia as part of an official

delegation sent by the British government to investigate the effects of

the Russian Revolution. He met Lenin and

had an hour-long conversation with him. In his autobiography, he

mentions that he found Lenin rather disappointing, and that he sensed

an "impish cruelty" in him. He also cruised down the Volga on a

steam-ship. Russell's lover Dora Black also

visited Russia independently at the same time — she was

enthusiastic about the revolution, but Russell's experiences destroyed

his previous tentative support for it. Russell

subsequently lectured in Beijing on philosophy for one year,

accompanied by Dora. He went there with optimism and hope as China was

then on a new path, among other scholars was Rabindranath Tagore, the

Indian poet and also a Nobel Laureate. While in China, Russell became gravely ill with pneumonia, and incorrect reports of his death were published in the Japanese press. When

the couple visited Japan on their return journey, Dora notified the

world that "Mr. Bertrand Russell, having died according to the Japanese

press, is unable to give interviews to Japanese journalists." The press

were not amused and did not appreciate the sarcasm. On

the couple's return to England on 26 August 1921, Dora was six months

pregnant, and Russell arranged a hasty divorce from Alys, marrying Dora

six days after the divorce was finalised, on 27 September 1921. Russell supported

himself during this time by writing popular books explaining matters of physics, ethics, and education to the layman. Some have suggested that at this point he had an affair with Vivienne Haigh-Wood, first wife of T. S. Eliot. Together

with Dora, he also founded the experimental Beacon Hill School in 1927.

The school was run from a succession of different locations, including

its original premises at the Russell's residence, Telegraph House, near Harting, West Sussex. After he left the school in 1932, Dora continued it until 1943. Russell's

marriage to Dora grew increasingly tenuous, and it reached a breaking

point over her having two children with an American journalist, Griffin Barry. They separated in 1932 and finally divorced. On 18 January 1936, Russell married his third wife, an Oxford undergraduate named Patricia ("Peter") Spence, who had been his children's governess since the summer of 1930. Russell and Peter had one son, Conrad Sebastian Robert Russell, 5th Earl Russell, who became a prominent historian and one of the leading figures in the Liberal Democrat party.

Russell

opposed rearmament against Nazi Germany, but in 1940 changed his view

that avoiding a full scale world war was more important than defeating

Hitler. He concluded that Adolf Hitler taking over all of Europe would

be a permanent threat to democracy. In 1943, he adopted a stance toward

large-scale warfare, "Relative Political Pacifism": War was always a

great evil, but in some particularly extreme circumstances, it may be

the lesser of two evils. Before the Second World War, Russell taught at the University of Chicago, later moving on to Los Angeles to lecture at the University of California, Los Angeles. He was appointed professor at the City College of New York in

1940, but after a public outcry, the appointment was annulled by a

court judgement: his opinions (especially those relating to sexual morality, detailed in Marriage and Morals ten

years earlier) made him "morally unfit" to teach at the college. The

protest was started by the mother of a student who would not have been

eligible for his graduate-level course in mathematical logic. Many

intellectuals, led by John Dewey, protested against his treatment. Albert Einstein's

often-quoted aphorism that "Great spirits have always encountered

violent opposition from mediocre minds..." originated in his open

letter in support of Russell, during this time. Dewey and Horace M. Kallen edited a collection of articles on the CCNY affair in The Bertrand Russell Case. He soon joined the Barnes Foundation, lecturing to a varied audience on the history of philosophy; these lectures formed the basis of History of Western Philosophy. His relationship with the eccentric Albert C. Barnes soon soured, and he returned to Britain in 1944 to rejoin the faculty of Trinity College. During the 1940s and 1950s, Russell participated in many broadcasts over the BBC, particularly the Third Programme,

on various topical and philosophical subjects. By this time Russell was

world famous outside of academic circles, frequently the subject or

author of magazine and newspaper articles, and was called upon to offer

up opinions on a wide variety of subjects, even mundane ones. En route

to one of his lectures in Trondheim, Russell was one of 24 survivors (among a total of 43 passengers) in a aeroplane crash in Hommelvik in October 1948. History of Western Philosophy (1945) became a best-seller, and provided Russell with a steady income for the remainder of his life. In a speech in 1948 Russell

said that if the USSR's aggression continued, it would be morally worse

to go to war after the USSR possessed an atomic bomb than before they

possessed one, because if the USSR had no bomb the West's victory would

come more swiftly and with fewer casualties than if there were atom

bombs on both sides. At that time, only the USA possessed an atomic

bomb, and the USSR was pursuing an extremely aggressive policy towards

the countries in Eastern Europe which it was absorbing into its sphere of influence. Many understood Russell's comments to mean that Russell approved of a first strike in

a war with the USSR, including Lawson, who was present when Russell

spoke. Others, including Griffin, who obtained a transcript of the

speech, have argued that he was merely explaining the usefulness of

America's atomic arsenal in deterring the USSR from continuing its

domination of Eastern Europe. In the King's Birthday Honours of 9 June 1949, Russell was awarded the Order of Merit, and the following year he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. When he was given the Order of Merit, King George VI was affable but slightly embarrassed at decorating a former jailbird, saying that "You have sometimes behaved in a manner that would not do if generally adopted." Russell merely smiled, but afterwards claimed that the reply "That's right, just like your brother" immediately came to mind. In

1952, Russell was divorced by Peter, with whom he had been very

unhappy. Conrad, Russell's son by Peter, did not see his father between

the time of the divorce and 1968 (at which time his decision to meet

his father caused a permanent breach with his mother). Russell married his fourth wife, Edith Finch, soon after the divorce, on 15 December 1952. They had known each other since 1925, and Edith had taught English at Bryn Mawr College near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

sharing a house for twenty years with Russell's old friend Lucy

Donnelly. Edith remained with him until his death, and, by all

accounts, their marriage was a happy, close, and loving one. Russell's

eldest son, John, suffered from serious mental illness,

which was the source of ongoing disputes between Russell and John's

mother, Russell's former wife, Dora. John's wife Susan was also

mentally ill, and eventually Russell and Edith became the legal

guardians of their three daughters (two of whom were later found to have schizophrenia). In 1962, Russell played a public role in the Cuban Missile Crisis: in an exchange of telegrams with the Soviet Union leader Nikita Khrushchev, Khrushchev warned about the imminence of war.

Russell spent the 1950s and 1960s engaged in various political causes, primarily related to nuclear disarmament and opposing the Vietnam war. The 1955 Russell-Einstein Manifesto was

a document calling for nuclear disarmament and was signed by 11 of the

most prominent nuclear physicists and intellectuals of the time. He wrote a great many letters to world leaders during this period. He was in contact with Lionel Rogosin while the latter was filming his anti-war film Good Times, Wonderful Times in the 1960s. He also became a hero to many of the youthful members of the New Left.

During the 1960s, in particular, Russell became increasingly vocal

about his disapproval of what he felt to be the US government's

near-genocidal policies. In 1963 he became the inaugural recipient of

the Jerusalem Prize, an award for writers concerned with the freedom of the individual in society. In October 1965 he tore up his Labour Party card because he feared the party was going to send soldiers to support the USA in the Vietnam War. Russell published his three-volume autobiography in 1967, 1968, and 1969. On 23 November 1969 he wrote to The Times newspaper saying that the preparation for show trials in Czechoslovakia was "highly alarming". The same month he appealed to Secretary General U Thant of the United Nations to

support an international war crimes commission to investigate alleged

torture and genocide by the USA in South Vietnam. The following month,

he protested to Alexei Kosygin over the expulsion of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn from the Writers Union. On

31 January 1970, Russell issued a statement which condemned Israeli

aggression in the Middle East and called for Israeli withdrawal from

territory occupied in 1967. The statement said that: This was Russell's final political statement or act. It was read out at the International Conference of Parliamentarians in Cairo on 3 February 1970, the day after his death. Russell died of influenza on 2 February 1970 at his home, Plas Penrhyn, in Penrhyndeudraeth, Merionethshire, Wales. He was cremated in Colwyn Bay on

5 February 1970. In accordance with his will there was no religious

ceremony; his ashes were scattered over the Welsh mountains later that

year. At

the age of 84, Russell added a five-paragraph prologue to a new

publication of his autobiography, giving a summary of the work and his

life, titled WHAT I HAVE LIVED FOR. Three

passions, simple but overwhelmingly strong, have governed my life: the

longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the

suffering of mankind. These passions, like great winds, have blown me

hither and thither, in a wayward course, over a deep ocean of anguish,

reaching to the very verge of despair.

I have sought love, first,

because it brings ecstasy—ecstasy so great that I would often have

sacrificed all the rest of life for a few hours of this joy. I have

sought it, next, because it relieves loneliness—that terrible

loneliness in which one shivering consciousness looks over the rim of

the world into the cold unfathomable lifeless abyss. I have sought it,

finally, because in the union of love I have seen, in a mystic

miniature, the prefiguring vision of the heaven that saints and poets

have imagined. This is what I sought, and though it might seem too good

for human life, this is what—at last—I have found.

With equal

passion I have sought knowledge. I have wished to understand the hearts

of men. I have wished to know why the stars shine. And I have tried to

apprehend the Pythagorean power by which number holds sway above the

flux. A little of this, but not much, I have achieved.

Love and

knowledge, so far as they were possible, led upward toward the heavens.

But always pity brought me back to earth. Echoes of cries of pain

reverberate in my heart. Children in famine, victims tortured by

oppressors, helpless old people a hated burden to their sons, and the

whole world of loneliness, poverty, and pain make a mockery of what

human life should be. I long to alleviate the evil, but I cannot, and I

too suffer.

This has been my life. I have found it worth living, and would gladly live it again if the chance were offered me.