<Back to Index>

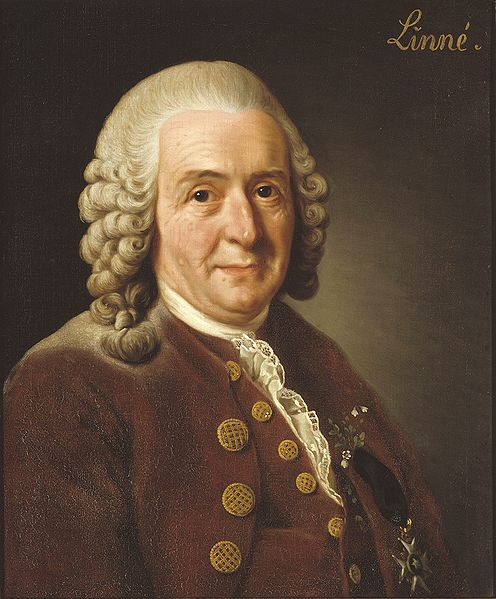

- Botanist and Zoologist Carl Linnaeus, 1707

- Architect Sir Charles Barry, 1795

- President of Brazil Epitácio Lindolfo da Silva Pessoa, 1865

Carl Linnaeus (Latinized as Carolus Linnaeus, also known after his ennoblement as Carl von Linné, 23 May [O.S. 12 May] 1707 – 10 January 1778) was a Swedish botanist, physician, and zoologist, who laid the foundations for the modern scheme of binomial nomenclature. He is known as the father of modern taxonomy, and is also considered one of the fathers of modern ecology.

Linnaeus was born in the countryside of Småland, in southern Sweden. His father was the first in his ancestry to adopt a permanent last name; prior to that, ancestors had used the patronymic naming system of Scandinavian countries. His father adopted the Latin-form name Linnaeus after a giant linden tree on the family homestead. Linnaeus got most of his higher education at Uppsala University and began giving lectures on botany there in 1730. He lived abroad between 1735–1738, where he studied and also published a first edition of his Systema Naturae in the Netherlands. He then returned to Sweden where he became professor of botany at Uppsala. In the 1740s, he was sent on several journeys through Sweden to find and classify plants and animals. In the 1750s and 60s, he continued to collect and classify animals, plants, and minerals, and published several volumes. At the time of his death, he was widely renowned throughout Europe as one of the most acclaimed scientists of the time.

The Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau sent him the message: "Tell him I know no greater man on earth." The German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote: "With the exception of Shakespeare and Spinoza, I know no one among the no longer living who has influenced me more strongly." Swedish author August Strindberg wrote: "Linnaeus was in reality a poet who happened to become a naturalist".

In botany, the author abbreviation used to indicate Linnaeus as the authority for species names is simply L. In

Linnaeus' time, most Swedes had no family names. Linnaeus' grandfather

was named Ingemar Bengtsson. Ingemar's surname was Bengtsson, i.e. son

of Bengt, following the long-standing Scandinavian tradition of sons

bearing, as surnames, their fathers' given names with -son appended;

Linnaeus' father was known as Nils Ingemarsson (son of Ingemar). Only

for registration purposes, for example when registering at a

university, did one need a registered family name. In the academic

world, Latin was the language of choice in those times. When Linnaeus' father went to the University of Lund,

he coined himself a Latin surname: Linnaeus. He called himself Linnaeus

after the family property Linnagård, Linnagård (Linden

farm) referring to the large linden (lime) tree the family's warden tree on the property (linn being archaic Swedish for linden). Nils Ingemarsson Linnaeus gave his son the name Carl. So the Swedish name of the boy was Carl Linnaeus. When

Carl Linnaeus enrolled in private school as student at the University

of Lund, he was registered as 'Carolus Linnaeus'. This Latinized form

was the name he used when he published his works in Latin. After he was

ennobled, in 1761, he

took the name Carl von Linné. 'Linné' is thus a shortened

version of 'Linnaeus', and 'von' is added to signify his ennoblement.

The adjectival form of his name is usually 'Linnaean'; however the

world's premier taxonomy society is named the Linnean Society of London, and publishes the journal The Linnean, awards the Linnean Medal, and so on. Linnaeus was born on the farm Råshult, located in Älmhult Municipality, in the province of Småland in

southern Sweden, on May 23, 1707. He was groomed as a youth to be a

churchman, walking in his father's path, but showed little enthusiasm

for it. There are accounts that he learned Latin as a mother tongue

along with Swedish rather than at school. In 1717 he was sent to the

primary school at the city Växjö, and in 1724 he passed to the gymnasium there, but with meager results in the clerical faculty. Instead his interest in botany made

an impression on a local physician, who realized there might be a

future in the field for the young Linnaeus, and on his recommendation

Linnaeus's father sent his son to study at the closest university, Lund University.

Linnaeus studied in Lund and tried to make something of the botanical

garden there, but because it had been neglected, it was suggested to

him that he would have better prospects at the Uppsala University; Linnaeus left for Uppsala within a year. His time in Uppsala was financially rough—too poor to buy shoes, he repaired discarded shoes and wore them -- until he became acquainted with the renowned scientist Olof Celsius, uncle of astronomer Anders Celsius who

created the temperature scale that was given his name. Celsius,

impressed with Linnaeus's knowledge and botanical collections, offered

him board and lodging. During

this period, he came upon a work which ultimately led to the

establishment of his artificial system of plant classification. This

was a review of Sébastien Vaillant's Sermo de Structura Florum (Leiden, 1718), a thin quarto in French and Latin. Through this, he became convinced of the importance of the stamens and pistils, about which he wrote a short treatise on the sexes of plants in 1729. This caught the attention of Olof Rudbeck the Younger (1660-1740), the professor of botany in the university, who subsequently appointed Linnaeus his adjunct. In 1730, Linnaeus began giving lectures in the faculty. In 1732 the Academy of Sciences at Uppsala financed Linnaeus on an expedition to Lappland in northernmost Sweden, then virtually unknown. The result of this was first The Florula Lapponica (the first work to use the Sexual System) and later the Flora Lapponica published in 1737. His journey to sub-Arctic Lapland is notable for exotic and adventurous episodes.

In

1735 Linnaeus moved to the Netherlands, where he was to spend the next

three years. Here he earned his only academic degree, at the University of Harderwijk,

in 6 days. This degree in Medicine consisted of a three day printing

job of his botanical notes in Latin. He made friends with the botanist David de Gorter. He also met the drugist Albertus Seba and the botanist Jan Frederik Gronovius and showed him a draft of his work on taxonomy, the Systema Naturae. This was published in the Netherlands the same year, as an eleven page work. Linnaeus stayed in the Netherlands for 12 months, until he made a journey to London in 1736, where he visited Oxford University and met several highly regarded people, such as the physicist Hans Sloane, the botanist Philip Miller and

the professor of botany J.J. Dillenius. The journey lasted a few

months, after which he returned to Amsterdam, and continued the

printing of his Genera Plantarum, the starting point of his taxonomy. In 1737 Linnaeus spent a year studying and working on the Heemstede garden of George Clifford, a wealthy Amsterdam banker introduced to him by Herman Boerhaave.

Clifford had many business connections with Dutch merchants and

collected plants from around the world. His garden was famous. Linnaeus

published the description of Clifford's garden as Hortus Cliffortianus. In 1738, the work was done, and he started his journey back home. On his way he stayed in Leiden for a year, during which he had his Classes Plantarum printed; then travelling to Paris, before setting sail for Stockholm. Arriving in Stockholm, he settled as a physician.

In September 1739 Linnaeus married Sara Elisabeth Morea (Moræaus)

and the marriage took place at her family farm Sveden outside Falun;

Sara he had met on one of his first scientific journeys to the county

of Dalarna already five years earlier 1734. In 1739 he was one of the

founders of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (Kungliga

vetenskapsakademin). In 1741 he ascended to the chair of medicine at

Uppsala and moved there. The position was soon exchanged for the chair

of botany. In 1743-44, Linnaeus designed today's thermometer scale by reversing that invented by Anders Celsius; originally 100 was the melting point of ice and 0 the boiling point of water. Throughout the 1740s he conducted numerous field trips to many locations in Sweden to classify plants and animals: in 1741 to Stora Alvaret on Öland and also to Gotland; in 1746 to Västergötland; and in 1749 to Scania including visits to Kullaberg.

The reports of each travel were published in Swedish to be accessible

to the general public. Apart from containing many important reports of

common life of that time, the reports have in recent years been

appreciated for their fine treatment of language, putting Linnaeus as

one of the foremost Swedish writers of the 18th century. When

not on travels, Linnaeus worked on his classifications, extending them

to the kingdom of animals and the kingdom of minerals. The last may

seem somewhat odd, but the theory of evolution was still a long time away. Linnaeus was only attempting a convenient way of categorizing the elements of the natural world. The Swedish king, Adolf Fredrik,

granted Linnaeus nobility in 1757, and after the privy council finally

had confirmed this (in 1761 after a few years of discussions) Linnaeus

took the surname von Linné, later often signing just Carl Linné. In some portraits of Linnaeus, including three with this article, he is shown bearing a sprig of Twinflower, one of his favorite plants, named in his honor in his lifetime, by Jan Frederik Gronovius (1686-1762), Dutch botanist notable as a patron of Linnaeus, as Linnaea borealis. It is the only species in its genus, and, as it is circumboreal, it can be encountered in cool northern regions of both the Old World and the New. After

his apotheosis, he continued teaching and writing. His reputation had

spread over the world, and he corresponded with many different people.

For example, Catherine II of Russia sent him seeds from her country. He also corresponded with Joannes A. Scopoli, "the Linnaeus of the Austrian Empire", who was a doctor and a botanist in Idrija, Duchy of Carniola (nowadays Slovenia). Scopoli communicated all of his research, findings, and descriptions (for example, olm and dormouse,

two little animals which were not known to Linnaeus) to him for several

years, but because of the great distance they were never able to meet.

Linnaeus named for him the solanaceous genus Scopolia from which scopolamine is derived. Of Linnaeus' seven children, five reached adult age: four girls and one boy. Only the boy, Carolus Linnaeus the Younger,

was allowed to study. He did not have the same passion as his father,

but managed to make a reputation in botany. At the father's death, the

son succeeded him as professor; however, he died only five years later.

The son is commonly referred to as filius (abbreviated "L. f.") to distinguish him from his famous father. Linnaeus' last years were troubled by weak health, and he suffered from gout and tooth aches. A stroke in

1774 greatly weakened him, and two years later he suffered another,

losing the use of his right side. He died in January 1778 in Uppsala,

during a ceremony in Uppsala Cathedral. He was buried in the cathedral. Linnaeus's

main contribution to taxonomy was to establish conventions for the

naming of living organisms that became universally accepted in the

scientific world—the work of Linnaeus represents the starting point of binomial nomenclature. In addition Linnaeus developed, during the great 18th century expansion of natural history knowledge, what became known as the Linnaean taxonomy; the system of scientific classification now widely used in the biological sciences. The Linnaean system classified nature within a hierarchy, starting with three kingdoms.

Kingdoms were divided into Classes and they, in turn, into Orders,

which were divided into Genera (singular: genus), which were divided

into Species (singular: species). Below the rank of species he

sometimes recognized taxa of a lower (unnamed) rank (for plants these

are now called "varieties"). His

groupings were based upon shared physical characteristics. Only his

groupings for animals remain to this day, and the groupings themselves

have been significantly changed since Linnaeus' conception, as have the

principles behind them. Nevertheless, Linnaeus is credited with

establishing the idea of a hierarchical structure of classification

which is based upon observable characteristics. While the underlying

details concerning what are considered to be scientifically valid

'observable characteristics' have changed with expanding knowledge (for

example, DNA sequencing, unavailable in Linnaeus' time, has proven to be a tool of considerable

utility for classifying living organisms and establishing their

relationships to each other), the fundamental principle remains sound. Linnaeus presented a concept of "race" as applied to humans, also including mythological creatures. Within Homo sapiens he proposed five taxa of a lower (unnamed) rank. These categories were Africanus, Americanus, Asiaticus, Europeanus, and Monstrosus. They were based on place of origin at first, and later on skin colour. Each race had certain characteristics that he considered endemic to individuals belonging to it. Native Americans were choleric, red, straightforward, eager and combative. Africans were phlegmatic, black, slow, relaxed and negligent. Asians were melancholic, yellow, inflexible, severe and avaricious. Europeans were sanguine and pale, muscular, swift, clever and inventive. The "monstrous" humans included such entities as the "agile and fainthearted" dwarf of the Alps, the Patagonian giant, and the monorchid Hottentot. In addition, in Amoenitates academicae (1763), he defined Homo anthropomorpha as a catch-all term for a variety of human-like mythological creatures, including the troglodyte, satyr, hydra, and phoenix.

He claimed that these creatures not only actually existed but were in

reality inaccurate descriptions of real-world ape-like creatures. He also, in Systema Naturæ, defined Homo ferus as "four-footed, mute, hairy". Included in this classification were Juvenis lupinus hessensis (wolf boys), who he thought were raised by animals, Juvenis hannoveranus (Peter of Hanover) and Puella campanica (Wild-girl of Champagne). Linnaeus' research took science on a path that diverged from what had been taught by religious authorities; rebuke followed. The Lutheran Archbishop of Uppsala accused him of impiety. The Catholic Church went further; Pope Clement XIII banned the works of Linnaeus by listing them in the Index Librorum Prohibitorum in 1758 and also condemned copies to be burned.

Returning to Sweden in 1738, he practiced medicine (specializing in the treatment of syphilis) and lectured in Stockholm before being awarded a professorship at Uppsala in

1741. At Uppsala, in the University's botanical garden, he arranged the

plants according to his system of classification; he then made three

more expeditions to various parts of Sweden and inspired a generation

of students. Linnaeus continued to revise his Systema Naturae,

which grew from a slim pamphlet into a multivolume work, as his ideas

were evolving and more and more plant and animal specimens were sent to

him from every corner of the globe. His pride in his work was very much

evident; he thought of himself as a second Adam. He liked to say 'Deus creavit, Linnaeus disposuit, ' Latin for, "God created, Linnaeus organized". This self-perception was further shown by the artwork on the cover of his Systema Naturae, which depicts a man giving Linnaean names to new creatures as they are created in the Garden of Eden.