<Back to Index>

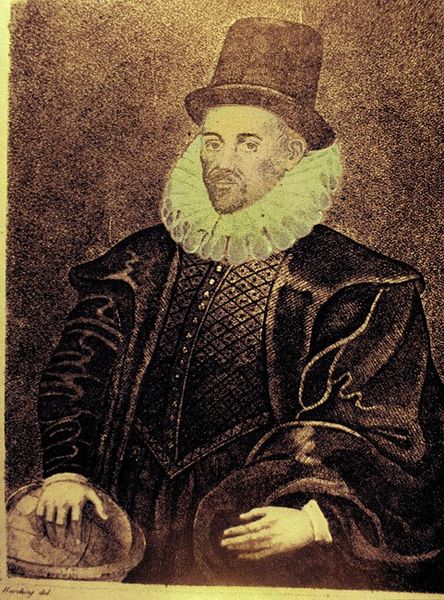

- Physician William Gilbert, 1544

- Painter Philips Wouwerman, 1619

- Queen of the United Kingdom Victoria, 1819

William Gilbert, also known as Gilbard, (Colchester, England, 24 May 1544 – London, England, 30 November 1603) was an English physician and natural philosopher. He was an early Copernican, and passionately rejected both the prevailing Aristotelian philosophy and the Scholastic method of university teaching. He is remembered today largely for his book De Magnete (1601), and is credited as one of the originators of the term electricity. He is regarded by some as the father of electrical engineering or electricity and magnetism. While today he is generally referred to as William Gilbert, he also went under the name of William Gilberd. The latter was used in his and his father's epitaph, the records of the town of Colchester, and in the Biographical Memoir in De Magnete, as well as in the name of The Gilberd School in Colchester, named after Gilbert. A unit of magnetomotive force, also known as magnetic potential, was named the gilbert in his honour.

Gilbert was educated at St John's College, Cambridge; after gaining his MD from Cambridge in 1569, and a short spell as bursar of St John's College, he left to practice medicine in London. In 1600 he was elected President of the College of Physicians (not up to that point granted a royal charter). From 1601 until his death in 1603, he was Elizabeth I's own physician, and James VI and I renewed his appointment.

His primary scientific work was De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure (On the Magnet and Magnetic Bodies, and on the Great Magnet the Earth) published in 1600. In this work, he describes many of his experiments with his model earth called the terrella. From these experiments, he concluded that the Earth was itself magnetic and that this was the reason compasses point north (previously, some believed that it was the pole star (Polaris) or a large magnetic island on the north pole that attracted the compass). He was the first to argue, correctly, that the centre of the Earth was iron, and he considered an important and related property of magnets was that they can be cut, each forming a new magnet with north and south poles.

The English word electricity was first used in 1646 by Sir Thomas Browne, derived from Gilbert's 1600 New Latin electricus, meaning "like amber". The term had been in use since the 1200s, but Gilbert was the first to use it to mean "like amber in its attractive properties". He recognized that friction with these objects removed a so-called effluvium, which would cause the attraction effect in returning to the object, though he did not realize that this substance (electric charge) was universal to all materials.

In his book, he also studied static electricity using amber; amber is called elektron in Greek, so Gilbert decided to call its effect the electric force. He invented the first electrical measuring instrument, the electroscope, in the form of a pivoted needle he called the versorium.

Like others of his day, he believed that "crystal" (quartz) was an especially hard form of water, formed from compressed ice.

Gilbert argued that electricity and magnetism were not the same thing. For evidence, he (incorrectly) pointed out that, while electrical attraction disappeared with heat, magnetic attraction did not (although it is proven that magnetism does in fact become damaged and weakened with heat). It took James Clerk Maxwell to show that both effects were aspects of a single force: electromagnetism. Even then, Maxwell simply surmised this in his A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism after much analysis. By keeping clarity, Gilbert's strong distinction advanced science for nearly 250 years.

Gilbert's magnetism was the invisible force that many other natural philosophers, such as Kepler, seized upon, incorrectly, as governing the motions that they observed. While not attributing magnetism to attraction among the stars, Gilbert pointed out the motion of the skies was due to earth's rotation, and not the rotation of the spheres, 20 years before Galileo .

Gilbert died on 30 November 1603. His cause of death is thought to have been the bubonic plague.