<Back to Index>

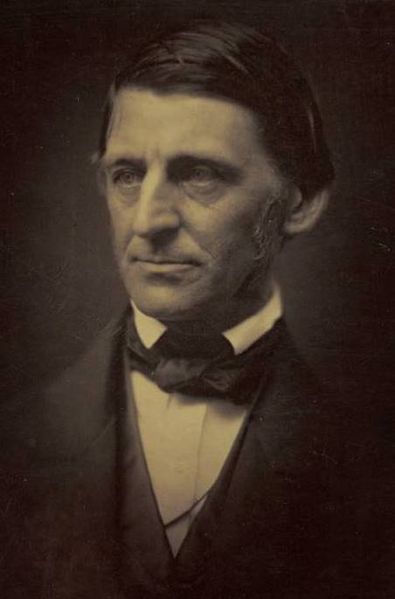

- Philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1803

- Poet Naim Frashëri, 1846

- King of Saxony Frederick Augustus III, 1865

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803 – April 27, 1882) was an American essayist, philosopher, and poet, best remembered for leading the Transcendentalist movement of the mid 19th century. His teachings directly influenced the growing New Thought movement of the mid 1800s. He was seen as a champion of individualism and a prescient critic of the countervailing pressures of society.

Emerson

gradually moved away from the religious and social beliefs of his

contemporaries, formulating and expressing the philosophy of Transcendentalism in his 1836 essay, Nature. As a result of this ground breaking work he gave a speech entitled The American Scholar in 1837, which Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. considered to be America's "Intellectual Declaration of Independence". Considered one of the great orators of the time, Emerson's enthusiasm and respect for his audience enraptured crowds. His support for abolitionism late

in life created controversy, and at times he was subject to abuse from

crowds while speaking on the topic. When asked to sum up his work, he

said his central doctrine was "the infinitude of the private man." Emerson was born in Boston, Massachusetts on May 25, 1803, son of Ruth Haskins and the Rev. William Emerson, a Unitarian minister who descended from a well-known line of ministers. He was named after his mother's brother Ralph and the father's great-grandmother Rebecca Waldo. Ralph

Waldo was the second of five sons who survived into adulthood; the

others were William, Edward, Robert Bulkeley, and Charles. Three other children — Phebe, John Clarke, and Mary Caroline — died in childhood. The

young Ralph Waldo Emerson's father died from stomach cancer on May 12,

1811, less than two weeks before Emerson's eighth birthday. Emerson was raised by his mother as well as other intellectual and spiritual

women in his family, including his aunt Mary Moody Emerson, who had a

profound impact on the young Emerson. She lived with the family off and on and maintained a constant correspondence with Emerson until her death in 1863. Emerson's formal schooling began at the Boston Latin School in 1812 when he was nine. In October 1817, at 14, Emerson went to Harvard College and

was appointed freshman messenger for the president, requiring Emerson

to fetch delinquent students and send messages to faculty. Midway

through his junior year, Emerson began keeping a list of books he had

read and started a journal in a series of notebooks that would be

called "Wide World". He

took outside jobs to cover his school expenses, including as a waiter

for the Junior Commons and as an occasional teacher working with his

uncle Samuel in Waltham, Massachusetts. By his senior year, Emerson decided to go by his middle name, Waldo. Emerson

served as Class Poet and, as was custom, presented an original poem on

Harvard's Class Day, a month before his official graduation on August

29, 1821, when he was 18. He did not stand out as a student and graduated in the exact middle of his class of 59 people. Around 1826, during a winter trip to St. Augustine, Florida, Emerson made the acquaintance of Prince Achille Murat. Murat, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte,

was only two years his senior and the two became extremely good friends

and enjoyed one another's company. The two engaged in enlightening

discussions on religion, society, philosophy, and government. After Harvard, Emerson assisted his brother William in a school for young women established in their mother's house, after he had established his own school in Chelmsford, Massachusetts; when his brother William went to Göttingen to

study divinity, Emerson took charge of the school. Over the next

several years, Emerson made his living as a schoolmaster, then went to Harvard Divinity School. Emerson's brother Edward, two years younger than he, entered the office of lawyer Daniel Webster,

after graduating Harvard first in his class. Edward's physical health

began to deteriorate and he soon suffered a mental collapse as well; he

was taken to McLean Asylum in June of 1828 at 23. Although he recovered

his mental equilibrium he died in 1834 at 29 from apparently

longstanding tuberculosis. Boston's Second Church invited Emerson to serve as its junior pastor and he was ordained on March 11, 1829. Emerson met his first wife, Ellen Louisa Tucker, in Concord, New Hampshire and married her when she was 18. The couple moved to Boston, with Emerson's mother Ruth moving with them to help take care of Ellen, who was already sick with tuberculosis. Less

than two years later, Ellen died at the age of 20 on February 8, 1831,

after uttering her last words: "I have not forgot the peace and joy". Emerson was heavily affected by her death and often visited her grave. In a journal entry dated March 29, 1831, Emerson wrote, "I visited Ellen's tomb and opened the coffin". After

his wife's death, he began to disagree with the church's methods,

writing in his journal in June 1832: "I have sometimes thought that, in

order to be a good minister, it was necessary to leave the ministry.

The profession is antiquated. In an altered age, we worship in the dead

forms of our forefathers". His disagreements with church officials over the administration of the Communion service

and misgivings about public prayer eventually led to his resignation in

1832. As he wrote, "This mode of commemorating Christ is not suitable

to me. That is reason enough why I should abandon it". Emerson toured Europe in 1832 and later wrote of his travels in English Traits (1857). He left aboard the brig Jasper on Christmas Day, sailing first to Malta. During his European trip, he met William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Stuart Mill, and Thomas Carlyle.

Carlyle in particular was a strong influence on Emerson; Emerson would

later serve as an unofficial literary agent in the United States for

Carlyle. The two would maintain correspondence until Carlyle's death in

1881. Emerson returned to the United States on October 9, 1833, and lived with his mother in Newton, Massachusetts until November 1834, when he moved to Concord, Massachusetts to live with his step-grandfather Dr. Ezra Ripley at what was later named The Old Manse. In 1835, he bought a house on the Cambridge and Concord Turnpike in Concord, Massachusetts, now open to the public as the Ralph Waldo Emerson House, and quickly became one of the leading citizens in the town. He married his second wife Lydia Jackson in her home town of Plymouth, Massachusetts, on September 14, 1835. He called her Lidian and she called him Mr. Emerson. Their children were Waldo, Ellen, Edith, and Edward Waldo Emerson. Ellen was named for his first wife, at Lidian's suggestion. Another of Emerson's bright and promising younger brothers, Charles, born in 1808, died in 1836, also of consumption, making him the third young person in Emerson's innermost circle to die in a period of a few years. Emerson lived a financially conservative lifestyle. He had inherited some wealth after his wife's death, though he brought a lawsuit against the Tucker family in 1836 to get it. He received $11,674.79 in July 1837. Emerson and other like-minded intellectuals founded the Transcendental Club, which served as a center for the movement. Its first official meeting was held on September 19, 1836. Emerson anonymously published his first essay, Nature, in September 1836. A year later, on August 31, 1837, Emerson delivered his now-famous Phi Beta Kappa address, "The American Scholar", then

known as "An Oration, Delivered before the Phi Beta Kappa Society at

Cambridge"; it was renamed for a collection of essays in 1849. In

the speech, Emerson declared literary independence in the United States

and urged Americans to create a writing style all their own and free

from Europe. James Russell Lowell, who was a student at Harvard at the time, called it "an event without former parallel on our literary annals". Another member of the audience, Reverend John Pierce, called it "an apparently incoherent and unintelligible address". In 1837, Emerson befriended Henry David Thoreau.

Though they had likely met as early as 1835, in the fall of 1837,

Emerson asked Thoreau, "Do you keep a journal?" The question went on to

have a lifelong inspiration for Thoreau. On July 15, 1838, Emerson was invited to Divinity Hall, Harvard Divinity School for the school's graduation address, which came to be known as his "Divinity School Address". Emerson discounted Biblical miracles and proclaimed that, while Jesus was a great man, he was not God: historical Christianity, he said, had turned Jesus into a "demigod, as the Orientals or the Greeks would describe Osiris or Apollo". His comments outraged the establishment and the general Protestant community. For this, he was denounced as an atheist, and

a poisoner of young men's minds. Despite the roar of critics, he made

no reply, leaving others to put forward a defense. He was not invited

back to speak at Harvard for another thirty years. The Transcendental group began to publish its flagship journal, The Dial, in July 1840. They planned the journal as early as October 1839, but work did not begin until the first week of 1840. George Ripley was its managing editor and Margaret Fuller was its first editor, having been hand-chosen by Emerson after several others had declined the role. Fuller stayed on for about two years and Emerson took over, utilizing the journal to promote talented young writers including William Ellery Channing and Thoreau. In January 1842, Emerson's first son Waldo died from scarlet fever. Emerson wrote of his grief in the poem "Threnody" ("For this losing is true dying"), and the essay "Experience". In the same year, William James was born, and Emerson agreed to be his godfather. It was in 1842 that Emerson published Essays, his second book, which included the famous essay, "Self-Reliance."

His aunt called it a "strange medley of atheism and false

independence," but it gained favorable reviews in London and Paris.

This book, and its popular reception, more than any of Emerson's

contributions to date laid the groundwork for his international fame. Bronson Alcott announced

his plans in November 1842 to find "a farm of a hundred acres in

excellent condition with good buildings, a good orchard and grounds". Charles Lane purchased a 90-acre (360,000 m2) farm in Harvard, Massachusetts, in May 1843 for what would become Fruitlands, a community based on Utopian ideals inspired in part by Transcendentalism. The

farm would run based on a communal effort, using no animals for labor,

and its participants would eat no meat and use no wool or leather.

Emerson said he felt "sad at heart" for not engaging in the experiment

himself. Even

so, he did not feel Fruitlands would be a success. "Their whole

doctrine is spiritual", he wrote, "but they always end with saying,

Give us much land and money". Even

Alcott admitted he was not prepared for the difficulty in operating

Fruitlands. "None of us were prepared to actualize practically the

ideal life of which we dreamed. So we fell apart", he wrote. After its failure, Emerson helped buy a farm for Alcott's family in Concord which Alcott named "Hillside". The Dial ceased publication in April 1844; Horace Greeley reported it as an end to the "most original and thoughtful periodical ever published in this country". Emerson made a living as a popular lecturer in New England and much of the rest of the country. From 1847 to 1848, he toured England, Scotland, and Ireland. He

also visited Paris between the February Revolution and the bloody June

Days. When he arrived, he saw the stumps where trees had been cut down

to form barricades in the February riots. On May 21 he stood on the

Champ de Mars in the midst of mass celebrations for concord, peace and

labor. He wrote in his journal: "At the end of the year we shall take

account, & see if the Revolution was worth the trees." He had begun lecturing in 1833; by the 1850s he was giving as many as 80 per year. Emerson spoke on a wide variety of subjects and many of his essays grew out of

his lectures. He charged between $10 and $50 for each appearance,

bringing him about $800 to $1,000 per year. His earnings allowed him to expand his property, buying eleven acres of land by Walden Pond and a few more acres in a neighboring pine grove. He wrote that he was "landlord and waterlord of 14 acres, more or less". In 1845, Emerson's journals show he was reading the Bhagavad Gita and Henry Thomas Colebrooke's Essays on the Vedas. Emerson was strongly influenced by the Vedas, and much of his writing has strong shades of nondualism. Emerson was introduced to Indian philosophy when reading the works of French philosopher Victor Cousin. In February 1852, Emerson and James Freeman Clarke and William Henry Channing edited an edition of the works and letters of Margaret Fuller, who had died in 1850. Within a week of her death, her New York editor Horace Greeley suggested to Emerson that a biography of Fuller, to be called Margaret and Her Friends, be prepared quickly "before the interest excited by her sad decease has passed away". Published with the title The Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli, Fuller's words were heavily censored or rewritten. The

three editors were not concerned about accuracy; they believed public

interest in Fuller was temporary and that she would not survive as a

historical figure. Even

so, for a time, it was the best-selling biography of the decade and

went through thirteen editions before the end of the century. Walt Whitman published the innovative poetry collection Leaves of Grass in

1855 and sent a copy to Emerson for his opinion. Emerson responded

positively, sending a flattering five-page letter as a response. Emerson's approval helped the first edition of Leaves of Grass stir up significant interest and convinced Whitman to issue a second edition shortly thereafter. This edition quoted a phrase from Emerson's letter, printed in gold leaf on the cover: "I Greet You at the Beginning of a Great Career". Emerson took offense that this letter was made public and later became more critical of the work. Though Emerson was anti-slavery, he did not immediately become active in the abolitionist movement. He voted for Abraham Lincoln in

1860, but Emerson was disappointed that Lincoln was more concerned

about preserving the Union than eliminating slavery outright. Once the American Civil War broke out, Emerson made it clear that he believed in immediate emancipation of the slaves. Emerson gave a public lecture in Washington, D.C. on

January 31, 1862, and declared: "The South calls slavery an

institution... I call it destitution... Emancipation is the demand of

civilization". The next day, February 1, his friend Charles Sumner took him to meet Lincoln at the White House; his misgivings about Lincoln began to soften after this meeting. On May 6, 1862, Emerson's protege Henry David Thoreau died of tuberculosis at the age of 44 and Emerson delivered his eulogy. Emerson would continuously refer to Thoreau as his best friend, despite a falling out that began in 1849 after Thoreau published A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. Another friend, Nathaniel Hawthorne,

died two years after Thoreau in 1864. Emerson served as one of the

pallbearers as Hawthorne was buried in Concord, as Emerson wrote, "in a

pomp of sunshine and verdure". Beginning as early as the summer of 1871 or in the spring of 1872, Emerson was losing his memory and suffered from aphasia. By

the end of the decade, he forgot his own name at times and, when anyone

asked how he felt, he responded, "Quite well; I have lost my mental

faculties, but am perfectly well". Emerson's

Concord home caught fire on July 24, 1872; Emerson called for help from

neighbors and, giving up on putting out the flames, all attempted to

save as many objects as possible. The fire was put out by Ephraim Bull, Jr., the one-armed son of Ephraim Wales Bull. Donations were collected by friends to help the Emersons rebuild, including $5,000 gathered by Francis Cabot Lowell, another $10,000 collected by Le Baron Russell Briggs, and a personal donation of $1,000 from George Bancroft. Support

for shelter was offered as well; though the Emersons ended up staying

with family at the Old Manse, invitations came from Anne Lynch Botta, James Elliot Cabot, James Thomas Fields and Annie Adams Fields. The

fire marked an end to Emerson's serious lecturing career; from then on,

he would lecture only on special occasions and only in front of

familiar audiences. While

the house was being rebuilt, Emerson took a trip to England, the main

European continent, and Egypt. He left on October 23, 1872, along with

his daughter Ellen while his wife Lidian spent time at the Old Manse and with friends. Emerson and his daughter Ellen returned to the United States on the ship Olympus along with friend Charles Eliot Norton on April 15, 1873. Emerson's return to Concord was celebrated by the town and school was canceled that day. In late 1874, Emerson published an anthology of poetry called Parnassus, which included poems by Anna Laetitia Barbauld, Julia Caroline Dorr, Jean Ingelow, Lucy Larcom, Jones Very, as well as Thoreau and several others. The anthology was originally prepared as early as the fall of 1871 but was delayed when the publishers asked for revisions. The

problems with his memory had become embarrassing to Emerson and he

ceased his public appearances by 1879. As Holmes wrote, "Emerson is

afraid to trust himself in society much, on account of the failure of

his memory and the great difficulty he finds in getting the words he

wants. It is painful to witness his embarrassment at times". On

April 19, 1882, Emerson went walking despite having an apparent cold

and was caught in a sudden rain shower. Two days later, he was

diagnosed with pneumonia. He died on April 27, 1882. Emerson is buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, Massachusetts. He was placed in his coffin wearing a white robe given by American sculptor Daniel Chester French. There is evidence suggesting that Emerson may have been bisexual. During

his early years at Harvard, he found himself "strangely attracted" to a

young freshman named Martin Gay about whom he wrote sexually charged

poetry. Gay would be only the first of his infatuations and interests, with Nathaniel Hawthorne numbered among them.