<Back to Index>

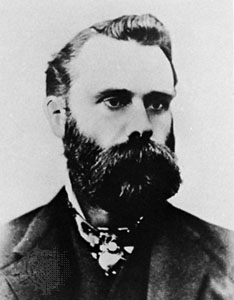

- Journalist Charles Henry Dow, 1851

- Musical Instrument Designer Antoine-Joseph "Adolphe" Sax, 1814

- Sultan of the Ottoman Empire Suleiman I (the Magnificent), 1494

PAGE SPONSOR

Charles Henry Dow (November 6, 1851 – December 4, 1902) was an American journalist who co-founded Dow Jones & Company with Edward Jones and Charles Bergstresser.

Dow also founded The Wall Street Journal, which has become one of the most respected financial publications in the world. He also invented the Dow Jones Industrial Average as

part of his research into market movements. He developed a series of

principles for understanding and analyzing market behavior which later

became known as Dow theory, the groundwork for technical analysis. Charles Henry Dow was born in Sterling, Connecticut on November 6, 1851. When he was six years old, his father, who was a farmer, died. The family lived in the hills of eastern Connecticut, not far from Rhode Island. Dow did not have much education or training, but he managed to find work at the age of 21 with the Springfield Daily Republican, in Massachusetts. He worked there from 1872 until 1875 as a city reporter for Samuel Bowles, who taught his reporters to write crisp, detailed articles. Dow then moved on to Rhode Island, joining the Providence Star, where he worked for two years as a night editor. He also reported for the Providence Evening Press. In 1877, Dow joined the staff of the prominent Providence Journal.

Charles Danielson, the editor there, had not wanted to hire the

26-year-old, but Dow would not take no for an answer. Upon learning

that Dow had worked for Bowles for three years, Danielson reconsidered

and gave Dow a job writing business stories. Dow

specialized in articles on regional history, some of which were later

published in pamphlet form. Dow made history come alive in his writing

by explaining the development of various industries and their future

prospects. In 1877, he published a History of Steam Navigation between

New York and Providence. Three years later, he published Newport: The City by the Sea. It was an account of Newport, Rhode Island's

settlement, rise, decline, and rebirth as a summer vacation spot and

the location of a naval academy, training station, and war college. Dow

reported on Newport real estate investments, recording the money earned

and lost during the city's history. He also wrote histories of public

education and the prison system in the state. Danielson was so

impressed with Dow's careful research that he assigned him to accompany

a group of bankers and reporters to Leadville, Colorado, to report on silver mining. The bankers wanted the publicity in order to gain investors in the mines. In 1879, Dow and various tycoons, geologists, lawmakers,

and investors set out on a four-day train trip to reach Colorado. Dow

learned a great deal about the world of money on that journey as the

men smoked cigars, played cards, and swapped stories. He interviewed

many highly successful financiers and heard what sort of information

the investors on Wall Street needed to make money. The businessmen

seemed to like and trust Dow, knowing that he would quote them

accurately and keep a confidence. Dow wrote nine "Leadville Letters"

based on his experiences there. He described the Rocky Mountains, the mining companies, and the boomtown's gambling, saloons, and dance halls. He also wrote of raw capitalism and

the information that drove investments, turning people into

millionaires in a moment. He described the disappearance of the

individual mine-owners and the financiers who underwrote shares in

large mining consortiums. In his last letter, Dow warned, "Mining

securities are not the thing for widows and orphans or country

clergymen, or unworldly people of any kind to own. But for a

businessman, who must take risks in order to make money; who will buy

nothing without careful, thorough investigation; and who will not risk

more than he is able to lose, there is no other investment in the

market today as tempting as mining stock." In 1880, Dow left Providence for New York City,

realizing that the ideal location for business and financial reporting

was there. The 29-year-old found work at the Kiernan Wall Street

Financial News Bureau, which delivered by messenger hand written

financial news to banks and brokerages. When John Kiernan asked Dow to

find another reporter for the Bureau, Dow invited Edward Davis Jones to

work with him. Jones and Dow had met when they worked together at the

Providence Evening Press. Jones, a Brown University dropout,

could skillfully and quickly analyze a financial report. He, like Dow,

was committed to reporting on Wall Street without bias. Other reporters

could be bribed into reporting favorably on a company to drive up stock

prices. Dow and Jones refused to manipulate the stock market. The two young men believed that Wall Street needed another financial news bureau. In November 1882,

they started their own agency, Dow, Jones & Company. The business'

headquarters was located in the basement of a candy store. Dow, Jones,

and their four employees could not handle all the work, so they brought

in Charles Bergstresser, who became a partner. Bergstresser's strength

lay in his interviewing skills. Jones once remarked that he could make

a wooden Indian talk. In November 1883,

the company started putting out an afternoon two-page summary of the

day's financial news called the Customers' Afternoon Letter. It soon

achieved a circulation of over 1,000 subscribers and was considered an

important news source for investors. It included the Dow Jones stock average, an index that included nine railroad issues, one steamship line, and Western Union. In

1889, the company had 50 employees. The partners realized that the time

was right to transform their two-page news summary into a real

newspaper. The first issue of The Wall Street Journal appeared on July 8, 1889.

It cost two cents per issue or five dollars for a one-year

subscription. Dow was the editor and Jones managed the deskwork. The

paper gave its readers a policy statement: "Its object is to give fully

and fairly the daily news attending the fluctuations in prices of stocks, bonds, and some classes of commodities.

It will aim steadily at being a paper of news and not a paper of

opinions." The paper's motto was "The truth in its proper use." Its

editors promised to put out a paper that could not be controlled by

advertisers. The paper had a private wire to Boston and telegraph connections to Washington, Philadelphia, and Chicago. It also had correspondents in several cities, including London. Dow

often warned his reporters about exchanging slanted stories for stock

tips or free stock. Crusading for honesty in financial reporting, Dow

would publish the names of companies that hesitated to give information

about profit and loss. Soon after that, the newspaper gained power and respect from the reading public. Vermont Royster, a later editor of the Wall Street Journal said that Dow always believed that business information was not the "private province of brokers and tycoons". In 1898, the Wall Street Journal put

out its first morning edition. The paper now covered more than just

financial news. It also covered war, which it reported without

rhetoric, unlike many of the other papers. Dow also added an editorial

column called "Review and Outlook," and "Answers to Inquirers," in

which readers sent investment questions to be answered. Edward Jones

retired in 1899,

but Dow and Bergstresser continued working. Dow still wrote editorials,

now focusing on the place that government held in American business. The Wall Street Journal started a precedent in reporting during the election of 1900 by endorsing a political candidate, the incumbent president William McKinley. In the 1890s, Dow saw that the recession was ending. In 1893, many mergers began taking place, resulting in the formation of huge corporations. These corporations sought

markets for their stock shares. The wildly speculative market meant

investors needed information about stock activity. Dow took this

opportunity to devise the Dow Jones industrial average in

1896. By tracking the closing stock prices of twelve companies, adding

up their stock prices, and dividing by twelve, Dow came up with his

average. The first such average appeared in the Wall Street Journal on May 26, 1896. The industrial index became a popular indicator of stock market activity. In 1897, the company created an average for railroad stocks. Dow also developed the Dow theory,

which stated that a relationship existed between stock market trends

and other business activity. Dow felt that if the industrial average

and the railroad average both moved in the same direction, it meant

that a meaningful economic shift was occurring. He also concluded that

if both indexes reached a new high, it signaled a bull market was underway. Dow did not believe that his ideas should be used as the only

forecaster of market ups and downs. He thought they should be only one

tool of many that investors used to make business decisions.

In 1902, Dow began to have health problems and Bergstresser wanted to retire. The two sold their shares of the company to Clarence Barron,

their Boston correspondent. Dow wrote his last editorial in April 1902.

About eight months later, on December 4, 1902, he died in Brooklyn, New York, at the age of 52.