<Back to Index>

- Physicist and Chemist Marie Skłodowska Curie, 1867

- Novelist Albert Camus, 1913

- People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs Lev Davidovich Trotsky, 1879

PAGE SPONSOR

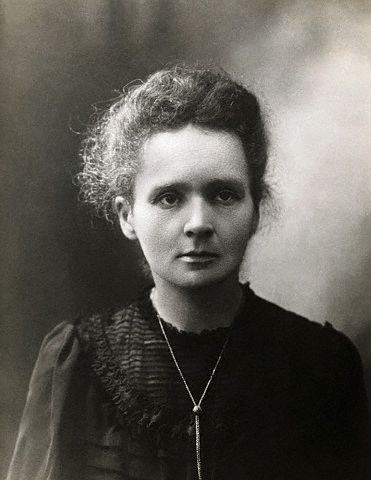

Marie Skłodowska Curie (7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934) was a physicist and chemist of Polish upbringing and subsequent French citizenship. She was a pioneer in the field of radioactivity and the first person honored with two Nobel Prizes — in physics and chemistry. She was also the first woman professor at the University of Paris.

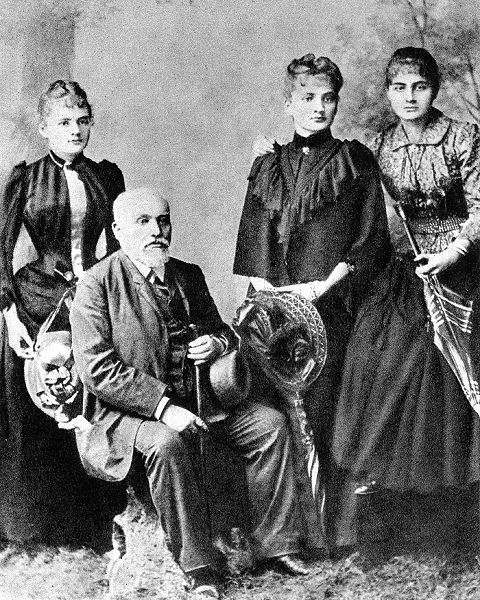

She was born Maria Skłodowska in Warsaw (then in Vistula Land, Russian Empire; now in Poland) and lived there until she was twenty-four. In 1891 she followed her older sister Bronisława to study in Paris, where she obtained her higher degrees and conducted her subsequent scientific work. She founded the Curie Institutes in Paris and Warsaw. Her husband Pierre Curie shared her Nobel prize in physics. Her daughter Irène Joliot-Curie and son-in-law, Frédéric Joliot-Curie, also shared a Nobel prize. Her achievements include the creation of a theory of radioactivity (a term she coined), techniques for isolating radioactive isotopes, and the discovery of two new elements, polonium and radium. Under her direction, the world's first studies were conducted into the treatment of neoplasms (cancers) using radioactive isotopes. While an actively loyal French citizen, she never lost her sense of Polish identity. She named the first new chemical element that she discovered polonium (1898) for her native country, and in 1932 she founded a Radium Institute (now the Maria Skłodowska–Curie Institute of Oncology) in her home town, Warsaw, headed by her physician sister Bronisława. Maria

Skłodowska was born in Warsaw, Poland, on 7 November 1867, the fifth

and youngest child of well-known teachers Bronisława and Władysław

Skłodowski. Maria's older siblings were Zofia (born 1862), Józef

(1863), Bronisława (1865), and Helena (1866). Maria's grandfather Józef Skłodowski had been a respected teacher in Lublin, where he had taught the young Bolesław Prus. Her

father Władysław Skłodowski taught mathematics and physics, subjects

that Maria was to pursue, and he successively, was director of two

Warsaw gymnasia for boys, in addition to lodging boys in the family home. Her mother, Bronisława, operated a prestigious Warsaw boarding school for girls. She suffered from tuberculosis and died when Maria was twelve. Maria's father was an atheist and her mother a devout Catholic. Two years earlier, Maria's oldest sibling, Zofia, had died of typhus. The deaths of her mother and sister, according to Robert William Reid, caused Maria to give up Catholicism and become agnostic. When

she was ten years old, Maria began attending the boarding school that

her mother had operated while she was well; next Maria attended a gymnasium for

girls, from which she graduated on 12 June 1883. She spent the

following year in the countryside with her father's relatives, and the

next with her father in Warsaw, where she did some tutoring. On

both the paternal and maternal sides, the family had lost their

property and fortunes through patriotic involvements in Polish national

uprisings. This condemned each subsequent generation, including that of

Maria, her elder sisters, and brother to a difficult struggle to get

ahead in life.

Maria

made an agreement with her sister, Bronisława, that she would give her

financial assistance during Bronisława's medical studies in Paris, in

exchange for similar assistance two years later. In connection with this, she took a position as governess. First with a lawyer's family in Kraków, then for two years in Ciechanów with

a landed family, the Żorawskis, who were relatives of her father. While

working for the latter family, she fell in love with their son, Kazimierz Żorawski,

which was reciprocated by this future eminent mathematician. His

parents, however, rejected the idea of his marrying the penniless

relative and Kazimierz was unable to oppose them. Maria lost her

position as governess. She found another with the Fuchs family in Sopot, on the Baltic Sea coast, where she spent the next year, all the while financially assisting her sister. At

the beginning of 1890, Bronisława, a few months after she married

Kazimierz Dłuski, invited Maria to join them in Paris. Maria declined because she could not afford the university tuition and was still counting on marrying Kazimierz Żorawski. She returned home to her father in Warsaw, where she remained till the fall of 1891. She tutored, studied at the clandestine Floating University, and began her practical scientific training in a laboratory at the Museum of Industry and Agriculture at Krakowskie Przedmieście 66, near Warsaw's Old Town. The laboratory was run by her cousin Józef Boguski, who had been assistant in St. Petersburg to the great Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleyev. In

October 1891, at her sister's insistence and after receiving a letter

from Żorawski, in which he definitively broke his relationship with

her, she decided to go to France after all. Maria's

loss of the relationship with Żorawski was tragic for both. He soon

earned a doctorate and pursued an academic career as a mathematician,

becoming a professor and rector of Kraków University and president of the Warsaw Society of Learning. Still, as an old man and a mathematics professor at the Warsaw Polytechnic,

he would sit contemplatively before the statue of Maria Skłodowska

which had been erected before the Radium Institute that she had founded. In Paris, Maria briefly found shelter with her sister and brother-in-law before renting a primitive garret and proceeding with her studies of physics, chemistry, and mathematics at the Sorbonne (the University of Paris). Skłodowska

studied during the day and tutored evenings, barely earning her keep.

In 1893 she was awarded a degree in physics and began work in an

industrial laboratory at Lippman's. Meanwhile she continued studying at

the Sorbonne, and in 1894, earned a degree in mathematics. In the same year Pierre Curie entered her life. He was an instructor in the School of Physics and Chemistry, the École Supérieure de Physique et de Chimie Industrielles de la Ville de Paris (ESPCI).

Skłodowska had begun her scientific career in Paris with an

investigation of the magnetic properties of various steels; it was

their mutual interest in magnetism that drew Skłodowska and Curie together. Her

departure for the summer to Warsaw only enhanced their mutual feelings

for each other. She still was laboring under the illusion that she

would be able to return to Poland and work in her chosen field of

study. When she was denied a place at Kraków University merely because she was a woman, however,

she returned to Paris. Almost a year later, in July 1895, she and

Pierre Curie married, and thereafter the two physicists hardly ever

left their laboratory. They shared two hobbies, long bicycle trips and

journeys abroad, which brought them even closer. Maria had found a new

love, a partner, and scientific collaborator upon whom she could depend. In 1896 Henri Becquerel discovered that uranium salts emitted rays that resembled X-rays in their penetrating power. He demonstrated that this radiation, unlike phosphorescence,

did not depend on an external source of energy, but seemed to arise

spontaneously from uranium itself. Becquerel had, in fact, discovered

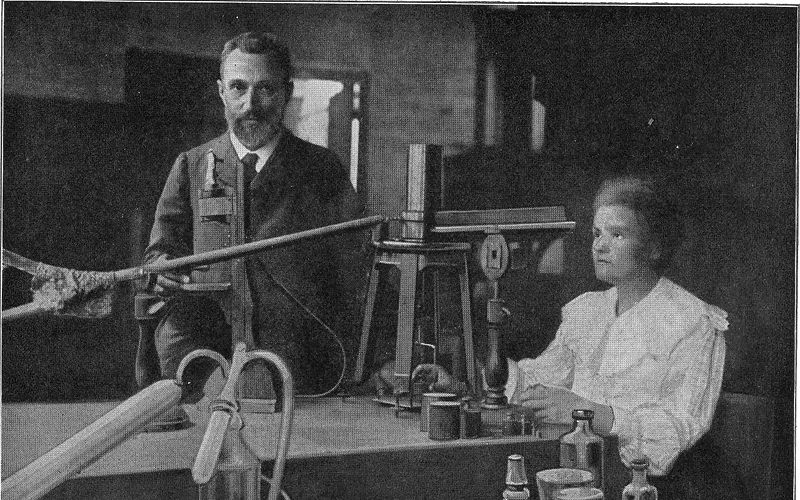

radioactivity. Skłodowska–Curie decided to look into uranium rays as a possible field of research for a thesis. She used a clever technique to investigate samples. Fifteen years earlier, her husband and his brother had invented the electrometer,

a sensitive device for measuring electrical charge. Using the Curie

electrometer, she discovered that uranium rays caused the air around a

sample to conduct electricity. Using

this technique, her first result was the finding that the activity of

the uranium compounds depended only on the quantity of uranium present.

She had shown that the radiation was not the outcome of some interaction of molecules, but must come from the atom itself. In scientific terms, this was the most important single piece of work that she conducted. Skłodowska–Curie's systematic studies had included two uranium minerals, pitchblende and torbernite (also

known as chalcolite). Her electrometer showed that pitchblende was four

times as active as uranium itself, and chalcolite twice as active. She

concluded that, if her earlier results relating the quantity of uranium

to its activity were correct, then these two minerals must contain

small quantities of some other substance that was far more active than

uranium itself. In

her systematic search for other substances beside uranium salts that

emitted radiation, Skłodowska–Curie had found that the element thorium likewise, was radioactive. She was acutely aware of the importance of promptly publishing her discoveries and thus establishing her priority. Had not Becquerel, two years earlier, presented his discovery to the Académie des Sciences the day after he made it, credit for the discovery of radioactivity, and even a Nobel Prize, would have gone to Silvanus Thompson instead.

Skłodowska–Curie chose the same rapid means of publication. Her paper,

giving a brief and simple account of her work, was presented for her to

the Académie on 12 April 1898 by her former professor, Gabriel Lippmann. Even

so, just as Thompson had been beaten by Becquerel, so Skłodowska–Curie

was beaten in the race to tell of her discovery that thorium gives off

rays in the same way as uranium. Two months earlier, Gerhard Schmidt

had published his own finding in Berlin. At

that time, however, no one else in the world of physics had noticed

what Skłodowska–Curie recorded in a sentence of her paper, describing

how much greater were the activities of pitchblende and chalcolite

compared to uranium itself: "The fact is very remarkable, and leads to

the belief that these minerals may contain an element which is much

more active than uranium." She later would recall how she felt "a

passionate desire to verify this hypothesis as rapidly as possible." Pierre

Curie was sure that what she had discovered was not a spurious effect.

He was so intrigued that he decided to drop his work on crystals

temporarily and to join her. On 14 April 1898 they optimistically

weighed out a 100-gram sample of pitchblende and ground it with a

pestle and mortar. They did not realize at the time that what they were

searching for was present in such minute quantities that they

eventually would have to process tonnes of the ore. Since they were unaware of the deleterious effects of radiation exposure attendant on their chronic unprotected work with radioactive substances,

Skłodowska–Curie and her husband had no idea what price they would pay

for the effect of their research upon their health.

In

July 1898, Skłodowska–Curie and her husband published a paper together,

announcing the existence of an element which they named "polonium",

in honor of her native Poland, which would for another twenty years

remain partitioned among three empires. On 26 December 1898 the Curies

announced the existence of a second element, which they named "radium" for its intense radioactivity — a word that they coined. Pitchblende

is a complex mineral. The chemical separation of its constituents was

an arduous task. The discovery of polonium had been relatively easy;

chemically it resembles the element bismuth,

and polonium was the only bismuth-like substance in the ore. Radium,

however, was more elusive. It is closely related, chemically, to barium, and pitchblende contains both elements.

By 1898 the Curies had obtained traces of radium, but appreciable

quantities, uncontaminated with barium, still were beyond reach. The Curies undertook the arduous task of separating out radium salt by differential crystallization. From a ton of pitchblende, one-tenth of a gram of radium chloride was

separated in 1902. By 1910 Skłodowska–Curie, working on without her

husband, who had been killed accidentally in 1906, had isolated the

pure radium metal. In an unusual decision, Marie Skłodowska–Curie intentionally refrained from patenting the radium-isolation process, so that the scientific community could do research unhindered. In 1903, under the supervision of Henri Becquerel, Marie was awarded her DSc from the University of Paris. In 1903, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded Pierre Curie, Marie Curie and Henri Becquerel the Nobel Prize in Physics, "in recognition of the extraordinary services they have rendered by their joint researches on the radiation phenomena discovered by Professor Henri Becquerel." Skłodowska–Curie and her husband were unable to go to Stockholm to receive the prize in person, but they shared its financial proceeds with needy acquaintances, including students. On

receiving the Nobel Prize, Marie and Pierre Curie suddenly became very

famous. The Sorbonne gave Pierre a professorship and permitted him to

establish his own laboratory, in which Skłodowska–Curie became the

director of research. In 1897 and 1904, respectively, Skłodowska–Curie gave birth to their daughters, Irène and Eve Curie. She later hired Polish governesses to teach her native language to them, and send or take them on visits to Poland. Skłodowska–Curie was the first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize. Eight years later, she would receive the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, "in recognition of her services to the advancement of chemistry by the

discovery of the elements radium and polonium, by the isolation of

radium and the study of the nature and compounds of this remarkable

element." A month after accepting her 1911 Nobel Prize, she was hospitalized with depression and a kidney ailment. Skłodowska–Curie

was the first person to win or share two Nobel Prizes. She is one of

only two people who have been awarded a Nobel Prize in two different

fields, the other being Linus Pauling (for Chemistry and for Peace). Nevertheless, in 1911 the French Academy of Sciences refused to abandon its prejudice against women, and she failed by two votes to be elected as a member. Instead, Édouard Branly, an inventor who had helped Guglielmo Marconi develop the wireless telegraph, was elected. It would be her doctoral student, Marguerite Perey, who would become the first woman elected to the Academy — in 1962, over half a century later. On 19 April 1906 Pierre was killed in a street accident. Walking across the Rue Dauphine in

heavy rain, he was struck by a horse-drawn vehicle and fell under its

wheels, his skull was fractured. While it has been speculated that

previously, he may have been weakened by prolonged radiation exposure,

it has not been proven that this was the cause of the accident. Skłodowska–Curie

was devastated by the death of her husband. She noted that, as of that

moment she suddenly had become "an incurably and wretchedly lonely

person". On 13 May 1906 the Sorbonne physics department decided to

retain the chair that had been created for Pierre Curie and they

entrusted it to Skłodowska–Curie together with full authority over the

laboratory. This allowed her to emerge from Pierre's shadow. She became

the first woman to become a professor at the Sorbonne, and in her

exhausting work regime, sought a meaning for her life. Recognition for her work grew to new heights, and in 1911 the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded

her a second Nobel Prize, this time for Chemistry. A delegation of

celebrated Polish men of learning, headed by world-famous novelist, Henryk Sienkiewicz, encouraged her to return to Poland and continue her research in her native country. In 1911, it was revealed that during 1910–11 Skłodowska–Curie had conducted an affair of about a year's duration with physicist Paul Langevin, a former student of Pierre Curie. He

was a married man who was estranged from his wife. This resulted in a

press scandal that was exploited by her academic opponents. Despite her

fame as a scientist working for France, the public's attitude tended

toward xenophobia — the same that had led to the Dreyfus Affair - which

also fueled false speculation that Skłodowska–Curie was Jewish. She was

five years older than Langevin and was portrayed in the tabloids as a

home-wrecker. Later, Skłodowska–Curie's granddaughter, Hélène Joliot, married Langevin's grandson, Michel Langevin. Skłodowska–Curie's

second Nobel Prize, in 1911, enabled her to talk the French government

into funding the building of a private Radium Institute (Institut du radium, now the Institut Curie),

which was built in 1914 and at which research was conducted in

chemistry, physics, and medicine. The Institute became a crucible of

Nobel Prize winners, producing four more, including her daughter Irène Joliot-Curie and her son-in-law, Frédéric Joliot-Curie.

During World War I, Skłodowska-Curie pushed for the use of mobile radiography units, which came to be popularly known as petites Curies ("Little Curies"), for the treatment of wounded soldiers. These units were powered using tubes of radium emanation, a colorless, radioactive gas given off by radium, later identified as radon.

Skłodowska-Curie provided the tubes of radium, derived from the

material she purified. Also, promptly after the war started, she

donated the gold Nobel Prize medals she and her husband had been awarded, to the war effort. In

1921, Skłodowska-Curie was welcomed triumphantly when she toured the

United States to raise funds for research on radium. These distractions

from her scientific labors and the attendant publicity, caused her much

discomfort, but provided resources needed for her work. Her second

American tour in 1929 succeeded in equipping the Warsaw Radium Institute, founded in 1925 with her sister, Bronisława, as director. In her later years, Skłodowska-Curie headed the Pasteur Institute and a radioactivity laboratory created for her by the University of Paris.

Skłodowska–Curie visited Poland a last time in the spring of 1934. Only a couple of months later, Skłodowska-Curie died. Her death on 4 July 1934 at the Sancellemoz Sanatorium in Passy, in Haute-Savoie, eastern France, was from aplastic anemia, almost certainly contracted from exposure to radiation. The damaging effects of ionizing radiation were

not then known, and much of her work had been carried out in a shed,

without taking any safety measures. She had carried test tubes

containing radioactive isotopes in her pocket and stored them in her

desk drawer, remarking on the pretty blue-green light that the

substances gave off in the dark. She was interred at the cemetery in Sceaux,

alongside her husband Pierre. Sixty years later, in 1995, in honor of

their achievements, the remains of both were transferred to the Paris Panthéon. She became the first - and so far only - woman to be honored in this way. Her laboratory is preserved at the Musée Curie. Due

to their levels of radioactivity, her papers from the 1890s are

considered too dangerous to handle. Even her cookbook is highly

radioactive. They are kept in lead-lined boxes, and those who wish to

consult them must wear protective clothing. The physical and societal aspects

of the work of the Curies contributed substantially to shaping the

world of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Cornell University

professor L. Pearce Williams observes: If

the work of Maria Skłodowska–Curie helped overturn established ideas in

physics and chemistry, it has had an equally profound effect in the

societal sphere. In order to attain her scientific achievements, she

had to overcome barriers that were placed in her way because she was a

woman, in both her native and her adoptive country. This aspect of her

life and career is highlighted in Françoise Giroud's Marie Curie: A Life, which emphasizes Skłodowska's role as a feminist precursor. She was ahead of her time, emancipated, independent, and in addition uncorrupted. Albert Einstein is reported to have remarked that she was probably the only person who was not corrupted by the fame that she had won.