<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Norbert Wiener, 1894

- Playwright Eugène Ionesco, 1909

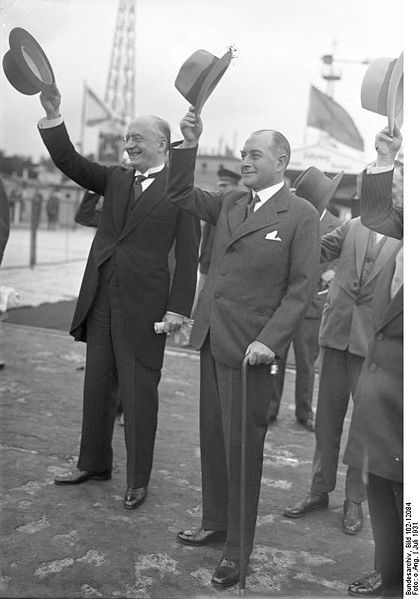

- Chancellor of Germany Heinrich Brüning, 1885

PAGE SPONSOR

Heinrich Brüning (26 November 1885 – 30 March 1970) was a German politician during the Weimar Republic. He served as Chancellor of Germany from 1930 to 1932, making him the longest serving Chancellor of the Weimar Republic.

Born in Münster in Westphalia, Brüning lost his father when he was one year old and thus his elder brother Hermann Joseph played a major part in his upbringing. Although raised a devout Catholic, Brüning was also influenced by Lutheranism's concept of duty, since the Münster region was home to both Catholics, who formed a majority (especially in the western part) and some Prussian-influenced Protestants.

After finishing his schooling, he first tended towards the legal profession, but then studied Philosophy, History, German and Political Science at Strasbourg, the London School of Economics and Bonn, where he achieved his doctorate in national economy. One of his professors at Strasbourg, who had a major influence on Brüning was the historian Friedrich Meinecke.

A volunteer in World War I, he served from 1915 - 1918 as a machine gunner, receiving rank as an officer and earning an Iron Cross. He did not approve of the 1918 German revolution, which saw the establishment of the Weimar government, and in its aftermath he decided not to pursue his academic career further, but preferred helping those who had fallen into trouble. He collaborated with the social reformer Carl Sonnenschein and worked in the "Secretariat for social student work", helping demobilised soldiers to study and work. After six months he entered the Prussian welfare department and became a close associate of the minister Adam Stegerwald. Stegerwald, also leader of the Christian trade unions, made him chief executive of the unions in 1920, a post Brüning retained until 1930. In 1923 he was actively involved in organizing the passive resistance in the "Ruhrkampf". As the editor of the union newspaper Der Deutsche (The German), he advocated a "social popular state" and "Christian democracy," based on the ideas of Catholic Corporatism.

He also joined the Centre Party and in 1924 he was elected to the Reichstag, representing Breslau. In parliament, Brüning quickly made a name for himself as a financial expert and managed to push though the "lex Brüning", which restricted the wage tax. He always insisted on a disciplined, thrifty approach towards money, criticizing both an increase of civil service salaries and the luxury of profiteers. Recognized for his expertise, this personal reserve and calmness hampered dealing with him on personal level. From 1928 to 1930, he was a member of the Prussian parliament and, in 1929, he was elected chairman of the Centre Party's faction in the Reichstag.

In 1930, when the grand coalition under the Social Democrat Hermann Müller collapsed, Brüning was appointed chancellor on 29 March 1930. The government was confronted with the economic crisis caused by the Great Depression.

Brüning disclosed to his associates in the German Labour

Federation that his chief aim as chancellor would be to liberate the

German economy from the burden of continuing to pay war reparations.

This would require an unpopular policy of tight credit and a rollback

of all wage and salary increases. Brüning's financial and economic

acumen combined with his openness to social questions made him a

candidate for chancellor and his service as a front officer made him

acceptable to President Paul von Hindenburg. The Reichstag rejected

his measures within a month. President Hindenburg, already bent on

reducing the influence of the Reichstag, saw this event as the "failure

of parliament" and, with Brüning's consent called for new

elections. These elections cost the parties of the grand coalition

their majority and brought gains to both Communists and National Socialists.

This left Brüning without any hope of reforging a party coalition

and forced him to base his administration on the presidential emergency decree ("Notverordnung") of Article 48 of

the Constitution, circumventing parliament, and the informal toleration

of this practice by the parties. Brüning coined the term

"authoritative (or authoritarian) democracy" to describe this form of

government based on the cooperation of the president and parliament. Hindenburg desired to base the government on the parties of the right but the right-wing German National People's Party (DNVP) refused to support Brüning's government. To the president's dismay, Brüning therefore had to rely on his own Centre Party, the only party that fully supported him, and the toleration of the Social Democrats. Brüning's

measures were implemented in the summer by presidential decree and made

him extremely unpopular among the lower and middle classes. As

unemployment continued to rise, his cuts in welfare and reductions of

wages combined with rising prices and taxes, increased misery among

workers and the jobless. This gave rise to the quote: "Brüning

verordnet Not!" (Brüning decrees need), alluding to his measures

being implemented by "Notverordnung". These

effects undermined the support of the Social Democrats for the

government and the liberal and conservative cabinet members favoured

opening the government to the right. President Hindenburg, pushed by his camarilla and military chief Kurt von Schleicher, also advocated such a move and insisted on a cabinet reshuffle and especially the resignation of ministers Wirth and Guérard, both from the Centre Party. The

president's wishes also hampered the government's resolution in

combating the extremist parties and their respective paramilitary

organisations. While the chancellor and president agreed that the Nazis'

brutality, intolerance and demagogy rendered them unfit for government,

Brüning believed the government was strong enough to steer Germany

through the crisis without the support of the Nazis. Nonetheless, he

negotiated with Hitler about

toleration or a formal coalition, without yielding to the Nazis any

position of power or the full support by presidential decree. Because

of these reservations, the negotiations came to nothing and as street

violence rose to new heights in April 1932, Brüning had both the

communist "Rotfrontkämpferbund" and the Nazi Sturmabteilung banned.

The unfavourable reactions of the right-wing circles to that move

further undermined Hindenburg's support for Brüning. Even

before then, Brüning had agonized over how to stem the growing

Nazi tide, especially since Hindenburg could not be expected to survive

another full term as president should he choose to run again. If

Hindenburg were to die in office, Hitler would be a strong favorite to

succeed him. By the end of 1931, Brüning thought he had hit upon a

solution — restoring the Hohenzollern monarchy. He would persuade the Reichstag and Reichsrat to

cancel the 1932 presidential election and simply extend Hindenburg's

term by a two-thirds vote in both chambers. He would then have

parliament proclaim a monarchy, with Hindenburg as regent. On

Hindenburg's death, one of Crown Prince William's sons would be invited to assume the throne. However, unlike the old German Empire,

the restored monarchy would have been a British-style constitutional

monarchy. All of the major parties except the Communists were at least

willing to give Brüning's plan some support, seeing this as the

last real chance of stopping Hitler. However, the plan foundered when

Hindenburg, an old-line monarchist at heart, refused to stand down in

favour of anyone except William II himself.

Brüning tried to impress upon him that neither the Social

Democrats nor the international community would tolerate any return of

William II, and that the Crown Prince wouldn't be acceptable either.

This only angered Hindenburg further, and he threw Brüning out of

his office.

In

the international theatre, Brüning tried to alleviate the burden

of reparation payments and to achieve German equality in the rearmament question. In 1930, he replied to Aristide Briand's initiative to form a "United States of Europe" by demanding full equality for Germany. In 1931 plans for a customs union between Germany and Austria were shattered by French opposition. In the same year, the Hoover memorandum

postponed reparation payments and in summer 1932, after Brüning's

resignation, his successors could reap the fruits of his policy at the Lausanne conference, which reduced German reparations to a final installment of 3 billion marks. Negotiations over rearmament failed at the 1932 Geneva Conference shortly before his resignation, but in December the "Five powers agreement" accepted Germany's military equality. Hindenburg

was initially not willing to run for reelection, but was prevailed upon

to change his mind. In 1932, Brüning, along with virtually the

entire German left and centre, vigorously campaigned for Hindenburg's

reelection, calling him a "venerate historical personality" and "the

keeper of the constitution". Hindenburg was re-elected against Hitler,

but he considered it shameful to be elected by the votes of "Reds" and

"Catholes", as he called Social Democrats and the Centre Party, and

compensated for this "shame" by moving further to the right. At the

same time, his failing health only increased the influence of the

camarilla. At that time, Brüning was viciously attacked by the Prussian Junkers, led by Elard von Oldenburg-Januschau. They opposed his policies of distributing land to unemployed workers and denounced him as an "Agro-bolshevik" to Hindenburg. The president asked Brüning to make way by stepping down as chancellor while remaining foreign minister.

Brüning refused to serve as a figure-head for such a right-wing

government and announced his cabinet's resignation on 30 May 1932,

"hundred metres before the finish", as he called it. He sternly

rejected all suggestions to make the president's disloyal behaviour

public, both because he considered such a move indecent and because he

still considered Hindenburg the "last bulwark" of the German people. After his resignation, Brüning was invited by Ludwig Kaas to take over the leadership of the Centre Party,

but the former chancellor declined and asked Kaas to stay. Brüning

supported his party's determined opposition to his successor, Franz von Papen, and also of re-establishing a working parliament by cooperation with the National Socialists, negotiating with Gregor Strasser. After Adolf Hitler became

chancellor on 30 January 1933, Brüning vigorously campaigned

against the new government in the March elections. Later that month, he

was a main advocate for rejecting the Hitler administrations's Enabling Act,

calling it the "most monstrous resolution ever demanded of a

parliament." He nonetheless yielded to party discipline and voted in

favour of the bill. Only the Social Democrats voted

against the law. When Kaas was held up in Rome and resigned from his

post as chairman of the Centre Party, Brüning was elected chairman

on 6 May. However, Brüning yielded to increasing persecution by

the National Socialist controlled government by dissolving the Centre

Party on 6 July. To escape Hitler's political purges, Brüning fled Germany in 1934 via the Netherlands and settled in the United Kingdom. In 1939, he became professor for political science at Harvard University.

He warned the American public about Hitler's plans for war and later

about Soviet expansion, but in both cases his advice went unheeded. In 1947, he returned to Germany and taught at the University of Cologne. He was a critic of Adenauer's policy of Western integration and as he saw no prospect of resuming his political career, he returned to the United States. In 1968, he published the tome "Speeches and essays". Brüning died in 1970 in Norwich, Vermont, and was buried in his home town Münster. Posthumously, his "Memoirs 1918 - 1934" were published, a source not undisputed among historians. Brüning

remains a controversial figure, since it is debated whether he was the

"last bulwark of the Republic" or the "Republic's undertaker". His

intentions certainly were to protect the Republican government, but his

policies also contributed to the gradual demise of the Weimar Republic from

1930 to 1933. Comparing some current leaders to Brüning remains a

sure way to create a highly emotional response in German political

discussions.