<Back to Index>

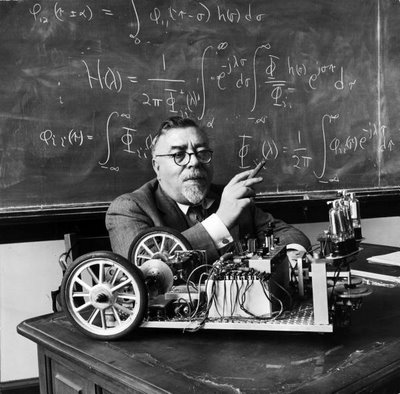

- Mathematician Norbert Wiener, 1894

- Playwright Eugène Ionesco, 1909

- Chancellor of Germany Heinrich Brüning, 1885

PAGE SPONSOR

Norbert Wiener (November 26, 1894, Columbia, Missouri – March 18, 1964, Stockholm, Sweden) was an American pure and applied mathematician.

A famous child prodigy, Wiener went on to become a pioneer in the study of stochastic and noise processes, contributing work relevant to electronic engineering, electronic communication, and control systems. Wiener is the founder of cybernetics, a field that formalizes the notion of feedback, with many implications for engineering, systems control, computer science, biology, philosophy, and the organization of society. Wiener was the first child of Leo Wiener and Bertha Kahn, both Ashkenazi Jews of Polish and German descent,

respectively. Employing teaching methods of his own invention, Leo

educated Norbert at home until 1903, except for a brief interlude when

Norbert was 7 years of age. Wiener became a child prodigy in part due to his father's tutelage. Earning his living teaching German and Slavic languages,

Leo read widely and accumulated a personal library from which the young

Norbert benefited greatly. Leo also had ample ability in mathematics,

and tutored his son in the subject until he left home. After graduating from Ayer High School in 1906 at 11 years of age, Wiener entered Tufts College. He was awarded a BA in mathematics in 1909 at the age of 14, whereupon he began graduate studies in zoology at Harvard. In 1910 he transferred to Cornell to study philosophy. The

next year he returned to Harvard, while still continuing his

philosophical studies. Back at Harvard, Wiener came under the influence

of Edward Vermilye Huntington, whose mathematical interests ranged from axiomatic foundations to problems posed by engineering. Harvard awarded Wiener a Ph.D. in 1912, when he was a mere 18, for a dissertation on mathematical logic, supervised by Karl Schmidt. In that dissertation, he was the first to see that the ordered pair can be defined in terms of elementary set theory. Hence relations can be wholly grounded in set theory, so that the theory of relations does not require any axioms or primitive notions distinct from those of set theory. In 1921, Kazimierz Kuratowski proposed a simplification of Wiener's definition of the ordered pair, and that simplification has been in common use ever since. In 1914, Wiener traveled to Europe, to study under Bertrand Russell and G.H. Hardy at Cambridge University, and under David Hilbert and Edmund Landau at the University of Göttingen. In 1915-16, he taught philosophy at Harvard, then worked for General Electric and wrote for the Encyclopedia Americana. When World War I broke out, Oswald Veblen invited him to work on ballistics at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in

Maryland. Thus Wiener, an eventual pacifist, wore a uniform 1917-18.

Living and working with other mathematicians strengthened and deepened

his interest in mathematics. After the war, Wiener was unable to secure a position at Harvard and was rejected for a position at the University of Melbourne. At W. F. Osgood's invitation, Wiener became an instructor in mathematics at MIT, where he spent the remainder of his career, rising to Professor. In 1926, Wiener returned to Europe as a Guggenheim scholar. He spent most of his time at Göttingen and with Hardy at Cambridge, working on Brownian motion, the Fourier integral, Dirichlet's problem, harmonic analysis, and the Tauberian theorems. In

1926, Wiener's parents arranged his marriage to a German immigrant,

Margaret Engemann, who was not Jewish; they had two daughters. During World War II, his work on the automatic aiming and firing of anti-aircraft guns led Wiener to communication theory and eventually to formulate cybernetics. After the war, his prominence helped MIT to recruit a research team in cognitive science, made up of researchers in neuropsychology and the mathematics and biophysics of the nervous system, including Warren Sturgis McCulloch and Walter Pitts. These men went on to make pioneering contributions to computer science and artificial intelligence.

Shortly after the group was formed, Wiener broke off all contact with

its members. Speculation still flourishes as to why this split occurred. Wiener went on to break new ground in cybernetics, robotics, computer control, and automation. He shared his theories and findings with other researchers, and credited the contributions of others. These included Soviet researchers and their findings. Wiener's connections with them placed him under suspicion during the Cold War.

He was a strong advocate of automation to improve the standard of

living, and to overcome economic underdevelopment. His ideas became

influential in India, whose government he advised during the 1950s. Wiener declined an invitation to join the Manhattan Project.

After the war, he became increasingly concerned with what he saw as

political interference in scientific research, and the militarization

of science. His article "A Scientist Rebels" in the January 1947 issue

of The Atlantic Monthly urged

scientists to consider the ethical implications of their work. After

the war, he refused to accept any government funding or to work on

military projects. The way Wiener's stance towards nuclear weapons and

the Cold War contrasted with that of John von Neumann is the central theme of ``John Von Neumann and Norbert Wiener " Heims (1980). Wiener was as a pioneer in the study of stochastic and noise processes, contributing work relevant to electronic engineering, electronic communication, and control systems. Wiener also founded cybernetics, a field that formalizes the notion of feedback and has implications for engineering, systems control, computer science, biology, philosophy, and the organization of society. He was influenced by William Ross Ashby. Wiener's work in cybernetics influenced Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, and through them, many fields of Anthropology, Sociology, and Education.

A simple mathematical representation of Brownian motion, the Wiener equation, named after Wiener, assumes the current velocity of a fluid particle fluctuates. In signal processing, the Wiener filter is a filter proposed by Wiener during the 1940s and published in 1949. Its purpose is to reduce the amount of noise present in a signal by comparison with an estimation of the desired noiseless signal. The Wiener process is a continuous-time stochastic process named in honor of Wiener. It is often called Brownian motion', after Robert Brown. It is one of the best known Lévy processes, càdlàg stochastic

processes with stationary statistical independence increments, and

occurs frequently in pure and applied mathematics, economics and

physics. Wiener's tauberian theorem is a 1932 result of Wiener. It put the capstone on the field of tauberian theorems in summability theory, on the face of it a chapter of real analysis, by showing that most of the known results could be encapsulated in a principle from harmonic analysis. As now formulated, the theorem of Wiener has no obvious connection to tauberian theorems, which deal with infinite series; the translation from results formulated for integrals, or using the language of functional analysis and Banach algebras, is however a relatively routine process once the idea is grasped. The Paley–Wiener theorem relates growth properties of entire functions on Cn and Fourier transformation of Schwartz distributions of compact support. The Wiener–Khinchin theorem, also known as the Wiener – Khintchine theorem and sometimes as the Khinchin – Kolmogorov theorem,

states that the power spectral density of a wide-sense-stationary

random process is the Fourier transform of the corresponding

autocorrelation function. An abstract Wiener space is a mathematical object in measure theory,

used to construct a "decent", strictly positive and locally finite

measure on an infinite-dimensional vector space. Wiener's original

construction only applied to the space of real-valued continuous paths

on the unit interval, known as classical Wiener space. Leonard Gross provided the generalization to the case of a general separable Banach space. The notion of a Banach space itself was independently discovered by both Wiener and Stefan Banach at around the same time.