<Back to Index>

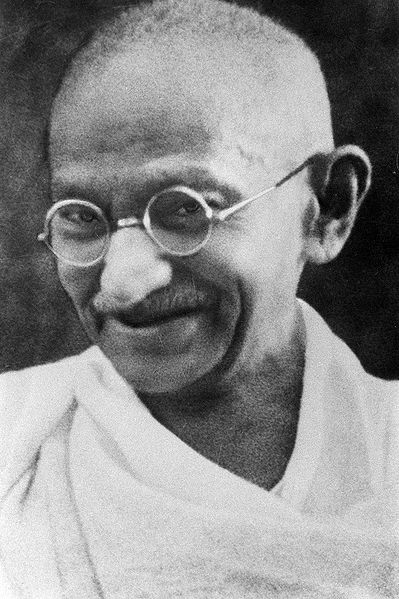

- Philosopher and Politician Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, 1869

- Painter Hans Thoma, 1839

- 2nd President of Germany Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg, 1847

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (Hindi: मोहनदास करमचंद गाँधी, Gujarati: મોહનદાસ કરમચંદ ગાંધી,; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948) was the pre-eminent political and spiritual leader of India during the Indian independence movement. He was the pioneer of satyagraha — resistance to tyranny through mass civil disobedience, a philosophy firmly founded upon ahimsa or total nonviolence — which led India to independence and inspired movements for civil rights and freedom across the world. Gandhi is commonly known around the world as Mahatma Gandhi (Sanskrit: महात्मा mahātmā or "Great Soul", an honorific first applied to him by Rabindranath Tagore), and in India also as Bapu (Gujarati: બાપુ, bāpu or "Father"). He is officially honoured in India as the Father of the Nation; his birthday, 2 October, is commemorated there as Gandhi Jayanti, a national holiday, and worldwide as the International Day of Non-Violence.

Gandhi first employed non-violent civil disobedience while

an expatriate lawyer in South Africa, during the resident Indian

community's struggle for civil rights. After his return to India in

1915, he organized protests by peasants, farmers, and urban labourers

concerning excessive land-tax and discrimination. After assuming

leadership of the Indian National Congress in 1921, Gandhi led nationwide campaigns to ease poverty, expand women's rights, build religious and ethnic amity, end untouchability, and increase economic self-reliance. Above all, he aimed to achieve Swaraj or the independence of India from foreign domination. Gandhi famously led his followers in the Non-cooperation movement that protested the British-imposed salt tax with the 400 km (240 mi) Dandi Salt March in 1930. Later, in 1942, he launched the Quit India civil disobedience movement

demanding immediate independence for India. Gandhi spent a number of

years in jail in both South Africa and India. As a practitioner of ahimsa, he swore to speak the truth and advocated that others do the same. Gandhi lived modestly in a self-sufficient residential community and wore the traditional Indian dhoti and shawl, woven with yarn he had hand spun himself. He ate simple vegetarian food, eventually adopting a fruitarian diet, and also undertook long fasts as a means of both self-purification and social protest. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on 2 October 1869 in Porbandar, a coastal town in present-day Gujarat, India. His father, Karamchand Gandhi (1822–1885), who belonged to the Hindu Modh community, was the diwan (Prime Minister) of Porbander state, a small princely state in the Kathiawar Agency of British India. His grandfather's name was Uttamchand Gandhi, fondly called Utta Gandhi. His mother, Putlibai, who came from the Hindu Pranami Vaishnava community, was Karamchand's fourth wife, the first three wives having apparently died in childbirth. Growing up with a devout mother and the Jain traditions

of the region, the young Mohandas absorbed early the influences that

would play an important role in his adult life; these included

compassion for sentient beings, vegetarianism, fasting for

self-purification, and mutual tolerance between individuals of

different creeds. The Indian classics, especially the stories of Shravana and Maharaja Harishchandra from

the Indian epics, had a great impact on Gandhi in his childhood. The

story of Harishchandra, a well known tale of an ancient Indian king and

a truthful hero, haunted Gandhi as a boy. Gandhi in his autobiography

admits that it left an indelible impression on his mind. He writes: "It

haunted me and I must have acted Harishchandra to myself times without

number." Gandhi's early self-identification with Truth and Love as

supreme values is traceable to his identification with these epic

characters. In May 1883, the 13-year old Mohandas was married to 14-year old Kasturbai Makhanji (her first name was usually shortened to "Kasturba," and affectionately to "Ba") in an arranged child marriage, as was the custom in the region. Recalling

about the day of their marriage he once said that " As we didn't know

much about marriage, for us it meant only wearing new clothes, eating

sweets and playing with relatives." However, as was also the custom of

the region, the adolescent bride was to spend much time at her parents' house, and away from her husband. In

1885, when Gandhi was 15, the couple's first child was born, but

survived only a few days; Gandhi's father, Karamchand Gandhi, had died

earlier that year. Mohandas and Kasturba had four more children, all sons: Harilal, born in 1888; Manilal, born in 1892; Ramdas, born in 1897; and Devdas,

born in 1900. At his middle school in Porbandar and high school in

Rajkot, Gandhi remained an average student academically. He passed the matriculation exam for Samaldas College at Bhavnagar, Gujarat with some difficulty. While there, he was unhappy, in part because his family wanted him to become a barrister. On 4 September 1888, less than a month shy of his 19th birthday, Gandhi traveled to London, England, to study law at University College London and to train as a barrister.

His time in London, the Imperial capital, was influenced by a vow he

had made to his mother in the presence of the Jain monk Becharji, upon

leaving India, to observe the Hindu precepts of abstinence from meat,

alcohol, and promiscuity. Although

Gandhi experimented with adopting "English" customs — taking dancing

lessons for example — he could not stomach the bland vegetarian food

offered by his landlady and he was always hungry until he found one of

London's few vegetarian restaurants. Influenced by Salt's book, he joined the Vegetarian Society, was elected to its executive committee, and started a local Bayswater chapter. Some of the vegetarians he met were members of the Theosophical Society, which had been founded in 1875 to further universal brotherhood, and which was devoted to the study of Buddhist and Hindu literature. They encouraged Gandhi to join them in reading the Bhagavad Gita both in translation as well as in the original. Not having shown a particular interest in religion before, he became interested in religious thought and began to read both Hindu as well as Christian scriptures. Gandhi was called to the bar on June 10, 1891 and left London for India on June 12, 1891, where he learned that his mother had died while he was in London, his family having kept the news from him. His attempts at establishing a law practice in Mumbai failed and, later, after applying and being turned down for a part-time job as a high school teacher, he ended up returning to Rajkot to

make a modest living drafting petitions for litigants, a business he

was forced to close when he ran afoul of a British officer. In his

autobiography, he refers to this incident as an unsuccessful attempt to

lobby on behalf of his older brother. It

was in this climate that, in April 1893, he accepted a year-long

contract from Dada Abdulla & Co., an Indian firm, to a post in the Colony of Natal, South Africa, then part of the British Empire. In South Africa, Gandhi faced discrimination directed at Indians. He was thrown off a train at Pietermaritzburg after refusing to move from the first class to a third class coach while holding a valid first class ticket. Traveling

farther on by stagecoach he was beaten by a driver for refusing to

travel on the foot board to make room for a European passenger. He

suffered other hardships on the journey as well, including being barred

from several hotels. In another incident, the magistrate of a Durban court ordered Gandhi to remove his turban - which he refused to do. These

events were a turning point in his life, awakening him to social

injustice and influencing his subsequent social activism. It was

through witnessing first hand the racism, prejudice and injustice against Indians in South Africa that Gandhi started to question his people's status within the British Empire, and his own place in society. Gandhi

extended his original period of stay in South Africa to assist Indians

in opposing a bill to deny them the right to vote. Though unable to

halt the bill's passage, his campaign was successful in drawing

attention to the grievances of Indians in South Africa. He helped found

the Natal Indian Congress in 1894, and

through this organization, he molded the Indian community of South

Africa into a homogeneous political force. In January 1897, when Gandhi

landed in Durban he was attacked by a mob of white settlers and escaped

only through the efforts of the wife of the police superintendent. He,

however, refused to press charges against any member of the mob,

stating it was one of his principles not to seek redress for a personal

wrong in a court of law. In 1906, the Transvaal government

promulgated a new Act compelling registration of the colony's Indian

population. At a mass protest meeting held in Johannesburg on 11

September that year, Gandhi adopted his still evolving methodology of satyagraha (devotion to the truth), or non-violent protest, for the first time, calling on

his fellow Indians to defy the new law and suffer the punishments for

doing so, rather than resist through violent means. This plan was

adopted, leading to a seven-year struggle in which thousands of Indians

were jailed (including Gandhi), flogged, or even shot, for striking,

refusing to register, burning their registration cards or engaging in

other forms of non-violent resistance. While the government was

successful in repressing the Indian protesters, the public outcry

stemming from the harsh methods employed by the South African

government in the face of peaceful Indian protesters finally forced

South African General Jan Christiaan Smuts to negotiate a compromise with Gandhi. Gandhi's ideas took shape and the concept of satyagraha matured during this struggle. Some of Gandhi's early South African articles are controversial. On 7 March 1908, Gandhi wrote in the Indian Opinion of his time in a South African prison: "Kaffirs are as a rule uncivilized - the convicts even more so. They are troublesome, very dirty and live almost like animals." Writing

on the subject of immigration in 1903, Gandhi commented: "We believe as

much in the purity of race as we think they do... We believe also that

the white race in South Africa should be the predominating race." During

his time in South Africa, Gandhi protested repeatedly about the social

classification of blacks with Indians, who he described as "undoubtedly

infinitely superior to the Kaffirs". Remarks such as these have led some to accuse Gandhi of racism. Two

professors of history who specialize in South Africa, Surendra Bhana

and Goolam Vahed, examined this controversy in their text, The Making of a Political Reformer: Gandhi in South Africa, 1893–1914. (New

Delhi: Manohar, 2005). They focus in Chapter 1, "Gandhi, Africans and

Indians in Colonial Natal" on the relationship between the African and

Indian communities under "White rule" and policies which enforced

segregation (and, they argue, inevitable conflict between these

communities). Of this relationship they state that, "the young Gandhi

was influenced by segregationist notions prevalent in the 1890s." At

the same time, they state, "Gandhi's experiences in jail seemed to make

him more sensitive to their plight...the later Gandhi mellowed; he

seemed much less categorical in his expression of prejudice against

Africans, and much more open to seeing points of common cause. His

negative views in the Johannesburg jail were reserved for hardened

African prisoners rather than Africans generally." Former President of South Africa Nelson Mandela is a follower of Gandhi, despite efforts in 2003 on the part of Gandhi's critics to prevent the unveiling of a statue of Gandhi in Johannesburg. Bhana and Vahed commented on the events surrounding the unveiling in the conclusion to The Making of a Political Reformer: Gandhi in South Africa, 1893–1914.

In the section "Gandhi's Legacy to South Africa," they note that

"Gandhi inspired succeeding generations of South African activists

seeking to end White rule. This legacy connects him to Nelson Mandela...in a sense Mandela completed what Gandhi started." In 1906, after the British introduced a new poll-tax, Zulus in

South Africa killed two British officers. In response, the British

declared a war against the Zulus. Gandhi actively encouraged the

British to recruit Indians. He argued that Indians should support the

war efforts in order to legitimize their claims to full citizenship.

The British, however, refused to commission Indians as army officers.

Nonetheless, they accepted Gandhi's offer to let a detachment of

Indians volunteer as a stretcher bearer corps to treat wounded British

soldiers. This corps was commanded by Gandhi. On 21 July 1906, Gandhi

wrote in Indian Opinion:

"The corps had been formed at the instance of the Natal Government by

way of experiment, in connection with the operations against the

Natives consists of twenty three Indians". Gandhi urged the Indian population in South Africa to join the war through his columns in Indian Opinion:

“If the Government only realized what reserve force is being wasted,

they would make use of it and give Indians the opportunity of a

thorough training for actual warfare.” In

Gandhi's opinion, the Draft Ordinance of 1906 brought the status of

Indians below the level of Natives. He therefore urged Indians to

resist the Ordinance along the lines of satyagraha by taking the example of "Kaffirs".

In his words, "Even the half-castes and kaffirs, who are less advanced

than we, have resisted the government. The pass law applies to them as

well, but they do not take out passes." In 1927 Gandhi wrote of the event: "The Boer War had

not brought home to me the horrors of war with anything like the

vividness that the [Zulu] 'rebellion' did. This was no war but a

man-hunt, not only in my opinion, but also in that of many Englishmen with whom I had occasion to talk."

In April 1918, during the latter part of World War I, Gandhi was invited by the Viceroy to a War Conference in Delhi. Perhaps to show his support for the Empire and help his case for India's independence, Gandhi agreed to actively recruit Indians for the war effort. In contrast to the Zulu War of 1906 and

the outbreak of World War I in 1914, when he recruited volunteers for

the Ambulance Corps, this time Gandhi attempted to recruit combatants.

In a June 1918 leaflet entitled "Appeal for Enlistment", Gandhi wrote

"To bring about such a state of things we should have the ability to

defend ourselves, that is, the ability to bear arms and to use

them... If we want to learn the use of arms with the greatest possible

despatch, it is our duty to enlist ourselves in the army." He did however stipulate in a letter to the Viceroy's private secretary that he "personally will not kill or injure anybody, friend or foe." Gandhi's war recruitment campaign brought into question his consistency on nonviolence as his friend Charlie Andrews confirms,

"Personally I have never been able to reconcile this with his own

conduct in other respects, and it is one of the points where I have

found myself in painful disagreement." Gandhi's private secretary also

acknowledges that "The question of the consistency between his creed of

'Ahimsa' (non-violence) and his recruiting campaign was raised not only

then but has been discussed ever since." Gandhi's first major achievements came in 1918 with the Champaran agitation and Kheda Satyagraha, although in the latter it was indigo and

other cash crops instead of the food crops necessary for their

survival. Suppressed by the militias of the landlords (mostly British),

they were given measly compensation, leaving them mired in extreme

poverty. The villages were kept extremely dirty and unhygienic; and

alcoholism, untouchability and purdah were

rampant. Now in the throes of a devastating famine, the British levied

a tax which they insisted on increasing. The situation was desperate. In Kheda in Gujarat, the problem was the same. Gandhi established an ashram there,

organizing scores of his veteran supporters and fresh volunteers from

the region. He organized a detailed study and survey of the villages,

accounting for the atrocities and terrible episodes of suffering,

including the general state of degenerate living. Building on the

confidence of villagers, he began leading the clean-up of villages,

building of schools and hospitals and encouraging the village

leadership to undo and condemn many social evils, as accounted above. But

his main impact came when he was arrested by police on the charge of

creating unrest and was ordered to leave the province. Hundreds of

thousands of people protested and rallied outside the jail, police

stations and courts demanding his release, which the court reluctantly

granted. Gandhi led organized protests and strikes against the

landlords who, with the guidance of the British government, signed an

agreement granting the poor farmers of the region more compensation and

control over farming, and cancellation of revenue hikes and its

collection until the famine ended. It was during this agitation, that

Gandhi was addressed by the people as Bapu (Father) and Mahatma (Great Soul). In Kheda, Sardar Patel represented

the farmers in negotiations with the British, who suspended revenue

collection and released all the prisoners. As a result, Gandhi's fame

spread all over the nation. He is also now called as "Father of the

nation" in Indian.

Gandhi employed non-cooperation, non-violence and peaceful resistance as his "weapons" in the struggle against the British. In Punjab, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of civilians by British troops (also known as the Amritsar Massacre)

caused deep trauma to the nation, leading to increased public anger and

acts of violence. Gandhi criticized both the actions of the British Raj and

the retaliatory violence of Indians. He authored the resolution

offering condolences to British civilian victims and condemning the

riots which, after initial opposition in the party, was accepted

following Gandhi's emotional speech advocating his principle that all

violence was evil and could not be justified. But

it was after the massacre and subsequent violence that Gandhi's mind

focused upon obtaining complete self-government and control of all

Indian government institutions, maturing soon into Swaraj or complete individual, spiritual, political independence. In December 1921, Gandhi was invested with executive authority on behalf of the Indian National Congress. Under his leadership, the Congress was reorganized with a new constitution, with the goal of Swaraj.

Membership in the party was opened to anyone prepared to pay a token

fee. A hierarchy of committees was set up to improve discipline,

transforming the party from an elite organization to one of mass

national appeal. Gandhi expanded his non-violence platform to include

the swadeshi policy — the boycott of foreign-made goods, especially British goods. Linked to this was his advocacy that khadi (homespun

cloth) be worn by all Indians instead of British-made textiles. Gandhi

exhorted Indian men and women, rich or poor, to spend time each day

spinning khadi in support of the independence movement. This

was a strategy to inculcate discipline and dedication to weed out the

unwilling and ambitious, and to include women in the movement at a time

when many thought that such activities were not respectable activities

for women. In addition to boycotting British products, Gandhi urged the

people to boycott British educational institutions and law courts, to

resign from government employment, and to forsake British titles and honours. "Non-cooperation"

enjoyed widespread appeal and success, increasing excitement and

participation from all strata of Indian society. Yet, just as the

movement reached its apex, it ended abruptly as a result of a violent

clash in the town of Chauri Chaura, Uttar Pradesh,

in February 1922. Fearing that the movement was about to take a turn

towards violence, and convinced that this would be the undoing of all

his work, Gandhi called off the campaign of mass civil disobedience. Gandhi

was arrested on 10 March 1922, tried for sedition, and sentenced to six

years' imprisonment. He began his sentence on 18 March 1922. He was

released in February 1924 for an appendicitis operation, having served only 2 years. Without

Gandhi's uniting personality, the Indian National Congress began to

splinter during his years in prison, splitting into two factions, one

led by Chitta Ranjan Das and Motilal Nehru favouring party participation in the legislatures, and the other led by Chakravarti Rajagopalachari and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel,

opposing this move. Furthermore, cooperation among Hindus and Muslims,

which had been strong at the height of the non-violence campaign, was

breaking down. Gandhi attempted to bridge these differences through

many means, including a three-week fast in the autumn of 1924, but with

limited success. Gandhi

stayed out of active politics and, as such, the limelight for most of

the 1920s. He focused instead on resolving the wedge between the Swaraj

Party and the Indian National Congress, and expanding initiatives

against untouchability, alcoholism, ignorance and poverty. He returned

to the fore in 1928. In the preceding year, the British government had

appointed a new constitutional reform commission under Sir John Simon,

which did not include any Indian as its member. The result was a

boycott of the commission by Indian political parties. Gandhi pushed

through a resolution at the Calcutta Congress in December 1928 calling

on the British government to grant India dominion status or face a new

campaign of non-cooperation with complete independence for the country

as its goal. Gandhi had not only moderated the views of younger men like Subhas Chandra Bose and Jawaharlal Nehru, who sought a demand for immediate independence, but also reduced his own call to a one year wait, instead of two. The

British did not respond. On 31 December 1929, the flag of India was

unfurled in Lahore. 26 January 1930 was celebrated as India's

Independence Day by the Indian National Congress meeting in Lahore.

This day was commemorated by almost every other Indian organization.

Gandhi then launched a new satyagraha against the tax on salt in March

1930. This was highlighted by the famous Salt March to Dandi from 12

March to 6 April, where he marched 388 kilometres (241 miles) from

Ahmedabad to Dandi, Gujarat to make salt himself. Thousands of Indians

joined him on this march to the sea. This campaign was one of his most

successful at upsetting British hold on India; Britain responded by

imprisoning over 60,000 people. The government, represented by Lord Edward Irwin, decided to negotiate with Gandhi. The Gandhi–Irwin Pact was

signed in March 1931. The British Government agreed to free all

political prisoners, in return for the suspension of the civil

disobedience movement. Also as a result of the pact, Gandhi was invited

to attend the Round Table Conference in London as the sole

representative of the Indian National Congress. The conference was a

disappointment to Gandhi and the nationalists, because it focused on

the Indian princes and Indian minorities rather than on a transfer of

power. Furthermore, Lord Irwin's successor, Lord Willingdon,

began a new campaign of controlling and subduing the nationalist

movement. Gandhi was again arrested, and the government tried to negate

his influence by completely isolating him from his followers. But this

tactic failed. In 1932, through the campaigning of the Dalit leader B.R. Ambedkar,

the government granted untouchables separate electorates under the new

constitution. In protest, Gandhi embarked on a six-day fast in

September 1932. The resulting public outcry successfully forced the

government to adopt a more equitable arrangement via negotiations

mediated by the Dalit cricketer turned political leader Palwankar Baloo.

This was the start of a new campaign by Gandhi to improve the lives of

the untouchables, whom he named Harijans, the children of God. On 8 May

1933, Gandhi began a 21-day fast of self-purification to help the

Harijan movement. This new campaign was not universally embraced within the Dalit community, as prominent leader B.R. Ambedkar condemned Gandhi's use of the term Harijans as

saying that Dalits were socially immature, and that privileged caste

Indians played a paternalistic role. Ambedkar and his allies also felt

Gandhi was undermining Dalit political rights. Gandhi, although born

into the Vaishya caste, insisted that he was able to speak on behalf of Dalits, despite the presence of Dalit activists such as Ambedkar. In the summer of 1934, three unsuccessful attempts were made on Gandhi's life. When

the Congress Party chose to contest elections and accept power under

the Federation scheme, Gandhi resigned from party membership. He did

not disagree with the party's move, but felt that if he resigned, his

popularity with Indians would cease to stifle the party's membership,

that actually varied from communists, socialists, trade unionists,

students, religious conservatives, to those with pro-business

convictions and that these various voices would get a chance to make

themselves heard. Gandhi also wanted to avoid being a target for Raj

propaganda by leading a party that had temporarily accepted political

accommodation with the Raj. Gandhi

returned to active politics again in 1936, with the Nehru presidency

and the Lucknow session of the Congress. Although Gandhi wanted a total

focus on the task of winning independence and not speculation about

India's future, he did not restrain the Congress from adopting

socialism as its goal. Gandhi had a clash with Subhas Bose,

who had been elected president in 1938. Their main points of contention

were Bose's lack of commitment to democracy, and lack of faith in

non-violence. Bose won his second term despite Gandhi's criticism, but

left the Congress when the All-India leaders resigned en masse in

protest of his abandonment of the principles introduced by Gandhi.

World War II broke out in 1939 when Nazi Germany invaded Poland.

Initially, Gandhi favoured offering "non-violent moral support" to the

British effort, but other Congressional leaders were offended by the

unilateral inclusion of India in the war, without consultation of the

people's representatives. All Congressmen resigned from office. After

long deliberations, Gandhi declared that India could not be party to a

war ostensibly being fought for democratic freedom, while that freedom

was denied to India itself. As the war progressed, Gandhi intensified

his demand for independence, drafting a resolution calling for the

British to Quit India. This was Gandhi's and the Congress Party's most definitive revolt aimed at securing the British exit from India. Gandhi

was criticized by some Congress party members and other Indian

political groups, both pro-British and anti-British. Some felt that not

supporting Britain more in its life or death struggle against the evil

of Nazism was unethical. Others felt that Gandhi's refusal for India to

participate in the war was insufficient and more direct opposition

should be taken, while Britain fought against Nazism yet continued to

contradict itself by refusing to grant India Independence. Quit India became the most forceful movement in the history of the struggle, with mass arrests and violence on an unprecedented scale. Thousands

of freedom fighters were killed or injured by police gunfire, and

hundreds of thousands were arrested. Gandhi and his supporters made it

clear they would not support the war effort unless India were granted

immediate independence. He even clarified that this time the movement

would not be stopped if individual acts of violence were committed,

saying that the "ordered anarchy" around him was "worse than real anarchy." He called on all Congressmen and Indians to maintain discipline via ahimsa, and Karo Ya Maro ("Do or Die") in the cause of ultimate freedom. Gandhi and the entire Congress Working Committee were arrested in Bombay by the British on 9 August 1942. Gandhi was held for two years in the Aga Khan Palace in Pune. It was here that Gandhi suffered two terrible blows in his personal life. His 50-year old secretary Mahadev Desai died

of a heart attack 6 days later and his wife Kasturba died after 18

months imprisonment in 22 February 1944; six weeks later Gandhi

suffered a severe malaria attack.

He was released before the end of the war on 6 May 1944 because of his

failing health and necessary surgery; the Raj did not want him to die

in prison and enrage the nation. Although the Quit India movement had

moderate success in its objective, the ruthless suppression of the

movement brought order to India by the end of 1943. At the end of the

war, the British gave clear indications that power would be transferred

to Indian hands. At this point Gandhi called off the struggle, and

around 100,000 political prisoners were released, including the

Congress's leadership. As a rule, Gandhi was opposed to the concept of partition as it contradicted his vision of religious unity. Of the partition of India to create Pakistan, he wrote in Harijan on 6 October 1946: [The

demand for Pakistan] as put forth by the Moslem League is un-Islamic

and I have not hesitated to call it sinful. Islam stands for unity and

the brotherhood of mankind, not for disrupting the oneness of the human

family. Therefore, those who want to divide India into possibly warring

groups are enemies alike of India and Islam. They may cut me into

pieces but they cannot make me subscribe to something which I consider

to be wrong [...] we must not cease to aspire, in spite of [the] wild

talk, to befriend all Moslems and hold them fast as prisoners of our

love. However, as Homer Jack notes of Gandhi's long correspondence with Jinnah on

the topic of Pakistan: "Although Gandhi was personally opposed to the

partition of India, he proposed an agreement...which provided that the

Congress and the Moslem League would cooperate to attain independence

under a provisional government, after which the question of partition

would be decided by a plebiscite in the districts having a Moslem

majority." These dual positions on the topic of the partition of India opened Gandhi up to criticism from both Hindus and Muslims. Muhammad Ali Jinnah and contemporary Pakistanis condemned Gandhi for undermining Muslim political rights. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and

his allies accused him of politically appeasing Muslims while turning a

blind eye to their atrocities against Hindus, and for allowing the

creation of Pakistan, despite having publicly declared that "before

partitioning India, my body will have to be cut into two pieces". This continues to be politically contentious: some, like Pakistani-American historian Ayesha Jalal argue that Gandhi and the Congress's unwillingness to share power with the Muslim League hastened partition; others, like Hindu nationalist politician Pravin Togadia indicated that excessive weakness on Gandhi's part led to the division of India. Gandhi also expressed his dislike for partition during the late 1930s in response to the topic of the partition of Palestine to create Israel. He stated in Harijan on 26 October 1938: Several letters have been received by me asking me to declare my views about the Arab-Jew question in Palestine and persecution of the Jews in Germany.

It is not without hesitation that I venture to offer my views on this

very difficult question. My sympathies are all with the Jews. I have

known them intimately in South Africa. Some of them became life-long

companions. Through these friends I came to learn much of their

age-long persecution. They have been the untouchables of Christianity

[...] But my sympathy does not blind me to the requirements of justice.

The cry for the national home for the Jews does not make much appeal to

me. The sanction for it is sought in the Bible and the tenacity with

which the Jews have hankered after return to Palestine. Why should they

not, like other peoples of the earth, make that country their home

where they are born and where they earn their livelihood? Palestine

belongs to the Arabs in the same sense that England belongs to the

English or France to the French. It is wrong and inhuman to impose the

Jews on the Arabs. What is going on in Palestine today cannot be

justified by any moral code of conduct. Gandhi advised the Congress to reject the proposals the British Cabinet Mission offered in 1946, as he was deeply suspicious of the grouping proposed

for Muslim-majority states — Gandhi viewed this as a precursor to

partition. However, this became one of the few times the Congress broke

from Gandhi's advice (though not his leadership), as Nehru and Patel

knew that if the Congress did not approve the plan, the control of

government would pass to the Muslim League.

Between 1946 and 1948, over 5,000 people were killed in violence.

Gandhi was vehemently opposed to any plan that partitioned India into

two separate countries. But an overwhelming majority of Muslims living

in India, alongside Hindus and Sikhs, favoured partition. Additionally Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the leader of the Muslim League, commanded widespread support in West Punjab, Sindh, North-West Frontier Province and East Bengal.

The partition plan was approved by the Congress leadership as the only

way to prevent a wide-scale Hindu-Muslim civil war. Congress leaders

knew that Gandhi would viscerally oppose partition, and it was

impossible for the Congress to go ahead without his agreement, for

Gandhi's support in the party and throughout India was strong. Gandhi's

closest colleagues had accepted partition as the best way out, and Sardar Patel endeavoured to convince Gandhi that it was the only way to avoid civil war. A devastated Gandhi gave his assent. He

conducted extensive dialogue with Muslim and Hindu community leaders,

working to cool passions in northern India, as well as in Bengal. Despite the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, he was troubled when the Government decided to deny Pakistan the 55 crores (550 million Indian rupees) due as per agreements made by the Partition Council. Leaders like Sardar Patel feared

that Pakistan would use the money to bankroll the war against India.

Gandhi was also devastated when demands resurged for all Muslims to be

deported to Pakistan, and when Muslim and Hindu leaders expressed

frustration and an inability to come to terms with one another. Gandhi's arrival in Delhi, turned out to an important intervention in ending the rioting, he even visited Muslims mohallas to restore faith of the Muslim populace. He launched his last fast-unto-death on January 12, 1948, in Delhi, asking

that all communal violence be ended once and for all, Muslims homes be

restored to them and that the payment of 550 million rupees be made to

Pakistan. Gandhi feared that instability and insecurity in Pakistan

would increase their anger against India, and violence would spread

across the borders. He further feared that Hindus and Muslims would

renew their enmity and that this would precipitate open civil war.

After emotional debates with his life-long colleagues, Gandhi refused

to budge, and the Government rescinded its policy and made the payment

to Pakistan. Hindu, Muslim and Sikh community leaders, including the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and Hindu Mahasabha assured him that they would renounce violence and call for peace. Gandhi thus broke his fast by sipping orange juice. On

30 January 1948, Gandhi was shot while he was walking to a platform

from which he was to address a prayer meeting. The assassin, Nathuram Godse, was a Hindu nationalist with links to the extremist Hindu Mahasabha, who held Gandhi responsible for weakening India by insisting upon a payment to Pakistan. Godse and his co-conspirator Narayan Apte were later tried and convicted; they were executed on 15 November 1949. Gandhi's memorial (or Samādhi) at Rāj Ghāt, New Delhi, bears the epigraph "Hē Ram", (Devanagari:हे ! राम or, He Rām),

which may be translated as "Oh God". These are widely believed to be

Gandhi's last words after he was shot, though the veracity of this

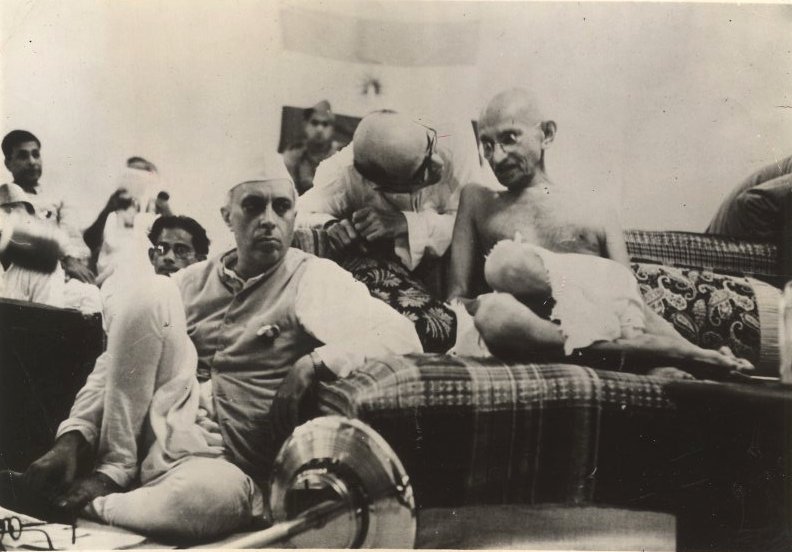

statement has been disputed. Jawaharlal Nehru addressed the nation through radio: "Friends

and comrades, the light has gone out of our lives, and there is

darkness everywhere, and I do not quite know what to tell you or how to

say it. Our beloved leader, Bapu as we called him, the father of the

nation, is no more. Perhaps I am wrong to say that; nevertheless, we

will not see him again, as we have seen him for these many years, we

will not run to him for advice or seek solace from him, and that is a

terrible blow, not only for me, but for millions and millions in this

country." - Jawaharlal Nehru's address to Gandhi Gandhi's ashes were poured into urns which were sent across India for memorial services. Most were immersed at the Sangam at Allahabad on 12 February 1948 but some were secretly taken away. In 1997, Tushar Gandhi immersed the contents of one urn, found in a bank vault and reclaimed through the courts, at the Sangam at Allahabad. On 30 January 2008 the contents of another urn were immersed at Girgaum Chowpatty by the family after a Dubai-based businessman had sent it to a Mumbai museum. Another urn has ended up in a palace of the Aga Khan in Pune (where he had been imprisoned from 1942 to 1944) and another in the Self-Realization Fellowship Lake Shrine in Los Angeles. The

family is aware that these enshrined ashes could be misused for

political purposes but does not want to have them removed because it

would entail breaking the shrines.

In 1915, Gandhi returned from South Africa to live in India. He spoke at the conventions of the Indian National Congress, but was primarily introduced to Indian issues, politics and the Indian people by Gopal Krishna Gokhale, a respected leader of the Congress Party at the time.