<Back to Index>

- Physiologist Otto Heinrich Warburg, 1883

- Painter Ozias Leduc, 1864

- President of Argentina Juan Domingo Perón, 1895

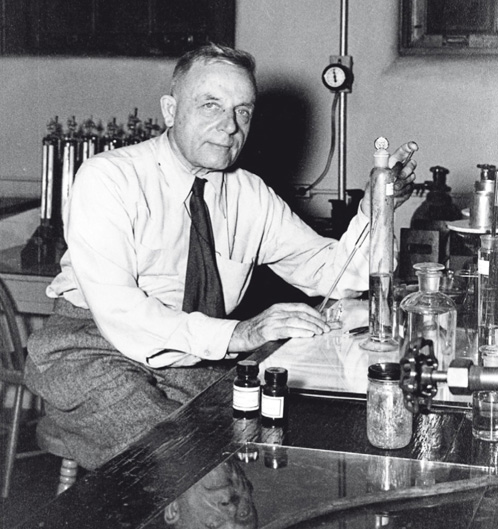

Otto Heinrich Warburg (October 8, 1883, Freiburg im Breisgau – August 1, 1970, Berlin), son of physicist Emil Warburg, was a German physiologist, medical doctor and Nobel laureate. Warburg was one of the twentieth century's leading biochemists.

Otto's father, Emil Warburg, was a distant relative of the illustrious Warburg family of Altona, who had converted to Christianity reportedly after a disagreement in the family. Emil was also President of the Physikalische Reichsanstalt, Wirklicher Geheimer Oberregierungsrat. Otto's mother was the daughter of a Protestant family of civil servants from Baden. Otto studied chemistry under the great Emil Fischer, and earned his Doctorate of Chemistry in Berlin in 1906. He then studied under Ludolf von Krehl, and earned the degree of Doctor of Medicine in Heidelberg in 1911. Between 1908 and 1914, Otto was affiliated with the Naples Marine Biological Station, also known as the Stazione Zoologica, in Naples, Italy, where he did research. In later years he would return for visits, and maintained a lifelong friendship with the family of the station's director.

A lifelong equestrian, he served as an officer in the elite Uhlans (cavalry) on the front during the First World War where he won the Iron Cross.

Warburg later credited this experience with affording him invaluable

insights into "real life" outside the confines of academia. Towards the

end of the war, when the outcome was unmistakable, Albert Einstein,

who had been a friend of Otto's father Emil, wrote Otto at the behest

of friends, asking him to leave the army and return to academia, as it

would be a tragedy for the world to lose his talents. While working at the Marine Biological Station, Warburg performed research on oxygen consumption in sea urchin eggs

after fertilization, and proved that upon fertilization, the rate of

respiration increases by as much as sixfold. His experiments also

proved that iron is essential for the development of the larval stage. In 1918 Warburg was appointed Professor at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology in Berlin-Dahlem (part of the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft). By 1931 he was named Director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Cell Physiology there, which was founded the previous year by a donation of the Rockefeller Foundation to the Kaiser Wilhelm Gesellschaft (since renamed the Max Planck Society). Warburg

investigated the metabolism of tumors and the respiration of cells,

particularly cancer cells, and in 1931 was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his "discovery of the nature and mode of action of the respiratory enzyme." In 1944, Warburg was nominated a second time for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine by Albert Szent-Györgyi, for his work on nicotinamide, the mechanism and enzymes involved in fermentation, and the discovery of flavine (in yellow enzymes). It

is reported by some sources that he was selected to receive the award

that year but was prevented from receiving it by Adolf Hitler’s regime,

which had issued a decree in 1937 that forbade Germans from accepting

Nobel Prizes. According

to the Nobel Foundation, this rumor is not true; although he was

considered a worthy candidate, he was not selected for the prize. Three scientists who worked in Warburg's lab, including Sir Hans Adolf Krebs, went on to win the Nobel Prize. Among other discoveries, Krebs is credited with the identification of the citric acid cycle (or Szentgyörgyi-Krebs cycle). In 1924, Warburg hypothesized that cancer, malignant growth, and tumor growth are caused by the fact that tumor cells mainly generate energy (as e.g. adenosine triphosphate / ATP) by non-oxidative breakdown of glucose (a process called glycolysis). This is in contrast to "healthy" cells which mainly generate energy from oxidative breakdown of pyruvate. Pyruvate is an end-product of glycolysis, and is oxidized within the mitochondria. Hence and according to Warburg, cancer should be interpreted as a mitochondrial dysfunction. "Cancer,

above all other diseases, has countless secondary causes. But, even for

cancer, there is only one prime cause. Summarized in a few words, the prime cause of cancer is the replacement of the respiration of oxygen in normal body cells by a fermentation of sugar." -- Dr. Otto H. Warburg in Lecture. Warburg

continued to develop the hypothesis experimentally, and held several

prominent lectures outlining the theory and the data. The concept that cancer cells switch to glycolysis has become widely accepted, even if it is not seen as the cause of cancer. Some suggest that the Warburg phenomenon could be used to develop anticancer drugs. Meanwhile, cancer cell glycolysis is the basis of positron emission tomography (18-FDG PET), a medical imaging technology that relies on this phenomenon. Otto Warburg edited and has much of his original work published in The Metabolism of Tumours (tr. 1931) and wrote New Methods of Cell Physiology (1962). An unabashed Anglophile, Otto Warburg was thrilled when Oxford University awarded him an honorary doctorate. Otto Warburg was awarded the Order Pour le Mérite in

1952. Warburg was known to tell other universities not to bother with

honorary doctorates, and to ask officials to mail him medals he had

been awarded so as to avoid a ceremony that would separate him from his

beloved laboratory. Warburg

also wrote about oxygen's relationship to the pH of cancer cells

internal environment. Since fermentation was a major metabolic pathway

of cancer cells, Warburg reported that cancer cells maintain a lower

pH, as low as 6.0, due to lactic acid production and elevated CO2.

He firmly believed that there was a direct relationship between pH and

oxygen. Higher pH means higher concentration of oxygen molecules while

lower pH means lower concentrations of oxygen. When frustrated by the lack of acceptance of his ideas, Warburg was known to quote an aphorism he attributed to Max Planck that

science doesn't progress because scientists change their minds, but

rather because scientists attached to erroneous views die, and are

replaced. Seemingly

utterly convinced of the accuracy of his conclusions, Warburg expressed

dismay at the "continual discovery of cancer agents and cancer viruses"

which he expected to "hinder necessary preventative measures and

thereby become responsible for cancer cases". In

his later years Warburg came to be a bit of an eccentric in that he was

convinced that illness resulted from pollution; this caused him to

become a bit of a health advocate. He insisted on eating bread made

from wheat grown organically on land that belonged to him. When he

visited restaurants he often made arrangements to pay the full price

for a cup of tea but to only be served boiling water, from which he

would make tea with a tea bag he had brought with him. He was also

known to go to significant lengths to obtain organic butter whose

quality he trusted. When Dr. Josef Issels,

an intrepid doctor who became famous for his use of non-mainstream

therapies to treat cancer, was arrested and later found guilty of

malpractice in what Issels alleged was a highly politicized case,

Warburg offered to testify on Issels' behalf at his appeal to the

German Supreme Court. All of Issels' convictions were overturned.

The

Otto Warburg Medal is intended to commemorate Warburg's outstanding

achievements. It has been awarded by the German Society for

Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (Gesellschaft für Biochemie und

Molekularbiologie, GBM) since 1963. The prize honors and encourages

pioneering achievements in fundamental biochemical and molecular

biological research. The Otto Warburg Medal is regarded as the highest

award for biochemists and molecular biologists in Germany. It has been

endowed with prize money of 25,000 euros since 2007, sponsored by QIAGEN.