<Back to Index>

- Jurist Hans Kelsen, 1881

- Author François Mauriac, 1885

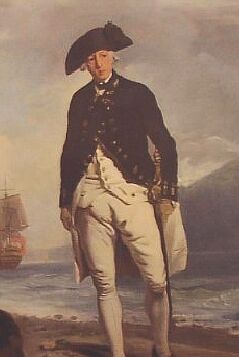

- Governor of New South Wales Admiral Arthur Phillip, 1738

Admiral Arthur Phillip RN (11 October 1738 – 31 August 1814) was a British admiral and colonial administrator. Phillip was appointed Governor of New South Wales, the first European colony on the Australian continent, and was the founder of the site which is now the city of Sydney.

Arthur Phillip was born in Fulham, England in

1738, the son of Jacob Phillip, a German, Frankfurt-born language

teacher, and his English wife, Elizabeth Breach, who had remarried

after the death of her previous husband, a Royal Navy Captain Herbert,

R.N. a collateral descendant of the noble family of Herbert, Earl of

Pembroke. Phillip was educated at the Greenwich Hospital School part of Greenwich Hospital and at the age of 13 was apprenticed to the merchant navy. Phillip joined the Royal Navy at fifteen, and saw action at the outbreak of the Seven Years' War in the Mediterranean at the Battle of Minorca in 1756. In 1762 he was promoted to Lieutenant, but was placed on half pay when the Seven Years War ended in 1763. During this period he married, and farmed in Lyndhurst, Hampshire. In 1774 Phillip joined the Portuguese Navy as a captain, serving in the War against Spain. While with the Portuguese Navy, Phillip commanded a frigate, the Nossa Senhora do Pilar. On

this ship he took a detachment of troops from Rio de Janeiro to Colonia

do Sacramento on the Rio de la Plata (opposite Buenos Aires) to relieve

the garrison there; this voyage also conveyed a consignment of convicts

assigned to carry out work at Colonia. During a storm encountered in

the course of the voyage, the convicts assisted in working the ship

and, on arrival at Colonia, Phillip recommended that they be rewarded

for saving the ship by remission of their sentences. A

garbled version of this eventually found its way into the English press

when Phillip was appointed in 1786 to lead the expedition to Sydney. In 1778 Britain was again at war, and Phillip was recalled to active service, and in 1779 obtained his first command, the Basilisk. He was promoted to captain in 1781, and was given command of the Europe, but in 1784 he was back on half pay. Then, in October 1786, Phillip was appointed captain of HMS Sirius and named Governor-designate of New South Wales, the proposed British penal colony on the east coast of Australia, by Lord Sydney, the Home Secretary. His choice may have been strongly influenced by George Rose,

Under-Secretary of the Treasury and a neighbour of Phillip in Hampshire

who would have known of Phillip's farming experience. Phillip

had a very difficult time assembling the fleet which was to make the

eight-month sea voyage to Australia. Everything a new colony might need

had to be taken, since Phillip had no real idea of what he might find

when he got there. There were few funds available for equipping the

expedition. His suggestion that people with experience in farming,

building and crafts be included was rejected. Most of the 772 convicts

(of whom 732 survived the voyage) were petty thieves from the London

slums. Phillip was accompanied by a contingent of marines and a handful of other officers who were to administer the colony. The First Fleet, of 11 ships, set sail on 13 May 1787. Captain Arthur Phillip collected a number of Cochineal-infested plants from Brazil on his way to establish the first British settlement at Botany Bay. The leading ship, HMS Supply reached Botany Bay setting up camp on the Kurnell Peninsula, on 18 January 1788. Phillip soon decided that this site, chosen on the recommendation of Sir Joseph Banks, who had accompanied James Cook in

1770, was not suitable, since it had poor soil, no secure anchorage and

no reliable water source. After some exploration Phillip decided to go

on to Port Jackson, and on 26 January the marines and convicts were

landed at Sydney Cove,

which Phillip named after Lord Sydney. Shortly after establishing the

settlement at Port Jackson, on 15 February 1788, Phillip sent Lieutenant Philip Gidley King with

8 free men and a number of convicts to establish the second British

colony in the Pacific at Norfolk Island. This was partly in response to

a perceived threat of losing Norfolk Island to the French and partly to

establish an alternative food source for the new colony. The

early days of the settlement were chaotic and difficult. With limited

supplies, the cultivation of food was imperative, but the soils around

Sydney were poor, the climate was unfamiliar, and moreover very few of

the convicts had any knowledge of agriculture. Farming tools were scarce and the convicts were unwilling farm labourers. The colony was on the verge of outright starvation for

an extended period. The marines, poorly disciplined themselves in many

cases, were not interested in convict discipline. Almost at once,

therefore, Phillip had to appoint overseers from among the ranks of the

convicts to get the others working. This was the beginning of the

process of convict emancipation which was to culminate in the reforms of Lachlan Macquarie after 1811. Phillip showed in other ways that he recognised that New South Wales could

not be run simply as a prison camp. Lord Sydney, often criticised as an

ineffectual incompetent, had made one fundamental decision about the

settlement that was to influence it from the start. Instead of just

establishing it as a military prison, he provided for a civil

administration, with courts of law. Two convicts, Henry and Susannah Kable, sought to sue Duncan Sinclair, the captain of Alexander,

for stealing their possessions during the voyage. Convicts in Britain

had no right to sue, and Sinclair had boasted that he could not be sued

by them. Someone in Government obviously had a quiet word in Kable's

ear, as when the court met and Sinclair challenged the prosecution on

the ground that the Kables were felons, the court required him to prove

it. As all the convict records had been left behind in England, he

could not do so, and the court ordered the captain to make restitution.

Phillip had said before leaving England: "In a new country there will

be no slavery and hence no slaves," and he meant what he said.

Nevertheless, Phillip believed in discipline, and floggings and

hangings were commonplace, although Philip commuted many death

sentences. Phillip also had to adopt a policy towards the Eora Aboriginal people, who lived around the waters of Sydney Harbour.

Phillip ordered that they must be well-treated, and that anyone killing

Aboriginal people would be hanged. Phillip befriended an Eora man called Bennelong, and later took him to England. On the beach at Manly,

a misunderstanding arose and Phillip was speared in the shoulder: but

he ordered his men not to retaliate. Phillip went some way towards

winning the trust of the Eora, although the settlers were at all times

treated extremely warily. Soon, smallpox and other European-introduced epidemics ravaged the Eora population. The

Governor's main problem was with his own military officers, who wanted

large grants of land, which Phillip had not been authorised to grant.

The officers were expected to grow food, but they considered this

beneath them. As a result scurvy broke out, and in October 1788 Phillip had to send Sirius to Cape Town for supplies, and strict rationing was introduced, with thefts of food punished by hanging. By 1790 the situation had stabilised. The population of about 2,000 was

adequately housed and fresh food was being grown. Phillip assigned a

convict, James Ruse, land at Rose Hill (now Parramatta)

to establish proper farming, and when Ruse succeeded he received the

first land grant in the colony. Other convicts followed his example. Sirius was wrecked in March 1790 at the satellite settlement of Norfolk Island, depriving Phillip of vital supplies. In June 1790 the Second Fleet arrived with hundreds more convicts, most of them too sick to work. By

December 1790 Phillip was ready to return to England, but the colony

had largely been forgotten in London and no instructions reached him,

so he carried on. In 1791 he was advised that the government would send

out two convoys of convicts annually, plus adequate supplies. But July,

when the vessels of the Third Fleet began to arrive, with 2,000 more convicts, food again ran short, and he had to send a ship to Calcutta for supplies. By 1792 the colony was well-established, though Sydney remained an unplanned huddle of wooden huts and tents. The whaling industry was established, ships were visiting Sydney to trade, and convicts whose sentences had expired were taking up farming. John Macarthur and

other officers were importing sheep and beginning to grow wool. The

colony was still very short of skilled farmers, craftsmen and

tradesmen, and the convicts continued to work as little as possible,

even though they were working mainly to grow their own food. In

late 1792 Phillip, whose health was suffering from the poor diet, at

last received permission to leave, and on 11 December 1792 he sailed in

the ship Atlantic,

taking with him many specimens of plants and animals. He also took

Bennelong and his friend Yemmerrawanyea, another young Indigenous

Australian who, unlike Bennelong, would succumb to English weather and

disease and not live to make the journey home. The European population

of New South Wales at his departure was 4,221, of whom 3,099 were

convicts. The early years of the colony had been years of struggle and

hardship, but the worst was over, and there were no further famines in

New South Wales. Phillip arrived in London in May 1793. He tendered his

formal resignation and was granted a pension of £500 a year. Phillip's wife, Margaret, had died in 1792. In 1794 he married Isabella Whitehead, and lived for a time at Bath.

His health gradually recovered and in 1796 he went back to sea, holding

a series of commands and responsible posts in the wars against the

French. In January 1799 he became a Rear-Admiral. In 1805, aged 67, he

retired from the Navy with the rank of Admiral of the Blue,

and spent most of the rest of his life at Bath. He continued to

correspond with friends in New South Wales and to promote the colony's

interests with government officials. He died in Bath in 1814. Phillip was buried in St Nicholas's Church, Bathampton. Forgotten for many years, the grave was discovered in 1897 and the Premier of New South Wales, Sir Henry Parkes, had it restored. An annual service of remembrance is held here around Phillip's birthdate by the Britain-Australia Society to commemorate his life. A monument to Phillip in Bath Abbey Church

was unveiled in 1937. Another was unveiled at St Mildred's Church,

Bread St, London, in 1932; that church was destroyed in the London Blitz in 1940, but the principal elements of the monument were re-erected in St Mary-le-Bow at the west end of Watling Street, near Saint Paul's Cathedral, in 1968. There is a statue of him in the Botanic Gardens, Sydney. There is a portrait in the National Portrait Gallery, London. His name is commemorated in Australia by Port Phillip, Phillip Island (Victoria), Phillip Island (Norfolk Island), the federal electorate of Phillip (1949-1993), the suburb of Phillip in Canberra, and many streets, parks and schools. Note: Port Arthur, Tasmania is not named after Arthur Phillip. Percival Alan Serle wrote of Phillip in the Dictionary of Australian Biography:

"Steadfast in mind, modest, without self seeking, Phillip had

imagination enough to conceive what the settlement might become, and

the common sense to realize what at the moment was possible and

expedient. When almost everyone was complaining he never himself

complained, when all feared disaster he could still hopefully go on

with his work. He was sent out to found a convict settlement, he laid

the foundations of a great dominion."

In 2007, Geoffrey Robertson QC alleged

that Phillip's remains are no longer in St Nicholas Church, Bathampton

and have been lost: "...Captain Arthur Phillip is not where the ledger

stone says he is: it may be that he is buried somewhere outside, it may

simply be that he is simply lost. But he is not where Australians have

been led to believe that he now lies." Robertson also believes it was a "disgraceful slur" on Phillip's legacy that he was not buried in one of England's great cathedrals and

was relegated to a small village church. Robertson is campaigning for a

rigorous search for the remains, which he believes should be

re-interred in Australia.