<Back to Index>

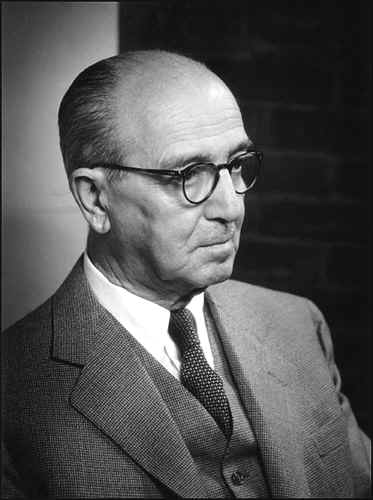

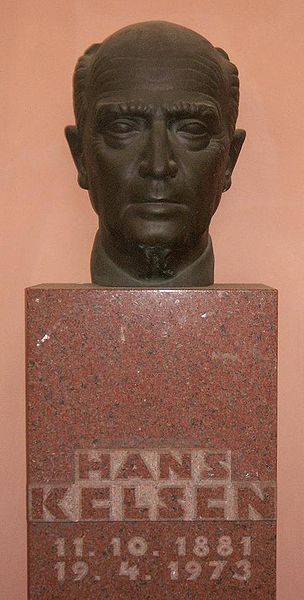

- Jurist Hans Kelsen, 1881

- Author François Mauriac, 1885

- Governor of New South Wales Admiral Arthur Phillip, 1738

Hans Kelsen (October 11, 1881 – April 19, 1973) was an Austrian American jurist and legal philosopher. He has been regarded as one of the most important German-speaking legal scholars of the 20th century.

Kelsen was born in Prague to Jewish parents. He moved to Vienna with his family when he was two years old. Having graduated from the Akademisches Gymnasium, he studied law at the University of Vienna, taking his doctorate in 1906. In 1911, he achieved his habilitation (license to hold university lectures) in public law and legal philosophy and published his first major work, Main Problems in the Theory of Public Law (Hauptprobleme der Staatsrechtslehre).

In 1912, Kelsen married Margarete Bondi, and the couple had two daughters.

In 1919, he became full professor of public and administrative law at the University of Vienna. He established and edited the Journal of Public Law (Zeitschrift für Öffentliches Recht) in Vienna. At the behest of Chancellor Karl Renner, Kelsen worked on drafting a new Austrian Constitution, enacted in 1920. The document still forms the basis of Austrian constitutional law. Kelsen was appointed to the Constitutional Court, for a life term. In 1925, he published General Theory of the State (Allgemeine Staatslehre) in Berlin. Following increasing political controversy about some positions of the Constitutional Court (especially about divorce) and an increasingly conservative climate, Kelsen, who was considered a Social Democrat, although not a party member, was removed from the court in 1930. Kelsen accepted a professorship at the University of Cologne in 1930. When the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, he was removed from his post and moved to Geneva, Switzerland and taught international law at the Graduate Institute of International Studies from 1934 to 1940.

In 1934, he published the first edition of Pure Theory of Law (Reine Rechtslehre). In Geneva he became more interested in international law. In 1936–1938 he was professor at the German University in Prague.

In 1940, he moved to the United States, giving the Oliver Wendell Holmes Lectures at Harvard Law School in 1942 and becoming a full professor at the department of political science at the University of California, Berkeley in 1945. During those years, he increasingly dealt with issues of international law and international institutions such as the United Nations. In 1953-54, he was visiting Professor of International Law at the United States Naval War College.

Kelsen's main legacy is as the inventor of the modern European model of constitutional review, first used in the Austrian First Republic, then in the Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal,

and later many countries of Central and Eastern Europe. The Kelsenian

court model sets up separate constitutional courts, which may have sole

responsibility over constitutional disputes within the judicial system;

this is different from the American system in which courts of general

jurisdiction from the trial level to the court of last resort

frequently have powers of judicial review. Kelsen

is considered one of the preeminent jurists of the 20th century. His

legal theory, a very strict and scientifically understood type of legal positivism, is based on the idea of a Grundnorm, a hypothetical norm on which all subsequent levels of a legal system such as constitutional law and "simple" law are based. His theory has followers among scholars of public law worldwide. His disciples developed "schools" of thought to extend his theories, such as the Vienna School in Austria and the Brno School in Czechoslovakia. In the English-speaking world, H.L.A. Hart and Joseph Raz are

perhaps the most well-known authors who were influenced by Kelsen,

though both departed from Kelsen's theories in several respects. Kelsen's was a negative influence on Carl Schmitt, who criticized Kelsen's work on sovereignty in Political Theology and

elsewhere. In turn, Kelsen wrote that only the belief in a "theology of

the State" could justify the refusal to acknowledge the binding nature

of international law upon "sovereign" states. For Kelsen, "sovereignty"

was a loaded concept: "We can derive from the concept of sovereignty

nothing else than what we have purposely put into its definition."