<Back to Index>

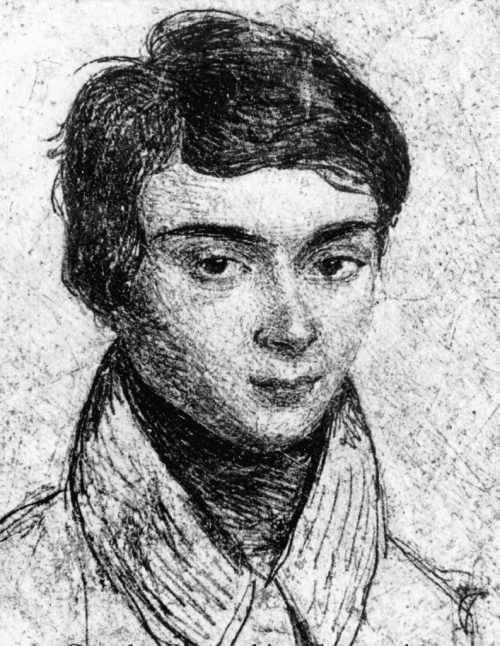

- Mathematician Évariste Galois, 1811

- Composer Johann Baptist Strauss II, 1825

- 3rd Prime Minister of Israel Levi Eshkol, 1895

PAGE SPONSOR

Évariste Galois (October 25, 1811 – May 31, 1832) was a French mathematician born in Bourg-la-Reine. While still in his teens, he was able to determine a necessary and sufficient condition for a polynomial to be solvable by radicals, thereby solving a long-standing problem. His work laid the foundations for Galois theory, a major branch of abstract algebra, and the subfield of Galois connections. He was the first to use the word "group" (French: groupe) as a technical term in mathematics to represent a group of permutations. A radical Republican during the monarchy of Louis Philippe in France, he died from wounds suffered in a duel under shadowy circumstances at the age of twenty.

Galois was born on October 25, 1811, to Nicolas-Gabriel Galois and Adélaïde-Marie (born Demante). His father was a Republican and was head of Bourg-la-Reine's liberal party. He became mayor of the village after Louis XVIII returned to the throne in 1814. His mother, the daughter of a jurist, was a fluent reader of Latin and classical literature and she was responsible for her son's education for his first twelve years. At the age of 10, Galois was offered a place at the college of Reims, but his mother preferred to keep him at home. In October 1823, he entered the Lycée Louis-le-Grand,

and despite some turmoil in the school at the beginning of the term

(where about a hundred students were expelled), Galois managed to

perform well for the first two years, obtaining the first prize in

Latin. He soon became bored with his studies, and at the age of 14, he

began to take a serious interest in mathematics. He found a copy of Adrien Marie Legendre's Éléments de Géométrie, which it is said that he read "like a novel" and mastered at the first reading. At 15, he was reading the original papers of Joseph Louis Lagrange, such as the landmark Réflexions sur la résolution algébrique des équations which likely motivated his later work on equation theory, and Leçons sur le calcul des fonctions, work intended for professional mathematicians, yet his classwork remained uninspired, and his teachers accused him of affecting ambition and originality in a negative way. In 1828, he attempted the entrance exam to École Polytechnique,

the most prestigious institution for mathematics in France at the time,

without the usual preparation in mathematics, and failed for lack of

explanations on the oral examination. In that same year, he entered the École Normale (then

known as l'École préparatoire), a far inferior

institution for mathematical studies at that time, where he found some

professors sympathetic to him. In the following year, Galois' first paper, on continued fractions, was published. It was at around the same time that he began making fundamental discoveries in the theory of polynomial equations. He submitted two papers on this topic to the Academy of Sciences. Augustin Louis Cauchy refereed

these papers, but refused to accept them for publication for reasons

that still remain unclear. However, in spite of many claims to the

contrary, it appears that Cauchy recognized the importance of Galois'

work, and that he merely suggested combining the two papers into one in

order to enter it in the competition for the Academy's Grand Prize in

Mathematics. Cauchy, a highly eminent mathematician of the time

considered Galois' work to be a likely winner. On July 28, 1829, Galois' father committed suicide after

a bitter political dispute with the village priest. A couple of days

later, Galois took his second, and final attempt at entering the

Polytechnique, and failed yet again. It is undisputed that Galois was

more than qualified; however, accounts differ on why he failed. The

legend holds that he thought the exercise proposed to him by the

examiner to be of no interest, and, in exasperation, he threw the rag

used to clean up chalk marks on the blackboard at the examiner's head. More

plausible accounts state that Galois made too many logical leaps and

baffled the incompetent examiner, evoking irascible rage in Galois. The

recent death of his father may have also influenced his behavior. Having been denied admission to the Polytechnique, Galois took the Baccalaureate examinations in order to enter the Ecole Normale.

He passed, receiving his degree on December 29, 1829. His examiner in

mathematics reported, "This pupil is sometimes obscure in expressing

his ideas, but he is intelligent and shows a remarkable spirit of

research." His

memoir on equation theory would be submitted several times, but was

never published in his lifetime due to various events. As noted before,

his first attempt was refused by Cauchy, but he tried again in February

1830 after following Cauchy's suggestions and submitted it to the

Academy's secretary Fourier,

to be considered for the Grand Prix of the Academy. Unfortunately,

Fourier died soon after, and the memoir was lost. The prize would be

awarded that year to Abel posthumously and also to Jacobi. Despite the lost memoir, Galois published three papers that year, two of which laid the foundations for Galois theory, and the third, an important one on number theory, where the concept of a finite field was first articulated. Galois lived during a time of political turmoil in France. Charles X had

succeeded Louis XVIII in 1824, but in 1827 his party suffered a major

electoral setback and by 1830 the opposition liberal party became the

majority. Charles, faced with abdication, staged a coup d'état,

and issued his notorious July Ordinances, touching off the July Revolution which ended with Louis-Philippe becoming king. While their counterparts at Polytechnique were making history in the streets during the les Trois Glorieuses,

Galois and all the other students at the École Normale were

locked in by the school's director. Galois was incensed and he wrote a

blistering letter criticizing the director which he submitted to the Gazette des Écoles, signing the letter with his full name. Despite the fact that the Gazette's editor redacted the signature for publication, Galois was, predictably, expelled for it. Although

his expulsion would have formally taken effect on January 4, 1831,

Galois quit school immediately and joined the staunchly Republican

artillery unit of the National Guard.

These and other political affiliations continually distracted him from

mathematical work. Due to controversy surrounding the unit, soon after

Galois became a member, on December 31, 1830, the artillery of the

National Guard was disbanded out of fear that they might destabilize

the government. At around the same time, nineteen officers of Galois'

former unit were arrested and charged with conspiracy to overthrow the

government. In

April, the nineteen officers were acquitted of all charges, and on May

9, 1831, a banquet was celebrated in their honor, with many illustrious

people present, such as Alexandre Dumas. The proceedings became more riotous, and Galois proposed a toast to

King Louis-Philippe with a dagger above his cup, which was interpreted

as a threat against the king's life. He was arrested the following day,

but was acquitted on June 15. On the following Bastille Day,

Galois was at the head of a protest, wearing the uniform of the

disbanded artillery, and came heavily armed with several pistols, a

rifle, and a dagger. For this, he was again arrested and this time

sentenced to six months in prison for illegally wearing a uniform. He was released on April 29, 1832. During his imprisonment, he continued developing his mathematical ideas. Galois

returned to mathematics after his expulsion from the École

Normale, although he was constantly distracted by his political

activities. After his expulsion became official in January 1831, he

attempted to start a private class in advanced algebra which did manage

to attract a fair bit of interest, but this waned, as it seemed that his political activism had priority. Simeon Poisson asked him to submit his work on the theory of equations,

which he did on January 17. Around July 4, Poisson declared Galois'

work "incomprehensible", declaring that "[Galois'] argument is neither

sufficiently clear nor sufficiently developed to allow us to judge its

rigor"; however, the rejection report ends on an encouraging note: "We

would then suggest that the author should publish the whole of his work

in order to form a definitive opinion." While

Poisson's report was made before Galois' Bastille Day arrest, it took

some time for it to reach Galois, which it finally did in October that

year, while he was imprisoned. It is unsurprising, in the light of his

character and situation at the time, that Galois reacted violently to

the rejection letter,

and he decided to forget about having the Academy publish his work, and

instead publish his papers privately through his friend Auguste

Chevalier. Apparently, however, Galois did not ignore Poisson's advice

and began collecting all his mathematical manuscripts while he was

still in prison, and continued polishing his ideas until his release on

April 29, 1832. Galois'

fatal duel took place on May 30. The true motives behind the duel will

most likely remain forever obscure. There has been a lot of

speculation, much of it spurious, as to the reasons behind it. What is

known is that five days before his death, he wrote a letter to

Chevalier which clearly alludes to a broken love affair. Some

archival investigation on the original letters reveals that the woman he was in love with was apparently a certain Mademoiselle Stéphanie-Felicie Poterin du Motel,

the daughter of the physician at the hostel where Galois remained

during the final months of his life. Fragments of letters from her

copied by Galois himself (with many portions either obliterated, such

as her name, or deliberately omitted) are available. The

letters give some intimation that Mlle. du Motel had confided some of

her troubles with Galois, and this might have prompted him to provoke

the duel himself on her behalf. This conjecture is also supported by

some of the other letters Galois later wrote to his friends the night

before he died. Much more detailed speculation based on these scant

historical details has been interpolated by many of Galois' biographers (most notably by Eric Temple Bell in Men of Mathematics),

such as the oft-repeated conjecture that the entire incident was

stage-managed by the police and royalist factions to eliminate a

political enemy. As

to his opponent in the duel, Alexandre Dumas names Pescheux

d'Herbinville, one of the nineteen artillery officers on whose

acquittal the banquet that occasioned Galois' first arrest was

celebrated and du Motel's fiancee. However,

Dumas is alone in this assertion, and extant newspaper clippings from

only a few days after the duel give a description of his opponent which

is inconsistent with d'Herbinville, and more accurately describes one

of Galois' Republican friends, most probably Ernest Duchatelet, who was

also imprisoned with Galois on the same charges. Given the conflicting

information available, the true identity of his killer may well be lost

to history. Whatever

the reasons behind the duel, Galois was so convinced of his impending

death that he stayed up all night writing letters to his Republican

friends and composing what would become his mathematical testament, the

famous letter to Auguste Chevalier outlining his ideas. Hermann Weyl,

one of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century, said of this

testament, "This letter, if judged by the novelty and profundity of

ideas it contains, is perhaps the most substantial piece of writing in

the whole literature of mankind." However, the legend of Galois pouring

his mathematical thoughts onto paper the night before he died seems to

have been exaggerated. In these final papers, he outlined the rough

edges of some work he had been doing in analysis and annotated a copy

of the manuscript submitted to the Academy and other papers. Early in the morning of May 30, 1832, he was shot in the abdomen and died the following day at ten in the Cochin hospital (probably of peritonitis) after refusing the offices of a priest. He was 20 years old. His last words to his brother Alfred were: Ne pleure pas, Alfred ! J'ai besoin de tout mon courage pour mourir à vingt ans ! (Don't cry, Alfred! I need all my courage to die at twenty.) On June 2, Évariste Galois was buried in a common grave of the Montparnasse cemetery whose exact location is unknown. In the cemetery of his native town - Bourg-la-Reine - a cenotaph in his honour was erected beside the graves of his relatives. Much of the drama surrounding the legend of his death has been attributed to one source, Eric Temple Bell's Men of Mathematics. Galois' mathematical contributions were published in full in 1843 when Liouville reviewed his manuscript and declared it sound. It was finally published in the October–November 1846 issue of the Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées. The most famous contribution of this manuscript was a novel proof that there is no quintic formula, that is, that fifth and higher degree equations are not solvable by radicals. Although Abel had already proved the impossibility of a "quintic formula" by radicals in 1824 and Ruffini had

published a solution in 1799 that turned out to be flawed, Galois'

methods led to deeper research in what is now called Galois theory. For

example, one can use it to determine, for any polynomial equation, whether it has a solution by radicals. Après cela, il y aura, j'espere, des gens qui trouveront leur profit à déchiffrer tout ce gâchis. (Ask

Jacobi or Gauss publicly to give their opinion, not as to the truth,

but as to the importance of these theorems. Later there will be, I

hope, some people who will find it to their advantage to decipher all

this mess.) —Évariste Galois, Lettre de Galois à M. Auguste Chevalier Unsurprisingly,

Galois' collected works amount to only some 60 pages, but within them

are many important ideas that have had far-reaching consequences for

nearly all branches of mathematics. His work has been compared to that of Niels Henrik Abel, another mathematician who died at a very young age, and much of their work had significant overlap.

While many mathematicians before Galois gave consideration to what are now known as groups, it was Galois who was the first to use the word 'group' (in French groupe)

in a sense close to the technical sense that is understood today,

making him among the key founders of the branch of algebra known as group theory. He developed the concept that is today known as a normal subgroup. He called the decomposition of a group into its left and right cosets a 'proper decomposition' if the left and right cosets coincide, which is what today is known as a normal subgroup. He also introduced the concept of a finite field (also known as a Galois field in his honor), in essentially the same form as it is understood today.

Galois'

most significant contribution to mathematics by far is his development

of Galois theory. He realized that the algebraic solution to a polynomial equation is related to the structure of a group of permutations associated with the roots of the polynomial, the Galois group of the polynomial. He found that an equation could be solvable in radicals if one can find a series of subgroups of its Galois group, each one normal its successor with abelian quotient, or its Galois group is solvable. This proved to be a fertile approach, which later mathematicians adapted to many other fields of mathematics besides the theory of equations which Galois originally applied it to.

“ Tu

prieras publiquement Jacobi ou Gauss de donner leur avis, non sur la

vérité, mais sur l'importance des théorèmes. ”