<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Ferdinand Georg Frobenius, 1849

- Composer Giuseppe Domenico Scarlatti, 1685

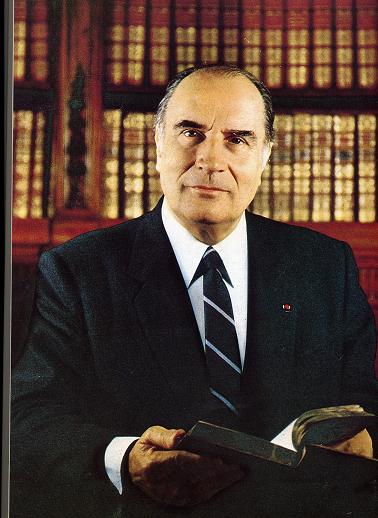

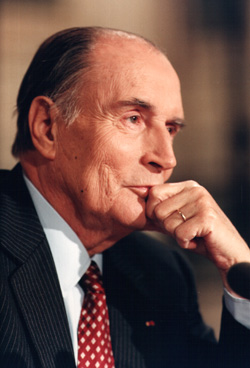

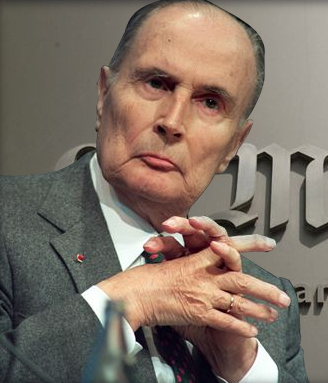

- Président de la République Française François Maurice Adrien Marie Mitterrand, 1916

PAGE SPONSOR

François Maurice Adrien Marie Mitterrand (26 October 1916 – 8 January 1996) was the 21st President of the French Republic, serving from 1981 until 1995, and the candidate of the left in each presidential election of the Fifth Republic from 1965 - 1988 (excepting 1969).

First elected during the May 1981 presidential election, he became the first socialist President of the Fifth Republic and the first left-wing head of state since 1957. He is to date the only member of the Socialist Party to be elected as the President of France. He was re-elected in 1988 and held office until 1995, before his death from prostate cancer the

following year. At the beginning of each of his two terms, he dissolved

the Parliament and held a fresh legislative election in the hope that

the Socialist Party would win and he would have a parliamentary

majority. This did indeed happen as he hoped; however, both times, his

party lost the next legislative elections. He was consequently forced

into "cohabitation governments" during the two last years of each of his terms with conservative cabinets. They were led by Jacques Chirac from 1986 until 1988, and by Édouard Balladur from 1993 to 1995. As of 2010 Mitterrand

holds the record of the longest-serving (almost 14 years) President of France. He was also the oldest President of the Fifth Republic, leaving office aged 78 years and seven months. He died on January 8, 1996 after returning from a Christmas holiday in Egypt. Mitterrand was born in Jarnac, Charente, and baptized as François Maurice Adrien Marie Mitterrand. His family was a devoutly Roman Catholic one and very conservative. His father, Joseph Gilbert Félix, worked as an engineer for la Compagnie Paris Orléans and

his maternel grandfather, Jules Lorrain, worked as a vinegar-maker and

later served as the president of the federation of vinegar-makers union (Fédération des syndicats de fabricants de vinaigre). Joseph's maternal grandmother, Marguerite du Soulier de Clareuil, was a noblewoman and a descendant of both Fernando III of Castile and Jean de Brienne of Jerusalem. Mitterrand's mother was Marie Gabrielle Yvonne Lorrain, a remote niece of Pope John XXII by

a genealogical link with the lords de Barbezières. He had three

brothers (Robert, Jacques and Philippe) and four sisters. His wife, Danielle Mitterrand née Gouze, came from a socialist background and has worked for various left-wing causes. They married on 24 October 1944 and had three sons: Pascal (10 June 1945 – 17 September 1945), Jean-Christophe, born in 1946, and Gilbert Mitterrand born on 4 February 1949. He also had a daughter, Mazarine born in 1974, with Anne Pingeot. His nephew Frédéric Mitterrand is a journalist, currently the Minister of Culture and Communications (and a supporter of Jacques Chirac, the former president of France), and his brother-in-law Roger Hanin is a well-known French actor. Mitterrand studied from 1925 to 1934 in the collège Saint-Paul in Angoulême, where he became a member of the JEC (Jeunesse étudiante chrétienne), the student organisation of Action catholique. Arriving in Paris in autumn 1934, he then went to the École Libre des Sciences Politiques until 1937, where he obtained his diploma in July of that year. Mitterrand took membership for about a year in the Volontaires nationaux (National Volunteers), an organisation related to François de la Rocque's far-right league, the Croix de Feu; the league had just participated in the 6 February 1934 riots which led to the fall of the second Cartel des Gauches (Left-Wing Coalition). Contrary to what has been said, he never took his card at the Parti Social Français (PSF) which succeeded to the Croix de Feu and may be considered as the first French right-wing mass party. However, he did write news articles in the L'Echo de Paris newspaper, close to the PSF. He participated in the xenophobic demonstrations against the "métèque invasion" in February 1935 and then in those against law teacher Gaston Jèze, who had been nominated as juridical counsellor of Ethiopia's Negus, in January 1936. When his involvement in these nationalist movements was discovered in the 1990s, he attributed his actions to the milieu of

his youth. Mitterrand furthermore had some personal and family

relations with members of the Cagoule, a far-right terrorist group in the 1930s. In a logical way for his then nationalist ideas, he was disturbed by Nazi expansionism during the Anschluss. Mitterrand then served his conscription from 1937 to 1939 in the 23rd régiment d'infanterie coloniale. In 1938, he became the best friend of Georges Dayan, a Jewish socialist, whom he saved from anti-Semite aggressions by the national-royalist movement Action française. His

friendship with Dayan caused Mitterrand to begin to question his

nationalist ideas. Finishing his law studies, he was sent to the Maginot line in September 1939, with the rank of Sergeant-chief (infantry sergeant), near Montmédy. He became engaged to Marie-Louise Terrasse (future actress Catherine Langeais) in May 1940 (but she broke it off in January 1942). François Mitterrand's actions during World War II were the cause of much controversy in France in the 1980s and 1990s. Mitterrand

was at the end of his national service when the war broke out. He

fought as an infantry sergeant and was injured and captured by the

Germans on 14 June 1940. He was held prisoner at Stalag IXA near Ziegenhain (today called Trutzhain, a village near Kassel in Hesse).

Mitterrand became involved in the social organisation for the POWs in

the camp. He claims this, and the influence of the people he met there,

began to change his political ideas, moving them towards the left. He

had two failed escape attempts in March and then November of 1941

before he finally escaped on 10 December 1941, returning to France on

foot. In December 1941 he arrived home in the unoccupied zone

controlled by the French. With help from a friend of his mother he got

a job as a mid-level functionary of the Vichy government, looking after the interests of POWs. This was very unusual for an escaped prisoner, and he later claimed to have served as a spy for the Free French Forces. Mitterrand worked from January to April 1942 for the Légion française des combattants et des volontaires de la révolution nationale (Legion

of French combatants and volunteers of the national revolution) as a

civil servant on a temporary contract. He worked under Favre de Thierrens who was a spy for the British secret service. He then moved to the Commissariat au reclassement des prisonniers de guerre (Service

for the orientation of POWS). During this period, Mitterrand was aware

of Thierrens's activities and may have helped in his disinformation

campaign. At the same time, he published an article detailing his time as a POW in the magazine France, revue de l'État nouveau (the magazine was published as propaganda by the Vichy Regime). Mitterrand

has been called a "Vichysto-résistant" (an expression used by

the historian Jean-Pierre Azéma to describe people who supported Philippe Pétain before 1943, but subsequently rejected the Vichy Regime). From spring 1942, he met other escaped POWs Jean Roussel, Max Varenne, and Dr. Guy Fric,

under whose influence he became involved with the resistance. In April,

Mitterrand and Fric caused a major disturbance in a public meeting held

by the collaborator Georges Claude.

From mid-1942, he sent false papers to POWs in Germany and on 12 June

and 15 August 1942, he joined meetings at the Château de Montmaur

which formed the base of his future network for the resistance. From September, he made contact with France libre, but failed to get on with Michel Cailliau, General Charles de Gaulle's nephew. On 15 October 1942, Mitterrand and Marcel Barrois (a member of the resistance deported in 1944) met Maréchal Philippe Pétain along with other members of the Comité d'entraide aux prisonniers rapatriés de l'Allier (Help group for repatriated POWs in the department of Allier). By the end of 1942, Mitterrand met up with an old friend from his days with the "Cagoule" Pierre Guillain de Bénouville. Bénouville was a member of the resistance groups Combat and Noyautage des administrations publiques (NAP). In late 1942, the non-occupied zone was invaded by the Germans. Mitterrand left the Commissariat in January 1943, when his boss Maurice Pinot, another vichysto-résistant, was replaced by the collaborator André Masson, but he remained in charge of the centres d'entraides. In the spring of 1943, along with Gabriel Jeantet, a member of Maréchal Pétain's cabinet, and Simon Arbellot (both former members of "la Cagoule"), Mitterrand received the Ordre de la francisque (the

honorific distinction of the Vichy Regime). Debate rages in France as

to the significance of this. When Mitterrand's Vichy past was exposed

in the 1950s, he initially denied having received the Francisque (some

sources say he was designated for the award, but never actually

received the medal because he went into hiding before the ceremony

could take place). Some say he was ordered to accept the medal as cover for his work in the resistance. Others, such as Pierre Moscovici and Jacques Attali remain

sceptical of Mitterrand's true beliefs at this time, accusing him of

having at best a "foot in each camp" until he was sure who the winner

would be, citing Mitterrand friendship with René Bousquet and the wreaths he placed on Pétain's tomb as examples of his ambivalent attitude. Mitterrand set about building up a resistance network, composed mainly of former POWs like himself. The POWs National Rally (Rassemblement national des prisonniers de guerre or RNPG) was affiliated with General Henri Giraud,

a former POW who had escaped from a German prison and made his way

across Germany back to the Allied forces. Giraud was then contesting

the leadership of the French Resistance with General Charles de Gaulle. From the beginning of 1943, Mitterrand became involved with setting up a powerful resistance group called the Organisation de résistance de l'armée (ORA).

He obtained finance for his own RNPG network, which he set up with

Pinot in February. From this time on, Mitterrand was a member of the

ORA. In March, Mitterrand met Henri Frenay, who encouraged the resistance in France to support Mitterrand over Michel Cailliau, but 28 May 1943, when Mitterrand met with Gaullist Philippe Dechartre, is generally taken as the date Mitterrand split with Vichy. During 1943, the RNPG gradually changed its focus from providing false papers to information-gathering for France libre.

Pierre de Bénouville said, " Mitterrand created a true spy

network in the POW camps which gave us information, often decisive,

about what was going on behind the German borders." On

10 July Mitterrand and Piatzook (a militant communist) interrupted a

public meeting at in the Salle Wagram in Paris. The meeting was about

allowing French POWs to go home if they were replaced by young French

men forced to go and work in Germany" (in French this is called "la

relève"). When André Masson began to talk about "la

trahison des gaullistes" (the Gaulist treason), Mitterrand stood up in

the audience and shouted him down, saying Masson had no right to talk

on behalf of POWs and calling "la relève" a con. Mitterrand

avoided arrest as Piatzook covered his escape. In November 1943 the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) raided a flat in Vichy where they hoped to arrest François Morland, a member of the resistance. "Morland"

was Mitterrand's cover name. He also used Purgon, Monnier, Laroche,

capitaine François, Arnaud et Albre as cover names. The man they

arrested was Pol Pilven,

a member of the resistance who was to survive the war in a

concentration camp. Mitterrand was in Paris at the time. Warned by his

friends, he escaped to London aboard a Lysander plane on 15 November 1943. From there he went to Algiers, where he met Charles de Gaulle,

who was now the uncontested leader of the Free French. The two men did

not get along. Mitterrand refused to merge his group with other POW

movements if Cailliau was to be the leader. Under

the influence of Henri Frenay, de Gaulle finally agreed to merge his

nephew's network and the RNPG with Mitterrand in charge. He

later returned to France via England by boat. In Paris, the three

Resistance groups made up of POWs (communists, gaullists, RNPG) finally

merged as the POWs and Deportees National Movement (Mouvement national des prisonniers de guerre et déportés or

MNPGD) and Mitterrand took the lead. In his memoires he states that he

had started this organisation whilst he was still officially working

for the Vichy Regime. From 27 November 1943 Mitterrand ran the Bureau central de renseignements et d'action. In

December 1943 Mitterrand ordered the execution of Henri Marlin (who

was about to order attacks on the "maquis") by Jacques Paris et Jean

Munier who later hid out with Mitterrand's father. After a second visit

to London in February 1944 Mitterrand took part in the liberation of

Paris. When de Gaulle entered Paris following the Liberation,

he was introduced to various men who were to be part of the provisional

government. Among them was Mitterrand, as secretary general of POWs.

When they came face to face, de Gaulle is said to have muttered: "You

again!" Mitterrand was dismissed 2 weeks later. In October 1944 Mitterrand and Jacques Foccart put together a plan to liberate the POW and concentration camps. This was called operation Viacarage and in April 1945 Mitterrand accompanied General Lewis as the French representative at the liberation of the camps at Kaufering and Dachau on the orders of de Gaulle. By chance Mitterrand discovered his friend and member of his network Robert Antelme suffering

from typhus. Antelme was ordered to remain in the camp to prevent the

spread of disease so Mitterrand arranged for his "escape" and sent him

back to France for treatment. After the war he quickly moved back into politics. At the June 1946 legislative election, he led the list of the Rally of the Republican Lefts (Rassemblement des gauches républicaines or RGR) in the Western suburb of Paris, but he failed to be elected. The RGR was an electoral entity composed of the Radical Party, the centrist Democratic and Socialist Union of the Resistance (Union démocratique et socialiste de la Résistance or UDSR) and several conservative groupings. It opposed the policy of the "Three-parties alliance" (Communists, Socialists and Christian Democrats). In the November 1946 legislative election, he succeeded in winning a seat as deputy in the Nièvre département. To be elected, he had to win a seat at the expense of the French Communist Party (PCF). As leader of the RGR list, he led a very anti-communist campaign.

He then became a member of the UDSR party. In January 1947, he joined

the cabinet as War Veterans Minister. He held various offices in the Fourth Republic as a Deputy and as a Minister (holding eleven different portfolios in total). In May 1948 Mitterrand participated, together with Konrad Adenauer, Winston Churchill, Harold Macmillan, Paul-Henri Spaak, Albert Coppé and Altiero Spinelli, in the Congress of The Hague, which originated the European Movement. As

Overseas Minister (1950 - 1951), he opposed the colonial lobby to propose

a reform programme. He connected with the left when he resigned from

the cabinet after the arrest of Morocco's

sultan (1953). As leader of the progressive wing of the UDSR, he took

the head of the party in 1953, replacing the conservative René Pleven. As Interior Minister in Pierre Mendès-France's cabinet (1954 - 1955), he was faced with the launching of the Algerian War of Independence. He claimed: "Algeria is France." He was also suspected of being the

informer of the Communist Party in the cabinet. This rumour was spread

by the former Paris police prefect, who had been dismissed by him. The

suspicions were dismissed by subsequent investigations. The UDSR joined the Republican Front, a center-left coalition, which won the 1956 legislative election. As Justice Minister (1956 - 1957),

he allowed the expansion of martial law in the Algerian conflict.

Unlike other ministers (including Mendès-France), who criticized the repressive policy in Algeria, he remained in Guy Mollet's cabinet until its end. As Minister of Justice he was an official representative of France during the wedding of Prince of Monaco Rainier III and actress Grace Kelly.

Under the Fourth Republic he was representative of a generation of

young ambitious politicians. He appeared as a possible future Prime

Minister. In 1958, Mitterrand was one of the few to object to the nomination of Charles de Gaulle as head of government, and to de Gaulle's plan for a French Fifth Republic. He justified his opposition by the circumstances of de Gaulle's comeback: the 13 May 1958 quasi-putsch and

military pressure. In September 1958, determinedly opposed to Charles

de Gaulle, Mitterrand made an appeal to vote "no" in the referendum over the Constitution,

which was nevertheless adopted on 4 October 1958. This defeated

coalition of the "No" was composed of the PCF and some left-wing

republican politicians (such as Mendès-France and Mitterrand).

This attitude may have been a factor in Mitterrand's losing his seat in

the 1958 elections,

beginning a long "crossing of the desert" (this term is usually applied

to de Gaulle's decline in influence for a similar period). Indeed, in

the second round of the legislative election, Mitterrand was supported

by the Communists but the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) refused to withdraw its candidate. This division caused the election of the Gaullist candidate. One year later, he was elected to represent Nièvre in the Senate, where he was part of the Group of the Democratic Left. At the same time, he was not admitted to the ranks of the Unified Socialist Party (Parti socialiste unifié,

PSU) which was created by Mendès-France, former internal

opponents of Mollet and reform-minded former members of the Communist

Party. The PSU leaders justified their decision by referring to his

non-resignation from Mollet's cabinet and by his past in Vichy. Also

in that same year, on the Avenue de l'Observatoire in Paris, Mitterrand

claimed to have escaped an assassin's bullet by diving behind a hedge, the Observatory Affair.

The incident brought him a great deal of publicity, initially boosting

his political ambitions. Some of his critics claimed that he had staged

the incident himself, resulting in a backlash against Mitterrand. He

later said he had earlier been warned by right-wing deputy Pesquet that

he was the target of an Algérie française death squad and accused Prime Minister Michel Debré to

be its instigator. Before disappearing, Pesquet claimed that Mitterrand

had set up a fake attempt on his life. Prosecution was initiated

against Mitterrand but was later dropped. In the 1962 election,

he regained his seat in the National Assembly with the support of the

PCF and the SFIO. Practicing left unity in Nièvre, he advocated

the rallying of left-wing forces at the national level, including the

PCF, in order to challenge Gaullist domination. Two years later, he

became the president (chairman) of the General Council of

Nièvre. While the opposition to De Gaulle organized in clubs, he

founded his own group, the Convention of Republican Institutions (Convention des institutions républicaines or CIR). He reinforced his position as a left-wing opponent to Charles de Gaulle in publishing Le Coup d'État permanent (The

permanent coup, 1964), which criticized de Gaulle's personal power, the

weaknesses of Parliament and of the government, the President's

exclusive control of foreign affairs, and defence, etc. In 1965, Mitterrand was the first left-wing politician who saw the presidential election by

universal suffrage as a way to defeat the opposition leadership. Not a

member of any specific political party, his candidacy for presidency

was accepted by all left-wing parties (the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO), French Communist Party (PCF), Radical-Socialist Party (PR) and Unified Socialist Party (PSU)). He ended the cordon sanitaire of the PCF which the party had been subject to since 1947. For the SFIO leader Guy Mollet, Mitterrand's candidacy prevented Gaston Defferre,

his rival in the SFIO, from running for the presidency. Furthemore,

Mitterrand was a lone figure so he did not appear as a danger to the

left-wing parties' staff members. De

Gaulle was expected to win in the first round, but Mitterrand received

31.7% of the vote, denying De Gaulle a first-round victory. Mitterrand

was supported in the second round by the left and other anti-Gaullists:

centrist Jean Monnet, moderate conservative Paul Reynaud and Jean-Louis Tixier-Vignancour, an extreme right-winger, who defended Raoul Salan, one of the four generals who had organized the 1961 Algiers putsch during the Algerian War. Mitterrand

received 44.8% of votes in the second round and de Gaulle, with the

majority, was thus elected for another term, but this defeat was

regarded as honourable, for no one was expected to really defeat de

Gaulle. Mitterrand took the lead of a centre-left alliance: the Federation of the Democratic and Socialist Left (Fédération de la gauche démocrate et socialiste or FGDS). It was composed of the SFIO, the Radicals and several left-wing republican clubs (such the CIR of Mitterrand). In the legislative election of March 1967,

the system where all candidates who failed to pass a 10% threshold in

the first round were eliminated from the second round favoured the

pro-Gaullist majority, which faced a split opposition (PCF, FGDS and

centrists of Jacques Duhamel).

Nevertheless, the parties of the left managed to gain 63 seats more

than previously for a total of 194. The Communists remained the largest

left-wing group with 22.5% of votes. The governing coalition won with

its majority reduced by only one seat (247 seats out of 487). In

Paris, the Left (FGDS, PSU, PCF) managed to win more votes in the first

round than the two governing parties (46% against 42.6%) while the Democratic Centre of Duhamel got 7% of votes. But with 38% of votes, de Gaulle's Union for the Fifth Republic remained the leading French party. During

the May 1968 governmental crisis, Mitterrand held a press conference to

announce his candidacy if a new presidential election was held. But

after the Gaullist demonstration on the Champs-Elysées, de Gaulle dissolved the Assembly and called for a legislative election instead. In this election, the right wing won its largest majority since the Bloc National in 1919. Mitterrand

was accused of being responsible for this huge legislative defeat and

the FGDS split. In 1969, Mitterrand could not run for the Presidency: Guy Mollet refused

to give him the support of the SFIO. The left wing was eliminated in

the first round, with the Socialist candidate Gaston Defferre winning a

humiliating 5.1 percent of the total vote. Georges Pompidou faced the centrist Alain Poher in the second round. After the FGDS's implosion, Mitterrand turned to the Socialist Party (Parti socialiste or "PS"). In June 1971, at the time of the Epinay Congress, the CIR joined the "PS", which had replaced the SFIO in 1969. The executive of the "PS" was then dominated by Guy Mollet's

supporters. They proposed an "ideological dialogue" with the

Communists. For Mitterrand, an electoral alliance was necessary to rise

to power. With this project, Mitterrand obtained the support of all the

internal opponents to Mollet's faction and he was elected as the first

secretary of the "PS". In June 1972, Mitterrand signed the Common Programme of Government with the Communist Georges Marchais and the Left Radical Robert Fabre. With this programme, he led the 1973 legislative campaign of the "Union of the Left". At the 1974 presidential election, Mitterrand received 43.2% of the vote in the first round, as the common candidate of the left wing. He next faced Valéry Giscard d'Estaing in

the second round. During the national TV debate, Giscard d'Estaing

criticized him as being "a man of the past", due to his long political

career. Mitterrand was defeated in a near tie by Giscard d'Estaing,

Mitterrand receiving (49.19%) and Giscard (50.81%). In 1977, the Communist and Socialist parties failed to update the Common Programme, then lost the 1978 legislative election. Whilst the Socialists took the leading role on the left, in obtaining more votes than the Communists for the first time since 1936, the leadership of Mitterrand was challenged by an internal opposition led by Michel Rocard who

criticized the programme of the PS as being "archaic" and

"unrealistic". The polls indicated Rocard was more popular than

Mitterrand. Nevertheless, Mitterrand won the vote at the Party's Metz Congress (1979) and Rocard renounced his candidacy for the 1981 presidential election. For

his third candidacy for presidency, Mitterrand was not supported by the

PCF but only by the PS. He projected a reassuring image with the slogan

"the quiet force". He campaigned for "another politics", based on the 110 Propositions for France Socialist

program, and denounced the performance of the incumbent president.

Furthemore, he benefited from the conflict in the right-wing majority.

He obtained 25.85% of votes in the first round (against 15% for the PCF

candidate Georges Marchais) then defeated President Giscard d'Estaing in the second round, with 51.76%. He became the first left-wing politician elected President of France by universal suffrage. In the presidential election of 1981,

Mitterrand became the first socialist President of the Fifth Republic,

and his government became the first left-wing government in 23 years.

He named Pierre Mauroy as Prime Minister and organised a new legislative election.

The Socialists obtained an absolute parliamentary majority, and four

Communists joined the cabinet. The beginning of his first term was

marked by a left-wing economic policy based on the 110 Propositions for France and the 1972 Common Programme between the Socialist Party, the Communist Party and the Left Radical Party. This included several nationalizations, a 10% increase of the minimum wage (SMIC), a 39 hour work week, 5 weeks holiday per year, the creation of the solidarity tax on wealth,

an increase in social benefits, and the extension of workers' rights to

consultation and information about their employers (through the Auroux Act). The objective was to boost economic demand and thus economic activity (Keynesianism). However, unemployment continued to grow and three devaluations of the franc were decided upon. This policy more or less came to an end with the March 1983 liberal turn. Priority was given to the struggle against inflation in order to remain competitive in the European Monetary System. With respect to social and cultural policies, Mitterrand abrogated the death penalty as soon as he took office (via the Badinter Act), as well as the "anti-casseurs Act" which instituted however collective responsibility for acts of violence during demonstrations. He also dissolved the Cour de sûreté, a special high court and enacted a massive regularization of illegal immigrants. Mitterrand passed the first decentralizations laws (Defferre Act) and liberalized the media, created the CSA media regulation agency, and authorized pirate radio and the first private TV (Canal+), giving rise to the private broadcasting sector. In 1983, Mitterrand became an honorary citizen of Belgrade. The Left lost the 1983 municipal elections and the 1984 European Parliament election. At the same time, the Savary Bill to

limit the financing of private schools by local communities, caused a

political crisis. It was abandoned and Mauroy resigned in July 1984. Laurent Fabius succeeded him. The Communists left the cabinet. Before the 1986 legislative campaign, proportional representation was instituted in accordance with the 110 Propositions. It did not prevent, however, the victory of the Rally for the Republic/Union for French Democracy (RPR/UDF) coalition. Mitterrand thus named the RPR leader Jacques Chirac as

Prime Minister. This period of government, with a President and a Prime

Minister who came from two opposite coalitions, was the first time that

such a combination had occurred under the Fifth Republic, and came to

be known as "Cohabitation". Chirac

handled mostly domestic policy while Mitterrand concentrated on his

"reserved domain": foreign affairs and defence. However, several

conflicts opposed the two heads of the executive power. In this,

Mitterrand refused to sign decrees of liberalization, obligating Chirac

to pass by the parliamentary way. He supported covertly the social

movements, notably the student revolt against the university reform (Devaquet Bill). Benefiting from the difficulties of Chirac's cabinet, his popularity increased. The polls being positive for him, he announced his candidacy in the 1988 presidential election.

He proposed a moderate programme (promising "neither nationalisations

nor liberalisation") and advocated a "united France". He obtained 34%

of votes in the first round, then was opposed to Chirac in the second,

and was re-elected with 54% of votes. Mitterrand was the first

President to be elected twice by universal suffrage. After his re-election, he named Michel Rocard as

Prime Minister, in spite of their poor relations. Rocard led the

moderate wing of the PS and he was the most popular of the Socialist

politicians. Mitterrand decided to organize a new legislative election.

The PS obtained a relative parliamentary majority. Four centre-right

politicians joined the cabinet. The second term was marked by the Matignon Agreements concerning New Caledonia, the creation of the Insertion Minimum Revenue (RMI),

which ensured a minimum level of income to those deprived of any other

form of income, the restoring of the solidarity tax on wealth, which

had been abolished by Chirac's cabinet, the institution of the Generalized social tax, the reform of the Common Agricultural Policy, the 1990 Gayssot Act on hate speech and Holocaust denial, the Arpaillange Act on the financing of political parties, the reform of the penal code and the Evin Act on smoking in public places. Several large architectural works were pursued, with the building of the Louvre Pyramid, the Channel Tunnel, the Grande Arche at La Défense, the Bastille Opera, the Finance Ministry in Bercy, the National Library of France. But the second term was also marked by the rivalries in the PS and the split of the Mitterrandist group (at the Rennes Congress, where supporters of Laurent Fabius and Lionel Jospin clashed bitterly for control of the party), the scandals about financing of the party, the contaminated blood scandal which implicated Laurent Fabius and former ministers Georgina Dufoix and Emond Hervé, and the Elysée wiretaps affairs. Disappointed with Rocard's failure to enact the Socialists' programme, Mitterrand dismissed Rocard in 1991 and appointed Edith Cresson to

replace him. She was the first woman to become Prime Minister in

France, but was forced to resign after the disaster of the 1992

regional elections. Her successor Pierre Bérégovoy promised to fight unemployment and corruption but he could not prevent the catastrophic defeat of the left in the 1993 legislative election. He committed suicide on 1 May 1993. On 16 February 1993, President Mitterrand inaugurated in Fréjus a Memorial to the Wars in Indochina. Mitterrand named the former RPR Finance Minister Edouard Balladur as

Prime Minister. The second "cohabitation" was less contentious than the

first, because the two men knew they were not rivals for the next

presidential election. Mitterrand was weakened by his cancer, the

scandal about his past in Vichy, and the suicide of his friend François de Grossouvre. His second and last term ended after 1995 presidential election in May 1995 with the election of Jacques Chirac. Mitterrand died of prostate cancer on 8 January 1996 at the age of 79. Mitterrand

supported closer European collaboration and the preservation of

France's special relationship with its former colonies, which he feared

were falling under "Anglo-Saxon influence." His drive to preserve French power in Africa led to controversies concerning Paris' role during the Rwandan Genocide. Despite Mitterrand's left-wing affiliations, the 1980s saw France becoming more distant from the USSR.

When Mitterrand visited the USSR in November 1988, the Soviet media

claimed to be 'leaving aside the virtually wasted decade and the loss

of the Soviet-French 'special relationship' of the Gaullist era'.

Nevertheless, Mitterrand was worried by the rapidity of the Soviet

bloc's collapse. He was opposed to German Reunification,

even thinking of a military alliance with Russia to stop it,

“camouflaged as a joint use of armies to fight natural disasters”. He made a controversial visit to East Germany after the fall of Berlin Wall. He was opposed to the swift recognition of Croatia and Slovenia, which he thought would lead to the violent implosion of Yugoslavia. France participated in the Gulf War (1990-1991) with the U.N. coalition.

His major achievements came internationally, especially in the European Economic Community.

He supported the enlargement of the Community to include Spain and

Portugal (which both joined in January 1986). In February 1986 he

helped the Single European Act come into effect. He worked well with Helmut Kohl and improved Franco-German relations significantly. Together they fathered the Maastricht Treaty, which was signed on 7 February 1992. It was ratified by referendum, approved by just over 51% of the voters. Responding to a democratic movement in Africa after the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall, he made his famous La Baule speech in June 1990 which tied development aid to democratic efforts from former French colonies, and during which he opposed the devaluation of the CFA Franc.

Seeing an "East wind" blowing in the former Soviet Union and Eastern

Europe, he stated that a "Southern wind" was also blowing in Africa,

and that state leaders had to respond to the populations' wishes and

aspirations by a "democratic opening", which included a representative system, free elections, multipartyism, freedom of the press, an independent judiciary, and abolition of censorship. Recalling that France was the country making the most important effort concerning development aid, he announced that Least Developed Countries (LDCs) would receive only donations (in order to stop the massive increase of the Third World debt during the 1980s, and limited the interest rate to 5% for intermediary countries (that is, Côte d'Ivoire, Congo, Cameroon and Gabon). In a clear allusion to the shady system known as Françafrique, he also criticized interventionism in sovereign matters, which was according to him only another form of "colonialism." However, according to Mitterrand, this did not induce lesser concern of Paris for its former colonies,

Mitterrand hence continuing with the African policy of de Gaulle

inaugurated in 1960, which followed the relative failure of the 1958

creation of the French Community.

All in all, Mitterrand's La Baule speech, which marked a relative

turning in France's policy concerning its former colonies, has been

compared with the 1956 loi-cadre Defferre which was responding to anti-colonialist feelings. However, African heads of state themselves reacted at most with indifference. Omar Bongo, President of Gabon, declared that he rather had "events counsel him;" Abdou Diouf,

President of Senegal, said that according to him, the best solution was

a "strong government" and a "good faith opposition;" the President of

Chad, Hissène Habré (nicknamed the "African Pinochet")

claimed that it was contradictory to demand that African states should

simultaneously carry on a "democratic policy" and "social and economic

policies which limited their sovereignty", (in a clear allusion to the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank's "structural adjustment programs." Hassan II,

the former king of Morocco, said for his part that "Africa was too open

to the world to remain indifferent to what was happening around it",

but that Western countries should "help young democracies open out,

without putting a knife under their throat, without a brutal transition

to multipartyism." All

in all, the La Baule speech has been said to be on one hand "one of the

foundations of political renewal in Africa French speaking area", and

on the other hand "cooperation with France", this despite "incoherence

and inconsistency, like any public policy"

Controversy surrounding the discovery of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) was intense after American researcher Robert Gallo and French scientist Luc Montagnier both claimed to have discovered it. The two scientists had given the new virus different names. The controversy was eventually settled by an agreement (helped along by the mediation of Dr Jonas Salk) between President Ronald Reagan and Mitterrand which gave equal credit to both men and their teams.

On 2 February 1993, in his capacity as co-prince of Andorra, Mitterrand and Joan Martí Alanis, who was Bishop of Urgell and therefore Andorra's other co-prince, signed Andorra's new constitution, which was later approved by referendum in the principality.

Following his death, a controversy erupted when his former physician, Dr Claude Gubler, wrote a book called Le Grand Secret ("The Great Secret") explaining that Mitterrand had had false health reports

published since November 1981, hiding his cancer. Mitterrand's family

then prosecuted Gubler and his publisher for violating medical secrecy. Mitterrand

came under fire in 1992 when it was revealed that he had arranged for

the laying of a wreath of flowers on the grave of Philippe Pétain each Armistice Day since 1987. The placing of such a wreath was not without precedent: Presidents Charles de Gaulle and Valéry Giscard d'Estaing had wreaths placed on Pétain's grave to commemorate the 50th and 60th anniversaries of the end of World War I. Pétain had been the leader of French forces at the dramatic Battle of Verdun in World War I, for which he was revered by his contemporaries. Later, however, he became leader of Vichy France after the French defeat to Germany in World War II, collaborating with Nazi Germany and putting anti-semitic measures into place. Similarly, President Georges Pompidou had a wreath placed in 1973 when Pétain's remains were returned to the Ile d'Yeu after

being stolen. But Mitterrand's annual tributes marked a departure from

those of his predecessors, and offended sensibilities at a time when

France was re-examining its role in the Holocaust.

The Urba consultancy was established in 1971 by the Socialist Party to advise Socialist-led communes on infrastructure projects and public works. The Urba affair became public in 1989 when two police officers investigating the Marseille regional

office of Urba discovered detailed minutes of the organisation's

contracts and division of proceeds between the party and elected

officials. Although the minutes proved a direct link between Urba and

graft activity, an edict from the office of Mitterrand, himself listed

as a recipient, prevented further investigation. The Mitterrand

election campaign of 1988 was directed by Henri Nallet, who then became Justice Minister and

therefore in charge of the investigation at national level. In 1990

Mitterrand declared an amnesty for those under investigation, thus

ending the affair. Socialist Party treasurer Henri Emmanuelli was tried in 1997 for corruption offences, for which he received a two year suspended sentence.

Mitterrand had numerous extramarital affairs, one of which was with mistress Anne Pingeot; they had a daughter, Mazarine.

Mitterrand sought secrecy on that issue, which lasted until November

1994, when Mitterrand's failing health and impending retirement meant

he could no longer count on the fear and respect he had once engendered

among French journalists. Also, Mazarine, a college student, had

reached an age where her identity could no longer be protected as a

minor. From

1982 to 1986, Mitterrand established an "anti-terror cell" installed as

a service of the President of the Republic. This was a fairly unusual

set-up, since such law enforcement missions against terrorism are

normally left to the National Police and Gendarmerie, run under the cabinet and the Prime Minister, and under the supervision

of the judiciary. The cell was largely made from members of these

services, but it bypassed the normal line of command and safeguards.

3000 conversations concerning 150 people (7 for reasons judged to be

contestable by the ensuing court process) were recorded between January

1983 and March 1986 by this anti terrorist cell at the Elysée

Palace. Most markedly, it appears that the cell, under illegal presidential orders, obtained wiretaps on journalists,

politicians and other personalities who may have been an impediment for

Mitterrand's personal life. The illegal wiretapping was revealed in

1993 by Libération; the case against members of the cell went to trial in November 2004. It took 20 years for the 'affaire' to come before the courts because the instructing judge Jean-Paul Vallat was at first thwarted by the 'affaire' being classed a defence secret but in December 1999 la Commission consultative du secret de la défense nationale declassified

part of the files concerned. The Judge finished his investigation in

2000, but it still took another four years before coming to court on 15

November 2004 before the 16th chamber of the tribunal correctionnel de

Paris. 12 people were charged with "atteinte à la vie

privée" (breach of privacy) and one with selling computer files.

7 were given suspended sentences and fines and 4 were found not guilty. The 'affaire' finally ended before the Tribunal correctionnel de

Paris with the court's judgement on 9 November 2005. 7 members of the

President's anti-terrorist unit were condemned and Mitterrand was

designated as the "inspirator and essentially the controller of the

operation." The

courts judgement revealed that Mitterrand was motivated by keeping

elements of his private life secret from the general public, such as

the existence of his illegitimate daughter Mazarine Pingeot (which the writer Jean-Edern Hallier,

was threatening to reveal), his cancer of the prostate which was

diagnosed in 1981 and the elements of his past in the Vichy

Régime which were not already public knowledge. The court judged

that certain people were tapped for "obscure" reasons, such as Carole Bouquet's companion, a lawyer with family in the Middle East, Edwy Plenel, a journalist for le Monde who covered the Rainbow Warrior story

and the lawyer Antoine Comte. The court declared " Les faits avaient

été commis sur ordre soit du président de la

République, soit des ministres de la Défense successifs

qui ont mis à la disposition de (Christian Prouteau)

tous les moyens de l'État afin de les exécuter (these

actions were committed following orders from the French President or

his various Defence Ministers who gave Christian Prouteau full

access to the state machinery so he could execute the orders)" The

court stated that Mitterrand was the principal instigator of the wire

taps (l'inspirateur et le décideur de l'essentiel) and that he

had ordered some of the taps and turned a blind eye to others and that

none of the 3000 wiretaps carried out by the cell were legally obtained. On 13 March 2007 the Court of Appeal in Paris awarded 1€ damages to the actress Carole Bouquet and 5000€ to Lieutenant-Colonel Jean-Michel Beau for breach of privacy. The case was taken to the European Court of Human Rights,

which gave judgement on 7 June 2007 that the rights of free expression

of the journalists involved in the case were not respected. In 2008 the

French state was ordered by the courts to give Jean-Edern Hallier's

family compensation.

Paris assisted Rwanda's president Juvénal Habyarimana, who was assassinated on 6 April 1994 while travelling in a Dassault Falcon 50 given

to him as a personal gift of Mitterrand. Through the offices of the

'Cellule Africaine', a Presidential office headed by Mitterrand's son, Jean-Christophe,

he provided the Hutu regime with financial and military support in the

early 1990s. With French assistance, the Rwandan army grew from a force

of 9,000 men in October 1990 to 28,000 in 1991. France also provided

training staff, experts and massive quantities of weaponry and

facilitated arms contracts with Egypt and South Africa. It also

financed, armed and trained Habyrimana's Presidential Guard. French

troops were deployed under Opération Turquoise, a military operation carried out under a United Nations (UN) mandate. The operation is currently the object of political and historical debate. The Rainbow Warrior, a Greenpeace vessel, was in New Zealand preparing to protest against French nuclear testing in the South Pacific when an explosion sank the ship. Photographer Fernando Pereira drowned

in the ensuing chaos as he tried to retrieve his equipment. The New

Zealand government called the bombing the first terrorist attack in the

country. In mid-1985, Defense Minister Charles Hernu was forced to resign after the discovery of the French implication in the attack against the Rainbow Warrior. On the twentieth anniversary of the sinking it was revealed that Mitterrand had personally authorised the bombing which caused the casualty. Admiral Pierre Lacoste, the former head of the DGSE,

made a statement saying Pereira's death weighed heavily on his

conscience. Also on that anniversary, Television New Zealand (TVNZ)

sought to access a video recording made at the preliminary hearing where two French agents pleaded guilty, a battle they won in 2006.