<Back to Index>

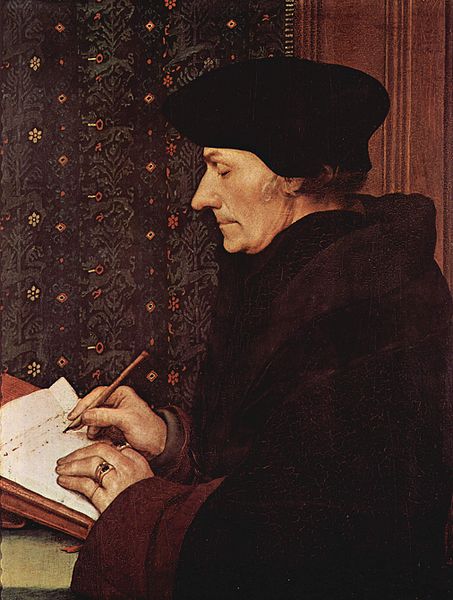

- Philosopher Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus, 1466/69

- Painter Giovanni Antonio Canal (Canaletto), 1697

- Vice-Admiral Peter Jansen Wessel (Tordenskjold), 317

PAGE SPONSOR

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (October 28, 1466/1469 – July 12, 1536), sometimes known as Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam, was a Dutch Renaissance humanist and a Catholic priest and theologian. His scholarly name Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus comprises the following three elements: the Latin noun desiderium ("longing" or "desire"; the name being a genuine Late Latin name); the Greek adjective ἐράσμιος (erásmios) meaning "desired", and, in the form Erasmus, also the name of a St. Erasmus of Formiae; and the Latinized adjectival form for the city of Rotterdam (Roterodamus = "of Rotterdam").

Erasmus was a classical scholar who wrote in a "pure" Latin style and enjoyed the sobriquet "Prince of the Humanists." He has been called "the crowning glory of the Christian humanists." Using humanist techniques for working on texts, he prepared important new Latin and Greek editions of the New Testament. These raised questions that would be influential in the Protestant Reformation and Catholic Counter-Reformation. He also wrote The Praise of Folly, Handbook of a Christian Knight, On Civility in Children, Copia: Foundations of the Abundant Style, Julius Exclusus, and many other works. Erasmus lived through the Reformation period and he consistently criticized some contemporary popular Christian beliefs. In relation to clerical abuses in the Church, Erasmus remained committed to reforming the Church from within. He also held to Catholic doctrines such as that of free will, which some Protestant Reformers rejected in favor of the doctrine of predestination. His middle road approach disappointed and even angered many Protestants, such as Martin Luther,

as well as conservative Catholics. He died in Basel in 1536 and was

buried in the formerly Catholic cathedral there, recently converted to

a Reformed church. Desiderius Erasmus was born Gerrit Gerritszoon (Gerard Gerard's son) or Herasmus Gerritszoon in Gouda, 20 km from Rotterdam, on July 12, in 1466.

The exact year of his birth is debated but some evidence confirming

1466 can be found in Erasmus' own words. Of twenty-three statements

Erasmus made about his age, all but one of the first fifteen indicate

1466. It is possible he was christened "Erasmus" after the saint of that name. Although

associated closely with Rotterdam, he lived there for only four years,

never to return. Information on his family and early life comes mainly

from vague references in his writings. His parents almost certainly were not legally married. His father, named Roger Gerard, later became a priest and afterwards curate in Gouda. Little is known of his mother other than that her name was Margaret and she was the daughter of a physician. Although he was born out of wedlock, Erasmus was cared for by his parents until their early deaths from the plague in

1483. He was then given the very best education available to a young

man of his day, in a series of monastic or semi-monastic schools, most

notably a school run by the Brethren of the Common Life (inspired by Geert Groote) where he gleaned the importance of a personal relationship with God but eschewed the harsh rules and strict methods of the religious brothers and educators. While at the Augustinian monastery Steyn near

Gouda around 1487, young Erasmus wrote a series of passionate letters

to a fellow monk, Servatius Rogerus, whom he called "half my soul",

writing, "I have wooed you both unhappily and relentlessly"; Whether this is evidence for homosexual desire

or simply male-to-male friendship is unclear; nevertheless this

correspondence contrasts sharply with the generally detached and much

more restrained attitude he showed in his later life. Of similar

interest was the sudden dismissal by the guardian of Thomas Grey, a

student Erasmus tutored in Paris which could be taken as grounds of an

illicit affair.

However, no personal denunciation was made of Erasmus during his

lifetime, he took pains to condemn sodomy in his works, and instead

praised sexual desire in the context of marriage between men and women.

In 1492, poverty forced Erasmus into the monastery. He was ordained to the Catholic priesthood and took vows as an Augustinian canon at

Steyn at about the age of 25, but he never seemed to have actively

worked as a priest for a longer time, and certain tenets of monasticism were

among the chief objects of his attack in his lifelong assault upon

Church excesses. Soon after his priestly ordination, he got his chance

to leave the monastery when offered the post of secretary to the Bishop of Cambray, Henry of Bergen, on account of his great skill in Latin and his reputation as a man of letters. In order to allow him to accept that post, he was given a temporary dispensation from his monastic vows on the grounds of poor health and love of Humanistic studies, though he remained a "secular priest". Pope Leo X later made the dispensation permanent, a considerable privilege at the time. In 1495, with the bishop's consent and stipend, he went on to study at the University of Paris, in the Collège de Montaigu, a centre of reforming zeal, under the direction of the ascetic Jan Standonck, of whose rigours Erasmus complained. The University was then the chief seat of Scholastic learning, but already coming under the influence of Renaissance humanism. For instance, Erasmus became an intimate friend of an Italian Humanist Publio Fausto Andrelini, poet and "professor of humanity" in Paris. The chief centers of Erasmus's activity were Paris, Leuven (Louvain in Brabant), England,

and Basel; yet he never belonged firmly in any one of these places. His

time in England was fruitful in the making of lifelong friendships with

the leaders of English thought in the stirring days of King Henry VIII: John Colet, Thomas More, John Fisher, Thomas Linacre and William Grocyn. At the University of Cambridge, he was the Lady Margaret's Professor of Divinity and had the option of spending the rest of his life as an English professor. He stayed at Queens' College, Cambridge, and may have been an alumnus. In

1499, while in England, Erasmus was particularly impressed by the Bible

teaching of John Colet who pursued a style more akin to the church fathers than the scholastics. This prompted him, upon his return from England, to master the Greek

language, which would enable him to study theology on a more profound

level and to prepare a new edition of Jerome's Bible translation. On one occasion he wrote Colet: "I

cannot tell you, dear Colet, how I hurry on, with all sails set, to

holy literature. How I dislike everything that keeps me back, or

retards me." Despite

a chronic shortage of money, he succeeded in learning Greek by an

intensive, day-and-night study of three years, continuously begging his

friends to send him books and money for teachers in his letters. Discovery in 1506 of Lorenzo Valla's New Testament Notes encouraged Erasmus to continue the study of the New Testament. Erasmus

preferred to live the life of an independent scholar and made a

conscious effort to avoid any actions or formal ties that might inhibit

his freedom of intellect and literary expression. Throughout his life,

he was offered many positions of honor and profit throughout the

academic world but declined them all, preferring the uncertain but

sufficient rewards of independent literary activity. From 1506 to 1509,

he was in Italy: in 1506 he graduated at the Turin University, and he spent part of the time at the publishing house of Aldus Manutius in Venice. According to his letters, he was associated with the Venetian natural philosopher, Giulio Camillo, but, apart from this, he had a less active association with Italian scholars than might have been expected. His

residence at Leuven, where he lectured at the Catholic University,

exposed Erasmus to much criticism from those ascetics, academicians and

clerics hostile to the principles of literary and religious reform and

the loose norms of the Renaissance adherents to which he was devoting

his life. In 1517, he supported the foundation at the University, by

his friend Jeroen van Busleyden, of the Collegium Trilingue for the study of Hebrew, Latin, and Greek - after the model of the College of the Three Languages at the University of Alcalá.

However, feeling that this lack of sympathy was actually a form of

mental persecution, he sought refuge in Basel, where under the shelter

of Swiss hospitality he could express himself freely and where he was

surrounded by devoted friends. Here he was associated for many years

with the great publisher Johann Froben, and to him came the multitude of his admirers from all quarters of Europe. Only when he had mastered Latin did he begin to express himself on major contemporary themes in literature and religion.

He felt called upon to use his learning in a purification of the

doctrine by returning to the historic documents and original languages

of sacred Scripture. He tried to free the methods of scholarship from

the rigidity and formalism of medieval traditions, but he was not

satisfied with this. His revolt against certain forms of Christian monasticism and

scholasticism was not based on doubts about the truth of doctrine, nor

from hostility to the organization of the Church itself, nor from

rejection of celibacy or

monastical lifestyles. He saw himself as a preacher of righteousness by

an appeal to reason, applied frankly and without fear of the magisterium.

He always intended to remain faithful to Catholic doctrine, and

therefore was convinced he could criticize frankly and virtually

everyone. Erasmus

held himself aloof from entangling obligations, yet

he was the center of the literary movement of his time. He corresponded

with more than five hundred men in the worlds of politics and of

thought.

The first New Testament printed in Greek was part of the Complutensian Polyglot.

This portion was printed in 1514, but publication was delayed until

1522 by waiting for the Old Testament portion, and the sanction of Pope Leo X. Erasmus

had been working for years on two projects: a collation of Greek texts

and a fresh Latin New Testament. In 1512, he began his work on this

Latin New Testament. He collected all the Vulgate manuscripts he could

find to create a critical edition. Then he polished the Latin. He

declared, "It is only fair that Paul should address the Romans in

somewhat better Latin." In

the earlier phases of the project, he never mentioned a Greek text: "My

mind is so excited at the thought of emending Jerome’s text, with

notes, that I seem to myself inspired by some god. I have already

almost finished emending him by collating a large number of ancient

manuscripts, and this I am doing at enormous personal expense." While

his intentions for publishing a fresh Latin translation are clear, it

is less clear why he included the Greek text. Though some speculate

that he intended to produce a critical Greek text or that he wanted to

beat the Complutensian Polyglot into print, there is no evidence to

support this. He wrote, "There remains the New Testament translated by

me, with the Greek facing, and notes on it by me." He

further demonstrated the reason for the inclusion of the Greek text

when defending his work: "But one thing the facts cry out, and it can

be clear, as they say, even to a blind man, that often through the

translator’s clumsiness or inattention the Greek has been wrongly

rendered; often the true and genuine reading has been corrupted by

ignorant scribes, which we see happen every day, or altered by scribes

who are half-taught and half-asleep." So

he included the Greek text to permit qualified readers to verify the

quality of his Latin version. But by first calling the final product

"Novum Instrumentum omne" ("All of the New Teaching") and later "Novum

Testamentum omne" ("All of the New Testament") he also indicated

clearly that he considered a consistently parallelized version of both

the Greek and the Latin texts as the essential dual core of the

church's New Testament tradition. In a way it is legitimate to say that

Erasmus "synchronized" or "unified" the Greek and the Latin traditions

of the New Testament by producing an updated (he would say: "purified")

version of either simultaneously. Both being part of canonical

tradition, he clearly found it necessary to ensure that both were

actually presenting the same content. In modern terminology, he made

the two traditions "compatible". This is clearly evidenced by the fact

that his Greek text is not just the basis for his Latin translation,

but also the other way round: there are numerous instances where he

edits the Greek text to reflect his Latin version. For instance, since

the last six verses of Revelation were

missing from his Greek manuscript, Erasmus translated the Vulgate's

text back into Greek. Erasmus also translated the Latin text into Greek

wherever he found that the Greek text and the accompanying commentaries

were mixed up, or where he simply preferred the Vulgate’s reading to

the Greek text. Erasmus's hurried effort (Erasmus said it was "rushed into print rather than edited") was published by his friend Johann Froben of Basel in 1516 and thence became the first published Greek New Testament, the Novum Instrumentum omne, diligenter ab Erasmo Rot. Recognitum et Emendatum.

Erasmus used several Greek manuscript sources because he did not have

access to a single complete manuscript. Most of the manuscripts were,

however, late Greek manuscripts of the Byzantine textual family and

Erasmus used the oldest manuscript the least because "he was afraid of

its supposedly erratic text." He also ignored much older and better manuscripts that were at his disposal. In the 2nd (1519) edition the more familiar term Testamentum was used instead of Instrumentum.

This edition was used by Martin Luther in making his German translation

of Bible for his own religious movement. Together, the first and second

editions sold 3,300 copies. Only 600 copies of the Complutensian

Polyglot were even printed. The 1st- and 2nd-edition texts did not

include the passage (1 John 5:7–8) that has become known as the Comma Johanneum.

Erasmus had been unable to find those verses in any Greek manuscript,

but one was supplied to him during production of the 3rd edition. That

manuscript is now thought to be a 1520 creation from the Latin Vulgate,

which likely got the verses from a fifth-century marginal gloss in a

Latin copy of I John. The Roman Catholic Church decreed that the Comma Johanneum was open to dispute (June 2, 1927), and it is rarely included in modern scholarly translations. The 3rd edition of 1522 was probably used by Tyndale for

the first English New Testament (Worms, 1526) and was the basis for the

1550 Robert Stephanus edition used by the translators of the Geneva Bible and King James Version of

the English Bible. Erasmus published a definitive 4th edition in 1527

containing parallel columns of Greek, Latin Vulgate and Erasmus's Latin

texts. He used the now available Polyglot Bible to improve this

version. In this edition Erasmus also supplied the Greek text of the

last six verses of Revelation (which he had translated from Latin back into Greek in his first edition) from Cardinal Ximenez's Biblia Complutensis.

In 1535 Erasmus published the 5th (and final) edition which dropped the

Latin Vulgate column but was otherwise similar to the 4th edition.

Subsequent versions of Erasmus's Greek New Testament became known as the Textus Receptus. Erasmus

dedicated his work to Pope Leo X as a patron of learning and regarded

this work as his chief service to the cause of Christianity.

Immediately afterward, he began the publication of his Paraphrases of the New Testament,

a popular presentation of the contents of the several books. These,

like all of his writings, were published in Latin but were quickly

translated into other languages, with his encouragement.

Martin

Luther's movement began in the year following the publication of the

New Testament and tested Erasmus's character. The issue between

European society and the Roman Church had become so clear that few

could escape the summons to join the debate. Erasmus, at the height of

his literary fame, was inevitably called upon to take sides, but

partisanship was foreign to his nature and his habits. In all his

criticism of clerical follies and abuses, he had always protested that

he was not attacking church institutions themselves and had no enmity

toward churchmen. The world had laughed at his satire,

but few had interfered with his activities. He believed that his work

so far had commended itself to the best minds and also to the dominant

powers in the religious world. Initially

Erasmus was sympathetic with the main points in Martin Luther's

criticism of the Catholic Church, describing him as "a mighty trumpet

of gospel truth" and admitting that, "It is clear that many of the

reforms for which Luther calls are urgently needed.” He

had great respect for Martin Luther, and Luther always spoke with

admiration of Erasmus's superior learning. Luther hoped for his

cooperation in a work which seemed only the natural outcome of his own.

In their early correspondence, Luther expressed boundless admiration

for all Erasmus had done in the cause of a sound and reasonable

Christianity and urged him to join the Lutheran party. Erasmus declined

to commit himself, arguing that to do so would endanger his position as

a leader in the movement for pure scholarship which he regarded as his

purpose in life. Only as an independent scholar could he hope to

influence the reform of religion. When Erasmus hesitated to support

him, the straightforward Luther felt angered that Erasmus was avoiding

the responsibility due either to cowardice or a lack of purpose. Erasmus, however, dreaded any change in doctrine and

believed that there was room within existing formulas for the kind of

reform he valued most. Also, it is said that Erasmus chose to remain a

Roman Catholic because of a lecture he heard from Savonarola, the Dominican friar who ruled Florence for

a time. Though he remained firmly neutral, each side accused him of

siding with the other, perhaps because of his neutrality. It was not

for lack of fidelity with either side but a desire for fidelity with

them both: "I

detest dissension because it goes both against the teachings of Christ

and against a secret inclination of nature. I doubt that either side in

the dispute can be suppressed without grave loss." In his Catechism (entitled Explanation of the Apostles' Creed) (1533), Erasmus took stand against Luther's teaching by asserting the unwritten Sacred Tradition as just as valid a source of revelation as the Bible, by enumerating the Deuterocanonical books in the canon of the Bible and by acknowledging seven sacraments. He called "blasphemers" anyone who questioned the perpetual virginity of Mary and those who defended the need to occasionally restrict the laity from access to the Bible. In a letter to Nikolaus von Amsdorf, Luther objected to Erasmus’ Catechism and called Erasmus a "viper,", "liar," and "the very mouth and organ of Satan." As

the popular response to Luther gathered momentum, the social disorders,

which Erasmus dreaded and Luther disassociated himself from, began to

appear, including the Peasants' War, the Anabaptist disturbances in Germany and in the Low Countries, iconoclasm and the radicalization of

peasants across Europe. If these were the outcomes of reform, he was

thankful that he had kept out of it. Yet he was ever more bitterly

accused of having started the whole "tragedy" (as the Roman Catholics

dubbed Protestantism). When

the city of Basel was definitely and officially "reformed" in 1529,

Erasmus gave up his residence there and settled in the imperial town of Freiburg im Breisgau. A test of the Reformation was the doctrine of the sacraments, and the crux of this question was the observance of the Eucharist. In 1530, Erasmus published a new edition of the orthodox treatise of Algerus against the heretic Berengar of Tours in

the eleventh century. He added a dedication, affirming his belief in

the reality of the Body of Christ after consecration in the Eucharist,

commonly referred to as transsubstantiation. The anti-sacramentarians, headed by Œcolampadius of

Basel, were, as Erasmus says, quoting him as holding views similar to

their own in order to try to claim him for their schismatic and

"erroneous" movement. Erasmus died of a sudden attack of dysentery in 1536 in Basel and was buried there in the cathedral. His last words, as recorded by his friend Beatus Rhenanus, were "lieve God", Dutch for Dear God.