<Back to Index>

- Astronomer William Cranch Bond, 1789

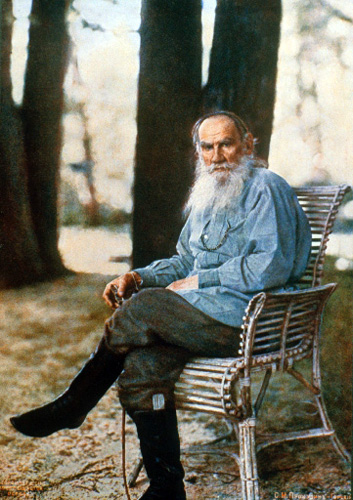

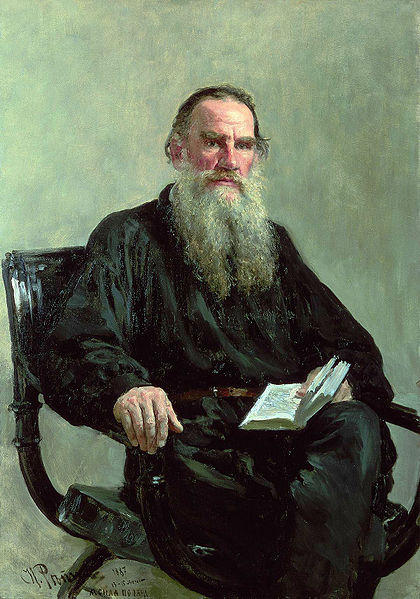

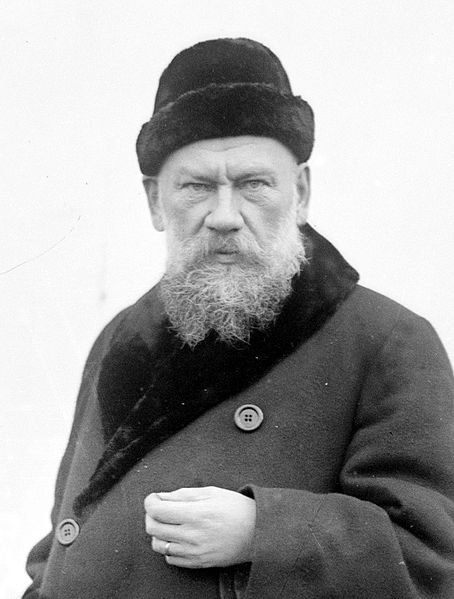

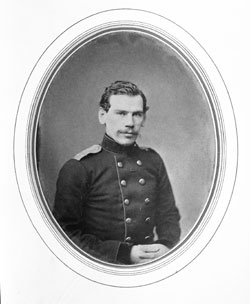

- Novelist Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, 1828

- 1st Chief Minister of the French King Armand Jean du Plessis, Cardinal-Duc de Richelieu, 1585

Leo Tolstoy, or Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy (Russian: Лев Никола́евич Толсто́й; September 9 [O.S.August 28] 1828 – November 20 [O.S. November 7] 1910), was a Russian writer widely regarded as among the greatest of novelists. His masterpieces War and Peace and Anna Karenina represent in their scope, breadth and vivid depiction of 19th-century Russian life and attitudes, the peak of realist fiction.

Tolstoy's further talents as essayist, dramatist, and educational reformer made him the most influential member of the aristocratic Tolstoy family. His literal interpretation of the ethical teachings of Jesus, centering on the Sermon on the Mount, caused him in later life to become a fervent Christian anarchist and pacifist. His ideas on nonviolent resistance, expressed in such works as The Kingdom of God Is Within You, were to have a profound impact on such pivotal twentieth-century figures as Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. Tolstoy was born in Yasnaya Polyana, the family estate in the Tula region

of Russia. The Tolstoys were a well-known family of old Russian

nobility; he was connected to the grandest of Russian aristocracy. He

was the fourth of five children of Countess Mariya Tolstaya

(Volkonskaya). Tolstoy's parents died when he was young, so he and his

siblings were brought up by relatives. In 1844, he began studying law

and oriental languages at Kazan University.

His teachers described him as "both unable and unwilling to learn."

Tolstoy left university in the middle of his studies, returned to

Yasnaya Polyana and then spent much of his time in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. In 1851, after running up heavy gambling debts, he went with his elder brother to the Caucasus and joined the army. Around this time, he started writing. His

conversion from a dissolute and privileged society author to the

non-violent and spiritual anarchist of his latter days was brought

about by two trips around Europe in 1857 and 1860–61, a period when

many liberal-leaning Russian aristocrats escaped the stifling political

repression in Russia; others who followed the same path were Alexander Herzen, Mikhail Bakunin, and Peter Kropotkin.

During his 1857 visit, Tolstoy witnessed a public execution in Paris, a

traumatic experience that would mark the rest of his life. Writing in a

letter to his friend V. P. Botkin: The

truth is that the State is a conspiracy designed not only to exploit,

but above all to corrupt its citizens ... Henceforth, I shall never

serve any government anywhere. His European trip in 1860–61 shaped both his political and literary transformation when he met Victor Hugo, whose literary talents Tolstoy praised after reading Hugo's newly finished Les Miserables. A comparison of Hugo's novel and Tolstoy's War and Peace shows

the influence of the evocation of its battle scenes. Tolstoy's

political philosophy was also influenced by a March 1861 visit to

French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, then living in exile under an assumed name in Brussels. Apart from reviewing Proudhon's forthcoming publication, La Guerre et la Paix,

whose title Tolstoy would borrow for his masterpiece, the two men

discussed education, as Tolstoy wrote in his educational notebooks: If

I recount this conversation with Proudhon, it is to show that, in my

personal experience, he was the only man who understood the

significance of education and of the printing press in our time. Fired

by enthusiasm, Tolstoy returned to Yasnaya Polyana and founded thirteen

schools for his serfs' children, based on ground-breaking libertarian

principles Tolstoy described in his 1862 essay "The School at Yasnaya

Polyana". Tolstoy's educational experiments were short-lived due to

harassment by the Tsarist secret police, but as a direct forerunner to A.S. Neill's Summerhill School,

the school at Yasnaya Polyana can justifiably be claimed to be the

first example of a coherent theory of libertarian education. On 23 September 1862, Tolstoy married Sophia Andreevna Bers,

the daughter of a court physician, who was 16 years his junior. (Sonya,

the Russian dimunitive of Sofya, is the name that was used by her

family and friends) They had thirteen children, five of whom died during childhood. The

marriage was marked from the outset by sexual passion and emotional

insensitivity when Tolstoy, on the eve of their marriage, gave her his

diaries detailing his extensive sexual past and the fact that one of

the serfs on his estate had borne him a son. Even so, their early married life was ostensibly happy and allowed Tolstoy much freedom to compose the literary masterpieces War and Peace and Anna Karenina with Sonya acting as his secretary, proof-reader and financial manager. However, their later life together has been described by A.N. Wilson as

one of the unhappiest in literary history. His relationship with his

wife deteriorated as his beliefs became increasingly radical and he

sought to reject his inherited and earned wealth, including the

renunciation of the copyrights on his earlier works. Tolstoy is one of the giants of Russian literature. His most famous works include the novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina and novellas such as Hadji Murad and The Death of Ivan Ilyich. His contemporaries paid him lofty tributes. Dostoevsky thought him the greatest of all living novelists, while Flaubert exclaimed, "What an artist and what a psychologist!". Chekhov,

who often visited Tolstoy at his country estate, wrote, "When

literature possesses a Tolstoy, it is easy and pleasant to be a writer;

even when you know you have achieved nothing yourself and are still

achieving nothing, this is not as terrible as it might otherwise be,

because Tolstoy achieves for everyone. What he does serves to justify

all the hopes and aspirations invested in literature." Later critics and novelists continue to bear testament to Tolstoy's art. Virginia Woolf declared him the greatest of all novelists. James Joyce noted that, "He is never dull, never stupid, never tired, never pedantic, never theatrical!". Thomas Mann wrote

of Tolstoy's seemingly guileless artistry: "Seldom did art work so much

like nature". Such sentiments were shared by the likes of Proust, Faulkner and Nabokov. The latter heaped superlatives upon The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Anna Karenina; he questioned, however, the reputation of War and Peace, and sharply criticized Resurrection and The Kreutzer Sonata. Tolstoy's earliest works, the autobiographical novels Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth (1852–1856), tell of a rich landowner's son and his slow realization of the chasm between himself and his peasants.

Though he later rejected them as sentimental, a great deal of Tolstoy's

own life is revealed. They retain their relevance as accounts of the

universal story of growing up. Tolstoy served as a second lieutenant in an artillery regiment during the Crimean War, recounted in his Sevastapol Sketches. His experiences in battle helped stir his subsequent pacifism and gave him material for realistic depiction of war's horrors in his later work. His fiction consistently attempts to convey realistically the Russian society in which he lived. The Cossacks (1863) describes the Cossack life and people through a story of a Russian aristocrat in love with a Cossack girl. Anna Karenina (1877)

tells parallel stories of an adulterous woman trapped by the

conventions and falsities of society and of a philosophical landowner

(much like Tolstoy), who works alongside the peasants in the fields and

seeks to reform their lives. Tolstoy

not only drew from his experience of life but created characters in his

own image, such as Pierre Bezukhov and Prince Andrei in War and Peace, Levin in Anna Karenina and to some extent, Prince Nekhlyudov in Resurrection. Tolstoy's original idea for the novel War and Piece was to investigate the causes of the Decembrist revolt,

to which it refers only in the last chapters, from which can be deduced

that Andrei Bolkonski's son will become one of the Decembrists. The

novel explores Tolstoy's theory of history, and in particular the

insignificance of individuals such as Napoleon and Alexander. Somewhat

surprisingly, Tolstoy did not consider War and Peace to

be a novel (nor did he consider many of the great Russian fictions

written at that time to be novels). This view becomes less surprising

if one considers that Tolstoy was a novelist of the realist school who considered the novel to be a framework for the examination of social and political issues in nineteenth-century life. War and Peace (which is to Tolstoy really an epic in prose) therefore did not qualify. Tolstoy thought that Anna Karenina was his first true novel. After Anna Karenina, Tolstoy concentrated on Christian themes, and his later novels such as The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886) and What Is to Be Done? develop a radical anarcho-pacifist Christian philosophy which led to his excommunication from the Russian Orthodox Church in 1901. For all the praise showered on Anna Karenina and War and Peace, Tolstoy rejected the two works later in his life as something not as true of reality. Such an argument is supported in The Death of Ivan Ilyich,

whose main character continually battles with his family and servants,

demanding honesty above the water and food needed to sustain him. After reading Schopenhauer's The World as Will and Representation,

Tolstoy gradually became converted to the ascetic morality upheld in

that work as the proper spiritual path for the upper classes. In Chapter VI of A Confession,

Tolstoy quoted the final paragraph of Schopenhauer's work. It explained

how the nothingness that results from complete denial of self is only a

relative nothingness, and is not to be feared. The novelist was struck

by the description of Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu ascetic

renunciation as being the path to holiness. After reading passages in Schopenhauer's ethical chapters, the

Russian nobleman chose poverty and formal denial of the will. Tolstoy's Christian beliefs centered on the Sermon on the Mount, particularly the injunction to turn the other cheek, which he saw as a justification for pacifism, nonviolence and nonresistance.

Various versions of "Tolstoy's Bible" have been published, indicating

the passages Tolstoy most relied on, specifically, the reported words

of Jesus himself. Tolstoy

believed being a Christian required him to be a pacifist; the

consequences of being a pacifist, and the apparently inevitable waging

of war by government, made him a philosophical anarchist. Tolstoy believed that a true Christian could find lasting happiness by striving for inner self-perfection through following the Great Commandment of loving one's neighbor and God rather than looking outward to the Church or state for guidance and meaning. His belief in nonresistance (nonviolence) when faced by conflict is another distinct attribute of his philosophy based on Christ's teachings. By directly influencing Mahatma Gandhi with this idea through his work The Kingdom of God is Within You,

Tolstoy has had a huge influence on the nonviolent resistance movement

to this day. He believed that the aristocracy were a burden on the

poor, and that the only solution to how we live together is through anarchism. He also opposed private property and the institution of marriage and valued the ideals of chastity and sexual abstinence (discussed in Father Sergius and his preface to The Kreutzer Sonata), ideals also held by the young Gandhi. Tolstoy's later work is often criticised as being overly didactic and patchily written, but derives a passion and verve from the depth of his austere moral views. The sequence of the temptation of Sergius in Father Sergius,

for example, is among his later triumphs. Gorky relates how Tolstoy

once read this passage before himself and Chekhov and that Tolstoy was

moved to tears by the end of the reading. Other later passages of rare

power include the crises of self faced by the protagonists of The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Master and Man,

where the main character in the former or the reader in the latter is

made aware of the foolishness of the protagonists' lives. Tolstoy had a profound influence on the development of anarchist thought. The Tolstoyans were

a small Christian anarchist group formed by Tolstoy's companion,

Vladimir Chertkov (1854–1936), in order to spread Tolstoy's religious

teachings. In

hundreds of essays over the last twenty years of his life, Tolstoy

reiterated the anarchist critique of the State and recommended books by Kropotkin and Proudhon to his readers, whilst rejecting anarchism's espousal of violent revolutionary means. Despite his misgivings about anarchist violence, Tolstoy took risks to circulate the prohibited publications of anarchist thinkers in Russia, and corrected the proofs of Kropotkin's "Words of a Rebel", illegally published in St Petersburg in 1906. A letter Tolstoy wrote in 1908 to an Indian newspaper entitled "A Letter to a Hindu" resulted in intense correspondence with Mohandas Gandhi, who was in South Africa at the time and was beginning to become an activist. Reading The Kingdom of God is Within You had convinced Gandhi to abandon violence and espouse nonviolent resistance,

a debt Gandhi acknowledged in his autobiography, calling Tolstoy "the

greatest apostle of non-violence that the present age has produced".

The correspondence between Tolstoy and Gandhi would only last a year,

from October 1909 until Tolstoy's death in November 1910, but led

Gandhi to give the name the Tolstoy Colony to his second ashram in

South Africa. Besides non-violent resistance, the two men shared a common belief in the merits of vegetarianism, the subject of several of Tolstoy's essays. Along with his growing idealism, Tolstoy also became a major supporter of the Esperanto movement. Tolstoy was impressed by the pacifist beliefs of the Doukhobors and

brought their persecution to the attention of the international

community, after they burned their weapons in peaceful protest in 1895.

He aided the Doukhobors in migrating to Canada. In 1904, during the Russo-Japanese War, Tolstoy condemned the war and wrote to the Japanese Buddhist priest Soyen Shaku in a failed attempt to make a joint pacifist statement. Tolstoy

was a wealthy member of the Russian nobility. He came to believe that

he was undeserving of his inherited wealth, and was renowned among the

peasantry for his generosity. He would frequently return to his country

estate with vagrants whom he felt needed a helping hand, and would

often dispense large sums of money to street beggars while on trips to

the city, much to his wife's chagrin.

Tolstoy died of pneumonia at Astapovo station in 1910 after

leaving home in the middle of winter at the age of 82. His death came

only days after gathering the nerve to abandon his family and wealth and take up the path of a wandering ascetic; a

path that he had agonized over pursuing for decades. He had not been at

the peak of health before leaving home, his wife and daughters were all

actively engaged in caring for him daily. He had been speaking and

writing of his own death in the days preceding his departure from home,

but fell ill at the train station not far from home. The station master

took Tolstoy to his apartment, where his personal doctors were called

to the scene. He was given injections of morphine and camphor. The

police tried to limit access to his funeral procession, but thousands

of peasants lined the streets at his funeral. Still, some peasants were

heard to say that, other than knowing that "some nobleman had died,"

they knew little else about Tolstoy.