<Back to Index>

- Astronomer William Cranch Bond, 1789

- Novelist Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, 1828

- 1st Chief Minister of the French King Armand Jean du Plessis, Cardinal-Duc de Richelieu, 1585

Armand Jean du Plessis de Richelieu, Cardinal-Duc de Richelieu (9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642) was a French clergyman, noble, and statesman.

Consecrated as a bishop in 1608, he later entered politics, becoming a Secretary of State in 1616. Richelieu soon rose in both the Church and the state, becoming a cardinal in 1622, and King Louis XIII's chief minister in 1624. He remained in office until his death in 1642; he was succeeded by Cardinal Mazarin, whose career he fostered. The

Cardinal de Richelieu was often known by the title of the King's "Chief

Minister" or "First Minister." As a result, he is considered to be the

world's first Prime Minister, in the modern sense of the term. He sought to consolidate royal power and crush domestic factions. By restraining the power of the nobility, he transformed France into a strong, centralized state. His chief foreign policy objective was to check the power of the Austro-Spanish Habsburg dynasty. Although he was a cardinal, he did not hesitate to make alliances with Protestant rulers in attempting to achieve this goal. His tenure was marked by the Thirty Years' War that engulfed Europe. Richelieu was also famous for his patronage of the arts; most notably, he founded the Académie Française, the learned society responsible for matters pertaining to the French language. Richelieu is also known by the sobriquet l'Éminence rouge ("the Red Eminence"), from the red shade of a cardinal's vestments and the style "eminence" as a cardinal. As an advocate for Samuel de Champlain and of the retention of Quebec, he founded the Compagnie des Cent-Associés and saw the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye return Quebec City to French rule under Champlain, after the settlement had been captured by the Kirkes in 1629. This in part allowed the colony to eventually develop into the heartland of Francophone culture in North America. He is also a leading character in The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas, père, and its subsequent film adaptations, portrayed as a main antagonist, and a powerful ruler, even more powerful than the King himself, though events like the Day of the Dupes show that in fact he very much depended on the King's confidence to keep this power. Born in Paris,

Richelieu was the fourth of five children and the last of three sons.

His family, although belonging only to the lesser nobility of Poitou, was

somewhat prominent: his father, François du Plessis, seigneur de

Richelieu, was a soldier and courtier who served as the Grand Provost of France; his mother, Susanne de La Porte, was the daughter of a famous jurist. When he was five years old, his father died fighting in the French Wars of Religion, leaving the family in debt; with the aid of royal grants, however, the family was able to avoid financial difficulties. At the age of nine, young Richelieu was sent to the College of Navarre in Paris to study philosophy. Thereafter, he began to train for a military career. King Henry III had rewarded Richelieu's father for his participation in the Wars of Religion by granting his family the bishopric of Luçon. The

family appropriated most of the revenues of the bishopric for private

use; they were, however, challenged by clergymen who desired the funds

for ecclesiastical purposes. In order to protect the important source of revenue, Richelieu's mother proposed to make her second son, Alphonse, the bishop of Luçon. Alphonse, who had no desire to become a bishop, instead became a Carthusian monk. Thus,

it became necessary that the younger Richelieu join the clergy. As a

frail and sickly child who preferred academic interests, he was not

averse to the prospect. In 1606 King Henry IV nominated Richelieu to become Bishop of Luçon. As Richelieu had not yet reached the official minimum age, it was necessary he journey to Rome for a special dispensation from the Pope.

This secured, Richelieu was consecrated bishop in April, 1607. Soon

after he returned to his diocese in 1608, Richelieu was heralded as a reformer. He became the first bishop in France to implement the institutional reforms prescribed by the Council of Trent between 1545 and 1563. At about this time, Richelieu became a friend of François Leclerc du Tremblay (better known as "Père Joseph" or "Father Joseph"), a Capuchin friar,

who would later become a close confidant. Because of his closeness to

Richelieu, and the grey colour of his robes, Father Joseph was also

nicknamed l'Éminence grise ("the Grey Eminence"). Later, Richelieu often used him as an agent during diplomatic negotiations. In 1614, the clergymen of Poitou demanded Richelieu to be one of their representatives to the States-General. There, he was a vigorous advocate of the Church, arguing that it should be exempt from taxes and

that bishops should have more political power. He was the most

prominent clergyman to support the adoption of the decrees of the

Council of Trent throughout France; the Third Estate (commoners) was his chief opponent in this endeavour. At the end of the assembly, the First Estate (the clergy) chose him to deliver the address enumerating its petitions and decisions. Soon after the dissolution of the Estates-General, Richelieu entered the service of King Louis XIII's wife, Anne of Austria, as her almoner. Richelieu advanced politically by faithfully serving the Queen's favourite, Concino Concini, the most powerful minister in the kingdom. In 1616, Richelieu was made Secretary of State, and was given responsibility for foreign affairs. Like Concini, the Bishop was one of the closest advisors of Louis XIII's mother, Marie de Médicis.

The Queen had become Regent of France when the nine-year old Louis

ascended the throne; although her son reached the legal age of majority

in 1614, she remained the effective ruler of the realm. However,

her policies, and those of Concini, proved unpopular with many in

France. As a result, both Marie and Concini became the targets of

intrigues at court; their most powerful enemy was Charles de Luynes. In

April 1617, in a plot arranged by Luynes, King Louis XIII ordered that

Concini be arrested, and killed should he resist; Concini was

consequently assassinated, and Marie de Médicis overthrown. His patron having died, Richelieu also lost power; he was dismissed as Secretary of State, and was removed from the court. In 1618, the King, still suspicious of the Bishop of Luçon, banished him to Avignon. There, Richelieu spent most of his time writing; he composed a catechism entitled L'Instruction du chrétien. In 1619, Marie de Médicis escaped from her confinement in the Château de Blois,

becoming the titular leader of an aristocratic rebellion. The King and

the duc de Luynes recalled Richelieu, believing that he would be able

to reason with the Queen. Richelieu was successful in this endeavour,

mediating between her and her son. Complex negotiations bore fruit when the Treaty of Angoulême was

ratified; Marie de Médicis was given complete freedom, but would

remain at peace with the King. The Queen was also restored to the royal

council. After the death of the King's favourite, the duc de Luynes, in 1621, Richelieu began to rise to power quickly. Next year, the King nominated Richelieu for a cardinalate, which Pope Gregory XV accordingly granted on 19 April 1622. Crises in France, including a rebellion of the Huguenots,

rendered Richelieu a nearly indispensable advisor to the King. After he

was appointed to the royal council of ministers in April 1624, he

intrigued against the chief minister, Charles, duc de La Vieuville. In

August of the same year, La Vieuville was arrested on charges of

corruption, and Cardinal Richelieu took his place as the King's

principal minister. Cardinal Richelieu's policy involved two primary goals: centralization of power in France and opposition to the Habsburg dynasty (which ruled in both Austria and Spain). Shortly after he became Louis' principal minister, he was faced with a crisis in Valtellina, a valley in Lombardy (northern Italy). In order to counter Spanish designs on the territory, Richelieu supported the Protestant Swiss canton of Grisons,

which also claimed the strategically important valley. The Cardinal

deployed troops to Valtellina, from which the Pope's garrisons were

driven out. Richelieu's

early decision to support a Protestant canton against the Pope was a

foretaste of the purely diplomatic power politics he would espouse in

his foreign policy. In order to further consolidate power in France, Richelieu sought to suppress the influence of the feudal nobility. In 1626, he abolished the position of Constable of France and ordered all fortified castles to be razed, excepting only those needed to defend against invaders. Thus,

he stripped the princes, dukes, and lesser aristocrats of important

defences that could have been used against the King's armies during

rebellions. As a result, Richelieu was hated by most of the nobility.

Another obstacle to the centralization of power was religious division

in France. The Huguenots,

one of the largest political and religious factions in the country,

controlled a significant military force, and were in rebellion. Moreover, the King of England, Charles I,

declared war on France in an attempt to aid the Huguenot faction. In

1627, Richelieu ordered the army to besiege the Huguenot stronghold of La Rochelle; the Cardinal personally commanded the besieging troops. English troops under the Duke of Buckingham led

an expedition to help the citizens of La Rochelle, but failed

abysmally. The city, however, remained firm for over a year before

capitulating in 1628. Although the Huguenots suffered a major defeat at La Rochelle, they continued to fight, led by Henri, duc de Rohan. Protestant forces, however, were defeated in 1629; Rohan submitted to the terms of the Peace of Alais. As a result, religious toleration for Protestants, which had first been granted by the Edict of Nantes in 1598, was permitted to continue; however, the Cardinal abolished their political rights and protections. Rohan

was not executed (as were leaders of rebellions later in Richelieu's

tenure); in fact, he later became a commanding officer in the French

army. Habsburg

Spain exploited the French conflict with the Huguenots to extend its

influence in northern Italy. It funded the Huguenot rebels in order to

keep the French army occupied, meanwhile expanding its Italian dominions.

Richelieu, however, responded aggressively; after La Rochelle

capitulated, he personally led the French army to northern Italy to

restrain Spain. In

the next year, Richelieu's position was seriously threatened by his

former patron, Marie de Médicis. Marie believed that the

Cardinal had robbed her of her political influence; thus, she demanded

that her son dismiss the chief minister. Louis XIII was not, at first, averse to such a course of action, as he personally disliked Richelieu. The

persuasive statesman convinced his master of the wisdom in his plans,

however. On 11 November 1630, Marie de Médicis and the King's

brother, Gaston, duc d'Orléans,

secured the King's agreement for the dismissal. Richelieu, however, was

aware of the plan, and quickly convinced the King to repent. This day, known as the Day of the Dupes,

was the only one on which Louis XIII took a step toward dismissing his

minister. Thereafter, the King was unwavering in his political support

for him; the courtier was created duc de Richelieu and was made a Peer of France. Meanwhile, Marie de Médicis was exiled to Compiègne.

Both Marie and the duc d'Orléans continued to conspire against

Richelieu, but their schemes came to nothing. The nobility, also,

remained powerless. The only important rising was that of Henri, duc de Montmorency in

1632; Richelieu, ruthless in suppressing opposition, ordered the duke's

execution. Richelieu's harsh measures were designed to intimidate his

enemies. He also ensured his political security by establishing a large

network of spies in France as well as in other European countries. Before Richelieu's ascent to power, most of Europe had become involved in the Thirty Years' War. France was not openly at war with the Habsburgs, who ruled Spain and the Holy Roman Empire, so subsidies and aid were given secretly to their adversaries. He subsidized the Dutch to fight against the Spanish via the Treaty of Compiègne in 1624. That same year, a military expedition, secretly financed by France and commanded by Marquis de Coeuvres, liberated the Valtelline of Spanish occupation. In 1625 Richelieu also sent money to Ernst von Mansfeld, a famous mercenary general operating in Germany in English service. However, in 1626, he made peace with Spain via the Treaty of Monçon. This peace quickly broke after tensions due to the War of Mantuan Succession. In 1629, the Emperor Ferdinand II subjugated many of his Protestant opponents in Germany. Richelieu, alarmed by Ferdinand's influence, incited Sweden to intervene, providing money. In

the meantime, France and Spain remained hostile over Spain's ambitions

in northern Italy. At that time northern Italy was a major strategic

item in Europe's balance of powers, serving as a link between the

Habsburgs in the Empire and in Spain. Had the imperial armies dominated

this region, France's very existence would have been endangered, as it

would have been encircled by Habsburg territories. Spain was seeking

papal approval for a "universal monarchy." When, in 1630, French

ambassadors in Regensburg agreed to make peace with Spain, Richelieu refused to uphold them. The

agreement would have prohibited French interference in Germany. Thus,

Richelieu advised Louis XIII to refuse to ratify the treaty. In 1631,

he allied France to Sweden, who had just invaded the empire, in the Treaty of Bärwalde. Military expenses put a considerable strain on the King's revenues. In response, Richelieu raised the gabelle (salt tax) and the taille (land tax). The taille was enforced to provide funds to raise armies and wage war. The clergy, nobility, and high bourgeoisie were

either exempt or could easily avoid payment, so the burden fell on the

poorest segment of the nation. To collect taxes more efficiently, and

to keep corruption to a minimum, Richelieu bypassed local tax

officials, replacing them with intendants (officials in the direct service of the Crown). Richelieu's financial scheme, however, caused unrest among the peasants; there were several uprisings in 1636 to 1639. Richelieu crushed the revolts violently, and dealt with the rebels harshly. Because

he openly aligned France with Protestant powers, Richelieu was

denounced by many as a traitor to the Roman Catholic Church. Military

hostilities, at first, were disastrous for the French, with many

victories going to Spain and the Empire. Neither

side, however, could obtain a decisive advantage, and the conflict

lingered on until after Richelieu's death. Richelieu was instrumental

in redirecting the 30 Years' War from the conflict of Protestantism

versus Catholicism to that of nationalism versus Habsburg hegemony. In

this conflict France effectively drained the already overstretched

resources of the Habsburg empire and drove it inexorably towards

bankruptcy. The defeat of Habsburg forces at the Battle of Lens, and their failure to prevent French invasion of Catalonia effectively spelled the end for Habsburg domination of the continent, and Olivares' personal career. Indeed, in the subsequent years it would be France, under the leadership of Louis XIV,

who would attempt to fill the vacuum left by the Habsburgs in the

Spanish Netherlands, and supplant Spain as the dominant European power. Towards the end of his life, Richelieu alienated many people, including Pope Urban VIII. Richelieu was displeased by the Pope's refusal to name him the papal legate in France; in turn, the Pope did not approve of the administration of the French church, or of French foreign policy. However, the conflict was largely healed when the Pope granted a cardinalate to Jules Mazarin,

one of Richelieu's foremost political allies, in 1641. Despite troubled

relations with the Roman Catholic Church, Richelieu did not support the

complete repudiation of papal authority in France, as was advocated by

the Gallicanists. As

he neared his death, Richelieu faced a plot that threatened to remove

him from power. The cardinal had introduced a young man named Henri Coiffier de Ruzé, marquis de Cinq-Mars to Louis XIII's court. The Cardinal had been a friend of Cinq-Mars' father. More

importantly, Richelieu hoped that Cinq-Mars would become Louis'

favourite, so that he could indirectly exercise greater influence over

the monarch's decisions. Cinq-Mars had become the royal favourite by

1639, but, contrary to Cardinal Richelieu's belief, he was not easy to

control. The young marquis realized that Richelieu would not permit him

to gain political power. In 1641, he participated in the comte de Soissons' failed conspiracy against Richelieu, but was not discovered. Next

year, he schemed with leading nobles (including the King's brother, the

duc d'Orléans) to raise a rebellion; he also signed a secret

agreement with the King of Spain, who promised to aid the rebels. Richelieu's spy service, however, discovered the plot, and the Cardinal received a copy of the treaty. Cinq-Mars

was promptly arrested and executed; although Louis approved the use of

capital punishment, he grew more distant from Richelieu as a result.

In the same year, however, Richelieu's health was already failing, due to chronic pulmonary tuberculosis.

He also suffered greatly from eye strain and headaches. As he felt his

death approaching, he named as his successor one of his most faithful

followers, Jules Mazarin. Although Mazarin was originally a representative of the Holy See,

he had left the Pope's service to join that of the King of France.

Mazarin succeeded Richelieu when the latter died. Richelieu is interred at the church of the Sorbonne. Richelieu was a famous patron of the arts. Himself an author of various religious and political works (most notably his Political Testament), he sent his agents abroad in

search of books and manuscripts for his unrivaled library, which he

specified in his will, leaving it to his great-nephew fully funded,

should serve, not merely his family but to be open at fixed hours to

scholars; the manuscripts alone numbered some 900, bound as codices in

red Morocco with the cardinal's arms. The library was transferred to

the Sorbonne in 1660. He funded the literary careers of many writers. He was a lover of the theatre,

which was not considered a respectable art form during that era; a

private theatre was a feature of the Palais-Cardinal. Among the

individuals he patronized was the famous playwright Pierre Corneille. Richelieu was also the founder and patron of the Académie française, the pre-eminent French literary society. The institution had previously been in informal existence; in 1635, however, Cardinal Richelieu obtained official letters patent for

the body. The Académie française includes forty members,

promotes French literature, and continues to be the official authority

on the French language. Richelieu served as the Académie's

"protector"; since 1672, that role has been fulfilled by the French

head of state. In 1622, Richelieu was elected the proviseur or principal of the Sorbonne. He presided over the renovation of the college's buildings, and over the construction of its famous chapel, where he is now entombed. As he was Bishop of Luçon, his statue stands outside the Luçon cathedral. Richelieu oversaw the construction of his own palace in Paris, the Palais-Cardinal. The palace, renamed the Palais Royal after Richelieu's death, now houses the French Constitutional Council, the Ministry of Culture, and the Conseil d'État. The Galerie de l'avant-cour had ceiling paintings by the Cardinal's chief portraitist, Philippe de Champaigne, celebrating the major events of the Cardinal's career; the Galerie des hommes illustres had twenty-six historicizing portraits of great men, larger than life, from Abbot Suger to Louis XIII; some were by Simon Vouet others were careful copies by Philippe de Champaigne from known portraits; with

them were busts of Roman emperors. Another series of portraits of

authors complemented the library. The architect of the Palais-Cardinal, Jacques Lemercier, also received a commission to build a château and a surrounding town in Indre-et-Loire;

the project culminated in the construction of the Château

Richelieu and the town of Richelieu. To the château, he added one

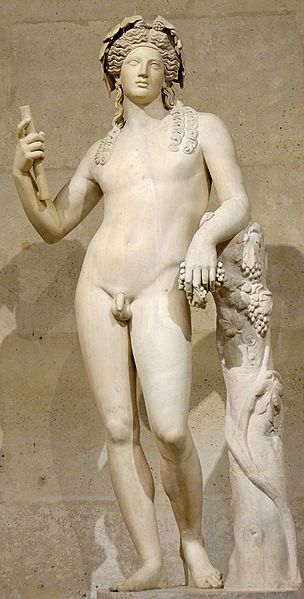

of the largest art collections in Europe and the largest collection of ancient Roman sculpture in France. The heavily resurfaced and restored Richelieu Bacchus continued to be admired by neoclassical artists. Among his 300 paintings by moderns, most notably, he owned Leonardo's Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, The Family of the Virgin by Andrea del Sarto, the two famous Bacchanales of Nicolas Poussin, as well as paintings by Veronese and Titian, and Diana at the Bath by Rubens, for which he was so glad to pay the artist's heirs 3000 écus, that he made a gift to Rubens' widow of a diamond-encrusted watch. His marble portrait bust by Bernini was not considered a good likeness and was banished to a passageway. The

fittings of his chapel in the Palais-Cardinal, for which Simon Vouet

executed the paintings, were of solid gold — crucifix, chalice, patten,

ciborium, candelsticks — set with 180 rubies and 9000 diamonds. His taste also ran to massive silver, small bronzes and works of vertu,

enamels and rock crystal mounted in gold, Chinese porcelains,

tapestries and Persian carpets, cabinets from Italy and Antwerp and the

heart-shaped diamond bought from Alphonse Lopez that he willed to the

king. when the Palais-Cardinal was complete, he donated it to the

Crown, in 1636. With the Queen in residence, the paintings of the Grand Cabinet were transferred to Fontainebleau and replaced by copies, and the interiors were subjected to much rearrangement. Michelangelo's two Slaves were among the rich appointments of the château Richelieu, where there were the Nativity triptych by Dürer and paintings by Mantegna, Lorenzo Costa and Perugino, lifted from the Gonzaga collection at Mantua by French military forces in 1630, as well as numerous antiquities.