<Back to Index>

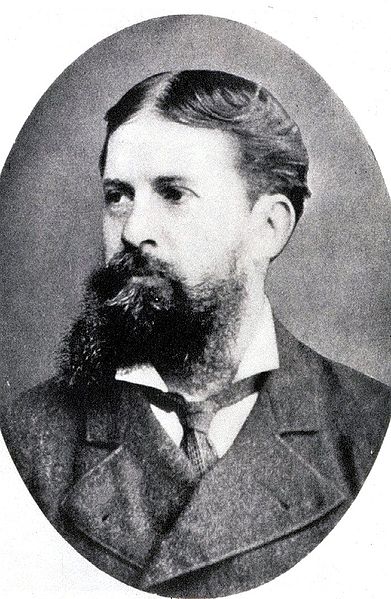

- Philosopher and Mathematician Charles Sanders Peirce, 1839

- Architect Sir John Soane, 1753

- President of Mexico Nicolás Bravo Rueda, 1786

Charles Sanders Peirce (September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American philosopher, logician, mathematician, and scientist, born in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Peirce was educated as a chemist and employed as a scientist for 30 years. It is largely his contributions to logic, mathematics, philosophy, and semiotics (and his founding of pragmatism) that are appreciated today. In 1934, the philosopher Paul Weiss called Peirce "the most original and versatile of American philosophers and America's greatest logician".

An innovator in many fields — including philosophy of science, epistemology, metaphysics, mathematics, statistics, research methodology, and the design of experiments in astronomy, geophysics, and psychology — Peirce considered himself a logician first

and foremost. He made major contributions to logic, but logic for him

encompassed much of that which is now called epistemology and

philosophy of science. He saw logic as the formal branch of semiotics,

of which he is a founder. As early as 1886 he saw that logical

operations could be carried out by electrical switching circuits, an

idea used decades later to produce digital computers. Charles Sanders Peirce was the son of Sarah Hunt Mills and Benjamin Peirce, a professor of astronomy and mathematics at Harvard University, perhaps the first serious research mathematician in America. At 12 years of age, Charles read an older brother's copy of Richard Whately's Elements of Logic,

then the leading English language text on the subject. Thus began his

lifelong fascination with logic and reasoning. He went on to obtain the

BA and MA from Harvard. In 1863 the Lawrence Scientific School awarded him, summa cum laude, its first M.Sc. in chemistry; otherwise his academic record was undistinguished. At Harvard, he began lifelong friendships with Francis Ellingwood Abbot, Chauncey Wright, and William James. One of his Harvard instructors, Charles William Eliot,

formed an unfavorable opinion of Peirce. This opinion proved fateful,

because Eliot, while President of Harvard 1869–1909 — a period

encompassing nearly all of Peirce's working life — repeatedly vetoed

having Harvard employ Peirce in any capacity. Peirce

suffered from his late teens through the rest of his life from

something then known as "facial neuralgia", a very painful

nervous/facial condition, which would today be diagnosed as trigeminal neuralgia. The biography by Joseph Brent says

that when in the throes of its pain "he was, at first, almost

stupefied, and then aloof, cold, depressed, extremely suspicious,

impatient of the slightest crossing, and subject to violent outbursts

of temper." Its consequences may have led to the social isolation which

made his life's later years so tragic. Between 1859 and 1891, Peirce was intermittently employed in various scientific capacities by the United States Coast Survey, where he enjoyed the protection of his highly influential father until

the latter's death in 1880. This employment exempted Peirce from having

to take part in the Civil War. It would have been very awkward for him to do so, as the Boston Brahmin Peirces sympathized with the Confederacy. At the Survey, he worked mainly in geodesy and in gravimetry, refining the use of pendulums to determine small local variations in the strength of Earth's gravity. The Survey sent him to Europe five times, first in 1871, as part of a group dispatched to observe a solar eclipse. While in Europe, he sought out Augustus De Morgan, William Stanley Jevons, and William Kingdon Clifford,

British mathematicians and logicians whose turn of mind resembled his

own. From 1869 to 1872, he was employed as an Assistant in Harvard's

astronomical observatory, doing important work on determining the

brightness of stars and the shape of the Milky Way. In 1876 he was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences. In 1878, he was the first to define the meter as so many wavelengths of light of a certain frequency, the definition employed until 1983. During

the 1880s, Peirce's indifference to bureaucratic detail waxed while the

quality and timeliness of his Survey work waned. Peirce took years to

write reports that he should have completed in mere months. Meanwhile,

he wrote hundreds of logic, philosophy, and science entries for the Century Dictionary. In 1885, an investigation by the Allison Commission exonerated Peirce, but led to the dismissal of Superintendent Julius Hilgard and

several other Coast Survey employees for misuse of public funds. In

1891, Peirce resigned from the Coast Survey, at the request of

Superintendent Thomas Corwin Mendenhall. He never again held regular employment. In 1879, Peirce was appointed Lecturer in logic at the new Johns Hopkins University. That university was strong in a number of areas that interested him, such as philosophy (Royce and Dewey did their PhDs at Hopkins), psychology (taught by G. Stanley Hall and studied by Joseph Jastrow, who coauthored a landmark empirical study with Peirce), and mathematics (taught by J.J. Sylvester,

who came to admire Peirce's work on mathematics and logic). This

non tenured position proved to be the only academic appointment Peirce

ever held. Brent

documents something Peirce never suspected, namely that his efforts to

obtain academic employment, grants, and scientific respectability were

repeatedly frustrated by the covert opposition of a major American

scientist of the day, Simon Newcomb.

Peirce's ability to find academic employment may also have been

frustrated by a difficult personality. Brent conjectures about various

psychological and other difficulties. Peirce's

personal life also handicapped him. His first wife, Harriet Melusina

Fay, left him in 1875. He soon took up with a woman, Juliette,

whose maiden name and nationality remain uncertain to this day (the

best guess is that her name was Juliette Froissy and that she was

French), but his divorce from Harriet became final only in 1883, after

which he married Juliette. That year, Newcomb pointed out to a Johns

Hopkins trustee that Peirce, while a Hopkins employee, had lived and

traveled with a woman to whom he was not married. The ensuing scandal

led to his dismissal. Just why Peirce's later applications for academic

employment at Clark University, University of Wisconsin–Madison, University of Michigan, Cornell University, Stanford University, and the University of Chicago were

all unsuccessful can no longer be determined. Presumably, his having

lived with Juliette for years while still legally married to Harriet

led him to be deemed morally unfit for academic employment anywhere in

the USA. Peirce had no children by either marriage. In 1887 Peirce spent part of his inheritance from his parents to buy 2,000 acres (8 km2) of rural land near Milford, Pennsylvania, land which never yielded an economic return. There he built a large house which he named "Arisbe"

where he spent the rest of his life, writing prolifically, much of it

unpublished to this day. His living beyond his means soon led to grave

financial and legal difficulties. Peirce spent much of his last two

decades unable to afford heat in winter, and subsisting on old bread

donated by the local baker. Unable to afford new stationery, he wrote

on the verso side

of old manuscripts. An outstanding warrant for assault and unpaid debts

led to his being a fugitive in New York City for a while. Several

people, including his brother James Mills Peirce and his neighbors, relatives of Gifford Pinchot, settled his debts and paid his property taxes and mortgage. Peirce

did some scientific and engineering consulting and wrote a good deal

for meager pay, mainly dictionary and encyclopedia entries, and reviews

for The Nation (with whose editor, Wendell Phillips Garrison, he became friendly). He did translations for the Smithsonian Institution, at its director Samuel Langley's

instigation. Peirce also did substantial mathematical calculations for

Langley's research on powered flight. Hoping to make money, Peirce

tried inventing. He began but did not complete a number of books. In

1888, President Grover Cleveland appointed him to the Assay Commission. From 1890 onwards, he had a friend and admirer in Judge Francis C. Russell of Chicago, who introduced Peirce to Paul Carus and Edward Hegeler, the editor and the owner, respectively, of the pioneering American philosophy journal The Monist, which eventually published 14 or so articles by Peirce. He applied to the newly formed Carnegie Institution for

a grant to write a book summarizing his life's work. The application

was doomed; his nemesis Newcomb served on the Institution's executive

committee, and its President had been the President of Johns Hopkins at

the time of Peirce's dismissal. The one who did the most to help Peirce in these desperate times was his old friend William James, dedicating his Will to Believe (1897) to Peirce, and arranging for Peirce to be paid to give two series of lectures at or near Harvard (1898 and 1903).

Most important, each year from 1907 until James's death in 1910, James

wrote to his friends in the Boston intelligentsia, asking that they

contribute financially to help support Peirce; the fund continued even

after James's death in 1910. Peirce reciprocated by designating James's

eldest son as his heir should Juliette predecease him. It

has also been believed that this was why Peirce used "Santiago" ("St.

James" in Spanish) as a middle name, but he appeared in print as early

as 1890 as Charles Santiago Peirce. Peirce died destitute in Milford, Pennsylvania, twenty years before his widow.