<Back to Index>

- Chemist Irène Joliot-Curie, 1897

- Painter and Photographer George Hendrik Breitner, 1857

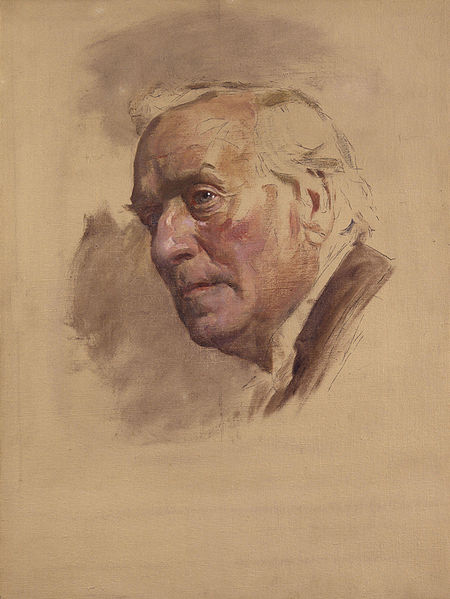

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Herbert Henry Asquith, 1852

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, KG, PC, KC (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) served as the Liberal Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the longest continuously serving Prime Minister in the twentieth century until early 1988, when his record was surpassed by Margaret Thatcher.

As Prime Minister, he led his Liberal party to a series of domestic reforms, including social insurance and the reduction of the power of the House of Lords. He led the nation into The First World War, but a series of military and political crises led to his replacement in late 1916 by David Lloyd George.

His falling out with Lloyd George played a major part in the downfall

of the Liberal Party. Before his term as Prime Minister he served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1905 to 1908 and as Home Secretary from 1892 to 1895. During his lifetime he was known as H. H. Asquith before his accession to the peerage and as Lord Oxford afterwards. Asquith's

achievements in peacetime have been overshadowed by his weaknesses in

wartime. Many historians portray a vacillating prime minister, unable

to present the necessary image of action and dynamism to the public. Others stress

his continued high administrative ability. The dominant historical

verdict is that there were two Asquiths: the urbane and conciliatory

Asquith who was a successful peacetime leader and the hesitant and

increasingly exhausted Asquith who practiced the politics of muddle and

delay during the World War. He was born in Morley, West Yorkshire,

England to Joseph Dixon Asquith (10 February 1825 - 29 March 1860) and

his wife Emily Willans (4 May 1828 - 12 December 1888). The Asquiths

were a middle class family and members of the Congregational church.

Joseph was a wool merchant and came to own his own woolens mill.

Herbert was seven years old when his father died. Emily and her

children moved to the house of her father William Willans, a wool-stapler of Huddersfield. Herbert received schooling there and was later sent to a Moravian Church boarding school at Fulneck, near Leeds. In 1863, Herbert was sent to live with an uncle in London, where he entered the City of London School. He was educated there until 1870 and mentored by its headmaster Edwin Abbott Abbott. In 1870, Asquith won a classical scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford.

In 1874, Asquith was awarded the Craven scholarship. Despite the

unpopularity of the Liberals during the dying days of Gladstone's First

Government, he became president of the Oxford Union in the Trinity (summer) term of his fourth year. He graduated that year and soon was elected a fellow at Balliol. Meanwhile he entered Lincoln's Inn as a pupil barrister and for a year served a pupillage under Charles Bowen. He was called to the bar in 1876 and became prosperous in the early 1880s from practising at the chancery bar. Among other cases he appeared for the defence in the famous case of Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. Asquith took silk and was appointed QC in 1890. It was at Lincoln's Inn that in 1882 Asquith met Richard Haldane, whom he would appoint as Lord Chancellor in 1912. In

his younger days he was called Herbert within the family, but his

second wife called him Henry; his biographer Stephen Koss entitled the

first chapter of his biography "From Herbert to Henry", referring to

upward social mobility and his abandonment of his Yorkshire

Nonconformist roots with his second marriage. However, in public he was

invariably referred to only as H. H. Asquith. "There have been few major national figures whose Christian names were less well known to the public," writes his biographer, Roy Jenkins. His opponents gave him the nickname "Squiff" or "Squiffy", a derogatory reference to his fondness for drink. When

raised to the peerage in 1925, he proposed to take the title "Earl of

Oxford" for the city near which he lived and the university he had

attended. Objections were raised, especially by descendants of Earls of

Oxford of previous creations (titles by then extinct, eg. Robert Harley, Earl of Oxford, a leading Tory statesman of Queen Anne's reign), and his title was given in the form Earl of Oxford and Asquith. In practice, however, he was known as Lord Oxford, which some wags said was "like a suburban villa calling itself 'Versailles'." He

married Helen Kelsall Melland, daughter of a Manchester doctor, in

1877, and they had four sons and one daughter before she died from typhoid fever in 1891. These children were Raymond (1878-1916), Herbert (1881-1947), Arthur (1883–1939), Violet (1887-1969), and Cyril (1890-1954). Of these children, Violet and Cyril became life peers in their own right, Cyril becoming a law lord. In 1894, he married Margot Tennant, a daughter of Sir Charles Tennant, 1st Bt.. They had two children, Elizabeth Charlotte Lucy (later Princess Antoine Bibesco) (1897-1945) and the film director Anthony (1902-1968). In 1912, Asquith fell in love with Venetia Stanley, and his romantic obsession with her continued into 1915, when she married Edwin Montagu,

a Liberal Cabinet Minister; a volume of Asquith's letters to Venetia,

often written during Cabinet meetings and describing political business

in some detail, has been published, but it is not known whether or not

their relationship was sexually consummated. All his children, except

Anthony, married and left issue. His best-known descendant today is the

actress Helena Bonham Carter, a granddaughter of Violet. Asquith was elected to Parliament in 1886 as the Liberal representative for East Fife, in Scotland. He never served as a junior minister, but achieved his first significant post in 1892 when he became Home Secretary in the fourth cabinet of Gladstone. He retained his position when Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, took over in 1894. The Liberals lost power in the 1895 general election and

for ten years were in opposition. In 1898 he was offered and turned

down the opportunity to lead the Liberal Party, then deeply divided and

unpopular, preferring to use the opportunity to earn money as a

barrister. During Asquith's period as deputy to the new leader Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman,

"C.B." was known to request his presence in parliamentary debate by

saying, "Send for the sledge-hammer," referring to Asquith's reliable

command of facts and his ability to dominate verbal exchange. Asquith

toured the country refuting the arguments of Joseph Chamberlain, who

had resigned from the Cabinet to campaign for tariffs against imported

goods. After the Conservative government of Arthur Balfour fell in December 1905 there was some speculation that Asquith and his allies Richard Haldane and Sir Edward Grey would

refuse to serve unless Campbell-Bannerman accepted a peerage, which

would have left Asquith as the real leader in the House of Commons.

However, the plot (called the "Relugas Compact" after the Scottish

lodge where the men met) collapsed when Asquith agreed to serve as Chancellor of the Exchequer under

Campbell-Bannerman (Grey became Foreign Secretary and Haldane Secretary

of State for War). The party won a landslide victory in the 1906 general election. Asquith demonstrated his staunch support of free trade at the Exchequer. He also introduced the first of the so-called Liberal reforms, including the first old age pensions, but was not as successful as his successor David Lloyd George in getting reforms through Parliament as the House of Lords still had a veto over legislation at that stage. Campbell-Bannerman

resigned due to illness on 3 April 1908 (dying at 10 Downing Street

soon afterwards, as he was too sick to move) and Asquith succeeded him

as Prime Minister. The King, Edward VII, was holidaying in Biarritz, and refused to return to London, citing health grounds. Asquith

was forced to travel to Biarritz for the official "kissing of hands" of

the Monarch, the only time a British Prime Minister has formally taken

office on foreign soil.

In

the 1906 election the Liberals won their greatest landslide in history.

In 1908 Asquith became prime minister with a stellar cabinet of leaders

from all factions of the Liberal party. Working with David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill he

passed the "New Liberalism" legislation setting up unemployment

insurance and ending sweatshop conditions; he set the stage for the

welfare state in Britain. In 1908 he introduced old age pensions. The Asquith government became involved in an expensive naval arms race with the German Empire and began an extensive social welfare programme.

The social welfare programme proved controversial, and Asquith's

government faced severe (and sometimes barely legal) resistance from

the Conservative Party. This came to a head in 1909, when David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, produced a deliberately provocative "People's Budget".

Among the most controversial in British history, it systematically

raised taxes on the rich, especially the landowners, to pay for the

welfare programs (and for new battleships). The Conservatives,

determined to stop passage, used their majority in the House of Lords to

reject the bill. The Lords did not traditionally interfere with finance

bills and their actions thus provoked a constitutional crisis, forcing

the country to a general election in January 1910. The election resulted in a hung parliament, with the Liberals having two more seats than the Conservatives, but lacking an overall majority. The Liberals formed a minority government with the support of the Irish Nationalists. At

this point the Lords now allowed the budget — for which the

Liberals had obtained an electoral mandate — to pass, but the

argument had moved on. The radical solution in this situation was to

threaten to have King Edward VII pack

the House of Lords with freshly-minted Liberal peers, who would

override the Lords' veto. With the Conservatives remaining recalcitrant

in spring of 1910 (as the Lords' veto had prevented the Liberals from

granting Irish Home Rule in 1893), Asquith began contemplating such an

option. King Edward VII agreed to do so, after another general

election, but died on 6 May 1910 (so heated had passions become that

Asquith was accused of having "Killed the King" through stress). His

son, King George V,

was reluctant to have his first act in office be the carrying out of

such a drastic attack on the aristocracy and it required all of

Asquith's considerable powers to convince him to make the promise. This

the King finally did before the second election of 1910, in December, although Asquith did not make this promise public at the time. The

Liberals again won, though their majority in the Commons was now

dependent on MPs from Ireland, who had their own price (at the election

the Liberal and Conservative parties were exactly equal in size; by

1914 the Conservative Party was actually larger owing to by-election

victories). Nonetheless, Asquith was able to curb the powers of the

House of Lords through the Parliament Act 1911,

which essentially broke the power of the House of Lords. The Lords

could now delay for two years, but with some exceptions not defeat

outright, a bill passed by the Commons (this would later be reduced

further by the Attlee government in the late 1940s, so the Lords would

be obliged to accept a bill which had been passed three times in the

same parliamentary session, with some exceptions). The price of Irish support in this effort was the Third Irish Home Rule Bill, which Asquith delivered in legislation in 1912. Asquith's efforts over Irish Home Rule nearly provoked a civil war in Ireland over Ulster,

only averted by the outbreak of a European war. Ulster Protestants, who

wanted no part of a semi-independent Ireland, formed armed volunteer

bands. British army officers (the so-called Curragh Mutiny)

threatened to resign rather than move against Ulstermen whom they saw

as loyal British subjects; Asquith was forced to take on the job of

Secretary of State for War himself on the resignation of the incumbent,

Seeley. The legislation for Irish Home Rule was due to come into

effect, allowing for the two-year delay under the Parliament Act, in

1914 - by which time the Cabinet were discussing allowing the six

predominantly Protestant counties of Ulster to opt out of the

arrangement, which was ultimately suspended owing to the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Although

the Liberals had traditionally been peace oriented, the German invasion

of Belgium in violation of treaties angered the nation and raised the

spectre of German control of the entire continent, which was

intolerable. Asquith led the nation to war in alliance with France. The 1839 Treaty of London had

committed Britain to guard Belgium's neutrality in the event of

invasion, and talks with France since 1905 - kept secret even from most

members of the Cabinet - had set up the mechanism for an expeditionary

force to cooperate militarily with France. Asquith and the Cabinet had the King declare war on the German Empire on 4 August 1914. Asquith

headed the Liberal government going into the war. Only two Cabinet

Ministers (John Morley and John Burns) resigned. At first the dominant

figures in the management of the war were Winston Churchill (First Lord of the Admiralty) and Field-Marshal Lord Kitchener, who had taken over the War Office from Asquith himself. However following a Cabinet split on 25 May 1915, caused by the Shell Crisis (or sometimes dubbed 'The Great Shell Shortage') and the failed offensive at the 1915 Battle of Gallipoli, Asquith became head of a new coalition government,

bringing senior figures from the Opposition into the Cabinet. At first

the Coalition was seen as a political masterstroke, as the Conservative

leader Bonar Law was given a relatively minor job (Secretary for the

Colonies), whilst former Conservative leader A.J.Balfour was given the

Admiralty (replacing Churchill). Kitchener, popular with the public, was

stripped of his powers over munitions (given to a new ministry under

Lloyd George) and strategy (given to the Generals Haig and Robertson, a

move which stored up trouble for the future as they were now under

little political control). Critics

increasingly complained about Asquith's lack of vigour over the conduct

of the war. On Whit Monday 1916 Bonar Law travelled to Asquith's

home — the Wharf, at Sutton Courtenay, Berkshire — to discuss

the succession to the job of Secretary of State for War (Kitchener had

just drowned on a trip to Russia — Asquith offered the job to

Bonar Law, who declined as he had already agreed with Lloyd George that

the latter should have the job). Women's Rights activists also turned

against him when he adopted the 'Business as Usual'

policy at the beginning of the war, while the introduction of

conscription was unpopular with mainstream Liberals. Opponents partly

blamed Asquith for a series of political and military disasters,

including the 1916 Battle of the Somme, at which Asquith's son Raymond was killed, and the Easter Rising in Ireland (April 1916). David Lloyd George,

who had become Secretary of State for War but found himself frustrated

by the reduced powers of that role, now campaigned with the support of

the press baron Lord Northcliffe, to be made chairman of a small

committee to manage the war. Asquith at first accepted, on condition

that the committee reported to him daily and that he was allowed to

attend if he chose, but then — furious at a "Times" editorial

which made it clear that he was being sidelined — withdrew his

consent unless he were allowed to chair the committee personally. At

this point Lloyd George resigned, and on 5 December 1916, no longer

enjoying the support of the press or of leading Conservatives, Asquith

himself resigned, declining to serve under any other Prime Minister

(Balfour or Bonar Law having been mooted as potential new leaders of

the coalition), possibly (although his motives are unclear) in the

mistaken belief that nobody else would be able to form a government.

After Bonar Law declined to form a government, citing Asquith's refusal

to serve under him as a reason, Lloyd George became head of the

coalition two days later — in accordance with his recent demands,

heading a much smaller War Cabinet. Asquith,

along with most leading Liberals, refused to serve in the new

government. He remained leader of the Liberal Party after 1916, but

found it hard to conduct an official opposition in wartime. The Liberal

Party finally split openly at The Maurice Debate in 1918, at which Lloyd George was accused (almost certainly correctly)

of hoarding manpower in the UK to prevent Haig from launching any fresh

offensives (eg. Passchendaele, 1917), thus avoiding heavy British

casualties but also contributing to the general Allied weakness during

the resultant successful German offensives of spring 1918. Lloyd George

survived the debate. In

1918 Asquith declined an offer of the job of Lord Chancellor as this

would have meant retiring from active politics in the House of Commons.

By this time Asquith had become very unpopular with the public (as

Lloyd George was perceived to have "won the war" by displacing him)

and, along with most leading Liberals lost his seat in the 1918 elections,

at which the Liberals split into Asquith and Lloyd George factions.

Asquith was not opposed by a Coalition candidate, but the local

Conservative Association eventually put up a candidate against him, who

despite being refused the "Coupon" - the official endorsement given by

Lloyd George and Bonar Law to Coalition candidates - defeated Asquith.

Asquith returned to the House of Commons in a 1920 by-election in Paisley. After

Lloyd George ceased to be Prime Minister in late 1922 the two Liberal

factions enjoyed an uneasy truce, which was deepened in late 1923 when

Stanley Baldwin called an election on the issue of tariffs, which had

been a major cause of the Liberal landslide of 1906. The election

resulted in a hung Parliament, with the Liberals in third place behind

Labour. Asquith played a major role in putting the minority Labour government of January 1924 into office, elevating Ramsay MacDonald to the Prime Ministership. Asquith again lost his seat in the 1924 election held

after the fall of the Labour government — at which the Liberals

were reduced to the status of a minor party with only 40 or so MPs. In

1925 he was raised to the peerage as Viscount Asquith of Morley in the West Riding of the County of York and Earl of Oxford and Asquith.

Lloyd George succeeded him as chairman of the Liberal Members of

Parliament, but Asquith remained head of the party until 1926, when

Lloyd George, who had quarrelled with Asquith once again over whether

or not to support the General Strike (Asquith supported the

government), succeeded him in that position as well. In 1894 Asquith was elected a Bencher of Lincoln's Inn, and in served as Treasurer in 1920. In 1925 Asquith was nominated for the Chancellorship of the University of Oxford, but lost to Viscount Cave in a contest dominated by party political feeling, and despite the support of his former political enemy the Earl of Birkenhead. On 6 November 1925 he was made a Freeman of Huddersfield. Towards

the end of his life Asquith was confined to a wheelchair by a stroke.

He died at his country home The Wharf, Sutton Courtenay, Berkshire in 1928. Margot died in 1945. They are both buried at All Saints' Church, Sutton Courtenay (now in Oxfordshire); Asquith requested that there should be no public funeral. Asquith's estate was probated at £9,345 on 9 June 1928 (about £420 thousand today), a

modest amount for so prominent a man. In the 1880s and 1890s he had

earned a handsome income as a barrister, but in later years had found

it increasingly difficult to sustain his lavish lifestyle, and his

mansion at Cavendish Square had had to be sold in the 1920s. Asquith

had five children by his first wife Helen, and five by his second wife

Margot, but only his elder five children and two of his five younger

children survived birth and infancy. His eldest son Raymond Asquith was killed at the Somme in 1916, and thus the peerage passed to Raymond's only son Julian, now 2nd Earl of Oxford and Asquith (born in 1916, only a few months before his grandfather's resignation as Prime Minister).

His only daughter by his first wife, Violet (later Violet Bonham-Carter), became a well-regarded writer and a life peeress (as Baroness Asquith of Yarnbury in her own right). His fourth son Sir Cyril, Baron Asquith of Bishopstone (1890-1954) became a Law Lord. His second and third sons married well, the poet Herbert Asquith (1881-1947) (who is often confused with his father) married the daughter of an Earl and Brigadier-General Arthur Asquith (1883-1939) married the daughter of a baron. His two children by Margot were Elizabeth (later Princess Antoine Bibesco), a writer, and Anthony Asquith, a film-maker whose productions included The Browning Version and The Winslow Boy. Among his living descendants are his great-granddaughter, the actress Helena Bonham Carter (b. 1966); and his great-grandson, Dominic Asquith, British Ambassador to Egypt since December 2007. Another leading British actress, Anna Chancellor (b. 1965), is also a descendant, being Herbert Asquith's great-great-granddaughter on her mother's side.