<Back to Index>

- Chemist Irène Joliot-Curie, 1897

- Painter and Photographer George Hendrik Breitner, 1857

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Herbert Henry Asquith, 1852

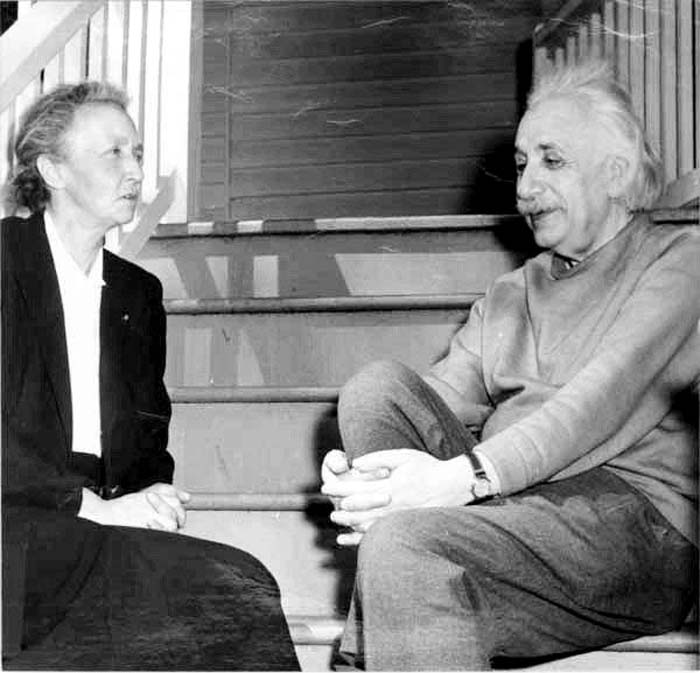

Irène Joliot-Curie (12 September 1897 – 17 March 1956) was a French scientist, the daughter of Marie Skłodowska-Curie and Pierre Curie and the wife of Frédéric Joliot-Curie. Jointly with her husband, Joliot-Curie was awarded the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1935 for their discovery of artificial radioactivity. This made the Curies the family with most Nobel laureates to date. Both children of the Joliot-Curies, Hélène and Pierre, are also esteemed scientists.

Joliot-Curie

was born in Paris. After a year of traditional education, which began

when she was 6 years old, her parents realized her obvious mathematical

talent and decided that Irène’s academic abilities needed a more

challenging environment. Marie joined forces with a number of eminent

French scholars, including the prominent French physicist Paul Langevin to form “The Cooperative,” a private gathering of some of the most distinguished academics in

France. Each contributed to educating one another’s children in their

respective homes. The curriculum of The Cooperative was varied and

included not only the principles of science and scientific research but

such diverse subjects as Chinese and sculpture and with great emphasis

placed on self expression and play. This arrangement lasted for two years after which Joliot-Curie re-entered a more orthodox learning environment at the Collège Sévigné in central Paris from 1912 to 1914 and then onto the Faculty of Science at the Sorbonne, to complete her Baccalaureat. Her studies at the Faculty of Science were interrupted by World War I. Initially, Joliot-Curie was taken by her mother to Brittany,

but a year later when she turned 18 she was re-united with her mother,

running the 20 mobile field hospitals that Marie had established. The

hospitals were equipped with primitive X-ray equipment made possible by

the Curies’ radiochemical research. This technology greatly assisted

doctors to locate shrapnel in wounded soldiers, but it was crude and

led to both Marie and Irène, who were serving as nurse

radiographers, to suffer large doses of radiation exposure. After

the War, Joliot-Curie returned to Paris to study at The Radium

Institute, which had been built by her parents. The institute was

completed in 1914 but remained empty during the war. Her doctoral

thesis was concerned with the alpha rays of polonium,

the second element discovered by her parents and named after Marie’s

country of birth, Poland. Joliot-Curie became Doctor of Science in 1925. As

she neared the end of her doctorate in 1924 she was asked to teach the

precise laboratory techniques required for radiochemical research to

the young chemical engineer Frédéric Joliot who she would later come to wed. From

1928 Joliot-Curie and husband Frédéric combined their

research interests on the study of atomic nuclei. Though their

experiments identified both the positron and the neutron, they failed

to interpret the significance of the results and the discoveries were

later claimed by C.D. Anderson and James Chadwick respectively. These

discoveries would have secured greatness indeed, as together with J.J. Thomson's discovery of the electron in 1897, they finally replaced Dalton’s theory of atoms being solid spherical particles. Finally,

in 1934 they made the discovery that sealed their place in scientific

history. Building on the work of Marie and Pierre, who had isolated

naturally occurring radioactive elements, Joliot-Curies realised the

alchemist’s dream of turning one element into another, creating

radioactive nitrogen from boron and then radioactive isotopes of phosphorus from aluminium and silicon from magnesium. For example irradiating the main natural and stable isotope of aluminum with alpha particles (i.e. helium nuclei) results in an unstable isotope of phosphorus : 27Al + 4He > 30P + 1n.

By now the application of radioactive materials for use in medicine was

growing and this discovery led to an ability to create radioactive

materials quickly, cheaply and plentifully. The Nobel Prize for

chemistry in 1935 brought with it fame and recognition from the

scientific community and Joliot-Curie was awarded a professorship at

the Faculty of Science. Irène’s

group pioneered research into radium nuclei that led a separate group

of German physicists to discover nuclear fission; the splitting of the

nucleus itself and the vast amounts of energy emitted as a result. The years of working so closely with such deadly materials finally caught up with Joliot-Curie and she was diagnosed with leukemia. She had been accidentally exposed to polonium when

a sealed capsule of the element exploded on her laboratory bench in

1946. Treatment with antibiotics and a series of operations did relieve

her suffering temporarily but her condition continued to deteriorate.

Despite this Joliot-Curie continued to work and in 1955 drew up plans

for new physics laboratories at the Universitie d’Orsay, South of Paris. The

Joliot-Curies had become increasingly aware of the growth of the

fascist movement. They opposed its ideals and joined the Socialist Party in 1934, the Comité de Vigilance des Intellectuels Antifascistes a year later, and in 1936 actively supported the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War.

In the same year, Joliot-Curie was appointed Undersecretary of State

for Scientific Research for the French government where she helped in

founding the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. The

Joliot-Curies had continued Pierre and Marie’s policy of publishing all

of their work for the benefit of the global scientific community, but

afraid of the danger that might result should it be developed for

military use, they stopped. On 30 October 1939 they placed all of their

documentation on nuclear fission in the vaults of the Académie

des Sciences where it remained until 1949. Joliot-Curie's

political career continued after the war and she became a commissioner

in the Commissariat à l'énergie Atomique. However, she

still found time for scientific work and in 1946 became director of her

mother’s Institut du Radium, Radium Institute. Joliot-Curie

became actively involved in promoting women’s education, serving on the

National Committee of the Union of French Women (Comité National de l'Union des Femmes Françaises) and the World Peace Council. Joliot-Curies were given memberships to the French Légion d'honneur; Irène as an officer and Frederic as a commissioner, recognising his earlier work for the resistance. Irène

and Frédéric hyphenated their surnames to Joliot-Curie

after they married 1926. Eleven months later, their daughter Hélène was born, who would also become a noted physicist. Their son, Pierre, a biologist, was born in 1932. During World War II Joliot-Curie

contracted tuberculosis and was forced to spend the next few years

convalescing in Switzerland. Concern for her own health together with

the anguish of leaving her husband and children in occupied France was

hard to bear and she did make several dangerous visits back to France,

enduring detention by German troops at the Swiss border on more than

one occasion. Finally, in 1944 Joliot-Curie judged it too dangerous for

her family to remain in France and she took her children back to

Switzerland. In

1956, after a final convalescent period in the French Alps,

Joliot-Curie was admitted to the Curie hospital in Paris where she died

on 17 March at the age of 58 from leukemia. Joliot-Curie's daughter, Hélène Langevin-Joliot, is a nuclear physicist and professor at the University of Paris; her son, Pierre Joliot, is a biochemist at Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.