<Back to Index>

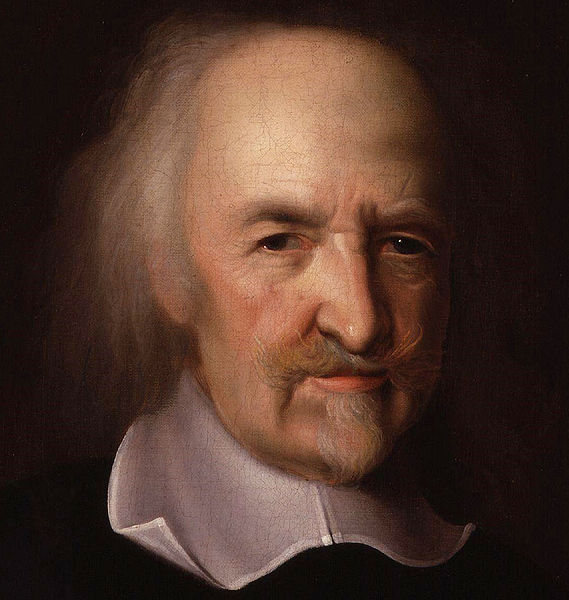

- Philosopher Thomas Hobbes, 1588

- Composer Louis Spohr, 1784

- Prime Minister of France Jules François Camille Ferry, 1832

PAGE SPONSOR

Thomas Hobbes (5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679), in some older texts Thomas Hobbs of Malmsbury, was an English philosopher, remembered today for his work on political philosophy. His 1651 book Leviathan established the foundation for most of Western political philosophy from the perspective of social contract theory.

Hobbes

was a champion of absolutism for the sovereign but he also developed

some of the fundamentals of European liberal thought: the right of the

individual; the natural equality of all men; the artificial character

of the political order (which led to the later distinction between civil

society and the

state); the view that all legitimate political power must be

"representative" and based on the consent of the people; and a liberal

interpretation of law which leaves people free to do whatever the law

does not explicitly forbid. Hobbes

also contributed to a diverse array of fields, including history, geometry,

physics

of gases, theology, ethics,

general philosophy,

and political

science. His account of human nature as self-interested cooperation

has proved to be an enduring theory in the field of philosophical

anthropology. He was one of the main philosophers who founded materialism. Thomas

Hobbes was born in Wiltshire, England on 5 April 1588, some

sources say at Malmesbury.

Born

prematurely when his mother heard of the coming invasion of the Spanish

Armada, Hobbes later reported that "my mother gave birth to twins:

myself and fear." His childhood is almost a

complete blank, and his mother's name is unknown. His father, also named

Thomas, was the vicar of Charlton and Westport.

Thomas

Sr. abandoned his three children to the care of an older

brother, Thomas junior's uncle Francis, when he was forced to flee to

London after being involved in a fight with a clergyman outside his own

church. Hobbes was educated at Westport church from the age of four,

passed to the Malmesbury

school and then to

a private school kept by a young man named Robert Latimer, a graduate

of the University

of

Oxford. Hobbes was a good pupil, and around 1603 he went up to

Magdalen Hall, which is most closely related to Hertford

College,

Oxford. The principal John

Wilkinson was a Puritan,

and

he had some influence on Hobbes. At

university, Hobbes appears to have followed his own curriculum; he was

"little attracted by the scholastic learning". He did not complete his B.A. degree until 1608, but he

was recommended by Sir James Hussey, his master at Magdalen, as tutor

to William, the son of William

Cavendish, Baron of Hardwick (and later Earl

of

Devonshire), and began a life-long connection with that family. Hobbes

became a companion to the younger William and they both took part in a grand

tour in 1610.

Hobbes was exposed to European scientific and critical methods during

the tour in contrast to the scholastic

philosophy which he

had learned in Oxford. His scholarly efforts at the time were aimed at

a careful study of classic Greek and Latin authors, the outcome of

which was, in 1628, his great translation of Thucydides' History

of

the Peloponnesian War, the first translation of that work

into English from a Greek manuscript. Although

he associated with literary figures like Ben

Jonson and thinkers

such as Francis

Bacon, he did not extend his efforts into philosophy until after

1629. His employer Cavendish, then the Earl of Devonshire, died of the plague in

June 1628. The widowed

countess dismissed Hobbes but he soon found work, again as a tutor,

this time to the son of Sir Gervase Clifton. This task, chiefly spent

in Paris, ended in 1631 when he again found work with the Cavendish

family, tutoring the son of his previous pupil. Over the next seven

years as well as tutoring he expanded his own knowledge of philosophy,

awakening in him curiosity over key philosophic debates. He visited Florence in 1636 and later was a

regular debater in philosophic groups in Paris, held together by Marin

Mersenne. From 1637 he considered himself a philosopher and scholar. Hobbes's

first area of study was an interest in the physical doctrine of motion

and physical momentum. Despite his interest in this phenomenon, he

disdained experimental work as in physics.

He

went on to conceive the system of thought to the elaboration of

which he would devote his life. His scheme was first to work out, in a

separate treatise, a systematic doctrine of body, showing how physical

phenomena were universally explicable in terms of motion, at least as

motion or mechanical action was then understood. He then singled out

Man from the realm of Nature and plants. Then, in another treatise, he

showed what specific bodily motions were involved in the production of

the peculiar phenomena of sensation, knowledge, affections and passions

whereby Man came into relation with Man. Finally he considered, in his

crowning treatise, how Men were moved to enter into society, and argued

how this must be regulated if Men were not to fall back into

"brutishness and misery". Thus he proposed to unite the separate

phenomena of Body, Man, and the State. Hobbes

came home, in 1637, to a country riven with discontent which disrupted

him from the orderly execution of his philosophic plan. However, by the

end of the Short

Parliament in 1640,

he had written a short treatise called The Elements of Law,

Natural and Politic. It was not published and only circulated among

his acquaintances in manuscript form. A pirated version, however, was

published about ten years later. Although it seems that much of The Elements of Law was composed before the

sitting of the Short

Parliament, there are polemical pieces of the work that clearly

mark the influences of the rising political crisis. Nevertheless, many

(though not all) elements of Hobbes's political thought were unchanged

between The Elements

of Law and Leviathan, which demonstrates that the

events of the English

Civil

War had

little effect on his contractarian methodology. It should be noted,

however, that the arguments in Leviathan were modified fromThe

Elements of Law when

it

came to the necessity of consent in creating political obligation.

Namely, Hobbes wrote in The

Elements

of Law that

Patrimonial kingdoms were not necessarily formed by the consent of the

governed, while in Leviathan he argued that they were.

This was perhaps a reflection either of Hobbes's thoughts concerning the engagement

controversy or of

his reaction to treatises published by Patriarchalists,

such

as Sir

Robert

Filmer, between 1640 and 1651. When in

November 1640 the Long

Parliament succeeded

the

Short, Hobbes felt he was a marked man by the circulation of his

treatise and fled to Paris. He did not return for eleven years. In

Paris he rejoined the coterie about Mersenne, and wrote a critique of

the Meditations on

First Philosophy of Descartes,

which

was printed as third among the sets of "Objections" appended,

with "Replies" from Descartes in 1641. A different set of remarks on

other works by Descartes succeeded only in ending all correspondence

between the two. Hobbes

also extended his own works somewhat, working on the third section, De

Cive, which was finished in November 1641. Although it was

initially only circulated privately, it was well received, and included

lines of argumentation to be repeated a decade later in the Leviathan.

He

then returned to hard work on the first two sections of his work and

published little except for a short treatise on optics (Tractatus

opticus) included in the collection of scientific tracts published

by Mersenne as Cogitata

physico-mathematica in

1644. He built a good reputation in philosophic circles and in 1645 was

chosen with Descartes, Gilles

de

Roberval and

others, to referee the controversy between John

Pell and Longomontanus over the problem of squaring

the

circle. The English

Civil

War broke out

in 1642, and when the Royalist cause began to decline in

the middle of 1644 there was an exodus of the king's supporters to

Europe. Many came to Paris and were known to Hobbes. This revitalised

Hobbes's political interests and the De Cive was republished and more widely distributed. The printing began

in 1646 by Samuel

de

Sorbiere through

the Elsevier

press at Amsterdam with

a

new preface and some new notes in reply to objections. In 1647,

Hobbes was engaged as mathematical instructor to the young Charles,

Prince

of Wales, who had come over from Jersey around July.

This engagement lasted until 1648 when Charles went to Holland. The

company of the exiled royalists led Hobbes to produce an English book

to set forth his theory of civil government in relation to the

political crisis resulting from the war. The State, it now seemed to

Hobbes, might be regarded as a great artificial man or monster (Leviathan), composed

of men, with a life that might be traced from its generation

under pressure of human needs to its dissolution through civil strife

proceeding from human passions. The work was closed with a general

"Review and Conclusion", in direct response to the war which raised the

question of the subject's right to change allegiance when a former

sovereign's power to protect was irrecoverably gone. Also he criticized

religious doctrines on rationalistic grounds in the Commonwealth. During

the years of the composition of Leviathan he remained in or near

Paris. In 1647 Hobbes was overtaken by a serious illness which disabled

him for six months. On recovering from this near fatal disorder, he

resumed his literary task, and carried it steadily forward to

completion by the year 1650. Meanwhile, a translation of De Cive was being produced; there

has been much scholarly disagreement over whether Hobbes translated the

work himself or not. In 1650,

a pirated edition of The

Elements

of Law, Natural and Politic was

published. It was

divided into two separate small volumes (Human Nature, or the

Fundamental Elements of Policie and De corpore politico, or

the Elements of Law, Moral and Politick). In 1651 the translation of De

Cive was

published under the title of Philosophicall

Rudiments

concerning Government and Society. Meanwhile, the printing of the greater work was proceeding, and finally it appeared

about the middle of 1651, under the title of Leviathan,

or

the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Common Wealth, Ecclesiasticall and

Civil, with a famous title-page engraving in which, from behind

hills overlooking a landscape, there towered the body (above the waist)

of a crowned giant, made up of tiny figures of human beings and bearing sword and crozier in the two hands. The work

had immediate impact. Soon Hobbes was more lauded and decried than any

other thinker of his time. However, the first effect of its publication

was to sever his link with the exiled royalists, forcing him to appeal

to the revolutionary English government for protection. The exiles

might very well have killed him; the secularist spirit of his book

greatly angered both Anglicans and French Catholics. Hobbes fled back

home, arriving in London in the winter of 1651. Following his

submission to the council of state he was allowed to subside into

private life in Fetter

Lane. In Leviathan,

Hobbes

set out his doctrine of the foundation of states and legitimate governments - based on social

contract

theories. Leviathan was written during the English

Civil

War; much of the book is occupied with demonstrating the

necessity of a strong central authority to avoid the evil of discord

and civil war. Beginning

from a mechanistic understanding of human

beings and the passions, Hobbes postulates what life would be like

without government, a condition which he calls the state

of

nature. In that state, each person would have a right, or

license, to everything in the world. This, Hobbes argues, would lead to

a "war of all against all" (bellum

omnium

contra omnes), and thus lives that are "solitary, poor,

nasty, brutish, and short". To escape

this state of war, men in the state of nature accede to a social

contract and

establish a civil

society. According to Hobbes, society is a population beneath a sovereign authority,

to whom all individuals in that society cede their natural rights for

the sake of protection. Any abuses of power by this authority are to be

accepted as the price of peace. However, he also states that in severe

cases of abuse, rebellion is expected. In particular, the doctrine of separation

of

powers is

rejected: the sovereign must control

civil, military, judicial and ecclesiastical powers. Leviathan was also well-known for its

radical religious views, which were often Hobbes's attempt to

reinterpret scripture from his materialist assumptions. His denial of

incorporeal entities led him to write, for example, that Heaven and Hell were places on Earth, and to take other positions out of sync with church teachings of his time.

Much has been made of his religious views by scholars such as Richard

Tuck and J.G.A. Pocock, but there is still widespread disagreement about the

significance of Leviathan's

contents

concerning religion. Many have taken the work to mean that

Hobbes was an atheist, while others find the evidence for this position

insufficient.

Hobbes

now

turned to complete the fundamental treatise of his philosophical

system. He worked so steadily that De

Corpore was first

printed in 1654. Also in 1654, a small treatise, Of Liberty and Necessity,

was

published by Bishop John

Bramhall, addressed at Hobbes. Bramhall, a strong Arminian,

had

met and debated with Hobbes and afterwards wrote down his views and

sent them privately to be answered in this form by Hobbes. Hobbes duly

replied, but not for publication. But a French acquaintance took a copy

of the reply and published it with "an extravagantly laudatory

epistle." Bramhall countered in 1655, when he printed everything that

had passed between them (under the title of A Defence of the True

Liberty of Human Actions from Antecedent or Extrinsic Necessity).

In 1656 Hobbes was ready with The

Questions

concerning Liberty, Necessity and Chance, in which he

replied "with astonishing force" to the bishop. As perhaps the first

clear exposition of the psychological doctrine of determinism, Hobbes's

own two pieces were important in the history of the free-will controversy. The bishop

returned to the charge in 1658 with Castigations

of

Mr Hobbes's Animadversions, and also included a bulky appendix

entitled The

Catching of Leviathan the Great Whale. Hobbes never took any notice

of the Castigations.

Beyond

the

spat with Bramhall, Hobbes was caught in a series of conflicts from

the time of publishing his De

Corpore in

1655. In Leviathan he

had

assailed the system of the original universities. Because Hobbes

was so evidently opposed to the existing academic arrangements, and

because De Corpore contained not only

tendentious views on mathematics, but an unacceptable proof of the squaring of

the circle (which

was apparently an afterthought), mathematicians took him to be a target

for polemics. John

Wallis was not the

first such opponent, but he tenaciously pursued Hobbes. The resulting

controversy continued well into the 1670s. Hobbes

published, in 1658, the final section of his philosophical system,

completing the scheme he had planned more than twenty years before. De

Homine consisted

for

the most part of an elaborate theory of vision. The remainder of

the treatise dealt cursorily with some of the topics more fully treated

in the Human Nature and the Leviathan. In

addition to publishing some controversial writings on mathematics and

physics, Hobbes also continued to produce philosophical works. From the

time of the Restoration he acquired a new

prominence; "Hobbism" became a byword for all that respectable society

ought to denounce. The young king, Hobbes's former pupil, now Charles

II, remembered Hobbes and called him to the court to grant him a

pension of £100. The king

was important in protecting Hobbes when, in 1666, the House

of

Commons introduced

a bill against atheism and profaneness. That same year, on 17 October

1666, it was ordered that the committee to which the bill was referred

"should be empowered to receive information touching such books as tend

to atheism, blasphemy and profaneness... in particular... the book of

Mr. Hobbes called the Leviathan". Hobbes was terrified at the

prospect of being labelled a heretic, and proceeded to burn some of his

compromising papers. At the same time, he examined the actual state of

the law of heresy.

The

results of his investigation were first announced in three short

Dialogues added as an Appendix to his Latin translation of

Leviathan, published at Amsterdam in 1668. In this appendix, Hobbes

aimed to show that, since the High

Court

of Commission had

been put down, there remained no court of heresy at all to which he was

amenable, and that nothing could be heresy except opposing the Nicene

Creed, which, he maintained, Leviathan did not do. The only

consequence that came of the bill was that Hobbes could never

thereafter publish anything in England on subjects relating to human

conduct. The 1668 edition of his works was printed in Amsterdam because

he could not obtain the censor's licence for its publication in

England. Other writings were not made public until after his death,

including Behemoth:

the History of the Causes of the Civil Wars of England and of the

Counsels and Artifices by which they were carried on from the year 1640

to the year 1662. For some time, Hobbes was not even allowed to

respond, whatever his enemies tried. Despite this, his reputation

abroad was formidable, and noble or learned foreigners who came to

England never forgot to pay their respects to the old philosopher. His final

works were a curious mixture: an autobiography in Latin verse in 1672,

and a translation of four books of the Odyssey into "rugged" English

rhymes that in 1673 led to a complete translation of both Iliad and Odyssey in 1675. In

October 1679, Hobbes suffered a bladder disorder, which was followed by

a paralytic stroke from which he died on 4 December 1679. He is said to

have uttered the last words "A great leap in the dark" in his final

moments of life. He was interred within St.

John the Baptist Church in Ault

Hucknall in Derbyshire, England.