<Back to Index>

- Inventor Samuel Finley Breese Morse, 1791

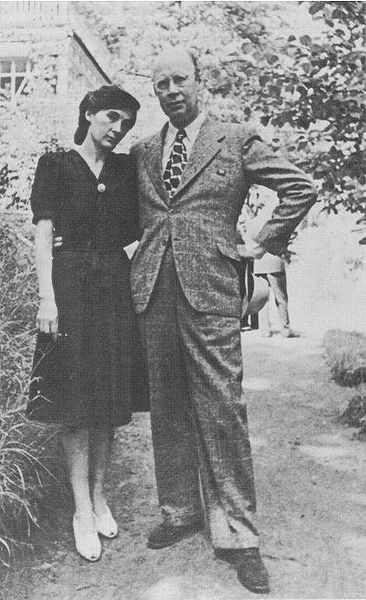

- Composer Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev, 1891

- Queen Consort of Spain Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies, 1806

PAGE SPONSOR

Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev (Russian: Серге́й Серге́евич Проко́фьев) (27 April [O.S. 15 April] 1891 – 5 March 1953) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor who mastered numerous musical genres and came to be admired as one of the greatest composers of the 20th century.

Prokofiev

was born in Sontsovka (now Krasne in Donetsk

oblast, Ukraine),

an

isolated rural estate in Yekaterinoslav

Governorate, Russian Empire. He displayed unusual musical abilities by the age of five.

His first piano composition to be written down (by his mother), an

'Indian Gallop', was in the Lydian

mode (F major with

a B natural instead of B flat) as the young Prokofiev felt 'reluctance

to tackle the black notes'. By the age of seven he had

also learned to play chess. Much like music, chess

would remain a passion his entire life, and he became acquainted with

world chess champions José

Raúl

Capablanca and Mikhail

Botvinnik. At the

age of nine he was composing his first opera, The

Giant, as well as an overture and

miscellaneous pieces. In 1902,

Prokofiev's mother met with Sergei

Taneyev, director of the Moscow

Conservatory, who initially suggested that Prokofiev should start

lessons in composition with Alexander

Goldenweiser. When Taneyev was unable to

arrange this, he

instead

arranged for Reinhold Glière to

spend the summer of 1902 in Sontsovka teaching Prokofiev. This first series of

lessons culminated, at Prokofiev's insistence, with the 11-year-old

making his first attempt to write a symphony under Glière's

supervision. Glière subsequently

revisited Sontsovka the following summer to give further tuition. When decades later

Prokofiev wrote in his autobiography about his lessons with

Glière, he gave due credit to Glière's sympathetic

qualities as a teacher but complained that Glière had introduced

him to "square" phrase structure and conventional modulations which he

subsequently had to unlearn. Nonetheless, now equipped

with the necessary theoretical tools, Prokofiev started experimenting

with dissonant harmonies and unusual time signatures in a series of

short piano pieces which he called "ditties" (after the so-called "song

form" - more accurately ternary

form - they were

based on), laying the basis for his own musical style. After a

while, Prokofiev's mother felt that the isolation in Sontsovka was

restricting his further musical development, yet his parents hesitated over starting their son on a musical career at such an early age. Then in 1904, while

Prokofiev was in Saint

Petersburg with his mother exploring the prospect of their moving there for his education, they were introduced to the

composer Alexander

Glazunov, a professor at the Conservatory. Glazunov agreed to see

Prokofiev and his music, and was so impressed that he urged Prokofiev's

mother that her son should apply to the Saint

Petersburg

Conservatory. By this point Prokofiev had

composed two more operas, Desert

Islands and The Feast during the

Plague and was

working on his fourth, Undine. He passed the introductory

tests and entered the Conservatory that same year. Being

several years younger than most of his classmates, he was viewed as

eccentric and arrogant, and he often expressed dissatisfaction with

much of the education, which he found boring. During this period he

studied under, among others, Anatoly

Lyadov, Nikolai Tcherepnin and Nikolai

Rimsky-Korsakov (though

when

the latter died in 1908, Prokofiev noted that he had only studied

orchestration with him 'after a fashion' – that is, in a heavily

attended class with other students – and regretted he otherwise 'never

had the opportunity to study with him'). He also became friends with

composers Boris

Asafyev and Nikolai

Myaskovsky. As a

member of the Saint Petersburg music scene, Prokofiev expanded his

reputation as a musical rebel, while also getting praise for his

original compositions, which he would perform himself on the piano. In

1909, he graduated from his class in composition, getting less than

impressive marks. He continued at the Conservatory, studying piano under Anna

Yesipova and conducting under Nikolai

Tcherepnin. In 1910,

Prokofiev's father died and Sergei's financial support ceased. Luckily,

at that time, he had started making a name for himself as a composer,

although he frequently caused scandals with his forward-looking works. The Sarcasms for piano, Op. 17 (1912),

for example, make extensive use of polytonality, and Etudes, Op. 2 (1909)

and Four Pieces, Op. 4 (1908) are highly chromatic and dissonant works.

His first two piano

concertos were

composed around this time, the latter of which caused a scandal at its

premiere (23 August 1913, Pavlovsk). According to one account, the

audience left the hall with exclamations of "'To hell with this

futuristic music! The cats on the roof make better music!'", but the

modernists were in raptures. In 1911

help arrived from renowned Russian musicologist and critic Alexander

Ossovsky, who wrote a letter in strong support of Sergei Prokofiev to famous music publisher Boris P. Jurgenson,

thus

a contract was offered to the composer. Prokofiev

made

his first excursion out of Russia in 1913, travelling to Paris and

London where he first encountered Sergei

Diaghilev's Ballets

Russes.

In

1914,

Prokofiev finished his career at the Conservatory by entering the

so-called 'battle of the pianos', a competition open to the five best

piano students for which the prize was a Schreder grand piano:

Prokofiev won by performing his own Piano

Concerto

No. 1. Soon afterwards, he made a

trip to London where he made contact with the impresario Diaghilev.

Diaghilev commissioned Prokofiev's first ballet, Ala and Lolli, but

rejected the work in progress when Prokofiev brought it to him in Italy

in 1915; however Diaghilev then commissioned Prokofiev to compose the

ballet Chout.

Under

Diaghilev's guidance, Prokofiev chose his subject from a

collection of folktales by the ethnographer Alexander

Afanasyev;

the

story, concerning a buffoon and a series of confidence tricks he

performs, had been previously suggested to Diaghilev by Igor

Stravinsky as a

possible subject for a ballet, and Diaghilev and his choreographer Léonide Massine helped

Prokofiev to shape this into a ballet scenario. Prokofiev's relative lack

of experience in ballet composing meant he subsequently agreed to

revise the ballet extensively in the 1920s, following Diaghilev's

detailed critique of the score,

prior

to its first production. The

ballet's

premiere in Paris on 17 May 1921 was a huge success and was

greeted with great admiration by an audience that included Jean

Cocteau, Igor

Stravinsky and Maurice

Ravel. Stravinsky called the ballet "the single piece of modern

music he could listen to with pleasure," while Ravel called it "a work

of genius."

During World

War

I, Prokofiev returned again to the Conservatory, now studying

the organ in order to avoid conscription.

He

composed his opera The

Gambler based on Fyodor

Dostoyevsky's novel

of

the same name, but the rehearsals were plagued by problems and

the première scheduled for 1917 had to be cancelled because of

the February

Revolution. In the summer of that same year, Prokofiev composed his first

symphony, the Classical.

This

was his own name for the symphony, which was written in the style

that, according to Prokofiev, Joseph

Haydn would have

used if he had been alive at the time. Hence, the symphony is more

or less classical in style but incorporates more modern musical

elements (Neoclassicism).

This

symphony was also an exact contemporary of Prokofiev's Violin

Concerto No. 1 in D major, Op. 19, which was scheduled to premiere

in November 1917. Political events, however, delayed the first

performances of both works until 21 April 1918 and 18 October 1923,

respectively. After a brief stay with his mother in Kislovodsk in the Caucasus, because of

worries of the enemy capturing Petrograd (the new name for Saint

Petersburg), he returned in 1918, but he was now determined to leave

Russia, at least temporarily. In the current Russian

state of unrest, he saw no room for his experimental music and, in May,

he headed for the USA.

Despite

this, he had already developed acquaintances with senior Bolsheviks including Anatoly

Lunacharsky, the People's Commissar for Education, who told him:

"You are a revolutionary in music, we are revolutionaries in life. We

ought to work together. But if you want to go to America I shall not

stand in your way." Arriving

in San

Francisco, after having been released from questioning by

immigration on Angel Island on 11 August 1918, Prokofiev was soon compared

to other famous Russian exiles (such as Sergei

Rachmaninoff), and he started out successfully with a solo concert in New York, leading to several further engagements. He also received a

contract for the production of his new opera The

Love

for Three Oranges but,

due

to illness and the death of the director, the premiere was

postponed. This was another example of Prokofiev's bad luck in operatic

matters. The failure also cost him his American solo career, since the

opera took too much time and effort. He soon found himself in financial

difficulties, and, in April 1920, he left for Paris,

not

wanting to return to Russia as a failure. Paris was

better prepared for Prokofiev's musical style. He reaffirmed his

contacts with the Diaghilev's Ballets

Russes. He also returned to some of his older, unfinished works,

such as the Third

Piano

Concerto. The

Love for Three Oranges finally

premièred

in Chicago in December 1921, under the

composer's baton. In March

1922, Prokofiev moved with his mother to the town of Ettal in the Bavarian Alps

for

over a year so he could concentrate fully on his composing. Most of

his time was spent on an opera project, The

Fiery

Angel, based on the novel The

Fiery

Angel by Valery

Bryusov. By this time his later music had acquired a certain

following in Russia, and he received invitations to return there, but

he decided to stay in Europe. In 1923, he married the Spanish singer

Lina Llubera (1897 – 1989), before moving back to Paris. There,

several of his works (for example the Second

Symphony) were performed, but critical reception was lukewarm. However

the

Symphony appeared to prompt Diaghilev to commission another ballet

from Prokofiev: this was Le

Pas

d'acier (The Steel Step), a 'modernist' score intended to

portray the industrialisation of the Soviet Union. This was

enthusiastically received by Parisian audiences and critics. Prokofiev

and Stravinsky restored their friendship, though Prokofiev did not

particularly like Stravinsky's later works;

it

has been suggested that his use of text from Stravinsky's A

Symphony

of Psalms to

characterise the invading Teutonic knights in the film score for Eisenstein's Alexander

Nevsky (1938)

was intended as an attack on Stravinsky's musical idiom. However,

Stravinsky

himself described Prokofiev as the greatest Russian composer

of his day, other than Stravinsky himself. Around

1927, the virtuoso's situation brightened; he had some exciting

commissions from Diaghilev and made a number of concert tours in

Russia; in addition, he enjoyed a very successful staging of The Love for Three

Oranges in

Leningrad (as Saint Petersburg was then known). Two older operas (one

of them The Gambler)

were

also played in Europe and in 1928 Prokofiev produced his Third

Symphony, which was broadly based on his unperformed opera The Fiery Angel. The

conductor Sergei

Koussevitzky characterized

the

Third as "the greatest symphony since Tchaikovsky's Sixth." During

1928–29 Prokofiev composed what was to be the last ballet for Diaghilev, The

Prodigal

Son, which was staged on 21 May 1929 in Paris with Serge

Lifar in the title

role. Diaghilev died only months

later. In 1929,

Prokofiev wrote the Divertimento,

Op.

43 and revised his Sinfonietta,

Op.

5/48, a work started in his days at the Conservatory. Prokofiev wrote

in his autobiography that he could never understand why the

Sinfonietta was so rarely performed, whereas the "Classical" Symphony

was played everywhere. Later in this year, however, he suffered a car

accident, which slightly injured his hands and prevented him from

performing in Moscow, but in turn permitted him to enjoy contemporary

Russian music. After his hands healed, he made a new attempt at touring

in the United States, and this time he was received very warmly,

propped up by his recent success in Europe. This, in turn, propelled

him to commence a major tour through Europe. In 1930

Prokofiev began his first non-Diaghilev ballet On

the

Dnieper, Op. 51, a work commissioned by Serge Lifar, who

had been appointed maitre

de

ballet at the

Paris Opéra. The years 1931 and 1932 saw

the completion of Prokofiev's fourth and fifth piano concertos. The

following year saw the completion of the Symphonic

Song, Op. 57, a darkly scored piece in one movement. In the

early 1930s, Prokofiev was starting to long for Russia again; he moved more and more of

his premieres and commissions to his home country instead of Paris. One

such was Lieutenant

Kijé, which was commissioned as the score to a Soviet

film. Another commission, from the Kirov

Theater in

Leningrad, was the ballet Romeo

and

Juliet. Today, this is one of Prokofiev's best-known works,

and it contains some of the most inspired and poignant passages in his

whole output. However,

there

were numerous problems related to the ballet's original 'happy

end' (contrary to Shakespeare),

and

the premiere was postponed for several years. In 1935,

Prokofiev moved back to the Soviet Union permanently; his family came a

year later. At this time, the official Soviet policy towards music

changed; a special bureau, the "Composers' Union", was established in

order to keep track of the artists and their doings. By limiting

outside influences, these policies would gradually cause almost

complete isolation of Soviet composers from the rest of the world. Both

Prokofiev and Shostakovich came

under particular

scrutiny for "formalist tendencies." Forced to adapt to the new

circumstances (whatever misgivings he had about them in private),

Prokofiev wrote a series of "mass songs" (Opp. 66, 79, 89), using the

lyrics of officially approved Soviet poets. At the same time Prokofiev

also composed music for children (Three Songs for Children and Peter

and

the Wolf, among others) as well as the gigantic Cantata for the

Twentieth Anniversary of the October Revolution, which was banned from

performance and had to wait until May 1966 for a partial premiere. In 1938,

Prokofiev collaborated with the Russian filmmaker Sergei

Eisenstein on the

historical epic Alexander

Nevsky. For this he composed some of his most inventive

dramatic music. Although the film had a very poor sound recording,

Prokofiev adapted much of his score into a cantata, which has been

extensively performed and recorded. In the wake of Alexander Nevsky's

success, Prokofiev composed his first Soviet opera Semyon

Kotko, which was intended to be produced by the director Vsevolod

Meyerhold. However the première of the opera was postponed

because Meyerhold was arrested on 20 June 1939 by the NKVD (Stalin's

Secret Police), and shot on 2 February 1940. Only months after

Meyerhold's arrest, Prokofiev was 'invited' to compose Zdravitsa (literally translated

'Cheers!', but more often given the English title Hail to Stalin) (Op.

85) to celebrate Joseph

Stalin's 60th birthday. Later in

1939, Prokofiev composed his Piano Sonatas Nos. 6, 7, and 8, Opp.

82–84, widely known today as the "War Sonatas." Premiered respectively

by Prokofiev (No. 6: 8 April 1940), Sviatoslav

Richter (No. 7:

Moscow, 18 January 1943) and Emil

Gilels (No. 8:

Moscow, 30 December 1944),

they

were subsequently championed in particular by Richter. These

sonatas contain some of Prokofiev's most dissonant music for the piano.

Biographer Daniel Jaffé has argued that Prokofiev, "having

forced himself to compose a cheerful evocation of the nirvana Stalin

wanted everyone to believe he had created" (i.e. in Zdravitsa) then

subsequently, in these three sonatas, "expressed his true feelings". As evidence of this,

Jaffé has pointed out that the central movement of Sonata No. 7

opens with a theme based on a Robert

Schumann Lieder,

'Wehmut' ('Sadness', which appears in Schumann's Liederkreis,

Op.

39): the words to this translate "I can sometimes sing as if I

were glad, yet secretly tears well and so free my heart.

Nightingales... sing their song of longing from their dungeon's

depth... everyone delights, yet no one feels the pain, the deep sorrow

in the song." Ironically (though probably

because, it appears, no one had noticed this musical allusion) Sonata

No. 7 received a Stalin Prize (Second Class), and No. 8 a Stalin Prize First Class,

even

though the works have been subsequently interpreted as

representing Prokofiev "venting his anger and frustration with the

Soviet regime." Prokofiev

had been considering making an opera out of Leo

Tolstoy's epic novel War

and

Peace, when news of the German invasion of Russia on 22

June 1941 made the subject seem all the more timely. Prokofiev took two

years to compose his original version of War

and Peace. Because of the war he was evacuated together with a

large number of other artists, initially to the Caucasus where he composed his

Second String Quartet. By this time his relationship with the

25-year-old writer Mira

Mendelson (1915 – 1968)

had

finally led to his separation from his wife Lina, although they

were never technically divorced: indeed Prokofiev had tried to persuade

Lina and their sons to accompany him as evacuees out of Moscow, but

Lina opted to stay in Moscow. During

the war years, restrictions on style and the demand that composers

should write in a 'socialist realist' style were slackened, and

Prokofiev was generally able to compose dissonant and chromatic works.

The Violin

Sonata

No. 1, Op. 80, The Year 1941, Op. 90, and the Ballade for the Boy Who

Remained Unknown, Op. 93, all came from this period. Some critics

have said that the emotional springboard of the First Violin Sonata and

many other of Prokofiev's compositions of this time "may have more to

do with anti-Stalinism than the war",

and

most of his later works "resonated with darkly tragic ironies that

can only be interpreted as critiques of Stalin's repressions." In 1943

Prokofiev joined Eisenstein in Alma-Ata,

the

largest city in Kazakhstan,

to

compose more film music (Ivan

the

Terrible), and the ballet Cinderella (Op. 87), one of his most

melodious and celebrated compositions. Early that year he also played

excerpts from War and Peace to

members of the Bolshoi Theatre collective. However, the Soviet

government had opinions about the opera which resulted in numerous

revisions. In 1944, Prokofiev moved to

a composer's colony outside Moscow in order to compose his Fifth

Symphony (Op. 100)

which would turn out to be the most popular of all his symphonies, both

within Russia and abroad. Shortly afterwards, he

suffered a concussion after a fall due to chronic high blood pressure. He never fully recovered

from this injury, which severely reduced his productivity rate in the

ensuing years, though some of his last pieces were as fine as anything

he had composed before. Prokofiev

had time to write his postwar Sixth

Symphony and a ninth

piano

sonata (for Sviatoslav

Richter) before the Party, as part of the so-called "Zhdanov

Decree", suddenly changed its opinion about his music. The end of the war allowed

overall creative attention to turn inward again, resulting in the Party

tightening its reins on domestic artists. Prokofiev's music was now

seen as a grave example of formalism, and

was branded as 'anti-democratic'. With a number of his works

banned, most concert and theatre administrators panicked and would not

program Prokofiev's music at all, leaving him in severe financial

straits. On 20

February 1948, Prokofiev's wife Lina was arrested for 'espionage', as

she tried to send money to her mother in Spain. She was sentenced to 20

years, but was eventually released after Stalin's death and later left

the Soviet Union. His

latest opera projects were quickly cancelled by the Kirov Theatre. This

snub, in combination with his declining health, caused Prokofiev to

withdraw more and more from active musical life. His doctors ordered

him to limit his activities, which resulted in him spending only an

hour or two each day on composition. In 1949 he wrote his Cello Sonata

in C, Op. 119, for the 22-year old Mstislav

Rostropovich, who gave the first performance in 1950, with

Sviatoslav Richter. The last public performance of his lifetime was the

première of the Seventh

Symphony in 1952, a

piece of somewhat bittersweet character. The music was written for a

children's television program. Prokofiev

died at the age of 61 on 5 March 1953: the same day as Joseph

Stalin. He had lived near Red

Square, and for three days the throngs gathered to mourn Stalin,

making it impossible to carry Prokofiev's body out for the funeral

service at the headquarters of the Soviet Composer's Union. Paper

flowers and a taped recording of the funeral march from Romeo and Juliet had to be used, as all real

flowers and musicians were reserved for Stalin's funeral. He

is

buried in the Novodevichy

Cemetery in Moscow. The

leading Soviet musical periodical reported Prokofiev's death as a brief

item on page 116. The first 115 pages were devoted to the death of

Stalin. Usually Prokofiev's death is attributed to cerebral

hemorrhage (bleeding

into

the brain). Nevertheless it is known that he was chronically ill

for eight years before he died,

which

is why the precise nature of Prokofiev's terminal illness is

uncertain. Lina

Prokofieva outlived her estranged husband by many years, dying in London in early 1989. Royalties

from her late husband's music provided her with a modest income. Their

sons Sviatoslav (born 1924), an architect, and Oleg (1928 – 1998), an artist,

painter, sculptor and poet, have dedicated a large part of their lives

to the promotion of their father's life and work.