<Back to Index>

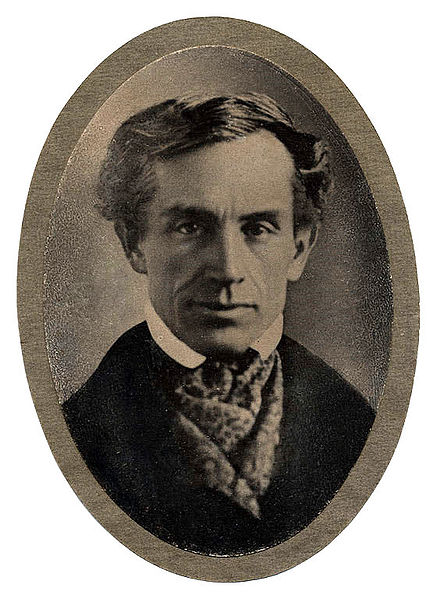

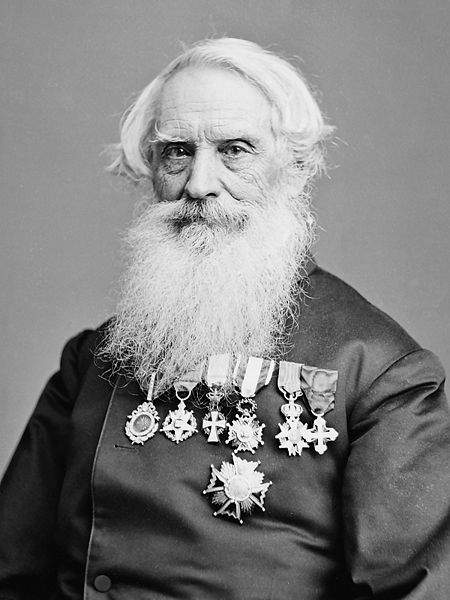

- Inventor Samuel Finley Breese Morse, 1791

- Composer Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev, 1891

- Queen Consort of Spain Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies, 1806

PAGE SPONSOR

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (27 April 1791 – 2 April 1872) was an American contributor to the invention of a single-wire telegraph system based on European telegraphs, co-inventor of the Morse code, and an accomplished painter.

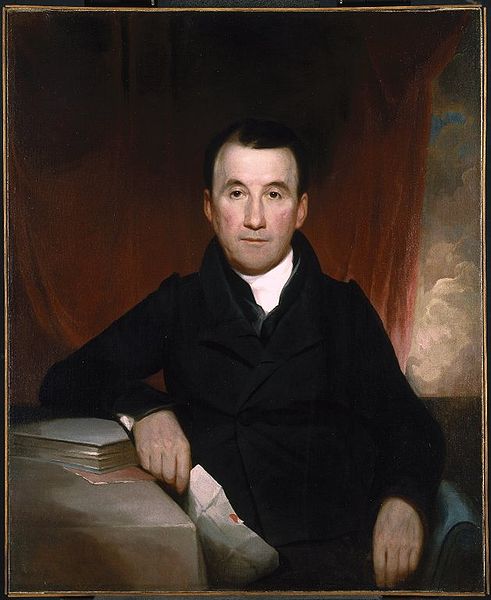

Samuel F.B. Morse was born in Charlestown, Massachusetts, the first child of a geographer and Pastor Jedidiah Morse (1761 – 1826) and Elizabeth Ann Finley Breese (1766 – 1828). Jedidiah was a great preacher of the Calvinist faith and supporter of the American Federalist party. He not only saw it as a great preserver of Puritan traditions (strict observance of the Sabbath), but believed in its idea of an alliance with Britain in regards to a strong central government. Jedidiah strongly believed in education within a Federalist framework alongside the instillation of Calvinist virtues, morals and prayers for his son. After attending Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, Samuel Morse went on to Yale College to receive instruction in the subjects of religious philosophy, mathematics and science of horses. While at Yale, he attended lectures on electricity from Benjamin Silliman and Jeremiah Day. He supported himself financially by painting. In 1810, he graduated from Yale with Phi Beta Kappa honors.

Morse's Calvinist beliefs are evident in his painting the Landing of the Pilgrims, through the depiction of simple clothing as well as the austere facial features. This image captured the psychology of the Federalists; Calvinists from England brought to the United States ideas of religion and government thus forever linking the two countries. More importantly, this particular work attracted the attention of the famous artist, Washington Allston. Allston wanted Morse to accompany him to England to meet the artist Benjamin West. An agreement for a three-year stay was made with Jedidiah, and young Morse set sail with Allston aboard the Lydia on July 15, 1811.

Upon his

arrival in England, Morse diligently worked to perfect painting

techniques under Allston's watchful eye; by the end of 1811, he gained admittance to the Royal

Academy. At the Academy, he fell in love with the Neo-classical art of the Renaissance and paid close attention to Michelangelo and Raphael.

After

observing and practicing life

drawing and

absorbing its anatomical demands, the young artist successfully

produced his masterpiece, the Dying

Hercules. To some,

the Dying Hercules seemed to represent a

political statement against the British and also the American

Federalists. The muscles apparently symbolized the strength of the

young and vibrant United States versus the British and British-American

supporters. During Morse’s time in Britain the Americans and British

were engaged in the War

of

1812 and

division existed within United States society over loyalties.

Anti-Federalist Americans aligned themselves with the French, abhorred

the British, and believed a strong central government to be inherently

dangerous to democracy. As the war raged on, his letters to his

parents became more anti-Federalist in tone. In one such letter Morse

said, "I assert that the Federalists in the Northern States have done

more injury to their country by their violent opposition measures than

a French alliance could. Their proceedings are copied into the English

papers, read before Parliament,

and circulated through their country, and what do they say of them...

they call them (Federalists) cowards, a base set, say they are traitors to their country and ought to be hanged like traitors." Although

Jedidiah did not change his political views, he did influence Morse’s

in another way. It is unmistakably clear that Jedidiah’s Calvinist

ideas were an integral part of Morse’s other significant English piece Judgment of Jupiter. Jupiter in the cloud, accompanied

by his eagle,

with

his hand over the parties, is pronouncing judgment. Marpessa with an expression of

compunction and shame, imploring forgiveness, is throwing herself into

the arms of her husband. Idas, who tenderly loved Marpessa, is eagerly

rushing forward to receive her, while Apollo stares

with

surprise… at the unexpectedness of her decision...

A case

can be made that Jupiter is representative of God’s

omnipotence watching every move that is made. One might deem the

portrait as a moral teaching by Morse on infidelity.

Although

Marpessa fell victim she realized that her eternal

salvation was

important and desisted from her wicked ways. Apollo shows no remorse

for what he did, but just stands there with a puzzled look. A lot of

the American paintings throughout the early nineteenth century had

religious themes and tones and it was Morse who was the forerunner. Judgment of Jupiter allowed Mr. Morse to

express his support of Anti Federalism while maintaining his strong

spiritual convictions. This work represented American nationalism

through Calvinism because these individuals expelled from England,

contributed to the expulsion of the British (1776 and now in 1812) and

established a free democratic society. West sought to present this

image at another Royal Academy exhibition; unfortunately his time had

run out. He left England on August 21, 1815 and began his full-time

career as an American painter. The years

1815 – 1825 marked significant growth in Morse’s paintings as he sought

to capture the essence of America’s culture and life. He had the honor

of painting former Federalist President John

Adams (1816). He

hoped to become part of grander projects and saw his opportunity with

the clash between Federalist and Anti-Federalists over Dartmouth

College. Morse was able to paint Judge Woodward (1817) who was

involved in bringing the

Dartmouth

case before

the U.S.

Supreme

Court and

the college’s president, Francis

Brown. He sought commissions in Charleston,

South

Carolina (1818).

Morse’s painting of Mrs. Emma Quash symbolized the opulence of

Charleston. It seemed for the time being, the young artist was doing

well for himself. Between

1819 and 1821, Morse experienced a great change in his life. Nothing

stayed the same after that. Commissions ceased in Charleston when the

city was hit with an economic recession related to the Panic

of

1819. Jedidiah was forced to resign from his ministerial position as he was unsuccessful in stopping the rift within Calvinism.

The new branch that formed was the Congregational Unitarians which he

deemed as detestable anti-Federalists because these persons took a

different approach over salvation. Although he respected his father’s

religious opinions, he sympathized with the Unitarians.

A

prominent family that converted to the new Calvinist faith was the

Pickerings of Portsmouth whom Morse had painted. This portrait can then

be viewed as a further shift towards anti-Federalism. A person could

argue that he made his full transition to anti-Federalism when he was

commissioned to paint President James

Monroe (1820). Monroe embodied Jeffersonian Democracy by favoring the common man over

the aristocrat; later reemphasized upon the ascension of Andrew Jackson. There

were two defining commissions that shaped Morse’s art career from his

return to New

Haven until the

establishment of the National Academy

of Design. The Hall of Congress (1821) and the Marquis

de

Lafayette (1825)

engaged Morse’s sense of democratic nationalism. The Hall of Congress

was designed to capitalize on the astonishing success of

François-Marius Granet's The

Capuchin

Chapel in Rome which

toured

the United States extensively throughout the 1820s, attracting

audiences willing to pay the 25-cent admission fee. The artist chose to paint

the House

of

Representatives, in a similar way, with careful attention to

architecture and dramatic lighting. He also wished to select a uniquely

American topic that would bring glory to the young nation, and his

topic did just that, showing American democracy in action. He traveled

to Washington

D.C. to draw the

architecture of the new halls, carefully placing eighty individuals

within the painting and believed that a night scene was appropriate. He

successfully balanced the architecture of the Rotunda with the

figurines and the glow of the lamplight serving as the focal point of

the work. Pairs of people, those who stood alone, individuals bent over

their desks working were painted simply but had characterized faces.

Morse chose nighttime to convey Congress’ dedication to the principles

of democracy transcended day. The Hall of Congress however, failed to

draw a crowd in New

York

City. One possible reason for the disappointment was the

shadow of John Trumbull’s Declaration of Independence that won popular

acclaim in 1820. A second explanation is that the overwhelming

attention to the architecture of the Hall of Congress overshadows the

individuals, making it hard to appreciate the drama of what was

actually happening. Morse

felt a great degree of honor of painting the Marquis

de

Lafayette, leading supporter of the American

Revolution. He felt compelled to paint a grandiose portrait of the

man who helped to establish a free and independent America. In his

image, he enshrouds Lafayette with a magnificent sunset as he stands to

the right of three pedestals of which two are Benjamin

Franklin and George

Washington with the final reserved for him. A peaceful wooden

landscape below him symbolized American tranquility and prosperity as

it approach the age of fifty. The developing friendship between Morse

and Lafayette and the discussion of the Revolutionary War, affected the

artist upon returning to New York City. Morse was

in Europe for three years improving

his painting skills, 1830 – 1832, travelling in Italy, Switzerland and France.

The

project he eventually selected was to paint miniature copies of

some 38 of the Louvre's

famous

paintings on a single canvas (6 ft. x 9 ft) which he

entitled The Gallery

of the Louvre, planning to complete the work upon his return to the

United States. On a subsequent visit to Paris in 1839, Morse met Louis

Daguerre and became

interested in the latter's daguerreotype,

the

first practical means of photography.

Morse

wrote a letter to the New-York

Observer describing

the invention, which was published widely in the American press and

provided a broad awareness. In 1825,

the city of New

York commissioned

Morse for $1,000 to paint a portrait of Gilbert

du

Motier, marquis de Lafayette, in Washington. In the midst of

painting, a horse messenger delivered a letter from his father that

read one line, "Your dear wife is convalescent". Morse immediately left

Washington for his home at New

Haven, leaving the portrait of Lafayette unfinished. By the time he arrived she had already been buried. Heartbroken in the

knowledge that for days he was unaware of his wife's failing health and

her lonely death, he moved on from painting to pursue a means of rapid long

distance

communication. On the

sea voyage home in 1832, Morse encountered Charles

Thomas

Jackson of Boston who was well schooled in electromagnetism. Witnessing

various experiments with Jackson's electromagnet,

Morse

developed the concept of a single-wire telegraph,

and The Gallery of the Louvre was set

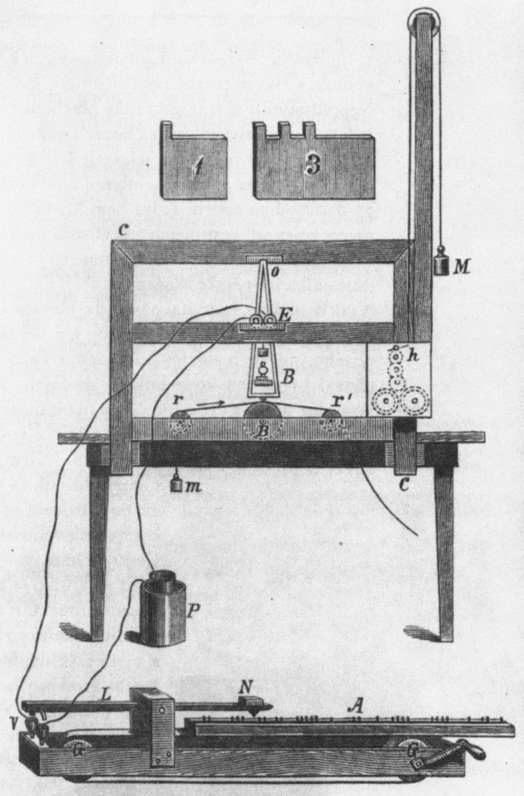

aside. The original Morse telegraph, submitted with his patent application, is part of the

collections of the National

Museum of American History at

the Smithsonian

Institution. In time the Morse

code would become

the primary language of telegraphy in the world, and is still the

standard for rhythmic transmission of data. William

Cooke and Professor Charles

Wheatstone learned

of the Wilhelm

Weber and Carl

Gauß electromagnetic

telegraph

in 1833, and reached the stage of launching a commercial

telegraph prior to Morse, despite starting later. In England, Cooke

became fascinated by electrical telegraph in 1836, four years after

Morse, but with greater financial resources. Cooke abandoned his

primary subject of anatomy and built a small

electrical telegraph within three weeks. Wheatstone also was

experimenting with telegraphy and (most importantly) understood that a

single large battery would not carry a

telegraphic signal over long distances, and that numerous small

batteries were far more successful and efficient in this task

(Wheatstone was building on the primary research of Joseph

Henry, an American physicist).

Cooke

and Wheatstone formed a partnership and patented the electrical

telegraph in May 1837, and within a short time had provided the Great

Western

Railway with

a 13-mile (21 km) stretch of telegraph. However, Cooke and

Wheatstone's multiple wire signaling method would be overtaken by

Morse's superior method within a few years. In a

letter to a friend, Morse describes how vigorously he fought for being

called the sole inventor of the electromagnetic telegraph despite the previous

inventions (1848). Morse

encountered the problem of getting a telegraphic signal to carry over

more than a few hundred yards of wire. His breakthrough came from the

insights of Professor Leonard Gale, who taught chemistry at New

York

University (a

personal friend of Joseph

Henry). With Gale's help, Morse soon was able to send a message

through ten miles (16 km) of wire. This was the great breakthrough

Morse had been seeking. Morse and Gale were soon joined by a young

enthusiastic man, Alfred

Vail, who had excellent skills, insights and money. Morse's

telegraph now began to be developed very rapidly. In 1838 a

trip to Washington,

D.C., failed to attract federal sponsorship for a telegraph line.

Morse then traveled to Europe seeking both sponsorship and patents, but

in London discovered Cooke and Wheatstone had already established

priority. Morse would need the financial backing of Maine congressman Francis

Ormand

Jonathan Smith. Morse

made one last trip to Washington, D.C., in December 1842, stringing

"wires between two committee rooms in the Capitol, and sent messages

back and forth" to demonstrate his telegraph system. Congress

appropriated $30,000 in 1843 for construction of an experimental

38-mile (61 km) telegraph line between Washington, D.C., and Baltimore,

Maryland, along the right-of-way of the Baltimore

and Ohio Railroad. An impressive demonstration

occurred on May 1, 1844, when news of the Whig

Party's nomination of Henry

Clay for U.S. President was telegraphed from the party's convention in Baltimore to

the Capitol Building in Washington.

On

May 24, 1844, the line was officially opened as Morse sent the

famous words "What

hath

God wrought" from the B&O's Mount

Clare

Station in

Baltimore to the Capitol Building along the wire. Annie Ellsworth chose these

words from the Bible (Numbers 23:23); her father, U.S.

Patent

Commissioner Henry

Leavitt

Ellsworth, had championed Morse's invention and secured

early funding for it. In May

1845 the Magnetic Telegraph Company was formed in order to radiate

telegraph lines from New

York

City towards Philadelphia, Boston, Buffalo,

New

York and the Mississippi. Morse

also at one time adopted Wheatstone and Carl

August

von Steinheil's idea of broadcasting an electrical telegraph

signal through a body of water or down steel railroad tracks or

anything conductive. He went to great lengths to win a law suit for the right to be called

"inventor of the telegraph", and promoted himself as being an inventor,

but Alfred

Vail played an

important role in the invention of the Morse Code, which was based on earlier codes for the electromagnetic

telegraph. Samuel

Morse received a patent for the telegraph in 1847, at the old

Beylerbeyi Palace (the present Beylerbeyi

Palace was built in

1861 – 1865 on the same location) in Istanbul,

which

was issued by Sultan

Abdülmecid who

personally tested the new invention. In the

1850s, Morse went to Copenhagen and visited the Thorvaldsens

Museum, where the sculptor's grave is in the inner courtyard. He

was received by King

Frederick

VII, who decorated him with the Order

of

the Dannebrog. Morse expressed his wish to donate his portrait

from 1830 to the king. The Thorvaldsen portrait today belongs to Margaret

II

of Denmark. The Morse

telegraphic apparatus was officially adopted as the standard for

European telegraphy in 1851. Only the United

Kingdom (with its extensive overseas British

Empire) kept the needle telegraph of Cooke and Wheatstone. There is

an argument amongst historians that Morse may have received the idea of

a plausible telegraph from Harrison

Gray

Dyar some

eighteen years earlier than his patent. According

to his The New York

Times obituary

published on April 3, 1872, Morse received respectively the decoration

of the Atiq

Nishan-i-Iftikhar (English:

Order

of Glory), set in diamonds, from the Sultan

Ahmad

I ibn Mustafa of Turkey (c.1847),

a golden snuff box

containing the Prussian gold medal for scientific merit from the King of Prussia

(1851); the Great

Gold Medal of Arts and Sciences from

the King

of

Württemberg (1852);

and

the Great Golden

Medal of Science and Arts from Emperor

of

Austria (1855);

a cross of Chevalier in the Légion

d'honneur from the

Emperor of France; the Cross

of

a Knight of the Order

of

the Dannebrog from

the King of Denmark (1856); the Cross of Knight Commander of the Order

of

Isabella the Catholic, from the Queen of Spain, besides being

elected member of innumerable scientific and art societies in the United States and other countries. Other awards include Order

of

the Tower and Sword from the

kingdom of Portugal (1860); and Italy conferred on him the insignia

of chevalier of the Order

of

Saints Maurice and Lazarus in

1864. In the

United States, Morse had his telegraph patent for many years, but it

was both ignored and contested. In 1853 the

case

of the patent came

before the U.S.

Supreme

Court where,

after very lengthy investigation, Chief

Justice Roger

B.

Taney ruled that

Morse had been the first to combine the battery, electromagnetism,

the electromagnet and the correct battery

configuration into a workable practical telegraph. Nevertheless, in

spite of this clear ruling, Morse still received no official

recognition from the United

States

government. Assisted

by the American

ambassador in

Paris, the governments of Europe were approached regarding how they had

long neglected Morse while using his invention. There was then a

widespread recognition that something must be done, and "in 1858 Morse

was awarded the sum of 400,000 French

francs (equivalent

to about $80,000 at the time) by the governments of France, Austria, Belgium,

the Netherlands, Piedmont, Russia, Sweden, Tuscany and Turkey,

each

of which contributed a share according to the number of Morse

instruments in use in each country." In 1858, he was also elected a

foreign member of the Royal

Swedish

Academy of Sciences. There was

still no such recognition in the U.S. This remained the case until June

10, 1871, when a bronze statue of Samuel Morse was unveiled in Central

Park, New

York

City. An engraved portrait of Morse appeared on the reverse

side of the United

States

two-dollar bill silver certificate series

of 1896. He was depicted along with Robert

Fulton. An example can be seen on the website of the Federal

Reserve Bank of San Francisco's website in their "American Currency

Exhibit". A blue

plaque was erected

to commemorate him at 141 Cleveland Street, London,

where

he lived from 1812 to 1815. In

addition to the telegraph, Morse invented a marble-cutting machine that could carve three

dimensional sculptures in marble or stone. Morse couldn't patent it, however, because of an existing 1820 Thomas

Blanchard design. In the

1850s, Morse became well known as a defender of America's institution of slavery,

considering

it to be sanctioned. In his treatise "An Argument on the

Ethical Position of Slavery," he wrote: My

creed on the subject of slavery is short. Slavery per se is not sin. It

is a social condition ordained from the beginning of the world for the

wisest purposes, benevolent and disciplinary, by Divine Wisdom. The

mere holding of slaves, therefore, is a condition having per se nothing

of moral character in it, any more than the being a parent, or

employer, or ruler. Samuel

Morse was a generous man who gave large sums to charity. He also became

interested in the relationship of science and religion and provided the

funds to establish a lectureship on 'the relation of the Bible to the

Sciences'. Morse was not a selfish man. Other people and corporations

made millions using his inventions, yet most rarely paid him for the

use of his patented telegraph. He was not bitter about this, though he

would have appreciated more rewards for his labors. Morse was

comfortable; by the time of his death, his estate was valued at some

$500,000.

Morse

died

on April 2, 1872, 25 days short of his 81st birthday. He died of pneumonia.

He

was at his home at 5 West 22nd Street, New

York City, at the age of 80, and was buried in the Green-Wood

Cemetery in Brooklyn,

New

York. Morse was

a leader in the anti-Catholic and anti-immigration

movement of the mid-19th century. In 1836, he ran unsuccessfully for mayor of

New York under

the anti-immigrant Nativist

Party's banner, receiving only 1496 votes. When Morse visited Rome,

he

refused to take his hat off in the presence of the Pope.

Upon

seeing this, an offended Swiss

Guardsman rushed

over and hit the hat off of his head. Morse worked to unite Protestants

against Catholic institutions (including schools), wanted to forbid

Catholics from holding public office, and promoted changing immigration

laws to limit immigration from Catholic countries. On this topic, he

wrote, “We must first stop the leak in the ship through which muddy

waters from without threaten to sink us.” Morse was

the author of a number of letters to the New York Observer (his brother Sidney was the

editor at the time) urging people to fight the perceived Catholic

menace. These articles were widely reprinted in other newspapers. Among

other claims, he believed that the Austrian

government and

Catholic aid organizations were subsidizing Catholic immigration to the

United States in order to gain control of the country. In his Conspiracy Against the

Liberties of the United States, Morse wrote: “Surely American

Protestants, freemen, have discernment enough to discover beneath them

the cloven foot of this subtle foreign heresy. They will see that Popery is now, what it has ever

been, a system of the darkest political intrigue and despotism,

cloaking itself to avoid attack under the sacred name of religion. They

will be deeply impressed with the truth, that Popery is a political as

well as a religious system; that in this respect it differs totally

from all other sects, from all other forms

of

religion in the country.”