<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Georgy Feodosevich Voronoy, 1868

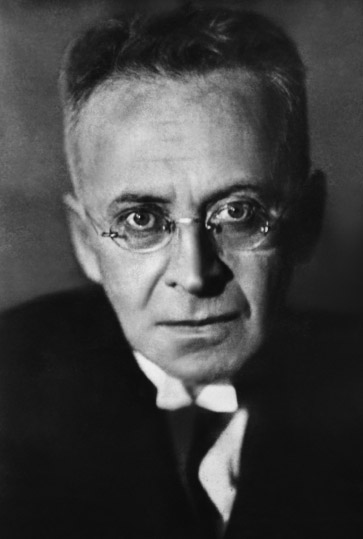

- Writer Karl Kraus, 1874

- Dictator of Portugal António de Oliveira Salazar, 1889

PAGE SPONSOR

Karl Kraus (April 28, 1874 – June 12, 1936) was an Austrian writer and journalist, known as a satirist, essayist, aphorist, playwright and poet. He is regarded as one of the foremost German language satirists of the 20th century, especially for his witty criticism of the press, German culture, and German and Austrian politics.

Kraus was born into a wealthy Jewish family of Jacob Kraus, a papermaker, and his wife Ernestine, née Kantor, in Gitschin, Bohemia (now Jičín in the Czech Republic). The family moved to Vienna in 1877. His mother died in 1891.

Kraus

enrolled as a law student at the University

of

Vienna in 1892.

Beginning in April of the same year he began contributing to the paper Wiener Literaturzeitung,

starting

with a critique of Gerhart

Hauptmann's Die

Weber. Around that time, he unsuccessfully tried to perform as an

actor in a small theater. In 1894 he changed his field of studies to

philosophy and German literature. He discontinued his studies in 1896.

His friendship with Peter

Altenberg began

about this time. In 1896

he left university without a diploma to begin work as an actor,

stage director and performer, joining the Jung

Wien (Young

Vienna) group, which included Peter

Altenberg, Leopold

Andrian, Hermann

Bahr, Richard

Beer-Hofmann, Felix

Dörmann, Hugo

von

Hofmannsthal, and Felix

Salten. In 1897, however, Kraus broke from this group with a biting

satire Die

demolierte Literatur (Demolished Literature), and was named Vienna correspondent for the newspaper Breslauer

Zeitung. One year later, as an uncompromising advocate of

Jewish assimilation, he attacked the founder of modern Zionism Theodor

Herzl with his

polemic Eine Krone

für Zion (A

Crown for Zion) (1898). On April

1, 1899, he renounced Judaism and in the same year

founded his own newspaper, Die

Fackel (The Torch),

which

he continued to direct, publish, and write until his death, and

from which he launched his attacks on hypocrisy, psychoanalysis, corruption of the Habsburg

empire, nationalism of the pan-German movement, laissez-faire economic policies, and

numerous other subjects. In 1901,

Kraus was sued by Hermann

Bahr and Emmerich

Bukovics, who felt they had been attacked by Die Fackel.

Many

lawsuits by diverse offended parties would follow in later years. Also

in 1901, Kraus found out that his publisher, Moriz Frisch, had taken

over his magazine while he was absent on a months long journey: Moriz

Frisch had registered the magazine's front cover as a trademark and

published the Neue

Fackel (New Torch).

Kraus

sued and won. From that time, Die Fackel was published (without a cover page) by the printer Jahoda & Siegel. While at

the beginning Die

Fackel was similar

to journals like the magazine Weltbühne,

it

became more and more a magazine that was privileged in its editorial

independence, which Kraus could provide by his funding. Die Fackel printed what Kraus wanted

to be printed. In its first decade, contributors included many

well-known writers and artists such as Peter

Altenberg, Richard

Dehmel, Egon

Friedell, Oskar

Kokoschka, Else

Lasker-Schüler, Adolf

Loos, Heinrich

Mann, Arnold

Schönberg, August

Strindberg, Georg Trakl, Frank

Wedekind, Franz

Werfel, Houston

Stewart

Chamberlain and Oscar

Wilde. After 1911, however, Kraus was usually the sole author.

Kraus' work was published nearly exclusively in Die Fackel, of which

922 irregularly issued numbers appeared in total. Authors who were

supported by Kraus include Peter

Altenberg, Else

Lasker-Schüler, and Georg

Trakl. Die

Fackel targeted

corruption, journalists and brutish behaviour. Notable enemies were Maximilian

Harden (in the mud

of the Harden-Eulenburg affair), Moriz

Benedikt (owner of

the newspaper Neue

Freie

Presse), Alfred

Kerr, Hermann

Bahr, Imre

Bekessy and Johannes

Schober. In 1902,

Kraus published Sittlichkeit

und

Kriminalität (Morality

and

Criminal Justice), for the first time commenting on what was to

become one of the main issues in his writings: the allegedly necessary

defense of sexual morality by means of criminal justice (Der Skandal

fängt an, wenn die Polizei ihm ein Ende macht, The scandal starts when

the police is stopping it). Starting in 1906, Kraus published the first of his aphorisms in Die Fackel; they

were collected in 1909 in the book Sprüche und Widersprüche (Sayings and Gainsayings). In

addition to his writings, Kraus gave numerous highly influential public

readings during his career - between 1892 and 1936 he put on approximately 700 one-man performances, reading from the dramas of Bertolt

Brecht, Gerhart

Hauptmann, Johann

Nestroy, Goethe, and Shakespeare,

and

also performing Offenbach's

operettas,

accompanied by piano and singing all the roles himself. Elias Canetti, who regularly attended Kraus' lectures, titled the second

volume of his autobiography "Die

Fackel"

im Ohr ("The

Torch" in the Ear) in reference to the magazine and its author. At

the peak of his popularity, Kraus' lectures attracted four thousand people, and his magazine sold forty thousand copies. In 1904,

Kraus supported Frank

Wedekind to make

possible the staging in Vienna of his controversial play, Pandora's

Box; the

play told the story of a sexually-enticing young dancer who rises in

German society through her relationships with wealthy men, but who

later falls into poverty and prostitution. The frank depiction of

sexuality and violence in these plays, including lesbianism and an encounter with Jack

the

Ripper, pushed

the boundaries of

what was considered acceptable on the stage at the time. Wedekind's

works are considered among the precursors of the expressionists, but in

1914, when expressionist poets like Richard

Dehmel sold

themselves to war propaganda, Kraus would become a fierce critic of them. In 1907,

Kraus attacked his erstwhile benefactor Maximilian

Harden because of

his role in the Eulenburg

trial in the first

of his spectacular Erledigungen (Dispatches). After

1911, Kraus was the sole author of most issues of Die Fackel. One of

Kraus' most influential satirical literary techniques, was his detournement of quotations. One example

controversy arose with the text Die

Orgie, which exposed how the newspaper Neue

Freie

Presse was

blatantly supporting Austria's

Liberal

Party's election campaign; the text was conceived as a

guerrilla prank and sent as a fake letter to the newspaper (Die

Fackel will publish

it later in 1911); the enraged editor, which fell into the trick,

responded by suing Kraus for "disturbing the serious business of

politicians and editors". After an

obituary for Franz

Ferdinand who had

been assassinated

in

Sarajevo on 28

June 1914, Die Fackel was not published for many months. In December 1914, it appeared again with an essay "In dieser

großen Zeit" ("In this grand time"): "In dieser großen

Zeit, die ich noch gekannt habe, wie sie so klein war; die wieder klein

werden wird, wenn ihr dazu noch Zeit bleibt; … in dieser lauten Zeit,

die da dröhnt von der schauerlichen Symphonie der Taten, die

Berichte hervorbringen, und der Berichte, welche Taten verschulden: in

dieser da mögen Sie von mir kein eigenes Wort erwarten." ("In this grand time that I

still know from when it was very small; that will become small again if

it has the time; … in this loud time that resounds from the ghastly

symphony of deeds that spawn reports, and from reports that are to

blame for deeds: in this one, you may not expect any word of my own.")

In the subsequent time, Kraus wrote against the World War, and editions

of Die Fackel were repeatedly confiscated

or obstructed by censors. Kraus'

masterpiece is generally considered to be the massive satiric play

about the First

World

War, Die

letzten

Tage der Menschheit (The

Last

Days of Mankind), which combines dialogue from

contemporary documents with apocalyptic fantasy and

commentary from two characters called "the Grumbler" and "the

Optimist". Kraus began to write the play in 1915 and first published it

as a series of special Fackel issues in 1919. Its

epilogue, "Die letzte Nacht" ("The last night") had already been

published in 1918 as a special issue. Edward

Timms has

called

the work a "faulted masterpiece" and a "fissured text" because the

evolution of Kraus' attitude during the time of its composition (from aristocratic conservative to democratic republican)

means

that the text has structural inconsistencies resembling a geological

fault. The play was first staged,

with more than sixty actors, by Italian director Luca

Ronconi in Turin in 1991, soon after the First

Gulf

War. Also in

1919, Kraus published his collected war texts under the title Weltgericht (World court of justice).

In

1920, he published the satire Literatur

oder

Man wird doch da sehn (Literature

or

You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet) as a reply to Franz

Werfel's Spiegelmensch (Mirror man), an

attack against Kraus. During

January 1924, he started to fight against Imre Békessy,

publisher of the tabloid Die

Stunde (The Hour).

Kraus

accused Békessy of extorting money from restaurant owners

by threatening them with bad reviews in his paper unless they paid him.

Békessy retaliated with a libel campagne against Kraus, who in

turn launched an Erledigung with the catchphrase

"Hinaus aus Wien mit dem Schuft!" ("Throw the scoundrel out of

Vienna"). In 1926, Békessy indeed fled Vienna in order to avoid

being arrested. Békessy achieved some later success when his

novel Barabbas was the monthly selection

of an American book club. In 1927,

a peak in Kraus's political commitment was his sensational attack on

powerful Vienna police chief Johann

Schober, also former two terms chancellor, after 84 people were

shot dead in the police massacre of the July

Revolt. Karl Kraus produced a poster that in a single sentence

requested Schober's resignation; the poster was published all over

Vienna and is considered an icon of Austrian 20th century history. In 1928,

the play Die

Unüberwindlichen (The

insurmountables) was published. It included allusions to the fights

against Békessy and Schober. During that same year, Kraus also

published the records of a lawsuit that Kerr had filed against him

after Kraus had published Kerr's war poems in Die Fackel. In 1932,

Kraus translated Shakespeare's sonnets. Kraus

supported the Social

Democratic

Party of Austria since

at

least the early 1920s. And in 1934, estranging

himself from some of his followers, he supported Engelbert

Dollfuss' coup d'état that established the Austrian fascist

regime, hoping Dollfuß could prevent Nazism from engulfing

Austria. One of

his last works, which he declined to publish for fear of Nazi

reprisals, was the verbally rich, densely allusive anti-Nazi polemic Die Dritte Walpurgisnacht (The Third Walpurgis

Night) of 1933. This satire on Nazi ideology begins with the

now-famous sentence, "Mir fällt zu Hitler nichts ein" (Hitler

brings nothing to my mind). However, lengthy extracts appear in his

apologia for his silence at Hitler's coming to power, Warum die Fackel nicht

erscheint (Why

the Fackel Does Not Appear), a 315-page edition of his periodical.

The last issue of the Fackel appeared in February 1936.

Karl Kraus died of an embolism of the heart in Vienna on

June 12, 1936 after a short illness. Kraus

never married, but from 1913 until his death, he had a conflict-prone

but close relationship with the Baroness Sidonie Nádherný

von Borutin (1885 – 1950). Many of his works were written in the

Janowitz

castle, a Nádherny family property. Sidonie Nádherny

became

an important pen-friend and addressee of books and poems. In 1911

he was baptized as a Catholic,

but

in 1923, disillusioned over the Church's support for the war, he

left the Catholic

Church, claiming sarcastically that he was motivated "primarily by

antisemitism", i.e. indignation at Max

Reinhardt's use of the Kollegienkirche in Salzburg as the venue

for a theatrical performance. Kraus is buried in the Zentralfriedhof cemetery outside Vienna. Kraus was

the subject of two books written by noted libertarian author Dr. Thomas

Szasz. Karl

Kraus and the Soul Doctors and Anti-Freud: Karl

Kraus's Criticism of Psychoanalysis and Psychiatry portrayed Kraus as a harsh

critic of Sigmund

Freud and of psychoanalysis in general. Other

commentators, such as Edward

Timms, have argued that Kraus respected Freud, though with

reservations about the application of some of his theories, and that

his views were far less black-and-white than Szasz suggests.