<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Georgy Feodosevich Voronoy, 1868

- Writer Karl Kraus, 1874

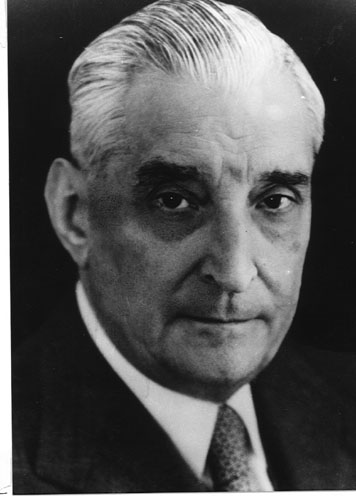

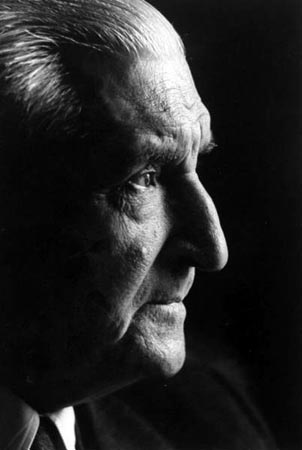

- Dictator of Portugal António de Oliveira Salazar, 1889

PAGE SPONSOR

António de Oliveira Salazar (28 April 1889 – 27 July 1970) served as the Prime Minister of Portugal from 1932 to 1968. He also served as acting President of the Republic for most of 1951. He founded and led the Estado Novo (New State), the authoritarian, right-wing government that presided over and controlled Portugal from 1932 to 1974. According to some Portuguese scholars like Jaime Nogueira Pinto and Rui Ramos, his early reforms and policies changed the whole nation since they allowed political and financial stability and therefore social order and economic growth, after the politically unstable and financially chaotic years of the Portuguese First Republic (1910 – 1926). Salazar's program was opposed to communism, socialism, and liberalism. It was pro-Roman Catholic, conservative, and nationalistic. Its policy envisaged the perpetuation of Portugal as a pluricontinental empire, financially autonomous and politically independent from the dominating superpowers, and a source of civilization and stability to the overseas societies in the African and Asian possessions. Salazar's regime and its secret police repressed elemental civil liberties and political freedoms in order to remain sole ruler of Portugal, avoiding communist influences and the dissolution of its coveted empire. António Óscar Carmona, who masterminded the National Revolution that established the Ditadura Nacional, which in turn paved the way for the Estado Novo, retained formal powers along with Salazar as President, until his death in 1951.

Salazar was born in Vimieiro, near Santa Comba Dão, to a family of modest income. His father, a small landowner, had started as an agricultural labourer and became the manager of a distinguished family of rural landowners of the region of Santa Comba Dão, the Perestrelos, who possessed lands and other assets scattered between Viseu and Coimbra. He had four older sisters, and was the only male child of two fifth cousins, António de Oliveira (17 January 1839 to 28 September 1932) and wife Maria do Resgate Salazar (23 October 1845 to 17 November 1926), whose paternal grandfather was a landowner and a nobleman. Despite the knowledge of his ancestry, Salazar always preferred to claim humble origins. His older sisters were Maria do Resgate Salazar de Oliveira, an elementary school teacher; Elisa Salazar de Oliveira; Maria Leopoldina Salazar de Oliveira; and Laura Salazar de Oliveira, who in 1887 married Abel Pais de Sousa, whose brother Mário Pais de Sousa was Salazar's Interior Minister, sons of a family of Santa Comba Dão, Santa Comba Dão.

Salazar studied at the Viseu Seminary from 1900 to 1914 and considered becoming a priest, but changed his mind. He studied law at Coimbra University during the first years of the republican government.

As a young man, his involvement in politics stemmed from his Catholic views, which were aroused by the new anti-clerical Portuguese First Republic. Writing in Catholic newspapers and fighting in the streets for the rights and interests of the Church and its followers were his first forays into public life.

During Sidónio Pais's brief dictatorship from 1917 to 1918, Salazar was invited to become a minister, but declined. He formally entered politics in the following years, joining the conservative Catholic Centre, and was elected to Parliament but left it after one session. He taught political economy at the University of Coimbra.

After the 28th May 1926 coup d'état, he briefly joined José Mendes Cabeçadas's government as the 71st Minister of Finance on 3 June 1926, but quickly resigned, explaining that since disputes and social disorder existed in the government, he could not do his work properly. Later again, he became the 81st Finance Minister on 26 April 1928, after the Ditadura Nacional was consolidated, paving the way for him to be appointed the 101st Prime Minister in 1932. He remained Finance Minister until 1940, when World War II consumed his time.

His rise

to power is due to the image he was able to build as an honest and

effective Finance Minister, President Carmona's

strong

support, and political positioning. The authoritarian government

consisted of a right-wing coalition, and Salazar was able to co-opt the

moderates of each political current while fighting the extremists,

using censorship and repression. The Catholics were his earliest and most loyal supporters, although some resented the continued separation

of

church and state. The conservative republicans who could not be

co-opted became his most dangerous opponents during the early period.

They attempted several coups, but never presented a united front, so

these coups were easily repressed. Never a true monarchist, Salazar

nevertheless gained most of the monarchists' support, as he had the

support of the exiled deposed

king, who was given a state funeral at the time of his death.

The National Syndicalists were torn between supporting the regime and denouncing it as bourgeois. They were given enough symbolic concessions to win over the moderates, and the rest were repressed by the political police. They were to be silenced shortly after 1933, as Salazar attempted to prevent the rise of National Socialism in Portugal. Salazar also supported Francisco Franco and the Nationalists in their fight against the left-wing groups of the Spanish Republic. The Nationalists lacked ports early on, and Salazar's Portugal helped receive armaments shipments from abroad - including ammunition early on when certain Nationalist forces were virtually out. Because of this, "the Nationalists referred to Lisbon as 'the port of Castile.'"

The

prevailing view, at the time, of political parties as elements of

division and parliamentarism as being in crisis led to general support,

or at least tolerance, of an authoritarian regime. In 1933,

Salazar introduced a new constitution which gave him wide powers,

establishing an anti-parliamentarian and authoritarian government that

would last four decades. Salazar

developed the "Estado Novo" (literally, New

State). The basis of his regime was a platform of stability. Salazar's

early

reforms allowed financial stability and therefore economic growth. This

was

then known as "A Lição de Salazar" - Salazar's Lesson.

Although

Portugal had a high level of illiteracy, the Salazar regime didn't consider

education a high priority and for many years didn't spend much on it,

beyond granting basic education to all citizens. However, in the final

years of Salazar's rule and the six years from his death to the fall of

the Estado Novo regime in 1974, educational

development

was prioritized and

there was substantial investment in educational infrastructure. At this

stage, secondary, vocational/technical and university education reached

record high enrollments. Many of the schools created by Salazar were

still in operation many decades after the end of the regime in 1974. Salazar's

regime was rigidly authoritarian. He based his political philosophy

around a close interpretation of Catholic

social

doctrine, much like the contemporary regime of Engelbert

Dollfuß in

Austria. The economic system, known as corporatism,

was

based on a similar interpretation of the papal encyclicals Rerum

Novarum (Leo XIII,

1891) and Quadragesimo

Anno (Pius XI,

1931), which was supposed to prevent class struggle and supremacy of

economics. Salazar himself banned Portugal's National

Syndicalists, a true Fascist party, for being, in his words, a

"Pagan" and "Totalitarian" party. Salazar's own party, the National

Union, was formed as a subservient umbrella organisation to support

the regime itself, and was therefore lacking in any ideology

independent of the regime. At the time many European countries feared

the destructive potential of communism.

Many

neutral states in World

War

II sympathized, at least in principle, with any state that would wage war on the Soviet

Union. Salazar not only forbade Marxist parties, but also

revolutionary fascist-syndicalist parties. Salazar

relied on the secret

police, first the PVDE (Polícia de

Vigilância e de Defesa do Estado - "State Defence and

Surveillance Police") set up in 1933 and modeled on the Gestapo and later the PIDE (Polícia

Internacional e de Defesa do Estado) established in 1945 and lasting

till 1969 (until 1974, under Marcelo

Caetano, the Estado Novo's police would be called DGS - Direcção

Geral de Segurança, "General Security Directorate"). The job

of the secret police was not just to protect national security in a

typical modern sense but also to suppress the regime's political

opponents, especially those related to the international communist

movement or the USSR which was seen by the

regime as a menace to Portugal. The PIDE was efficient, however, it was

less overtly brutal than its predecessor and the foreign polices that

were the model for its creation. A number of prisons were set up by

Salazar's right-wing authoritarian regime after the outbreak of the Spanish

Civil

War (1936),

where opponents of Estado

Novo were sent. The Tarrafal in Cape Verde archipelago

was one of them. Anarchists, communists, African

independence

movements guerrillas

and

other opponents of Salazar's regime died or were made prisoners for

many years in those prisons. Salazar

essentially ruled unopposed until the 1950s, when a new generation who

had no memory of the near-chaos that prevailed before 1926 gained

momentum. However, he was able to stay in power because the political

structure was heavily rigged in favour of the regime candidates. During World

War

II,

Salazar steered Portugal down a middle path, but

nevertheless provided aid to the Allies: naval bases on Portuguese

territory were granted to Britain, in keeping with the traditional

Anglo-Portuguese alliance, and the United States, letting them use Terceira

Island in the Azores as a military base;

although he only agreed to this after the alternative of an American

takeover by force of the islands was made clear to him by the British. Portugal, particularly Lisbon, was one of the

last European exit points to the U.S., and a huge number of refugees

found shelter in Portugal, many of them with the help from the

Portuguese consul general in Bordeaux, Aristides

de

Sousa Mendes, who issued visas against Salazar's orders. Siding

with the Axis would have meant that Portugal would have been at war with Britain,

which

would have threatened Portuguese colonies, while siding with the

Allies might prove to be a threat to Portugal itself. Portugal

continued to export tungsten and other goods to both the

Axis (partly via Switzerland) and Allied countries. Large

numbers of Jews and political dissidents, including Abwehr personnel after the 20 July

plot of 1944, sought refuge in Portugal, although until late 1942

immigration was very restricted. The

colonies were in disarray after the war. In 1945, Portugal had an

extensive colonial Empire, including Cape

Verde Islands, São

Tomé e Principe, Angola (including Cabinda), Portuguese

Guinea, and Mozambique in

Africa; Goa, Damão (including Dadra

and

Nagar Haveli), and Diu in India (the Portuguese

India); Macau in China; and Portuguese

Timor in Southeast

Asia. Salazar, a fierce integralist, was determined to retain

control of Portugal's colonies. The

overseas provinces were a continual source of trouble and wealth for

Portugal, especially during the Portuguese

Colonial

War. Portugal became increasingly isolated on the world

stage as other European nations with African colonies gradually granted

them independence. Salazar

wanted Portugal to be relevant internationally, and the country's

overseas colonies made this possible, while Salazar himself refused to

be overawed by the Americans. Portugal was the only non-democracy among

the founding members of NATO in 1949, which reflected

Portugal's role as an ally against communism during the Cold

War. Portugal was offered help from the Marshall

Plan because of the

aid it gave to the Allies during the final stages of World War II; aid

it initially refused but eventually accepted. Throughout

the

1950s, Salazar maintained the same import

substitution approach

to

economic policy that had ensured Portugal's neutral status during

World War II. The rise of the "new technocrats" in the early 1960s,

however, led to a new period of economic opening up, with Portugal as

an attractive country for international investment. Industrial

development and economic growth would continue all throughout the

1960s. During Salazar's tenure, Portugal also participated in the

founding of OECD and EFTA. The

Indian possessions were the first to be lost in 1961. After the Republic

of

India was formed

upon independence on August 15, 1947, the British and the French vacated their colonial

possessions in India.

Indian

nationalists in Goa launched a struggle for

Portugal to leave, involving a series of strikes and civil

disobedience movements

by

Indians against the Portuguese administration, which were ruthlessly

suppressed by Portugal. India made numerous offers to negotiate for the

return of the colonies, but Salazar repeatedly rejected the offers.

With an Indian military operation imminent, Salazar ordered Governor

General Manuel

António

Vassalo e Silva to

fight till the last man, and adopt a scorched

earth

policy. Eventually, India launched Operation

Vijay in Dec 1961

to evict Portugal from Goa, Daman

and

Diu. 31 Portuguese soldiers were killed in action and a

Portuguese Navy frigate NRP

Afonso

de Albuquerque was

destroyed, before General Vassalo e Silva surrendered. Salazar forced

the General into exile for disobeying his order to fight to the last

man and surrendering to the Indian

Army. In the

1960s, armed revolutionary movements and scattered guerrilla activity

had reached Mozambique, Angola, and Portuguese Guinea. Except in

Portuguese Guinea, the Portuguese army and naval forces were able to

effectively suppress most of these insurgencies through a well-planned

counter-insurgency campaign using light infantry, militia, and special

operations forces. Most of the world ostracized the Portuguese

government because of its colonial policy, especially the

newly independent African nations. At home,

Salazar's regime remained unmistakably authoritarian. He was able to

hold onto power with reminders of the instability that had characterized Portuguese political life before 1926. However, these

tactics were decreasingly successful, as a new generation emerged which

had no collective memory of this instability. In the 1960s, Salazar's

opposition to decolonization and gradual freedom

of the press created

friction with the Franco dictatorship.

Economically,

the

Salazar years were marked by immensely increased growth. From

1950

until Salazar's death, Portugal saw its GDP per capita rise at an

average rate of 5.66% per year. This

made

it the fastest growing economy in Europe. Indeed,

the

Salazar era was marked by an economic program based on the policies

of autarky and interventionism,

which

were popular in the 1930s as a response to the Great

Depression. During his tenure, Portugal was co-founder of OECD and EFTA.

Financial

stability was Salazar's highest priority. In

order

to balance the Portuguese budget and pay off external debts, he

instituted numerous taxes. Having adopted a policy of neutrality during

World War II, Portugal could simultaneously loan the Base das Lages in

the Azores to the Allies and export military equipment and metals to the Axis

powers. In 1960, at the initiation of Salazar's more

outward-looking economic policy, Portugal's per capita GDP was only 38

percent of the European Community (EC-12) average; by the end of the

Salazar period, in 1968, it had risen to 48 percent; and in 1973, under

the leadership of Marcelo

Caetano, Portugal's per capita GDP had reached 56.4 percent of the

EC-12 average. On a long term analysis,

after a long period of economic divergence before 1914, and a period of

chaos during the Portuguese

First

Republic, the Portuguese economy recovered slightly until

1950, entering thereafter on a path of strong economic convergence

until the Carnation

Revolution in April

1974. Portuguese economic growth in the period 1950 – 1973 under the

Estado Novo regime (and even with the effects of an expensive war

effort in African territories against independence guerrilla groups),

created an opportunity for real integration with the developed

economies of Western Europe. Through emigration, trade, tourism and

foreign investment, individuals and firms changed their patterns of

production and consumption, bringing about a structural transformation.

Simultaneously, the increasing complexity of a growing economy raised

new technical and organizational challenges, stimulating the formation

of modern professional and management teams. His

reluctance to travel abroad, his increasing determination not to grant

independence to the colonies and to stand against the "winds of

change" announced by the British in their move to liberate their

major colonies,

and

his refusal to grasp the impossibility of his regime outliving him,

marked the final years of his tenure. "Proudly alone" was the motto of

his final decade. For the Portuguese ruling regime, the overseas empire

was a matter of national identity. In order

to support his colonial policies, Salazar adopted Gilberto

Freyre's notion of Lusotropicalism,

maintaining

that since Portugal had been a multicultural, multiracial

and pluricontinental nation since the 15th century, if the country were

to be dismembered by losing its overseas territories, that would spell

the end for Portuguese independence. In geopolitical terms, no critical

mass would then be available to guarantee self-sufficiency to the

Portuguese State. Salazar had strongly resisted Freyre's ideas

throughout the 1930s, partly because Freyre claimed the Portuguese were

more prone than other European nations to miscegenation, and only

adopted Lusotropicalism after sponsoring Freyre on a visit to Portugal

and its colonies in 1951-2. Freyre's work "Aventura e Rotina" was a

result of this trip. Salazar

was a close friend of Rhodesian Prime

Minister Ian

Smith: after Rhodesia proclaimed its Unilateral

Declaration

of Independence from

Britain,

Portugal - though not officially recognizing the new Rhodesian

state - supported Rhodesia economically and militarily through the

neighbouring Portuguese colony of Mozambique until 1975, when FRELIMO took over Mozambique after

negotiations with the new Portuguese regime which had taken over after

the Carnation Revolution. Ian Smith later wrote in his The

Great Betrayal that

had Salazar lasted longer than he did, the Rhodesian government would

have survived to the present day, ruled by a moderate black majority

government under the name of 'Zimbabwe-Rhodesia'. Salazar's

goal was to establish a Catholic Social Order, wherein the state,

government and social institutions would base its laws of right and

wrong on what the Gospels and the Catholic

Church teach is

right and wrong. In this process, Salazar even dissolved Freemasonry in Portugal in 1935.

Salazar, a former seminary student, was keen to leave the Catholic

Church complete and entire liberty of action. He permitted the Catholic

religion to be taught in all schools, not just parochial schools.

(Non-Catholic parents who did not wish their children to receive this

instruction could have their children removed from these classes, as

the Catholic Faith was never forced on anyone); but throughout

Portugal, the Catholic education of the youth was greatly favored.

Another policy at this time was Salazar's legislation on marriage which

read “The Portuguese state recognizes the civil effects of marriages

celebrated according to canonical laws.” He then initiated into this

legislation articles which frowned upon divorce. Article 24 reads, “In

harmony with the essential properties of Catholic marriages, it is

understood that by the very fact of the celebration of a canonical

marriage, the spouses renounce the legal right to ask for a divorce.”

The effect of this law was that the number of Catholic marriages went

up. So that by 1960, nearly 91 percent of all marriages in the country

were canonical marriages. On July

4, 1937, Salazar was on his way to Mass at a private chapel in a

friend's house in the Barbosa du Bocage Avenue in Lisbon. As he stepped

out of the car, a Buick,

a

bomb exploded only 10 feet away (the bomb had been hidden in an iron

case). The bomb-blast left Salazar untouched (his chauffeur was

rendered deaf). The bishops argued in a collective letter in 1938, that

it was an "act of God" that had preserved Salazar's life in this

attempted assassination. Emídio Santana was the anarcho-syndicalist,

founder

of the Metallurgists National Union (Sindicato Nacional dos

Metalúrgicos), behind the assassination attempt. The official

car was replaced by an armoured Chrysler

Imperial. On May

13, 1938, when the bishops of Portugal fulfilled their vow and renewed

the National Consecration to the Immaculate

Heart

of Mary, Cardinal

Cerejeira acknowledged

publicly

that Our

Lady

of Fatima had,

"Spared Portugal the scourge of Communism". After Portugal avoided the

devastation of both the Spanish

Civil

War and the Second

World

War, Salazar's propaganda machine and the Catholic Church

also connected this to a miraculous dimension which made them profit

from the Catholic fervor of the masses. The Cristo-Rei, a

Catholic monument in Almada,

was

inaugurated on 17 May 1959 by Salazar. Its construction was

approved by a Portuguese Episcopate conference, held in Fátima on 20 April 1940, as a plea

to God to prevent Portugal from entering World War II. However, the

idea had originated on a visit by the Cardinal Patriarch of Lisbon to

Rio de Janeiro in 1934, soon after the inauguration of the statue of Christ

the

Redeemer in

1931. In 1968,

Salazar suffered a brain haemorrhage. Most sources maintain that it

occurred when he fell from a chair in his summer house. In February

2009 though, there were anonymous witnesses who confessed, after some

research about Salazar's most well-kept secrets, that he had fallen in

a bathtub instead of from a chair.

There

was a heated conflict between his personal physician, Eduardo Coelho,

who realized an immediate operation was necessary and the first

surgeon consulted who delayed doing anything. Finally another surgeon

was found to do the operation. In any event, Salazar's incapacity

forced President Américo

Thomaz to replace him with Marcelo

Caetano on

September 27, 1968. It is believed that to his dying day Salazar

thought that he was still Prime Minister of Portugal, although this has

been disputed. He died in Lisbon on July 27, 1970. Tens of

thousands paid their last respects at the funeral and the Requiem

Mass that took

place at the Jerónimos

Monastery and at the passage of the special train that carried the

coffin to his hometown of Vimieiro near Santa Comba Dão, where

he was buried according to his wishes in his native soil, in a plain

ordinary grave. As a symbolic display of his views of Portugal and the

colonial empire, there is well-known footage of several members of the "Mocidade

Portuguesa," of both African and European ethnicity, paying homage

at his funeral.

After

Salazar's

death, his Estado

Novo regime

persisted under the direction of one of his longtime aides, Marcelo

Caetano. Despite tentative overtures towards an opening of the

regime, Caetano balked at ending the colonial war, notwithstanding the

condemnation of most of the international community. Eventually the Estado Novo fell in April 25, 1974,

after the Carnation

Revolution. Some factions, including Álvaro

Cunhal's PCP,

unsuccessfully

tried to turn the country into a totalitarian communist state. The retreat from the colonies and the acceptance of its independence terms which would

create newly-independent communist states in 1975 (most notably the People's

Republic

of Angola and

the People's

Republic

of Mozambique) prompted a mass exodus of Portuguese

citizens from Portugal's African territories (mostly from Portuguese Angola and Mozambique), creating over a million

destitute Portuguese refugees — the retornados.