<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Claude Elwood Shannon, 1916

- Poet Juhan Liiv, 1864

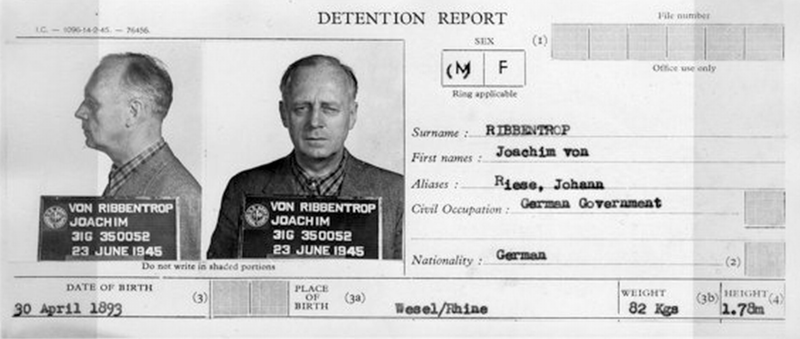

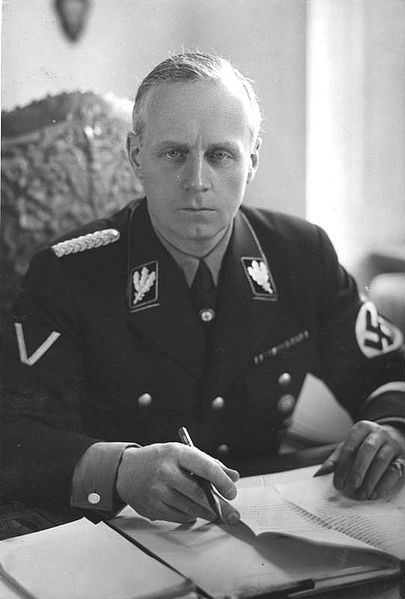

- Minister of Foreign Affairs Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop, 1893

PAGE SPONSOR

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was Foreign Minister of Germany from 1938 until 1945. He was later hanged for war crimes after the Nuremberg Trials.

Ribbentrop was born in Wesel, Rhenish Prussia, the son of Richard Ulrich Friedrich Joachim Ribbentrop, a career army officer, and his wife Johanne Sophie Hertwig. Ribbentrop was educated irregularly at private schools in Germany and Switzerland. His father was cashiered from the Imperial German Army in 1908, following a series of disparaging remarks he had made about the alleged homosexuality of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and the Ribbentrop family were often short of money. Fluent in both French and English, young Ribbentrop lived at various times in Grenoble, France, and London, before traveling to Canada in 1910. He worked for the Molsons Bank on Stanley Street in Montreal and then for the engineering firm M.P. and J.T. Davis on the reconstruction of the Quebec Bridge. He was also employed by the National Transcontinental Railway, which constructed a line from Moncton to Winnipeg. He worked as a journalist in New York City and Boston and then rested to recover from tuberculosis in Germany. He returned to Canada and set up a small business in Ottawa importing German wine and champagne. In 1914, he competed for Ottawa's famous Minto ice-skating team, participating in the Ellis Memorial Trophy tournament in Boston in February.

When World

War

I began,

Ribbentrop left Canada. He sailed from Hoboken,

New

Jersey, on 15

August 1914 on the Holland-America ship The Potsdam, bound

for Rotterdam. He then returned home and

enlisted in the 125th Hussar Regiment. He served

first on the Eastern Front, but was later transferred to the Western

Front. He earned a commission and

was awarded the Iron

Cross. In 1918 1st Lieutenant Ribbentrop was stationed in Istanbul as a staff officer. During

his

time in Turkey,

he

became friends with another staff officer named Franz

von

Papen.

In 1919

Ribbentrop met Anna Elisabeth Henkell, known as Annelies to her friends, daughter of a wealthy champagne producer

from

Wiesbaden. They married on 5 July 1920, and Ribbentrop travelled

across Europe as a wine salesman. He and his wife would have

five children:

Rudolf

von

Ribbentrop (born

11 May 1921, in Wiesbaden),

married

in 1960 Ilse-Marie Freiin von Münchhausen (1914 – 2010);

Bettina

von

Ribbentrop (born

20 July 1922, in Berlin);

Ursula

von

Ribbentrop (born

29 December 1932, in Berlin);

Adolf

von

Ribbentrop (born 2 September 1935, in Berlin), married first to Marion von Strempel and

later to Maria de Mercedes Christiane Josefine Thekla Walpurga Barbara

Gräfin und Edle Herrin von und zu Eltz genannt Faust von Stromberg

(born 27 November 1951 at Eltville),

and

had two sons from each marriage; Barthold

Henkell

von Ribbentrop (born

19

December 1940, in Berlin), married to Brigitte von Trotha, the

parents of Sebastian von Ribbentrop

(born 3 February 1971), married on 12 May 2001 at Fuschl to Elisabethe/Isabelle

Freiin Schuler von Senden (born 6 July 1975 in Munich). Annelies

von Ribbentrop was often described as being a Lady

Macbeth-type who dominated her husband. Ribbentrop persuaded his

aunt Gertrud von Ribbentrop to adopt him on 15 May 1925, which allowed

him to add the aristocratic von to his name. During the Weimar

Republic era,

Ribbentrop was apolitical and displayed no anti-Semitic prejudices. As a wealthy partner in the

Henckel-Trocken champagne firm, Ribbentrop did business with Jewish

bankers, and organized the Impegroma Importing Company ("Import und

Export großer Marken") with Jewish financing.

In 1928,

Ribbentrop was introduced to Hitler as a man who "gets the same price

for German champagne as others get for French champagne" as well as a

businessman with foreign connections. He joined the National

Socialist

German Workers' Party on

1

May 1932 at the urging of his wife, who herself joined the NSDAP at

the same time. In January 1933, there was

a complex set of intrigues which saw Franz

von

Papen and

various friends of the President Paul

von

Hindenburg negotiating with Hitler to oust the Chancellor,

General Kurt

von

Schleicher. The end

result of these talks was the appointment of Hitler as Chancellor on 30

January 1933. Ribbentrop, who was both a Nazi Party member and an old

friend of von Papen, facilitated the negotiations by arranging for von

Papen and Hitler to meet secretly at his house in Berlin. This

assistance endeared Ribbentrop to Hitler. Because Ribbentrop was a

latecomer to the Nazi Party, the Alte

Kämpfer (Old

Fighters) of the party disliked him. The British historian

Laurence Rees described Ribbentrop as "...the Nazi almost all the other

leading Nazis hated" Typical of this hatred for

Ribbentrop was the diary entry

of Joseph

Goebbels: "Von Ribbentrop bought his name, he married his money,

and he swindled his way into office". To

compensate

for this, Ribbentrop became a fanatical Nazi, almost to the

point of becoming a caricature of a Nazi brought to life. In

particular, Ribbentrop became a vociferous anti-Semite.

He became German dictator Adolf Hitler's favourite foreign policy adviser, partly by dint of his knowledge of the world outside Germany, but mostly by means of shameless flattery and sycophancy. The professional diplomats of the elite Auswärtiges Amt (Foreign Office) told Hitler the truth about what was happening abroad in the early years of Nazi Germany; Ribbentrop told Hitler what he wanted Hitler to hear. One German diplomat, Herbert Richter, in an interview later recalled "Ribbentrop didn't understand anything about foreign policy. His sole wish was to please Hitler". In particular, Ribbentrop acquired the habit of listening carefully to what Hitler was saying, memorizing pet ideas of the Führer, and then later presenting Hitler's ideas as his own — a practice that much impressed Hitler as proving Ribbentrop was an ideal National Socialist diplomat. To assist with this, Ribbentrop always questioned those who had lunch with Hitler about what he had said, thereby allowing Ribbentrop at his next meeting with Hitler to present Hitler's ideas as his own. Ribbentrop quickly learned that Hitler always favored the most radical solution to any problem, and accordingly tended his advice in that direction. As one of Ribbentrop's aides, the SS man Reinhard Spitzy, recalled:

"When

Hitler said 'Grey', Ribbentrop said 'Black, black, black'. He always

said it three times more, and he was always more radical. I listened to

what Hitler said one day when Ribbentrop wasn't present: 'With

Ribbentrop it is so easy, he is always so radical. Meanwhile, all the

other people I have, they come here, they have problems, they are

afraid, they think we should take care and then I have to blow them up,

to get strong. And Ribbentrop was blowing up the whole day and I had to

do nothing. I had to break - much better!'" Ribbentrop

in

turn was a great admirer of Hitler. Ribbentrop was emotionally

dependent on Hitler's favor to the extent that he suffered from psychosomatic illnesses if Hitler was unhappy with him. In 1933 he was given the

title of SS-Standartenführer.

For

a time, Ribbentrop was friendly with the Reichsführer-SS Heinrich

Himmler, but ultimately the two became enemies mostly because the

SS insisted upon the right to conduct its own foreign policy

independent of Ribbentrop. Ribbentrop

began

his work as an unofficial diplomat in the summer of 1933 with a

series of visits to Paris. Using the intermediary of Fernand de

Brinon, Ribbentrop was able to meet the French Premier Édouard

Daladier in

September 1933. Ribbentrop

tried

hard to set up a secret summit between Daladier and Hitler, only

to be told by Daladier that the idea of a secret Franco-German summit

was unacceptable as it was inevitable that the French press would

discover the secret summit. When Ribbentrop persisted

in trying to set up a secret Daladier-Hitler meeting, Daladier told him

that "I live under a regime which does not allow me to move as freely

as Herr Hitler" with Ribbentrop completely missing Daladier's sarcasm. In November 1933,

Ribbentrop was able to arrange an interview between de Brinon, who was

writing for the Le

Matin newspaper

and Hitler, during which Hitler stressed what he claimed to be his love

of peace and his friendship towards France. In

November 1933, Ribbentrop made his first visit to London as an

unofficial diplomat when he was able to use an old associate from his

wine-selling days, the British whisky tycoon Ernest Tennant, to set up

meetings with the Prime Minister Ramsay

MacDonald, the Lord President Stanley

Baldwin and Foreign

Secretary Sir John

Simon. Nothing of any substance

emerged from these talks. Up to the time of his

appointment as German Foreign Minister, Ribbentrop aggressively

competed with the Auswärtiges

Amt (Foreign

Office) and sought to undercut the current Foreign Minister, Baron Konstantin

von

Neurath, at every turn. Initially, Neurath held his

rival in contempt, regarding anyone whose written German, to say

nothing of his English and French, was full of atrocious spelling and

grammatical mistakes to be unworthy of attention. Speaking of views of Prince

Bernard von Bülow, the State Secretary at the Auswärtiges Amt between 1930 – 1936 and the

nephew of the former Chancellor Bernhard

von

Bülow, one contemporary recalled that "Bülow could

not regard as a serious competitor a man who had no formal training in

diplomacy, who could not write a report in correct German, who did not

listen carefully enough to the remarks of foreign statesmen to

interpret them correctly, and who insisted upon seeing possibilities of

alliance [with Britain] where none existed". In March

1934, Ribbentrop visited France, where he met the Foreign Minister Louis

Barthou. During the meeting,

Ribbentrop suggested that Barthou meet with Hitler at once to sign a

Franco-German non-aggression pact. In response to German

violations of Part V of the Treaty of Versailles, which had disarmed

Germany, there had been several calls in France in 1933 for a

preventive war before German rearmament was complete. Ribbentrop’s

intention in proposing a 10 year Franco-German non-aggression pact was

to buy time for completing German rearmament by removing preventive war

as a French policy option. Barthou was forced to explain to Ribbentrop

that he was not a dictator, and since France was a democracy, he would

have to meet and discuss with the Cabinet before opening talks on a non-aggression pact. Barthou commented to

Ribbentrop about Hitler that "The words are of peace, but the actions

are of war". The Barthou-Ribbentrop meeting further estranged Neurath, who was infuriated that Ribbentrop

met Barthou without bothering to inform the Auswärtiges Amt beforehand. In a report to President

von Hindenburg, Neurath wrote: "Such

agents have often been active in the past and especially since the war.

Their success and hence their usefulness is generally slight. In

particular, it has been shown by experience that their connections are

quickly used up. As soon as they meet with government members, the

question concerning the official or semi-official nature of their

instructions or mission is soon raised. Responsible statesmen naturally

refuse to commit themselves to agents without responsibility. With

that, the activity of these intermediaries in most cases comes to an

end. Thus, in London recently Baldwin referred Herr Ribbentrop to Sir

John Simon as the Minister responsible for questions of foreign policy.

M. Barthou has now complained to Ambassador Köster about the

manner of bringing in Herr Ribbentrop. From secret reports, it appears

that M. Barthou was far from pleased with the visit and therefore

treated Herr von Ribbentrop in a decidedly sarcastic manner...". In April

1934, Ribbentrop was named Special Commissioner for Disarmament by Hitler, which made him

part of the same Auswärtiges Amt that was the center of his

competition with Neurath. After Ribbentrop's

appointment as Special Commissioner, Neurath informed Erich Kordt, the diplomat assigned to Ribbentrop as his aide, not to

correct any of Ribbentrop's spelling mistakes. Ribbentrop was given the

office of Special Commissioner in large part because of doubts created

in foreign capitals over just what precisely was his status as a

diplomat. In his capacity as Special Commissioner, Ribbentrop

frequently visited London, Paris and Rome. In his early years, Hitler's

aim in foreign affairs was to persuade the world that he wished to

reduce military

spending by making

idealistic but very vague offers of disarmament (in the 1930s, the term

disarmament was used to describe arms-limitation agreements). At the same time, the Germans always resisted making concrete proposals for arms limitation,

and they went ahead with increased military spending on the grounds

that other powers would not take up German offers of arms limitation. Ribbentrop's task was to

ensure that the world was convinced that Germany sincerely wanted an

arms-limitation treaty while also ensuring that such a treaty never

actually emerged. In the first part of his

assignment, Ribbentrop was partly successful, but in the second part he

more than fulfilled Hitler's expectations. On 17

April 1934, French Foreign Minister Louis

Barthou issued the

so-called "Barthou note" terminating French involvement in the World Disarmament

Conference on

the grounds that Germany had been negotiating in bad faith, declaring

henceforth that France would look after its own security. The aggressive tone of the

"Barthou note" led to concerns on the part of Hitler that the next

meeting of the Bureau of Disarmament of the League

of

Nations would

see the French asking for sanctions against Germany for violating Part

V of the Treaty of

Versailles. Ribbentrop volunteered to

stop the rumored sanctions, and visited London and Rome. During his visits,

Ribbentrop met with Simon and Benito

Mussolini, and asked them to postpone the next meeting of the

Bureau of Disarmament, in exchange for which Ribbentrop offered nothing

in return other than promises of better relations with Berlin. Despite Ribbentrop's

efforts, the meeting went ahead as scheduled, but since no sanctions

were sought against Germany, this led to Ribbentrop claiming success

(in fact, Ribbentrop's efforts had nothing to do with the lack of

sanctions). As Special Commissioner,

Ribbentrop was allowed to see all diplomatic correspondence relating to

the subject of disarmament, which Ribbentrop refused to share with

Neurath or von Bülow. Due to Ribbentrop's perceived success in stopping sanctions being applied against Germany,

Hitler ordered that Ribbentrop be allowed to see all diplomatic

correspondence that was not "Marked for the Foreign Minister" or "For

the Secretary of State". Ribbentrop used this

privilege to go through the incoming diplomatic messages, snatching

certain messages, taking them to Hitler and having a reply written

without Neurath or Bülow being informed first. In August

1934, Ribbentrop founded an organisation linked to the Nazi Party

called the Büro

Ribbentrop (later

renamed the Dienststelle Ribbentrop) that functioned as an

alternative foreign ministry. The Dienststelle Ribbentrop,

which

had its offices located directly across from the Auswärtiges Amt building on the

Wilhelmstrasse in Berlin, had in its membership a collection of Hitlerjugend alumni, dissatisfied businessmen, former reporters, and ambitious Nazi

Party members, all

of whom tried to conduct a foreign policy independent of and often

contrary to the Auswärtiges

Amt. Though the Dienststelle Ribbentrop concerned itself with

German foreign relations with every part of the world, a special

emphasis was put on Anglo-German

relations, as Ribbentrop knew an alliance with Britain was a

project specially favored by Hitler. In

the 1920s, Hitler had

written that the principle goal of a future National Socialist foreign

policy would be the "the destruction of Russia with the help of England”.

As

such, Ribbentrop worked hard during his early diplomatic career to

realize Hitler’s dream of an anti-Soviet Anglo-German alliance.

Ribbentrop made frequent trips to Britain, and upon his return he

always reported to Hitler that the great mass of the British people

longed for an alliance with Germany. In November 1934,

Ribbentrop visited Britain where he met with George

Bernard

Shaw, Sir Austen

Chamberlain, Lord

Cecil, and Lord

Lothian. On the basis of remarks

from Lord Lothian praising the natural friendship between Germany and

Britain, Ribbentrop informed Hitler that all elements of British

society wished for closer ties with Germany, a report which delighted

Hitler, causing him to remark that Ribbentrop was the only person who

told him "the truth about the world abroad". Since the diplomats of the Auswärtiges Amt were not so sunny in their

appraisal of the prospects of an Anglo-German alliance, Ribbentrop's

influence with Hitler increased. Hitler

later

stated: "In 1933-34 the reports of the Foreign Office [Auswärtiges

Amt] were miserable. They always had the same quintessence: that we

ought to do nothing". By contrast, Hitler found

that the reports of the extremely aggressive and energetic Ribbentrop

were more in tune with what Hitler wanted to hear, leading to the

influence of the former being much increased at the expense of the Auswärtiges Amt. Moreover, since Hitler regarded the diplomats of the Auswärtiges

Amt as a collection of stodgy reactionaries out of touch with the

spirit of "New Germany", the personality of Ribbentrop, with his

disregard for diplomatic niceties, was in line with what Hitler felt

should be the relentless dynamism of a revolutionary regime. Ribbentrop

was

rewarded by Hitler by being made Reich Minister

Ambassador-Plenipotentiary at Large (1935 – 1936). Ribbentrop then made

numerous trips all over Europe, where he constantly presented various

German proposals meant to upset the international order such as his

1935 offer to Belgium that Germany would renounce its claim to the Eupen-Malmedy region

in

exchange for a Belgian renunciation of the 1920 alliance with France. In 1935, Ribbentrop was

able to arrange for a series of much publicized visits of World War I

veterans to Britain, France and Germany. Ribbentrop persuaded the British

Legion (the leading

veterans' group in Britain) and many of the French veterans' groups to

send delegations to Germany to meet German veterans as the best way of

promoting peace. At the same time,

Ribbentrop arranged for members of the Frontkämpferbund,

the

official German World War I veterans' group, to make visits to

Britain and France to meet veterans there. The visits of the veterans

with the attendant promises of "never again" with regards to war did

much to improve the image of the "New Germany" in Britain and France.

In July 1935, the visit of the British Legion delegation to Germany was

headed by Brigadier Sir Francis Featherstone-Godley. Prince

of

Wales (who was

the patron of the Legion), made a much publicized speech at the

Legion's annual conference in June 1935 stating he could think of no

better group of men than those of the Legion to visit and carry the

message of peace to Germany, and stated that he hoped that Britain and

Germany would never fight again. Throughout

his

time as Ambassador

at

Large, Ribbentrop refused to share any information about his

activities to the Auswärtiges Amt, who were very much

frustrated by Ribbentrop's non-cooperative attitude. In his capacity as

Ambassador-Plenipotentiary at Large, he negotiated the Anglo-German

Naval

Agreement (A.G.N.A.)

in

1935 and the Anti-Comintern

Pact in 1936. In

regards to the former, Neurath did not think the A.G.N.A. was possible;

to discredit his rival, he appointed Ribbentrop head of the delegation

sent to London in June 1935 to negotiate it. Once the talks began,

Ribbentrop, who possessed a certain elan and sense of audacity, issued

Sir John

Simon an ultimatum. He informed Simon that if

Germany's terms were not accepted in their entirety, the German

delegation would go home. Simon was angry with this

demand and walked out of the talks under the grounds that "It is not

usual to make such conditions at the beginning of negotiations". Much to everyone's

surprise, the next day the British accepted Ribbentrop's demands and

the A.G.N.A. was signed in London on 18 June 1935 by Ribbentrop and Sir Samuel

Hoare, the new British Foreign Secretary. This

diplomatic success did much to increase Ribbentrop's prestige with

Hitler. Hitler called 18 June, the day the A.G.N.A. was signed, “the

happiest day in my life” as he believed it marked the beginning of an

Anglo-German alliance, and ordered celebrations throughout Germany to

mark the event. Immediately

after

the signing of the A.G.N.A., Ribbentrop followed up with the next

step that was intended to create the Anglo-German alliance, namely the Gleichschaltung (co-ordination) of all

societies demanding the restoration of the former German colonies in

Africa into the Reichskolonialbund (Reich Colonial League)

under General Franz

Ritter

von Epp. General

von

Epp in turn reported to Ribbentrop, who used the noisy agitation of

the Reichskolonialbund to press for Germany's

“inalienable” right to her former African colonies. It was the joint idea of

Hitler and Ribbentrop that demanding colonial restoration would

pressure the British into making an alliance with the Reich on German terms. However, there was a

certain difference of opinion between Ribbentrop and Hitler in that

Ribbentrop sincerely wished to recover the former German African

colonies, whereas for Hitler, colonial demands were just a negotiating

tactic that would see Germany “renounce” her colonial claims in

exchange for a British alliance. In the

fall of 1935, Ribbentrop founded two "friendship societies" in Berlin,

namely the Deutsch-Englische

Gesellschaft for

relations

with Britain and the Deutsch-Französische

Gesellscaft for

relations with France. Both of the societies were

closely linked to two other societies Ribbentrop had helped to create,

the Comité

France-Allemagne headed

by Fernand

de

Brinon and the Anglo-German

Fellowship headed

at first by Ernest Tennant. Through his work with these

societies, Ribbentrop worked to trying to convert elites in France and

Britain into following a pro-German line. In

February 1936, when Hitler asked Neurath and Ribbentrop for their

advice about whatever to remilitarize the Rhineland, Ribbentrop urged unilateral remilitarization at once.

Ribbentrop

went so far as to tell Hitler that if France attacked

Germany because of the Rhineland, then Britain would come to Germany’s

aid and attack France.

Much

to Neurath’s discomfort, Hitler found Ribbentrop’s advice more

appealing than his own. During a

visit to London in April 1936, Ribbentrop met the Welsh political fixer

and former civil servant Thomas

Jones. As Sir Robert

Vansittart, the Permanent Undersecretary at the British Foreign

Office, was showing little interest in Ribbentrop's proposals for an

Anglo-German alliance, Ribbentrop switched his efforts to cultivating

Jones. As Jones was now in

retirement (though he retained some influence through his friendship

with the Prime Minister Stanley

Baldwin), he was much impressed by Ribbentrop's efforts to

cultivate him. Through Jones, Ribbentrop

was able to meet Baldwin. Jones and Ribbentrop spent

much of the spring and summer of 1936 attempting to set up a

Hitler-Baldwin meeting only to be frustrated by Baldwin's dislike of

travelling. At a meeting in May 1936,

Jones told Baldwin that it was "a mistake to underestimate von

Ribbentrop's influence and write him down as an ass because he does not

adopt orthodox procedure. At the very least he is a reliable telephone

from Hitler and the likelihood is that he is much more". Despite Jones's pleas,

Baldwin was unmoved in refusing to make a trip to Germany. The Anti-Comintern

Pact of November

1936 marked an important change in German foreign policy. The Auswärtiges Amt had traditionally favoured

a policy of friendship with China, one that Neurath very much believed

in following. Ribbentrop was opposed to

the pro-China orientation of the Auswärtiges Amt and instead favoured an

alliance with Japan. To this end, Ribbentrop

often worked closely with General Hiroshi

Ōshima, who served first as the Japanese military attaché,

and then as Ambassador in Berlin in strengthening German-Japanese ties,

in spite of furious opposition from the Wehrmacht and the Auswärtiges Amt,

who

preferred closer Sino-German ties. The origins of the

Anti-Comintern Pact went back to the summer and fall of 1935, when in

an effort to square the circle between seeking a rapprochement with Japan and Germany’s

traditional alliance with China, Ribbentrop, together with General

Ōshima, devised the idea of an anti-Communist alliance as a way of

binding China, Japan and Germany together. However,

when

the Chinese made it clear that they had no interest in such an

alliance (especially given that the Japanese regarded Chinese adhesion

to the proposed pact as a way of subordinating China to Japan), both

Neurath and the War Minister Field

Marshal Werner

von

Blomberg persuaded Hitler to shelve the proposed treaty in

November 1935, lest it damage Germany's good relations with China. Ribbentrop for his part,

who valued Japanese friendship far more than Chinese friendship, argued

that Germany and Japan should sign the pact, even without Chinese

participation. By November 1936, a revival

of interest in a German-Japanese pact in both Tokyo and Berlin led to

the signing of the Anti-Comintern Pact in Berlin. When the Pact was signed,

invitations were sent out for Italy, China, Britain and Poland to

adhere; of the invited powers, only the Italians were ultimately to

sign the Anti-Comintern Pact. The Anti-Comintern Pact

marked the beginning of the shift on Germany's part from China's ally

to Japan's ally. During

the same period, Ribbentrop often visited France to try to influence,

though not very successfully, French politicians into adopting a

pro-German foreign policy. Ribbentrop enjoyed more

success in the United Kingdom, where he was able to persuade an

impressive array of British high society to visit Hitler in Germany. That Ribbentrop possessed

the power to set up meetings with Hitler and represented himself as

Hitler's personal envoy made him for a time a much courted figure in

Britain. The most notable guest

Ribbentrop brought to Hitler was the former Prime Minister David

Lloyd

George in

1936. Hitler's

British

guests were a mélange of aristocratic Germanophiles such

as Lord

Londonderry, professional pacifists such as George

Lansbury and Lord

Allen, retired politicians, ex-generals, fascists such as Admiral Barry

Domvile and Sir Oswald

Mosley, journalists such as Lord

Lothian and G. Ward

Price, academics such as the historian Philip Conwell-Evans, and

various businessmen like the newspaper magnate Lord

Rothermere and the

merchant banker Lord

Mount

Temple. Very few of these people

were actual decision-makers in the British government, such as

Cabinet-level politicians or high-ranking bureaucrats. Neither

Hitler nor

Ribbentrop understood very well that when people like Lloyd George,

Londonderry, Lansbury, Mount Temple, Allen, Lothian or Rothermere

declared that they favoured closer Anglo-German ties, they were

speaking as private citizens, not on behalf of Whitehall. As a German

diplomat, Truetzschler von Falkenstein complained after the war that

"Ribbentrop, having had contact with only a small group in England –

representatives of the so-called two hundred families – did not know

the great mass of the English people. The England with which he had

hoped to collaborate was the England of this select group, since he

believed that its members controlled Britain". Another German diplomat

commented that Ribbentrop had the strange idea to "conduct

international relations through aristocrats". Yet another German diplomat

noted that, "He [Ribbentrop] did not have the capacity to form an

overview; to see things in perspective. In England, for example, he

relied upon people like Conwell-Evans who had no real influence". Earlier, speaking of

Ribbentrop's activities and of the views of his British friends, Leopold

von

Hoesch, the German Ambassador in London from 1932–36, warned

that Berlin should "...not pay any attention to the Londonderrys and

Lothians, who in no way represented any important section of British

opinion". In August

1936, the German government appointed Ribbentrop Ambassador to Britain with orders to negotiate

the Anglo-German alliance that Hitler had predicted in Mein

Kampf. Ribbentrop arrived to take

up his position in October 1936. The two month delay between Ribbentrop's appointment and his arrival in London was due to the

fracas caused by the death of the Auswärtiges

Amt's State Secretary Prince von Bülow in July 1936.

Ribbentrop immediately suggested to Hitler that he succeed Bülow

as State Secretary. Neurath informed Hitler

that he would rather resign than have Ribbentrop as State Secretary and

proceeded to appoint his son-in-law Hans Georg von Mackensen to that

office. Hitler, for his part, had

been highly impressed by Neurath's skillful efforts at defusing the

crisis caused by remilitarization of the Rhineland in March 1936, and moreover

felt that Ribbentrop's talents better suited him to serving as Ambassador than as State Secretary. Ribbentrop,

who

would have much preferred to be State Secretary than Ambassador,

spent the next two months attempting to persuade Hitler to give him the

former office rather than the latter before reluctantly leaving for

Britain in October 1936. Before

leaving to take up his post in London, Ribbentrop was commissioned by

Hitler: “Ribbentrop...get

Britain

to join the Anti-Comintern Pact, that is what I want most of

all. I have sent you as the best man I’ve got. Do what you can... But

if in future all our efforts are still in vain, fair enough, then I’m

ready for war as well. I would regret it very much, but if it has to

be, there it is. But I think it would be a short war and the moment it

is over, I will then be ready at any time to offer the British an

honorable peace acceptable to both sides. However, I would then demand

that Britain join the Anti-Comintern Pact or perhaps some other pact.

But get on with it, Ribbentrop, you have the trumps in your hand, play

them well. I'm ready at any time for an air pact as well. Do your best.

I will follow your efforts with interest”. The vain,

arrogant, and tactless Ribbentrop was not the man for such a mission,

but it is doubtful that even a more skilled diplomat could have

fulfilled Hitler's dream of a grand Anglo-German alliance. His time in London was

marked by an endless series of social gaffes and blunders that worsened

his already poor relations with the British Foreign Office (Punch referred

to

him as Von Brickendrop and the Wandering Aryan due to his frequent

trips back to Germany.) Upon arriving in Britain on

October 26, 1936, Ribbentrop created a storm in the British press by

reading the following statement: "Germany

wants

to be friends with Great Britain and, I think, the British people

also wish for German friendship. The Führer is

convinced that there is

only one real danger to Europe and to the British Empire as well, and

that is the spreading further of communism, this most terrible of all

diseases - terrible because people generally seem to realize its danger

only when it is too late. A closer collaboration in this sense between

our two countries is not only important but a vital necessity in the

common struggle for the upholding of our civilization and our culture". The Daily

Telegraph newspaper

commented

that it was regrettable that the new German ambassador could

offer no better basis for improved Anglo-German relations beyond a

common hatred for a third country. To help with his move to

London, and with the design of the new German Embassy Ribbentrop had

built (the existing Embassy was deemed insufficiently grand for

Ribbentrop), Ribbentrop hired a Berlin interior decorator named Martin

Luther. Upon the recommendation of

his wife, Ribbentrop hired Luther to work for the Dienststelle Ribbentrop. Luther proved to be a

master intriguer, and became Ribbentrop's favorite hatchet man. Besides

working to achieve Hitler's dream of an Anglo-German alliance against

the Soviet Union, Ribbentrop served as the German delegate for the Non-Intervention

Committee for the Spanish

Civil

War in London. Since Germany was in fact

intervening in the civil war in Spain, Ribbentrop's purpose at the

Non-Intervention Committee was to frustrate and sabotage the workings

of the committee as much as possible. Ribbentrop

did

not understand the King's limited role in government as he thought

King Edward

VIII could decide

British foreign policy. He convinced Hitler that he

had Edward's support; but this, like his belief that he had impressed

British society, was a tragic delusion. Ribbentrop often woefully

misunderstood both British politics and society. During the abdication

crisis

of December 1936, Ribbentrop reported to Berlin that the

reason the crisis had occurred was an anti-German

Jewish-Masonic-reactionary conspiracy to depose Edward (whom Ribbentrop

represented as a staunch friend of Germany), and that civil war would

soon break out in Britain between supporters of the King and supporters

of the Prime Minister, Stanley

Baldwin. Ribbentrop's statements

about the abdication crisis causing a civil war were greeted with much

incredulity by those British people who heard them. This led to a false sense

of confidence about British intentions with which he unwittingly

deceived his Führer. Ribbentrop's

time

as Ambassador was notable as he threw the German

Embassy into a

total state of chaos due to his erratic personality. Ribbentrop's aide,

the SS man Reinhard Spitzy, described a typical day working for

Ribbentrop as: "He

[Ribbentrop] rose, muttering bad-temperedly...Dressed in his pyjamas,

he received the junior secretaries and press attachés in his

bathroom...He scolded, threatened, gesticulated with his razor and

shouted at his valet...As he took his bath, he ordered people to be

summoned from Berlin, accepted and cancelled, appointed and dismissed,

and dictated through the door to a nervous stenographer...He cursed

people in their absence, calling them saboteurs and communists... It was

my task to put his calls through; his valet stood within splashing

distance holding a white telephone... Ribbentrop believed only ministers

ranked above him: everyone else, including his ambassadorial

colleagues, had to be kept waiting on the line. Sometimes they did not

share this view and rang off. The outburst of rage which ensured was

directed against me.. Ribbentrop's

habit

of summoning tailors from the best British firms, making them

wait for hours and then sending them away without seeing him with

instructions to return the next day, only to repeat the process, did

immense damage to his reputation in British high society. As a result of Ribbentrop's

abusive behavior towards the tailors of London, the tailors retaliated

by telling all of their other well-off clients what an impossible man

Ribbentrop was to deal with. In an interview, Spitzy

stated "He [Ribbentrop] behaved very stupidly and very pompously and

the British don't like pompous people". In the same interview,

Spitzy called Ribbentrop "pompous, conceited and not too intelligent",

and stated he was an utterly insufferable man to work for. In addition, the fact that

Ribbentrop chose to spend as little time as possible in London in order

to stay close to Hitler irritated the British Foreign Office immensely,

as Ribbentrop's frequent absences prevented the handling of many

routine diplomatic matters. As Ribbentrop progressively

starting alienating more and more people in Britain, Hermann

Göring warned

Hitler that Ribbentrop was a "stupid ass". Hitler dismissed

Göring's concerns by saying "But after all, he knows quite a lot

of important people in England", leading Göring to reply "Mein

Führer, that may be right, but the bad thing is, they know

him". In

February 1937, Ribbentrop committed a notable social gaffe by

unexpectably greeting King George

VI with a "Heil

Hitler!" Nazi salute which nearly knocked the King over as he

walked forward to shake Ribbentrop's hand. Ribbentrop further

compounded the damage to his image and caused a minor crisis in

Anglo-German relations by insisting that hencefoward all German

diplomats were to greet heads of state with the "German greeting", who

were in turn to return the fascist salute. The

crisis

was resolved when Neurath pointed out to Hitler that under

Ribbentrop's rules, if the Soviet Ambassador were to give the Communist

clenched fist salute, then Hitler would be obliged to return it. As a result of Neurath's

advice, Hitler disavowed Ribbentrop over his demands that King George

receive and give the "German greeting". In his

dealings with the British government, most of Ribbentrop's time was

spent either demanding that Britain sign the Anti-Comintern

Pact or that London

return the former German colonies in Africa. Other than his fruitless

meetings with the British Foreign Secretary Sir Anthony Eden, who always refused on behalf of his government Ribbentrop's

demands about the former colonies or the Anti-Comintern Pact, Ribbentrop spent most of his time as Ambassador courting what

Ribbentrop called the “men of influence” as the best way of bringing about an Anglo-German alliance. Ribbentrop

had developed

the notion that the British aristocracy comprised some sort of secret

society that ruled from behind the scenes, and if he could befriend

enough members of Britain's “secret government”, then he could bring

about an alliance with his country. Almost all of the initially

favorable reports Ribbentrop provided to Berlin about the prospects of

an Anglo-German alliance were based on friendly remarks about the “New

Germany” from various British aristocrats like Lord Londonderry and

Lord Lothian; the rather cool reception that Ribbentrop received from

British Cabinet ministers and senior bureaucrats did not make much of

an impression on him at first. In 1935, Sir Eric

Phipps, the British

Ambassador

to Germany, complained to London about Ribbentrop's

British associates in the Anglo-German

Fellowship, that they created "false German hopes as in regards to

British friendship and caused a reaction against it in England, where

public opinion is very naturally hostile to the Nazi regime and its

methods". In September 1937, the

British Consul in Munich,

writing

about the group Ribbentrop had brought to the Nuremberg Party

Rally, reported that there were some "serious persons of standing among

them" and that an equal number of Ribbentrop's British contingent were

"eccentrics and few, if any, could be called representatives of serious

English thought, either political or social, while they most certainly

lacked any political or social influence in England". In June 1937, when Lord

Mount

Temple, the Chairman of the Anglo-German Fellowship, asked to

see the British Prime Minister Neville

Chamberlain after

meeting Hitler in a visit arranged by Ribbentrop, Robert

Vansittart, the British Foreign Office's Undersecretary wrote a

memo stating that: "The

P.M. [Prime Minister] should certainly not see Lord Mount Temple – nor

should the S[ecretary] of S[tate]. We really must put a stop to this

eternal butting in of amateurs – and Lord Mount Temple is a

particularly silly one. These activities – which are practically

confided to Germany – render impossible the task of diplomacy. Lord

Londonderry goes to Berlin; Lord Lothian goes to Berlin; Mr. Lansbury

goes to Berlin; and now Lord Mount Temple goes. They all want

interviews with the S of S, and two at least have had them. This flow

is quite unfair to the service and Sir E. Phipps rightly complained of

these ambulant amateurs. So did Sir N. Henderson in advance, and

rightly, for Lord Lothian's last visit is being mischievously and

unintelligently misused, particularly at the Imperial Conference. The

proper course for any ambulant amateur is to be seen by someone less

important than Ministers. If there is anything worthwhile in their

remarks – there never is, for, of course, we have much better

information than this naïf propaganda stuff – we can report it to

the S of S. But a stage has now been reached where the service is

entitled to at least this amount of protection. These superficial

people are always gulled into the lines of least resistance – vide Lord

Lothian – and we then have the ungrateful but necessary task of

pointing out the snags and appearing obstructive. It is quite unfair

and should cease”. After

Vansittart's memo, members of the Anglo-German Fellowship ceased to see

Cabinet ministers after going on Ribbentrop-arranged trips to Germany.

One of the "men of influence" Ribbentrop attempted to win over was Winston

Churchill (who in fact in 1937 possessed little influence), who

during a 1937 meeting told him that though most people in Britain hated

communism, neither the British government or British people wanted an

anti-Soviet alliance with Germany nor would they accept a pro quid quo in which Britain would abandon Europe to Germany in exchange for German support for

maintaining the British Empire. Ribbentrop then told

Churchill if Britain would not ally herself with Germany, then the

Germans would have no other choice, but to destroy the British Empire,

leading Churchill to reply that the last time the Germans tried that,

it was the German Empire that ended up being destroyed. In

February 1937, prior to a meeting with the Lord

Privy

Seal, Lord

Halifax, Ribbentrop suggested to Hitler that Germany together with

Italy and Japan began a worldwide propaganda campaign with the aim of

forcing Britain to return the former German colonies in Africa. Hitler turned down this

idea of Ribbentrop’s, but nonetheless during his meeting with Lord

Halifax, Ribbentrop spent much of the meeting demanding that Britain

sign an alliance with Germany and return the former German colonies. The German historian Klaus

Hildebrand noted

that as early as the Ribbentrop–Halifax meeting the differing foreign

policy views of Hitler and Ribbentrop were starting to emerge with

Ribbentrop more interested in restoring the pre-1914 German Imperium in Africa than conquest of

Eastern Europe. Following the lead of Andreas

Hillgruber, who argued that Hitler had a stufenplan (stage by stage plan) for

world conquest, Hildebrand argued that Ribbentrop may not have fully

understood what Hitler’s stufenplan was, or alternatively in

pressing so hard for colonial restoration was trying to score a

personal success that might improve his standing with Hitler. In March 1937, Ribbentrop

attracted much adverse comment in the British press when he gave a

speech at the Leipzig

Trade

Fair in Leipzig,

where

he declared that German economic prosperity would be satisfied

either "through the restoration of the former German colonial

possessions, or by means of the German people's own strength”. The

implied threat that if

colonial restoration did not occur, then the Germans would take back by

force their former colonies attracted a large deal of hostile

commentary on the inappropriateness of an Ambassador threatening his

host country in such a manner. His

aggressive and overbearing manner towards everyone except his wife and

Hitler meant that to know him was to dislike him. His negotiating style, a

strange mix of bullying bluster and icy coldness coupled with lengthy

monologues praising Hitler, alienated many. The American historian Gordon

A.

Craig once

observed that of all the voluminous memoir literature of the diplomatic

scene of 1930s Europe, there are only two positive references to

Ribbentrop. Of the two references,

General Leo

Geyr

von Schweppenburg, the German military attaché in

London, commented that Ribbentrop had been a brave soldier in World

War

I, while the wife of the Italian Ambassador to Germany,

Elisabetta Cerruti, called Ribbentrop "one of the most diverting of the

Nazis". In both cases the praise

was limited, with Cerruti going on to write that only in the Third

Reich was it possible for someone as superficial as Ribbentrop to rise

to be a minister of foreign affairs, while Geyr von Schweppenburg

called Ribbentrop an absolute disaster as Ambassador in London. The British historian/television producer Laurence Rees noted for his 1997 series The Nazis A Warning from

History that every

single person interviewed for the series who knew Ribbentrop expressed

a passionate hatred for him. One German diplomat,

Herbert Richter, called Ribbentrop "lazy and worthless" while another,

Manfred von Schröder, was quoted as saying Ribbentrop was "vain

and ambitious". Rees concluded that "No

other Nazi was so hated by his colleagues". In

November 1937, Ribbentrop was placed in a highly embarrassing situation

when his forceful advocacy of the return of the former German colonies

led to the British Foreign Secretary Anthony

Eden and the French

Foreign Minister Yvon

Delbos offering to open talks on returning the former German

colonies, in return for which the Germans would make binding

commitments to respect their borders in Central and Eastern Europe. Since Hitler was not really

interested in obtaining the former colonies, especially if the price

was a brake on expansion into Eastern Europe, Ribbentrop was forced to

turn down the Anglo-French offer that he had largely brought about. Immediately after turning

down the Anglo-French offer on colonial restoration, Ribbentrop for

reasons of pure malice ordered the Reichskolonialbund to increase the agitation

for the former German colonies, a move which exasperated both the

Foreign Office and Quai d'Orsay. Ribbentrop's

inability

to achieve the alliance that he had been sent out for

frustrated him, as he feared it could cost him Hitler's favour, and it

made him a bitter Anglophobe. As the Italian Foreign

Minister, Count Galeazzo

Ciano, noted in his diary in late 1937, Ribbentrop had come to hate

Britain with all the “fury of a woman scorned”. Ribbentrop, and Hitler for

that matter, never understood that British foreign policy aimed at the appeasement of Germany, not an alliance. When

Ribbentrop travelled to Rome in November 1937 to oversee Italy's

adhesion to the Anti-Comintern Pact, he made clear to his hosts that

the pact was really directed against Britain. As Count Ciano noted in his

diary, the Anti-Comintern Pact was "anti-Communist in theory, but in

fact unmistakably anti-British". Believing himself to be in

a state of disgrace with Hitler over his failure to achieve the British

alliance, Ribbentrop spent December 1937 in a state of depression, and

together with his wife, wrote two lengthy documents for Hitler

denouncing Britain. In the first of his two

reports to Hitler, which was presented on 2 January 1938, Ribbentrop

stated that "England is our most dangerous enemy". In

the same report,

Ribbentrop advised Hitler to abandon the idea of a British alliance,

and instead embrace the idea of an alliance of Germany, Japan and

Italy, who would destroy the British

Empire. Ribbentrop wrote: "I have

worked for many years for friendship with England and nothing would

make me happier than if it could be achieved. When I asked the Führer to send me to London, I was

sceptical whether it would work. However, in view of Edward VIII, a

final attempt seemed appropriate. Today I no longer believe in an

understanding. England does not want a powerful Germany nearby which

would pose a permanent threat to the islands". Ribbentrop

wrote

in his "Memorandum for the Führer"

that

"a change in the status quo in the East to Germany's advantage can

only be accomplished by force", and that the best way to achieve this

change was to build a global anti-British alliance system. Besides converting the

Anti-Comintern Pact into an anti-British military alliance, Ribbentrop

argued that German foreign policy should work to "furthermore, winning

over all states whose interests conform directly or indirectly to ours". By

the

last statement, Ribbentrop clearly implied that the Soviet Union

should be included in the anti-British alliance system he had proposed. Ribbentrop

ended his memo

with the advice to Hitler that: "Henceforth - regardless of what

tactical

interludes of conciliation may be attempted with regard to us - every

day that our political calculations are not actuated by the fundamental

idea that England is our most dangerous enemy would be a gain to our

enemies". While the

Ribbentrops were in Britain, his son, Rudolf

von

Ribbentrop, attended Westminster

School in London. Peter

Ustinov was Rudolf's schoolmate at this time, as related in his

autobiography Dear Me (1971). Ustinov is also

supposed to have clandestinely leaked Rudolf's presence at his school to The

Times. The result of this was the prompt withdrawal of the

younger Ribbentrop from the school as a precautionary measure for his

safety, as well as for security of his father's mission in London. Ribbentrop's

time

in London was also marked by scandal. It was believed by many

members of the British upper classes that he was having an affair with Wallis

Simpson, the wife of British businessman Edward Simpson and the

mistress of King

Edward

VIII. According to files recently declassified by the United

States Federal

Bureau

of Investigation, Mrs. Simpson was believed to be a regular

guest at Ribbentrop's social gatherings at the German Embassy in London

where it was thought the two struck up a romantic relationship. It was believed by the

Americans at the time that Ribbentrop was said to have used Simpson's

access to the King to funnel important information about the British to

the German government. Supposedly,

Simpson

was paid by the Germans for this information and was happy to

continue the relationship as long as she received payment. The FBI took

the matter seriously enough to advise President Roosevelt of their findings; he once

commented to a confidante that Simpson "played around... with the

Ribbentrop set." The truth

of the matter is still very much in doubt. Simpson, who later married

the former king – he had abdicated to marry her – and was

known in later life as the Duchess of Windsor, noted in her book The Heart Has Its Reasons that she met Ribbentrop on

only two occasions and had no personal relationship with him.

On

5

November 1937, the conference between the Reich’s top

military-foreign policy leadership and Hitler recorded in the so-called Hossbach Memorandum occurred.

At

the conference, Hitler stated that it was the time for war, or, more

accurately, wars, as what Hitler envisioned were a series of localized

wars in Central and Eastern Europe in the near future. Hitler argued

that because these wars were necessary to provide Germany with Lebensraum, autarky and the arms

race with France and Britain made it imperative to act

before the Western powers developed an insurmountable lead in the arms

race. Of those invited to the

conference, objections arose from Neurath, the War Minister Field

Marshal Werner

von

Blomberg, and the Army Commander in Chief, General Werner

von

Fritsch that any German aggression in Eastern

Europe was bound to

trigger a war with France because of the French alliance system in

Eastern Europe, the so-called cordon

sanitaire, and if a Franco-German war broke out, then Britain

was almost certain to intervene rather than risk the prospect of

France’s defeat. Moreover,

it

was objected that Hitler's assumption that Britain and France would

just ignore the projected wars because they had started their

re-armament later than Germany was flawed. Accordingly, Fritsch,

Blomberg and Neurath advised Hitler to wait until Germany had more time

to re-arm before pursuing a high-risk strategy of localized wars that

was likely to trigger a general war before Germany was ready (none of

those present at the conference had any moral objections to Hitler’s

strategy, with which they were in basic agreement; only the question of

timing divided them). Hitler was most displeased

with the criticism of his intentions, and in early 1938 asserted his

control of the military-foreign policy apparatus through the Blomberg-Fritsch

Affair, the abolition of the War Ministry and its replacement by the OKW,

and

finally by sacking Neurath as Foreign Minister on 4 February 1938. In the opinion of the

official German history of World War II, from early 1938 Hitler was not

carrying out a foreign policy that had carried a high risk of war, but

was carrying out a foreign policy aiming at war. Ribbentrop was chosen as

Neurath’s successor as Hitler judged the former would be a more willing

instrument to realize Hitler’s foreign policy than the latter. On 4

February 1938, Ribbentrop succeeded Baron Konstantin

von

Neurath as

Foreign Minister. Ribbentrop's appointment was generally taken at the

time and since as indicating that German foreign policy was moving in a

more radical direction. In contrast to Neurath's less bellicose and

cautious nature, Ribbentrop unequivocally supported war in 1938-39. In May 1938 Benito

Mussolini commented

after meeting Ribbentrop that: "Ribbentrop

belongs

to the category of Germans who are a disaster for their

country. He talks about making war right and left, without naming an

enemy or defining an objective". Under

Ribbentrop's influence, Hitler grew increasingly anti-British, through

he never fully embraced Ribbentrop's anti-British foreign policy programme, which as the German historian Andreas

Hillgruber noted

was the "very opposite" of Hitler's foreign programme which saw an

anti-Soviet alliance with Britain as the best course.

Ribbentrop's

time as Foreign Minister can be divided into three

periods. In the first, from 1938 – 39, he tried to persuade other states

to align themselves with Germany for the coming war. In the second from

1939 – 43, Ribbentrop attempted to persuade other states to enter the war

on Germany's side or at least maintain pro-German neutrality. In the

final phase from 1943 – 45, he had the task of trying to keep Germany's

allies from leaving her side. During the course of all three periods,

Ribbentrop met frequently with leaders and diplomats from Italy, Japan, Romania,

Spain, Bulgaria,

and

Hungary. During all this time, Ribbentrop feuded with various other

Nazi leaders; at one point in August 1939 an armed clash took place

between supporters of Ribbentrop and those of Propaganda Minister Joseph

Goebbels over the

control of a radio station

in Berlin that was

meant to broadcast German propaganda abroad (Goebbels claimed exclusive

control of all propaganda both at home and abroad whereas Ribbentrop

asserted a claim to monopolize all German propaganda abroad). As Foreign Minister,

Ribbentrop was highly concerned with counteracting the damage that he

himself inflicted on the influence of the Auswärtiges Amt. Friedrich Gaus, the chief

of the Legal Division of the Auswärtiges

Amt testified at

the Nuremberg war crimes trials that: "He

[Ribbentrop] used to say, that everything the Foreign Office lost in

the way of terrain under Neurath he wanted to win back and, with all

his passion, he fought for this aim in a manner which can only be

understood by somebody who actually saw it". Gaus went

on to testify that "My main activity was 90 per cent concerned with

competency conflicts". Moreover, as time went by,

Ribbentrop started to oust the old diplomats from their senior

positions in the Auswärtiges

Amt and replaced

them with men from the Dienststelle. As

early as 1938, 32% of the offices in the Foreign Ministry were held

by men who previously served in the Dienststelle. Ribbentrop was widely

disliked by the old diplomats in Auswärtiges

Amt. Herbert

von

Dirksen who served as Ribbentrop's successor as German Ambassador in London in 1938 - 1939 described Ribbentrop as "an

unwholesome, half-comical figure". Dirksen was to later write that he at first hoped that now that Ribbentrop was Foreign Minister

this would mean the end of the Dienststelle "for no man can intrigue against himself. That Ribbentrop was able to perform even this miracle

only came home to me much later". Many of the people

Ribbentrop appointed to head German embassies, especially the "amateur"

diplomats from the Dienststelle were grossly incompetent,

thus limiting the effectiveness of the Auswärtiges Amt.

One

of

Ribbentrop's first acts as Foreign Minister was to achieve a total volte-face in Germany's Far Eastern

policies. Ribbentrop was instrumental in February 1938 persuading

Hitler to recognize the Japanese puppet

state of Manchukuo and to renounce German

claims upon her former colonies in the Pacific, which were now held by

Japan. By April 1938, Ribbentrop

had ended all German arms shipments to China and had all of the German

Army officers

serving with the Kuomintang government of Chiang

Kai-shek recalled

(with the threat that the families of the officers in China would be

sent to concentration camps if the officers did not return to Germany

immediately). In return, the Germans

received little thanks from the Japanese, who refused to allow any new

German businesses to be set up in the part of China they had occupied,

and continued with their policy of attempting to exclude all existing

German (together with all other Western) businesses from

Japanese-occupied China. At the same time, the

ending of the informal Sino-German alliance led Chiang to terminate all

of the concessions and contracts held by German companies in Kuomintang

China.

As

Foreign

Minister, Ribbentrop was noted for his virulent Anglophobia and anti-Semitism.

Although

he was almost lackey-like

in

Hitler's presence, he could be boorish when he was alone. At a

meeting between Ribbentrop, Hitler and Henderson on 3 March 1938 during

which Henderson offered on behalf of his government a proposal for an

international consortium to rule much of Africa, in which Germany would

play a leading role in exchange for which Germany would agree not to

change its borders through violence, the British offer was flatly

refused by Hitler, who had no real interest in colonies in Africa, and

was more interested in the idea of Lebensraum or expansionism, in

Eastern Europe. At the same meeting,

Ribbentrop stated that the British government secretly controlled the

British press, and hence could silence at any moment all press

criticism of the Nazi regime; the fact that the British government had

not done so was proof of British malevolence towards Germany. After

the

meeting, Henderson reported to the British Foreign Secretary Lord

Halifax about a

private conversation he had with Ribbentrop: "He [Ribbentrop] talked so

much... about what Great Britain should do that I warned at last that

you [Lord Halifax] would be expecting rather to hear what Germany would

be prepared to do. His reply was: "What can we do? We have nothing to

give". Ribbentrop loathed Neville

Chamberlain, and viewed his appeasement policy as some sort of

British scheme to block Germany from her rightful place in the world. Chamberlain for his part

after meeting Ribbentrop in February 1938 wrote in a letter to his

sister that he found Ribbentrop to be "so stupid, so shallow, so

self-centered and so self-satisfied, so totally devoid of intellectual

capacity, that he never seems to take in what is said to him". In

the

aftermath of Munich, Hitler was in a violently anti-British mood caused

in part over his rage over being “cheated” out of the war to

“annihilate” Czechoslovakia that he very much wanted to have in 1938,

and in part by his realization that Britain would neither ally herself

nor stand aside in regards to Germany’s ambitions to dominate Europe. As a consequence, after

Munich, Britain was considered to be the main enemy of the Reich, and as a

result, the influence of ardently Anglophobic Ribbentrop

correspondingly rose with Hitler. Starting in the fall of

1938, Ribbentrop attempted to convert the Anti-Comintern Pact into an

anti-British military alliance, without much success. Much to Ribbentrop's

intense disappointment, the Japanese were more interested in 1938-39 in

fighting the Soviets and the Chinese rather than fighting the British. The Japanese were willing

to see the Anti-Comintern Pact converted into a military alliance, but

only against the Soviet Union. Unknown to Ribbentrop, the differences

in opinion during the winter of 1938-39 between Japan and Germany about

whether to convert the Anti-Comintern Pact into an anti-British or an

anti-Soviet military alliance were known to the Kremlin thanks to the

fact that the Soviets had broken the Japanese diplomatic codes and

through the spy ring in Tokyo headed by Richard

Sorge. As part

of the anti-British course, it was deemed necessary in Germany to have

Poland as either a satellite

state or otherwise

neutralized. The Germans believed this necessary on both strategic

grounds as a way of securing the Reich’s

eastern

flank and on economic grounds as a way of evading the effects

of a British blockade. Starting in October 1938,

Ribbentrop during several meetings with the Polish Ambassador to Germany Józef

Lipski and the

Polish Foreign Minister Colonel Józef

Beck expressed his

wishes that Poland agree to the return of the Free

City

of Danzig (modern Gdańsk,

Poland)

to the Reich,

allow for “extra-territorial” highways across the Polish

Corridor to East

Prussia, and most importantly, sign the Anti-Comintern

Pact (the last

gesture was generally understood as placing Poland within the German

sphere of influence). At a meeting with Lipski in

October 1938, Ribbentrop stated that he wanted eine Gesamtlösung (total settlement) between

Germany and Poland with Poland being reduced to a subordinate state to

the Reich within

the Anti-Comintern

Pact. In

October-November 1938, Ribbentrop together with the Italian Foreign

Minister Count Galeazzo Ciano, delegations led by the Czecho-Slovak foreign minister František

Chvalkovský, and the Hungarian foreign minister Count Kálmán

Kánya conducted negotiations in Vienna that resulted in the First

Vienna

Award over

the fate of the eastern part of Czecho-Slovakia (as

Czechoslovakia

had been renamed in October 1938). During the talks, a

clash of interests arose between the Italians who favored seeing

Hungary restored to pre-Trianon borders, whereas the

Germans, who were disappointed over Hungary’s lukewarm attitude towards

attacking Czechoslovakia in September 1938, tended to favor

Czecho-Slovakia. At the same time, Ribbentrop, who was trying to enlist

Italy into his anti-British alliance, was not inclined towards pushing

the Italians too hard, and the resulting Vienna Award was a compromise

between the rival German and Italian claims to influence in Eastern

Europe. In the

aftermath of the Kristallnacht pogrom in November 1938,

the U.S. government formally protested and withdrew Hugh Wilson, the

American Ambassador in Berlin in protest. In retaliation, Ribbentrop

withdrew the German Ambassador in Washington, Hans-Heinrich

Dieckhoff,

and delivered a counter-protest note accusing the U.S.

government of being secretly controlled by Jewish plutocrats. Right up

until 1941, German-American relations were conducted by chargé

d'affaires as neither government ever sent back their ambassadors. In

regards to the anti-Semitic policies, Ribbentrop emerged as one of the

leading hardliners, and refused to even consider the idea (which some

of the other Nazi leaders were open to, through only on pragmatic

grounds as a way of encouraging Jewish emigration) that German Jews be

allowed to bring their personal possessions with them when they left

Germany. At a meeting in Paris with

the French Foreign Minister, Georges

Bonnet in December

1938, when Bonnet asked if it was possible for immigrating German Jews to

bring their personal belongings with them, Ribbentrop replied: "The

Jews in Germany were without exception pickpockets, murderers and

thieves. The property they possessed had been acquired illegally. The

German government had therefore decided to assimilate them with the

criminal elements of the population. The property which they had

acquired illegally would be taken from them. They would be forced to

live in districts frequented by the criminal classes. They would be

under police observation like other criminals. They would be forced to

report to the police as other criminals were obligated to do. The

German government could not help it if some of these criminals escaped

to other countries which seemed so anxious to have them. It was not,

however, willing for them to take the property, which had resulted from

their illegal operations with them".

On 6

December 1938 Ribbentrop visited Paris, where he and the French foreign

minister Georges

Bonnet signed a

grand-sounding but largely meaningless Declaration of Franco-German

Friendship. Ribbentrop was later to

claim that Bonnet told him that France recognized Eastern

Europe as being

within Germany's exclusive sphere of influence. Later in December 1938,

Ribbentrop, during a meeting with the Polish Foreign Minister Colonel

Beck at Berchtesgaden, attempted to win his acceptance of the German

proposals by promising him German support for Polish annexation of the Ukraine,

only

to be told that Poland had no interest in seeing either Danzig

return to the Reich,

or

in annexing the Ukraine. On

6 February 1939, in

response to a speech given by Bonnet before the Chamber of Deputies,

underlining French commitments in Eastern Europe, Ribbentrop offered a

formal protest to Robert Coulondre, the French Ambassador in Berlin,

arguing that because of Bonnet’s alleged statement of 6 December 1938,

that “France’s commitments in Eastern Europe” were now “off limits”. Partly

for economic reasons, and partly out of fury over being “cheated” out

of war in 1938, in early 1939, Hitler decided to commence the

destruction of the rump state of Czecho-Slovakia (as Czechoslovakia had been

renamed in October 1938). Ribbentrop played an

important role in setting the crisis that was to result in the end of

Czecho-Slovakia in motion by ordering German diplomats in Bratislava to contact Father Jozef

Tiso, the Premier of the Slovak regional government, and pressuring

him to declare independence from Prague. When Tiso proved reluctant to do so under the grounds that the autonomy

that had existed since October 1938 was sufficient for him, and to

completely sever links with the Czechs would leave Slovakia open to

being annexed by Hungary, Ribbentrop had the German Embassy in Budapest contact the Regent, Admiral Miklós

Horthy.

Admiral Horthy was advised that the Germans might be open

to having more of Hungary restored to former borders, and that the

Hungarians should best start concentrating troops on their northern

border at once if they were serious about changing the frontiers. Upon

hearing of the Hungarian mobilization, Tiso was presented with the

choice of either declaring independence with the understanding that the

new state would be in the German sphere of influence, or seeing all of

Slovakia absorbed into Hungary. When as a result, Tiso had the Slovak

regional government issue a declaration of independence on 14 March

1939, the ensuing crisis in Czech-Slovak relations was used as a

pretext to summon the Czecho-Slovak President Emil

Hácha to

Berlin over his “failure” to keep order in his country. On the night of

14–15 March 1939, Ribbentrop played a key role in the German annexation

of the Czech part of Czecho-Slovakia by bullying the Czechoslovak President Hácha into

transforming his country into a German protectorate at a meeting in the Reich

Chancellery in

Berlin. On 15 March 1939, German troops occupied the Czech area of

Czecho-Slovakia, which then became the Reich Protectorate of Bohemia and

Moravia. On March 20, 1939 Ribbentrop summorned the Lithuanian

Foreign Minister Juozas

Urbšys to Berlin

and informed him that if a Lithuanian plenipoteiary did not arrive at

once to negotiate turning over the Memelland to Germany the Luffwaffe

would raze Kaunas to the ground.

As

a result of Ribbentrop's ultimatum on March 23rd, the

Lithuanians argeed to return Memel (modern Klaipėda, Lithuania) to

Germany. In March

1939, Ribbentrop assigned the largely ethnic Ukrainian Sub-Carpathian

Ruthenia region of

Czecho-Slovakia, which had just proclaimed its independence as the

Republic of Carpatho-Ukraine to Hungary, which then

proceeded to annex it after a short war. The significance of this

lies in that there had been many fears in the Soviet Union in the 1930s

that the Germans would use Ukrainian nationalism as a

tool for breaking up the Soviet Union. The establishment of an

autonomous Ukrainian region in Czecho-Slovakia in October 1938 had

promoted a major Soviet media campaign against its existence under the

grounds that this was part of a Western plot to support separatism in

the Soviet

Ukraine. By allowing the Hungarians

to destroy Europe’s only Ukrainian state, Ribbentrop had signified that

Germany was not interested (at least for the moment) in sponsoring

Ukrainian nationalism. This in turn helped to

improve German-Soviet relations by demonstrating that German foreign

policy was now primarily anti-Western rather than anti-Soviet. Initially,

the

German hope was to transform Poland into a satellite state, but by

March 1939 the German demands had been rejected by the Poles three

times, which led Hitler to decide with enthusiastic support from

Ribbentrop upon the destruction of Poland as the main German foreign

policy goal of 1939. On March 21, 1939

Ribbentrop presented a set of demands to the Polish Ambassador Józef Lipski about Poland

allowing the Free City of Danzig to return to Germany in such violent

and extreme language that it led to the Poles to fear their country was

on the verge of an immediate German attack.

Ribbentrop

had used such extreme language that it led to the Poles

ordering partial Mobilization and placing their armed

forces on the highest state of alert on March 23rd, 1939.

In

a protest note at Ribbentrop’s behaviour, Colonel Beck reminded the

German Foreign Minister that Poland was an independent country and was

not some sort of German protectorate whom Ribbentrop could bully at will.

Though

the Germans were not planning an attack on Poland in March

1939, Ribbentrop's bullying behavior towards the Poles destroyed

whatever faint chance there was of Poland allowing Danzig to return to

Germany. From

March 1939, Ribbentrop had become the leading advocate within the

German government of reaching an understanding with the Soviet

Union as the best

way of pursuing both the short-term anti-Polish, and long-term

anti-British foreign policy goals. Ribbentrop's efforts to

convert the Anti-Comintern Pact into an anti-British alliance met with

considerable hostility from the Japanese over the course of the winter

of 1938-39, but with the Italians Ribbentrop enjoyed some apparent

success. Because of Japanese opposition to participation in an

anti-British alliance, Ribbentrop decided to settle for a bilateral

German-Italian anti-British treaty. Ribbentrop's efforts were crowned

with success with the signing of the Pact

of

Steel in May

1939, through this was accomplished only by falsely assuring Mussolini

that there would be no war for the next three years. In April

1939, Ribbentrop received intelligence that Britain and Turkey were negotiating an

alliance intended to keep Germany out of the Balkans. Ribbentrop appointed Franz

von

Papen as the

German Ambassador in Ankara with instructions to win

Turkey to an alliance with Germany. Instead of focusing on

talking to the Turks, Ribbentrop and Papen became entangled in a feud