<Back to Index>

- Inventor Elisha Gray, 1835

- Sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, 1834

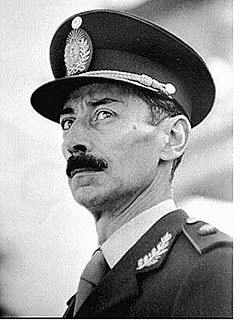

- Dictator of Argentina Jorge Rafael Videla Redondo, 1925

PAGE SPONSOR

Jorge Rafael Videla Redondo (born August 2, 1925 in Mercedes, Buenos Aires) was the 43rd President of Argentina from 1976 to 1981. He came to power in a coup d'état that deposed Isabel Martínez de Perón. After the return to democracy, he was prosecuted for large scale human rights abuses and crimes against humanity that took place under his rule, including kidnappings or forced disappearance, widespread torture and extrajudicial murder of activists, political opponents (either real, suspected or alleged), as well as their families, at secret concentration camps. The accusations also included the theft of many babies born during the captivity of their mothers at the illegal detention centres. He was under house arrest until October 10, 2008, when he was sent to a military prison. On July 5, 2010, Videla took full responsibility for his army's actions during his rule. "I accept the responsibility as the highest military authority during the internal war. My subordinates followed my orders," he told an Argentine court.

After serving as Director of the National Military College (Colegio Militar de la Nación) and after almost two months as Chief of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (Estado Mayor Conjunto) of the Argentine Armed Forces, Brigade General Jorge Videla was named Commander-in-Chief by President Isabel Perón in 1975. Perón, former Vice-President to her husband Juan Perón, had come to the presidency following his death. Her authoritarian administration was unpopular and ineffectual. Videla headed a military coup which deposed her on March 24, 1976. A military junta was formed, made up of himself, representing the Army, Admiral Emilio Massera representing the Navy, and Brigadier General Orlando Ramón Agosti representing the Air Force. Two days after the coup, Videla formally assumed the post of President of Argentina.

The military junta took power during a period of extreme instability, with terrorist attacks from the Marxist groups ERP, the Montoneros, FAL, FAR and FAP, who had turned underground after Juan Perón's death in July 1974, from one side and violent right wing kidnappings, tortures, and assassinations from the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance, led by José López Rega, Perón's Minister of Social Welfare, and other death squads on the other side. The members of the junta took advantage of this to justify the coup, by naming the administration "National Reorganization Process". In all, 293 servicemen and policemen were killed in left wing terrorist incidents between 1975 and 1976. Lieutenant General Jorge Videla himself narrowly escaped three Montoneros assassination attempts between February 1976 and April 1977. The Argentine military government arrested, detained, tortured, and killed suspected terrorists and political opponents. As a result, human rights violations became commonplace. According to estimates, at least 9,000 and up to about 30,000 Argentinians were subject to forced disappearance (desaparecidos) and most probably killed; many were illegally detained and tortured, and others went into exile. The Asemblea por los Derechos Humanos (APDH or Assembly for Human Rights) believes that 12,261 people were killed or disappeared during the "National Reorganization Process". Politically, all legislative power was concentrated in the hands of Videla's nine man junta, and every single important position in the national government was filled with loyal military officers. The junta banned labor unions and strikes, abolished the judiciary, and effectively suspended most civil liberties. Despite the abuses, Videla's regime received support from the Argentine Roman Catholic Church and local media.

During Videla's regime, Argentina refused the binding Report and decision of the Court of Arbitration over the Beagle conflict at the southern tip of South America and started the Operation Soberania in order to invade the islands. In 1978, however, Pope John Paul II opened a mediation process. His representative, Antonio Samoré, successfully prevented full-scale war. The conflict was not completely resolved until 1984 with the Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1984 between Chile and Argentina (Tratado de Paz y Amistad). Chilean sovereignty over the islands is now undisputed.

Videla largely left economic policies in the hands of Minister José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz. During his tenure, the foreign debt increased

fourfold, and disparities between the upper and lower classes became

much more pronounced as compared to the populist days of Perón. One

of Videla's greatest challenges was his image abroad. He attributed

criticism over human rights to an anti-Argentine campaign. On 30 April 1977, Azucena Villaflor,

along with 13 other women, started demonstrations on the Plaza de Mayo,

in front of the Casa Rosada presidential palace, demanding to be told

the whereabouts of their disappeared children; they would become known

as las madres de la Plaza de Mayo. During a human rights investigation in September 1979, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights denounced his government, citing many disappearances and instances of abuse. Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, leader of the Peace and Justice Service (Servicio Paz y Justicia) organization, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1980 for exposing many of Argentina's human rights violations to the world at large.

At first, the United States government was willing to maintain normal diplomatic relations with Argentina, though transcripts show U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and

the US ambassador to Argentina in conflict over how the new regime

should be treated, with Kissinger preferring to remain friendly based on anti-Communist interests despite the human rights abuses. This changed in 1977 with the inauguration of President Jimmy Carter, who implemented a strict stance against human rights abuses even when dealing with friendly governments. Argentina – United States relations remained lukewarm at best until Ronald Reagan became president in 1981. His administration sought the assistance of the Argentine intelligence services in training the Contras for guerrilla warfare against the new Sandinista government in Nicaragua. Because of this, Videla maintained a relatively friendly relationship with the US under the Reagan administration, though the junta later fell out of favor with the US over the Falklands War after Videla had stepped down. Videla relinquished power to Roberto Viola on March 29, 1981. Democracy was restored in 1983, and Videla was put on trial and found guilty. He was sentenced to life imprisonment and was discharged from the military in 1985. The tribunal found Videla guilty of numerous homicides, kidnapping, torture, and many other crimes. Videla was imprisoned for only five years. In 1990, President Carlos Menem pardoned Videla

together with many other former members of the military regime. Menem

cited the need to get over past conflicts as his main reason. Videla

briefly returned to prison in 1998 when a judge found him guilty of the

kidnapping of babies during the Dirty War, including the child of the desaparecida Silvia Quintela and the disappearances of the commanders of the People's Revolutionary Army (ERP), Mario Roberto Santucho and Benito Urteaga. Videla spent 38 days in the old part of the Caseros Prison, and was later transferred to house arrest due to health issues. Following the election of President Néstor Kirchner in

2003, there has been a widespread effort in Argentina to show the

illegality of Videla's rule. The government no longer recognizes Videla

as having been a legal president of the country, and his portrait has

been removed from the military school. There have also been many legal

prosecutions of officials associated with the crimes of the regime. On September 6, 2006, Judge Norberto Oyarbide ruled that the pardon granted by Menem was unconstitutional, opening up the possibility of a trial. On April 25, 2007, a federal court struck down his presidential pardon and restored his human rights abuse convictions. On

July 2, 2010, Videla was put on trial for human rights violations

relating to the deaths of 31 prisoners who died under his rule.