<Back to Index>

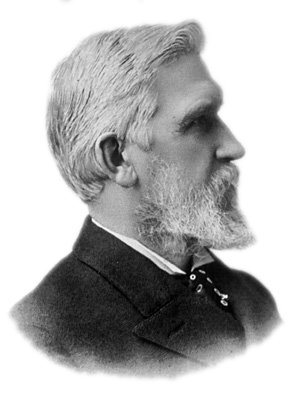

- Inventor Elisha Gray, 1835

- Sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, 1834

- Dictator of Argentina Jorge Rafael Videla Redondo, 1925

PAGE SPONSOR

Elisha Gray (August 2, 1835 – January 21, 1901) was an American electrical engineer who co-founded the Western Electric Manufacturing Company. Gray is best known for his development of a telephone prototype in 1876 in Highland Park, Illinois, and is considered by some writers to be the true inventor of the variable resistance telephone, despite losing out to Alexander Graham Bell for the telephone patent. Gray is also considered to be the father of the modern music synthesizer, and was awarded over 70 patents for his inventions. Born into a Quaker family in Barnesville, Ohio, Gray was brought up on a farm. He spent several years at Oberlin College where

he experimented with electrical devices. Although Gray was not a

graduate of Oberlin College, he taught electricity and science at

Oberlin and built laboratory equipment for Oberlin science departments. In 1862 while at Oberlin, Gray met and married Delia Minerva Shepard. In 1865 Gray invented a self adjusting telegraph relay that automatically adapted to varying insulation of the telegraph line. In

1867 Gray received a patent for the self adjusting telegraph relay and

in later years he received patents for more than 70 other inventions. In

1869, Elisha Gray and his partner Enos M. Barton founded Gray &

Barton Co. in Cleveland, Ohio, to supply telegraph equipment to the giant Western Union Telegraph Company. The electrical distribution business was later spun off from Western Electric and organized into a separate company, Graybar Electric Company, Inc.. Barton had been employed by Western Union to examine and test new products. In 1870 financing for Gray & Barton Co. was arranged by General Anson Stager,

a superintendent of the Western Union Telegraph Company. Stager became

an active partner in Gray & Barton Co., which moved to Chicago.

Gray moved from Ohio to Highland Park near

Chicago and remained on the board of directors. But he gave up his

administrative position as chief engineer to focus on inventions that

could benefit the telegraph industry. Gray's inventions and patent

costs were financed by a dentist, Dr. Samuel S. White of Philadelphia,

who had made a fortune producing porcelain teeth. White wanted Gray to

focus on the acoustic telegraph

which promised huge profits to the exclusion of what appeared to be

unpromising competing inventions such as the telephone. It was White's

decision in 1876 to abandon Gray's caveat for the telephone. In

1870, Gray developed a needle annunciator for hotels and another for

elevators. He also developed a telegraph printer which had a typewriter keyboard and printed messages on paper tape. In 1872 Western Union, then financed by the Vanderbilts and J.P. Morgan, bought one-third of Gray and Barton Co. and changed the name to Western Electric Manufacturing Company of Chicago. Gray continued to invent for Western Electric. In

1874, Gray retired to do independent research and development. Gray

applied for a patent on a harmonic telegraph which consisted of

multi-tone transmitters, each tone being controlled by a separate

telegraph key. Gray gave several private demonstrations of this

invention in New York and Washington, D.C., in May and June 1874.

On July 27, 1875, Gray was granted patent 166,096 for "Electric Telegraph for Transmitting Musical Tones" (acoustic telegraphy). During

the weekend of February 12-14, 1876, before either caveat or

application had been filed in the patent office, Bell's lawyer learned

about the liquid transmitter idea in Gray's caveat that would be filed

early Monday morning February 14. Bell's

lawyer then added seven sentences describing the liquid transmitter and

a variable resistance claim to Bell's draft application. After the

lawyer's clerk recopied the draft as a finished patent application,

Bell's lawyer hand-delivered the finished application to the patent

office just before noon on Monday, a few hours after Gray's caveat was

delivered to the patent office by Gray's lawyer. Bell's lawyer

requested that Bell's application be immediately recorded and

hand-delivered to the examiner on Monday so that later Bell could claim

it had arrived first. Bell was in Boston at this time and was not aware

that his application had been filed in the US patent office. Five

days later, on February 19, Zenas Fisk Wilber, the patent examiner for

both Bell's application and Gray's caveat, noticed that Bell's

application claimed the same variable resistance feature described in

Gray's caveat. Wilber declared an interference that would delay Bell's application until Bell submitted proof, under the first to invent rules, that Bell had invented that feature before Gray. Bell's

lawyer telegraphed Bell, who was still in Boston, to come to Washington

DC. When Bell arrived on February 26, Bell visited his lawyers and then

visited examiner Wilber who told Bell that Gray's caveat showed a

liquid transmitter and asked Bell for proof that the liquid transmitter

idea (described in Bell's patent application as using mercury as the

liquid) was invented by Bell. Bell pointed to an application of Bell's

filed a year earlier where mercury was used in a circuit breaker. The

examiner accepted this argument, although mercury would not have worked

in a telephone transmitter. On March 3, Wilber approved Bell's

application and on March 7, 1876 patent 174,465 was published by the U.S. Patent Office. Bell

returned to Boston and resumed work on March 9, drawing a diagram in

his lab notebook of a water transmitter being used face down and very

similar to that shown in Gray's caveat." Bell

and Watson built and tested Gray's water transmitter design on 10 March

and successfully transmitted clear speech saying "Mr. Watson -- come

here -- I want to see you." Bell's notebooks did not become public until the 1990s. The

importance of Bell's test of Gray's water transmitter idea was it

proved that clear speech could be transmitted electrically. It was a

scientific experiment, not development of a commercial product. Prior

to that, Bell had only an unproven theory. Although

Gray had abandoned his caveat, Gray applied for a patent for the same

invention in late 1877. This put him in a second interference with

Bell's patents. The Patent Office determined

"while Gray was undoubtedly the first to conceive of and disclose the

[variable resistance] invention, as in his caveat of 14 February 1876,

his failure to take any action amounting to completion until others had

demonstrated the utility of the invention deprives him of the right to

have it considered." Gray

challenged Bell's patent anyway, and after two years of litigation,

Bell was awarded rights to the invention, and as a result, Bell is

credited as the inventor. In 1886, Wilber stated in a sworn affidavit that he was an alcoholic and deeply in debt to Bell's lawyer Marcellus Bailey with

whom Wilber had served in the Civil War. Wilber stated that, contrary

to Patent Office rules, he showed Bailey the caveat Gray had filed.

Wilber also stated that he showed the caveat to Bell and Bell gave him

$100. Bell testified that they only discussed the patent in general

terms, although in a letter to Gray, Bell admitted that he learned some

of the technical details. Bell's

patent was also disputed in 1888 by attorney Lysander Hill who accused

Wilber of allowing Bell or his lawyer Pollok to add a handwritten

margin note of 7 sentences to Bell's application that describe an

alternate design similar to Gray's liquid microphone design. However,

the marginal note was added only to Bell's earlier draft, not as a

marginal addition to his patent application that shows the 7 sentences

already present in a paragraph in Bell's patent application when it was

filed in the Patent Office on February 14, 1876. Bell testified that he

added those 7 sentences in the margin of an earlier draft of his

application "almost at the last moment before sending it off to

Washington" to his lawyers. Bell or his lawyer could not have added the

7 sentences to the application after it was filed in the Patent Office,

because then there would not have been any interference on February 19. Although Bell was accused, and is still accused, of stealing the telephone from Gray, Bell used Gray's water transmitter design only after Bell's patent was granted and only as a proof of concept scientific experiment to prove to his own satisfaction that intelligible "articulate speech" (Bell's words) could be electrically transmitted. Bell's assistant Thomas Watson testified that he tested all of the competing designs. After

March 1876, Bell and Watson focused on improving the electromagnetic

telephone and never used Gray's liquid transmitter in public

demonstrations or commercial use. When

Bell demonstrated his telephone at the Centennial Exhibition in June

1876, he used his improved electromagnetic transmitter, not Gray's

water transmitter. In 1887 Gray invented the "telautograph",

a device that could remotely transmit handwriting through telegraph

systems. Gray was granted several patents for these pioneer fax

machines, and the Gray National Telautograph Company was charted in

1888 and continued in business as The Telautograph Corporation for many

years; after a series of mergers it was finally absorbed by Xerox in

the 1990s. Gray's telautograph machines were used by banks for signing

documents at a distance and by the military for sending written

commands during gun tests when the deafening noise from the guns made

spoken orders on the telephone impractical. The machines were also used

at train stations for schedule changes. Gray displayed his telautograph invention in 1893 at the 1893 Columbian Exposition and

sold his share in the telautograph shortly after that. Gray was also

chairman of the International Congress of Electricians at the World's

Columbian Exposition of 1893. Gray conceived of a primitive closed circuit television system that he called the "telephote".

Pictures would be focused on an array of selenium cells and signals

from the selenium cells would be transmitted to a distant station on

separate wires. At the receiving end each wire would open or close a

shutter to recreate the image. In

1899 Gray moved to Boston where he continued inventing. One of his

projects was to develop an underwater signaling device to transmit

messages to ships. One such signaling device was tested on December 31,

1900. Three weeks later, on January 21, 1901, Gray died from a heart

attack in Newtonville, Massachusetts. As of 2006 no book-length biography has been written about the life of Elisha Gray. An Oberlin physics

department head named Dr. Lloyd W. Taylor began writing a Gray

biography, but the book was never finished because of Taylor's

accidental death in July 1948. Dr Taylor's unfinished manuscript is in

the College Archives at Oberlin College.

Because of Samuel White's opposition

to Gray working on the telephone, Gray did not tell anybody about his

new invention for transmitting voice sounds until Friday 11 February

1876 when Gray requested that his patent lawyer William D. Baldwin

prepare a "caveat" for filing at the US Patent Office. A caveat was like a provisional patent application with drawings and description but without claims. On the morning of Monday 14 February 1876,

Gray signed and had notarized the caveat that described a telephone

that used a liquid microphone. Baldwin then submitted the caveat to the

US Patent Office. That same morning a lawyer for Alexander Graham Bell submitted

Bell's patent application. Which application arrived first is hotly

disputed, although the most recent evidence suggest Gray's caveat

arrived a few hours before Bell's application. Bell's

lawyers in Washington, DC, had been waiting with Bell's patent

application for months, under instructions not to file it in the USA

until it had been filed in Britain first. (At the time, Britain would

only issue patents on discoveries not previously patented elsewhere.)