<Back to Index>

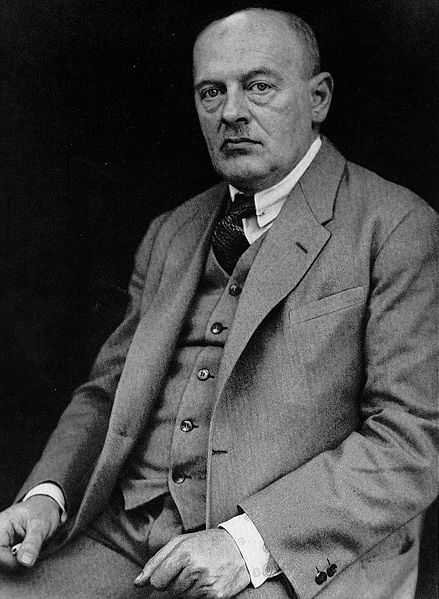

- Philosopher Max Scheler, 1874

- Author Dorothy Parker, 1893

- King of Serbia Milan I Obrenović, 1854

PAGE SPONSOR

Max Scheler (August 22, 1874, Munich – May 19, 1928, Frankfurt am Main) was a German philosopher known for his work in phenomenology, ethics, and philosophical anthropology. Scheler developed further the philosophical method of the founder of phenomenology, Edmund Husserl, and was called by José Ortega y Gasset "the first man of the philosophical paradise." After his demise in 1928, Heidegger affirmed, with Ortega y Gasset, that all philosophers of the century were indebted to Scheler and praised him as "the strongest philosophical force in modern Germany, nay, in contemporary Europe and in contemporary philosophy as such." In 1954, Karol Wojtyla, later Pope John Paul II, defended his doctoral thesis on "An Evaluation of the Possibility of Constructing a Christian Ethics on the Basis of the System of Max Scheler."

Max Scheler was born in Munich, Germany, August 22, 1874, to a Lutheran father and an Orthodox Jewish mother. As an adolescent, he turned to Catholicism, likely because of its conception of love, although he became increasingly non-committal around 1921. After 1921 he disassociated himself in public from Catholicism.

Scheler studied medicine in Munich and Berlin, both philosophy and sociology under Wilhelm Dilthey and Georg Simmel in 1895. He received his doctorate in 1897 and his associate professorship (habilitation thesis) in 1899 at the University of Jena, where his advisor was Rudolf Eucken, and where he became Privatdozent in 1901. Throughout his life, Scheler entertained a strong interest in the philosophy of American pragmatism (Eucken corresponded with William James).

He taught at Jena from 1900 to 1906. From 1907 to 1910, he taught at the University of Munich, where his study of Edmund Husserl's phenomenology deepened. Scheler had first met Husserl at the Halle in 1902. At Munich, Husserl's own teacher Franz Brentano was still lecturing, and Scheler joined the Phenomenological Circle in Munich, centred around M. Beck, Th. Conrad, J. Daubert, M. Geiger, Dietrich von Hildebrand, Theodor Lipps, and A. Pfaender. Scheler was never a student of Husserl's and overall, their relationship remained strained. Scheler, in later years, was rather critical of the "master's" Logical Investigations (1900/01) and Ideas I (1913), and he also was to harbour reservations about Being and Time by Martin Heidegger. Due to personal matters he was caught up in the conflict between the predominantly Catholic university and the local socialist media, which led to the loss of his Munich teaching position in 1910. From 1910 to 1911, Scheler briefly lectured at the Philosophical Society of Göttingen, where he made and renewed acquaintances with Theodore Conrad, Hedwig Conrad-Martius, Moritz Geiger, Jean Hering, Roman Ingarden, Dietrich von Hildebrand, Husserl, Alexandre Koyre, and Adolf Reinach. Edith Stein was one of his students, impressed by him "way beyond philosophy". Thereafter, he moved to Berlin as an unattached writer and grew close to Walther Rathenau and Werner Sombart.

Scheler has exercised a notable influence on Catholic circles to this day, including his student Stein and Pope John Paul II who wrote his Habilitation and many articles on Scheler's philosophy. Along with other Munich phenomenologists such as Reinach, Pfänder and Geiger, he co-founded in 1912 the famous Jahrbuch für Philosophie und phänomenologische Forschung, with Husserl as main editor.

While his first marriage had ended in divorce, Scheler married Märit Furtwängler in 1912, who was the sister of the noted conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler. During World War I (1914 – 1918), Scheler was initially drafted but later discharged because of astigmia of the eyes. He was passionately devoted to the defence of both war and Germany's cause during the conflict. His conversion to Catholicism dates to this period.

In 1919, he became professor of philosophy and sociology at the University of Cologne. He stayed there until 1928. Early that year, he accepted a new position at the University of Frankfurt. He looked forward to meeting here Ernst Cassirer, Karl Mannheim, Rudolph Otto and Richard Wilhelm, sometimes referred to in his writings. In 1927 at a conference in Darmstadt, near Frankfurt, arranged by Hermann Keyserling, Scheler delivered a lengthy lecture, entitled 'Man's Particular Place' (Die Sonderstellung des Menschen), published later in much abbreviated form as Die Stellung des Menschen im Kosmos [literally:

'Man's Position in the Cosmos']. His well known oratorical style and

delivery captivated his audience for about four hours. Toward

the end of his life, many invitations were extended to him, among them

those from China, India, Japan, Russia, and the United States. However,

on the advice of his physician, he had to cancel reservations already

made with Star Line. At the time, Scheler increasingly focused on political development. He met the Russian emigrant - philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev in

Berlin in 1923. Scheler was the only scholar of rank of the then German

intelligentsia who gave warning in public speeches delivered as early

as 1927 of the dangers of the growing Nazi movement and Marxism.

'Politics and Morals', 'The Idea of Eternal Peace and Pacifism' were

subjects of talks he delivered in Berlin in 1927. His analyses of capitalism revealed it to be a calculating, globally growing 'mind-set', rather than an economic system. While economic capitalism may have had some roots in ascetic Calvinism (cf. Max Weber), its very mind-set, however, is argued by Scheler to have had its origin in modern, subconscious angstas

expressed in increasing needs for financial and other securities, for

protection and personal safeguards as well as for rational

manageability of all entities. However, the subordination of the value

of the individual person to this mind-set was sufficient reason for Max

Scheler to denounce it and to outline and predict a whole new era of

culture and values, which he called 'The World-Era of Adjustment'. Scheler

also advocated an international university to be set up in Switzerland

and was at that time supportive of programs such as 'continuing education' and of what he seems to have been the first to call a 'United States of Europe'.

He deplored the gap existing in Germany between power and mind, a gap

which he regarded as the very source of an impending dictatorship and

the greatest obstacle to the establishment of German democracy. Five

years after his death, the Nazi dictatorship (1933 – 1945) suppressed

Scheler's work. When the editors of Geisteswissenschaften invited Scheler (about 1913/14) to write on the then developing philosophical method of phenomenology, Scheler indicated a reservation concerning the task because he could

only report his own viewpoint on phenomenology and there was no

"phenomenological school" defined by universally accepted theses. There

was only a circle of philosophers bound by a "common bearing and

attitude toward philosophical problems." Scheler never agreed with Husserl that

phenomenology is a method in the strict sense, but rather "an attitude

of spiritual seeing... something which otherwise remains hidden...." Calling

phenomenology a method fails to take seriously the phenomenological

domain of original experience: the givenness of phenomenological facts

(essences or values as a priori) "before they have been fixed by logic," and

prior to assuming a set of criteria or symbols, as is the case in the

empirical and human sciences as well as other (modern) philosophies

which tailor their methods to those of the sciences. Rather, that which is given in phenomenology "is

given only in the seeing and experiencing act itself." The essences are

never given to an 'outside' observer with no direct contact with the

thing itself. Phenomenology is an engagement of phenomena, while

simultaneously a waiting for its self-givenness; it is not a methodical

procedure of observation as if its object is stationary. Thus, the

particular attitude (Geisteshaltung, lit. "disposition of the

spirit" or "spiritual posture") of the philosopher is crucial for the

disclosure, or seeing, of phenomenological facts. This attitude is

fundamentally a moral one, where the strength of philosophical inquiry

rests upon the basis of love. Scheler describes the essence of philosophical thinking as "a

love-determined movement of the inmost personal self of a finite being

toward participation in the essential reality of all possibles." The movement and act of love is important for philosophy for

two reasons: (1) If philosophy, as Scheler describes it, hearkening

back to the Platonic tradition, is a participation in a "primal essence

of all essences" (Urwesen), it follows that for this

participation to be achieved one must incorporate within oneself the

content or essential characteristic of the primal essence. For

Scheler, such a primal essence is most characterized according to love,

thus the way to achieve the most direct and intimate participation is

precisely to share in the movement of love. It is important to mention,

however, that this primal essence is not an objectifiable entity whose

possible correlate is knowledge; thus, even if philosophy is always

concerned with knowing, as Scheler would concur, nevertheless, reason

itself is not the proper participative faculty by which the greatest

level of knowing is achieved. Only when reason and logic have behind

them the movement of love and the proper moral preconditions can one

achieve philosophical knowledge. (2)

Love is likewise important insofar as its essence is the condition for

the possibility of the givenness of value-objects and especially the

givenness of an object in terms of its highest possible value. Love is

the movement which "brings about the continuous emergence of

ever-higher value in the object -- just as if it was streaming out from

the object of its own accord, without any sort of exertion... on the

part of the lover. ...true love open our spiritual eyes to ever-higher

values in the object loved." Hatred,

on the other hand, is the closing off of oneself or closing ones eyes

to the world of values. It is in the latter context that

value-inversions or devaluations become prevalent, and are sometimes

solidified as proper in societies. Furthermore, by calling love a

movement, Scheler hopes to dispel the interpretation that love and hate

are only reactions to felt values rather than the very ground for the

possibility of value-givenness (or value-concealment). Scheler writes,

"Love and hate are acts in which the value-realm accessible to the

feelings of a being... is either extended or narrowed." Love

and hate are to be distinguished from sensible and even psychical

feelings; they are, instead, characterized by an intentional function

(one always loves or hates something)

and therefore must belong to the same anthropological sphere as

theoretical consciousness and the acts of willing and thinking.

Scheler, therefore calls love and hate, "spiritual feelings," and are

the basis for an "emotive a priori"

insofar as values, through love, are given in the same manner as are

essences, through cognition. In short, love is a value-cognition, and

insofar as it is determinative of the way in which a philosopher

approaches the world, it is also indicative of a phenomenological

attitude. A fundamental aspect of Scheler's phenomenology is the extension of the realm of the a priori to include not only formal propositions, but material ones as well. Kant's identification of the a priori with

the formal was a "fundamental error" which is the basis of his ethical

formalism. Furthermore, Kant erroneously identified the realm of the

non-formal (material) with sensible or empirical content. The heart of

Scheler's criticism of Kant is within his theory of values. Values are given a priori,

and are "feelable" phenomena. The intentional feeling of love discloses

values insofar as love opens a person evermore to beings-of-value (Wertsein). Additionally,

values are not formal realities; they do not exist somewhere apart from

the world and their bearers, and they only exist with a value-bearer,

as a value-being. They are, therefore, part of the realm of a material a priori.

Nevertheless, values can vary with respect to their bearers without

there ever occurring an alteration in the object as bearer. E.g., the

value of a specific work of art or specific religious articles may vary

according to differences of culture and religion. However, this

variation of values with respect to their bearers by no means amounts

to the relativity of values as such, but only with respect to the

particular value-bearer. As such, the values of culture are always

spiritual irrespective of the objects that may bear this value, and

values of the holy still remain the highest values regardless of their

bearers. According to Scheler, the disclosure of the value-being of an

object precedes representation. The axiological reality

of values is given prior to knowing, but, upon being felt through

value-feeling, can be known (as to their essential interconnections).

Values and their corresponding disvalues are ranked according to their

essential interconnections as follows: Further essential interconnections apply with respect to a value's (disvalue's) existence or non-existence: And with respect to values of good and evil: Goodness, however, is not simply "attached" to an act of willing, but originates ultimately within the disposition (Gesinnung) or "basic moral tenor" of the acting person. Accordingly: One

may note that most of the older ethical systems (Kantian formalism,

theonomic ethics, nietzscheanism, hedonism, consequentialism, and

platonism, for example) fall into axiological error by emphasizing one

value-rank to the exclusion of the others. A novel aspect of Scheler's

ethics is the importance of the "kairos" or call of the hour. Moral

rules cannot guide the person to make ethical choices in difficult,

existential life-choices. For Scheler, the very capacity to obey rules

is rooted in the basic moral tenor of the person. A disorder "of the heart" occurs whenever a person prefers a value of a lower rank to a higher rank, or a disvalue to a value. The term Wertsein or value-being is used by Scheler in many contexts, but his untimely death prevented him from working out an axiological ontology.

Another unique and controversial element of Scheler's axiology is the

notion of the emotive a priori: values can only be felt, just as color

can only be seen. Reason cannot think values; the mind can only order

categories of value after lived experience has happened. For Scheler,

the person is the locus of value-experience, a timeless act-being that

acts into time. Scheler's appropriation of a value-based metaphysics

renders his phenomenology quite different from the phenomenology of

consciousness (Husserl, Sartre) or the existential analysis of the being-in-the-world of Dasein (Heidegger). Scheler's concept of the "lived body" was appropriated in the early work of Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Max

Scheler extended the phenomenological method to include a reduction of

the scientific method too, thus questioning the idea of Husserl that

phenomenological philosophy should be pursued as a rigorous science.

Natural and scientific attitudes (Einstellung) are both

phenomenologically counterpositive and hence must be sublated in the

advancement of the real phenomenological reduction which, in the eyes of Scheler, has more the shapes of an allround ascesis (Askese) rather than a mere logical procedure of suspending the existential judgments. The Wesenschau,

according to Scheler, is an act of blowing up the Sosein limits of Sein

A into the essential - ontological domain of Sein B, in short, an

ontological participation of Sosenheiten, seeing the things as such (cf. the Buddhist concept of tathata, and the Christian theological quidditas).