<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Giuseppe Peano, 1858

- Painter Emmanuel Radnitzky (Man Ray), 1890

- 36th President of the United States Lyndon Baines Johnson, 1908

PAGE SPONSOR

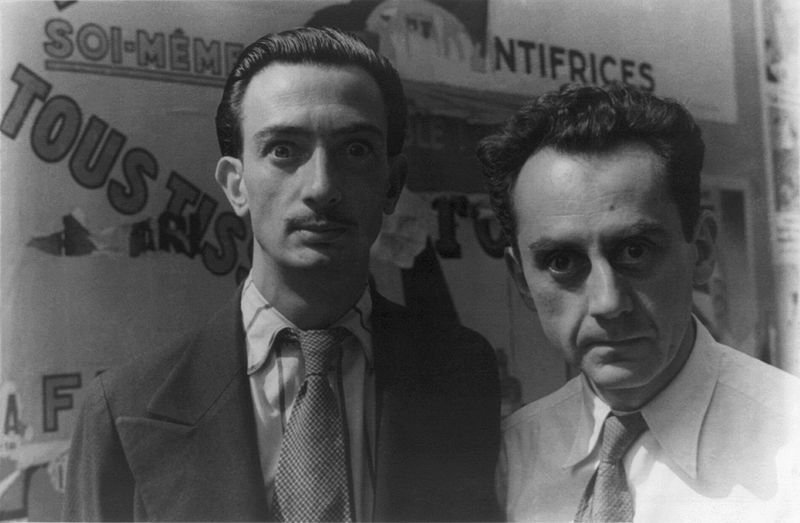

Man Ray (August 27, 1890 – November 18, 1976), born Emmanuel Radnitzky, was an American artist who spent most of his career in Paris, France. Perhaps best described simply as a modernist, he was a significant contributor to both the Dada and Surrealist movements, although his ties to each were informal. Best known in the art world for his avant-garde photography, Man Ray produced major works in a variety of media and considered himself a painter above all. He was also a renowned fashion and portrait photographer. He is noted for his photograms, which he renamed "rayographs" after himself.

While appreciation for Man Ray's work beyond his fashion and portrait photography was slow in coming during his lifetime, especially in his native United States, his reputation has grown steadily in the decades since. In 1999, ARTnews magazine named him one of the 25 most influential artists of the 20th century, citing his groundbreaking photography as well as "his explorations of film, painting, sculpture, collage, assemblage, and prototypes of what would eventually be called performance art and conceptual art" and saying "Man Ray offered artists in all media an example of a creative intelligence that, in its 'pursuit of pleasure and liberty,'" — Man Ray's stated guiding principles — "unlocked every door it came to and walked freely where it would." From the time he began attracting attention as an artist until his death more than sixty years later, Man Ray allowed little of his early life or family background to be known to the public, even refusing to acknowledge that he ever had a name other than Man Ray.

Man Ray was born Emmanuel Radnitzky in South Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, in 1890, the eldest child of recent Russian - Jewish immigrants. The family would eventually include another son and two daughters, the youngest born shortly after they settled in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, New York,

in 1897. In early 1912, the Radnitzky family changed their surname to

Ray, a name selected by Man Ray's brother, in reaction to the ethnic

discrimination and anti-Semitism prevalent

at that time. Emmanuel, who was called "Manny" as a nickname, changed

his first name to Man at this time, and gradually began to use Man Ray

as his combined single name. Man Ray's father was a garment factory worker who also ran a small tailoring business

out of the family home, enlisting his children from an early age. Man

Ray's mother enjoyed making the family's clothes from her own designs

and inventing patchwork items from scraps of fabric. Despite

Man Ray's desire to disassociate himself from his family background,

this experience left an enduring mark on his art. Tailor's dummies,

flat irons, sewing machines, needles, pins, threads, swatches of

fabric, and other items related to clothing and sewing appear at every

stage of his work and in almost every medium. Art historians have also noted similarity in his collage and painting techniques to those used in making clothing. Mason Klein, curator of an exhibition of Man Ray's work at the Jewish Museum entitled “Alias Man Ray: The Art of Reinvention," suggests that Man Ray may have been "the first Jewish avant-garde artist." Man

Ray displayed artistic and mechanical ability from childhood. His

education at Boys' High School from 1904 to 1908 provided him with a

solid grounding in drafting and

other basic art techniques. At the same time, he educated himself with

frequent visits to the local art museums, where he studied the works of

the Old Masters. After graduation from high school, he was offered a scholarship to study architecture but

chose to pursue a career as an artist instead. However much this

decision disappointed his parents' aspirations to upward mobility and

assimilation, they nevertheless rearranged the family's modest living

quarters so that Man Ray could use a room as his studio. He stayed for

the next four years, working steadily toward being a professional

painter, while earning money as a commercial artist and technical illustrator at several Manhattan companies. From

the surviving examples of his work from this period, it appears he

attempted mostly paintings and drawings in 19th century styles. He was

already an avid admirer of avant-garde art of the time, such as the

European modernists he saw at Alfred Stieglitz's "291" gallery and works by the Ashcan School,

but, with a few exceptions, was not yet able to integrate these new

trends into his own work. The art classes he sporadically

attended — including stints at the National Academy of Design and the Art Students League — were of little apparent benefit to him, until he enrolled in the Ferrer School in the autumn of 1912, thus beginning a period of intense and rapid artistic development. Living in New York City, influenced by what he saw at the 1913 Armory Show and in galleries showing contemporary works from Europe, Man Ray's early paintings display facets of cubism. Upon befriending Marcel Duchamp who

was interested in showing movement in static paintings, his works begin

to depict movement of the figures, for example in the repetitive

positions of the skirts of the dancer inThe Rope Dancer Accompanies Herself with Shadows (1916). In 1915, Man Ray had his first solo show of paintings and drawings. His first proto-Dada object, an assemblage titled Self-Portrait, was exhibited the following year. He produced his first significant photographs in 1918. Abandoning conventional painting, Man Ray involved himself with Dada,

a radical anti-art movement, started making objects, and developed

unique mechanical and photographic methods of making images. For the

1918 version of Rope Dancer he combined a spray-gun technique with a pen drawing. Again, like Duchamp, he made "readymades" — objects selected by the artist, sometimes modified and presented as art. His Gift readymade (1921) is a flatiron with metal tacks attached to the bottom, and Enigma of Isidore Ducasse is an unseen object (a sewing machine) wrapped in cloth and tied with cord. Another work from this period, Aerograph (1919), was done with airbrush on glass. In 1920 Ray helped Duchamp make his first machine and one of the earliest examples of kinetic art, the Rotary Glass Plates composed of glass plates turned by a motor. That same year Man Ray, Katherine Dreier and Duchamp founded the Société Anonyme, an itinerant collection which in effect was the first museum of modern art in the U.S. Ray teamed up with Duchamp to publish the one issue of New York Dada in 1920. Man Ray expressed that "dada’s experimentation was no match for the wild and chaotic streets of New York, and he wrote “Dada cannot live in New York. All New York is dada, and will not tolerate a rival.” Man Ray moved to Paris in 1921. Man

Ray met his first wife, the Belgian poet Adon Lacroix, in 1913 in New

York. They married in 1914, separated in 1919, and were formally divorced in 1937.

In July 1921, Man Ray went to live and work in Paris, France, and soon settled in the Montparnasse quarter favored by many artists. Shortly after arriving in Paris, he met and fell in love with Kiki de Montparnasse (Alice Prin),

an artists' model and celebrated character in Paris bohemian circles.

Kiki was Man Ray's companion for most of the 1920s. She became the

subject of some of his most famous photographic images and starred in

his experimental films. In 1929 he began a love affair with the

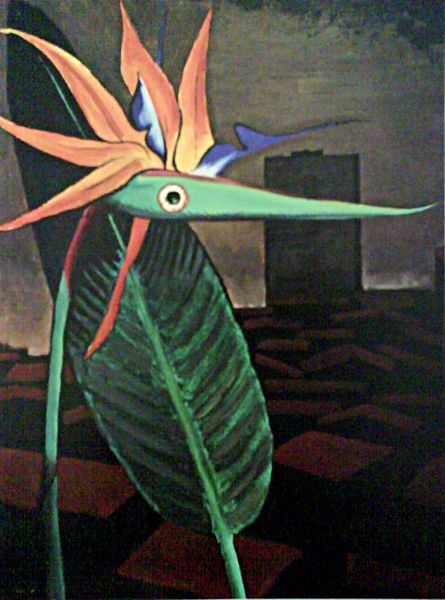

Surrealist photographer Lee Miller. For the next 20 years in Montparnasse, Man Ray made his mark on the art of photography. Significant members of the art world, such as James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, Jean Cocteau, Bridget Bate Tichenor, and Antonin Artaud posed for his camera. With Jean Arp, Max Ernst, André Masson, Joan Miró, and Pablo Picasso, Man Ray was represented in the first Surrealist exhibition at the Galerie Pierre in Paris in 1925. Works from this period include a metronome with an eye, originally titled Object to Be Destroyed. Another important work from this part of Man Ray's life is the Violon d'Ingres, a stunning photograph of Kiki de Montparnasse, styled after the painter/musician, Ingres.

This work is a popular example of how Man Ray could juxtapose disparate

elements in his photography in order to generate meaning. In 1934, surrealist artist Méret Oppenheim,

known for her fur-covered teacup, posed nude for Man Ray in what became

a well-known series of photographs depicting her standing next to a printing press. Together with Lee Miller, who was his photography assistant and lover, Man Ray reinvented the photographic technique of solarization. He also created a technique using photograms he called rayographs, which he described as "pure dadaism". Man Ray directed a number of influential avant-garde short films, known as Cinéma Pur, such as Le Retour à la Raison (2 mins, 1923); Emak-Bakia (16 mins, 1926); L'Étoile de Mer (15 mins, 1928); and Les Mystères du Château de Dé (20 mins, 1929). Man Ray also assisted Marcel Duchamp with his film Anemic Cinema (1926) and Fernand Léger with his film Ballet Mécanique (1924). Man Ray also appeared in René Clair's film Entr'acte (1924), in a brief scene playing chess with Duchamp. Duchamp, Man Ray, and Francis Picabia were friends as well as collaborators, connected by their experimental, entertaining, and innovative art. Later in life, Man Ray returned to the United States, having been forced to leave Paris due to the dislocations of the Second World War. He lived in Los Angeles, California, from 1940 until 1951. A few days after arriving in Los Angeles, Man Ray met Juliet Browner, a first generation American of Rumanian - Jewish lineage; a trained dancer and experienced artists' model. They began living together almost immediately, and married in 1946 in a double wedding with their friends Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning. However, he called Montparnasse home and he returned there. In 1963 he published his autobiography, Self-Portrait, which was republished in 1999. He died in Paris on November 18, 1976 of a lung infection, and was interred in the Cimetière du Montparnasse, Paris. His epitaph reads: unconcerned, but not indifferent. When Juliet Browner died in 1991, she was interred in the same tomb. Her epitaph reads, together again. Juliet set up a trust for his work and made many donations of his work to museums.