<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Giuseppe Peano, 1858

- Painter Emmanuel Radnitzky (Man Ray), 1890

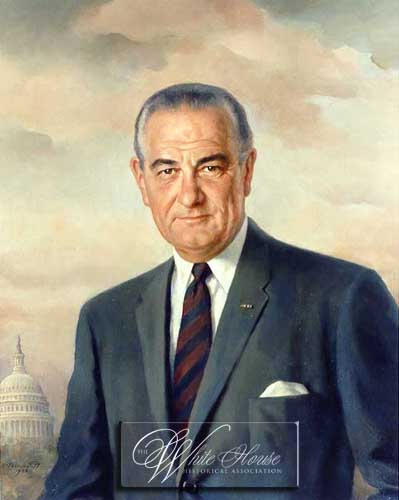

- 36th President of the United States Lyndon Baines Johnson, 1908

PAGE SPONSOR

Lyndon Baines Johnson (August 27, 1908 – January 22, 1973), often referred to as LBJ, served as the 36th President of the United States from 1963 to 1969 after his service as the 37th Vice President of the United States from 1961 to 1963. He is one of four Presidents who served in all four elected Federal offices of the United States: Congressman, Senator, Vice President and President.

Johnson, a Democrat, served as a United States Representative from Texas, from 1937 – 1949 and as United States Senator from 1949 – 1961, including six years as United States Senate Majority Leader, two as Senate Minority Leader and two as Senate Majority Whip. After campaigning unsuccessfully for the Democratic nomination in 1960, Johnson was asked by John F. Kennedy to be his running mate for the 1960 presidential election. Johnson succeeded to the presidency following the assassination of John F. Kennedy, completed Kennedy's term and was elected President in his own right, winning by a large margin in the 1964 Presidential election. Johnson was greatly supported by the Democratic Party and, as President, was responsible for designing the "Great Society" legislation that included laws that upheld civil rights, Public Broadcasting, Medicare, Medicaid, environmental protection, aid to education, and his "War on Poverty."

He was renowned for his domineering personality and the "Johnson

treatment," his coercion of powerful politicians in order to advance

legislation. Simultaneously, he greatly escalated direct American involvement in the Vietnam War. As the war dragged on, Johnson's popularity as President steadily declined. After the 1966 mid-term Congressional elections, his re-election bid in the 1968 United States presidential election collapsed

as a result of turmoil within the Democratic Party related to

opposition to the Vietnam War. He withdrew from the race amid growing

opposition to his policy on the Vietnam War and a worse than expected

showing in the New Hampshire primary.

Despite the failures of his foreign policy, Johnson is ranked favorably

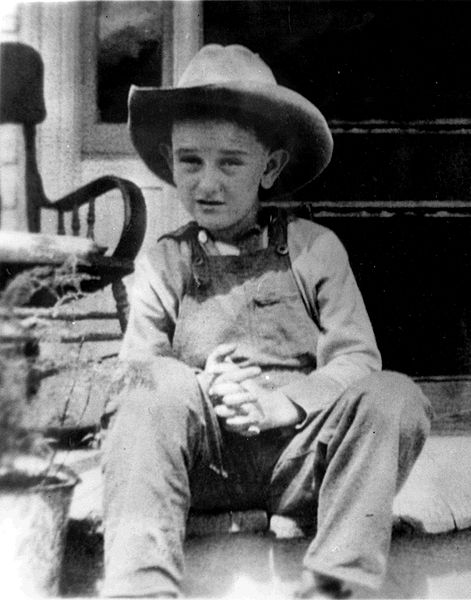

among some historians because of his domestic policies. Lyndon Baines Johnson was born near Stonewall, Texas, on August 27, 1908, in a small farmhouse on the Pedernales River. His parents, Samuel Ealy Johnson, Jr. and Rebekah Baines, had three girls and two boys: Johnson and his brother, Sam Houston Johnson (1914 – 1978), and sisters Rebekah (1910 – 1978), Josefa (1912 – 1961), and Lucia (1916 – 1997). The nearby small town of Johnson City, Texas was named after Johnson's father's cousin, James Polk Johnson, whose forebears had moved west from Georgia. The Johnsons were originally of Scots-Irish and English royal

ancestry. In school, Johnson was an awkward, talkative youth and was

elected president of his 11th-grade class. He graduated from Johnson

City High School in 1924 having participated in public speaking, debate, and baseball. Johnson was maternally descended from a pioneer Baptist clergyman, George Washington Baines, who pastored some eight churches in Texas as well as others in Arkansas and Louisiana. Baines was also the president of Baylor University during the American Civil War. George Baines was the grandfather of Johnson's mother, Rebekah Baines Johnson (1881 – 1958). Johnson's grandfather Samuel Ealy Johnson, Sr. was raised as a Baptist. Subsequently, in his early adulthood, he became a member of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). In his later years he became a Christadelphian. According to Lady Bird Johnson, Johnson's father also joined the Christadelphian Church toward the end of his life. Later, as a politician Johnson was influenced in his attitude towards the Jews by the religious beliefs that his family, especially his grandfather, had shared with him (Operation Texas). In 1926, Johnson enrolled in Southwest Texas State Teachers' College (now Texas State University - San Marcos). He worked his way through school, participated in debate and campus politics, and edited the school newspaper called The College Star, now known as The University Star. He

dropped out of school in 1927 and returned one year later, graduating

in 1930. The college years refined his skills of persuasion and

political organization. In 1927 Johnson taught mostly Mexican children

at the Welhausen School in Cotulla, some ninety miles south of San Antonio in La Salle County. In 1930 he taught in Pearsall High School in Pearsall, Texas, and afterwards took a position as teacher of public speaking at Sam Houston High School in Houston. When he returned to San Marcos in 1965, after having signed the Higher Education Act of 1965, Johnson looked back: Johnson married Claudia Alta Taylor (already nicknamed "Lady Bird") of Karnack, Texas, on November 17, 1934, after having attended Georgetown University Law Center for several months. They had two daughters, Lynda Bird, born in 1944, and Luci Baines,

born in 1947. Johnson enjoyed giving people and animals his own

initials; his daughters' given names are examples, as was his dog,

Little Beagle Johnson. In 1935, he was appointed head of the Texas National Youth Administration,

which enabled him to use the government to create education and job

opportunities for young people. He resigned two years later to run for

Congress. Johnson, a notoriously tough boss throughout his career,

often demanded long workdays and work on weekends. He

was described by friends, fellow politicians, and historians as

motivated throughout his life by an exceptional lust for power and

control. As Johnson's biographer Robert Caro observes, "Johnson's ambition was uncommon — in the degree to which it was

unencumbered by even the slightest excess weight of ideology, of

philosophy, of principles, of beliefs." In 1937 Johnson successfully contested a special election for Texas's 10th congressional district, which covered Austin and the surrounding hill country. He ran on a New Deal platform and was effectively aided by his wife. He served in the House from April 10, 1937, to January 3, 1949. President Franklin D. Roosevelt found

Johnson to be a welcome ally and conduit for information, particularly

with regard to issues concerning internal politics in Texas (Operation Texas) and the machinations of Vice President John Nance Garner and Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn. Johnson was immediately appointed to the Naval Affairs Committee.

He worked for rural electrification and other improvements for his

district. Johnson steered the projects towards contractors that he

personally knew, such as the Brown Brothers, Herman and George, who would finance much of Johnson's future career. In 1941, he ran for the U.S. Senate in a special election against the sitting Governor of Texas, radio personality W. Lee "Pappy" O'Daniel. Johnson lost the election. After America entered World War II in December 1941, Johnson, still in Congress, became a commissioned officer in the Naval Reserve, then asked Undersecretary of the Navy James Forrestal for a combat assignment. Instead he was sent to inspect the shipyard facilities in Texas and on the West Coast. In the spring of 1942, President Roosevelt needed his own reports on what conditions were like in the Southwest Pacific.

Roosevelt felt information that flowed up the military chain of command

needed to be supplemented by a highly trusted political aide. From a

suggestion by Forrestal, President Roosevelt assigned Johnson to a

three-man survey team of the Southwest Pacific. Johnson reported to General Douglas MacArthur in Australia. Johnson and two Army officers went to the 22d Bomb Group base, which was assigned the high risk mission of bombing the Japanese airbase at Lae in New Guinea.

A colonel took Johnson's original seat on one bomber, and it was shot

down with no survivors. Reports vary on what happened to the B-26 Marauder carrying

Johnson. Some accounts say it was also attacked by Japanese fighters

but survived, while others, including other members of the flight crew,

claim it turned back because of generator trouble before reaching the

objective and before encountering enemy aircraft and never came under

fire, which is supported by official flight records. Other airplanes that continued to the target did come

under fire near the target at about the same time that Johnson's plane

was recorded as having landed back at the original airbase. MacArthur awarded Johnson the Silver Star,

the military's third-highest medal, although it is notable that no

other members of the flight crew were awarded medals, and it is unclear

what Johnson could have done in his role purely as an "observer" to

deserve the medal, even if his aircraft had seen combat. Johnson's

biographer, Robert Caro,

stated, "The most you can say about Lyndon Johnson and his Silver Star

is that it is surely one of the most undeserved Silver Stars in

history, because if you accept everything that he said, he was still in

action for no more than 13 minutes and only as an observer. Men who

flew many missions, brave men, never got a Silver Star." Johnson

reported back to Roosevelt, to the Navy leaders, and to Congress that

conditions were deplorable and unacceptable. He argued the South West

Pacific urgently needed a higher priority and a larger share of war

supplies. The warplanes sent there, for example, were "far inferior" to

Japanese planes, and morale was bad. He told Forrestal that the Pacific

Fleet had a "critical" need for 6,800 additional experienced men.

Johnson prepared a twelve-point program to upgrade the effort in the

region, stressing "greater cooperation and coordination within the

various commands and between the different war theaters." Congress

responded by making Johnson chairman of a high powered subcommittee of

the Naval Affairs committee. With a mission similar to that of the Truman Committee in

the Senate, he probed into the peacetime "business as usual"

inefficiencies that permeated the naval war and demanded that admirals

shape up and get the job done. However, Johnson went too far when he

proposed a bill that would crack down on the draft exemptions of

shipyard workers if they were absent from work too often. Organized

labor blocked the bill and denounced Johnson. Still, Johnson's mission

had a substantial impact because it led to upgrading the South Pacific

theater and aided the overall war effort immensely. Johnson's

biographer concludes, "The mission was a temporary exposure to danger

calculated to satisfy Johnson's personal and political wishes, but it

also represented a genuine effort on his part, however misplaced, to improve the lot of America's fighting men." In the 1948 elections, Johnson again ran for the Senate and won. This election was highly controversial: in a three way Democratic Party primary Johnson faced a well known former governor, Coke Stevenson,

and a third candidate. Johnson drew crowds to fairgrounds with his

rented helicopter dubbed "The Johnson City Windmill". He raised money

to flood the state with campaign circulars and won over conservatives

by voting for the Taft-Hartley act (curbing union power) as well as by criticizing unions. Stevenson

came in first but lacked a majority, so a runoff was held. Johnson

campaigned even harder this time around, while Stevenson's efforts were

surprisingly poor. The runoff count took a week. The Democratic State

Central Committee (not the state, because the matter was a party

primary) handled the count, and it finally announced that Johnson had

won by 87 votes. By a majority of one member (29 - 28) the committee

voted to certify Johnson's nomination, with the last vote cast on

Johnson's behalf by Temple, Texas, publisher Frank W. Mayborn, who rushed back to Texas from a business trip in Nashville, Tennessee. There

were many allegations of fraud on both sides. Thus, one writer alleges

that Johnson's campaign manager, future Texas governor John B. Connally, was connected with 202 ballots in Precinct 13 in Jim Wells County that had curiously been cast in alphabetical order and

all just at the close of polling. (All of the people whose names

appeared on the ballots were found to have been dead on election day.) Robert Caro argued

in his 1989 book that Johnson had stolen the election in Jim Wells

County and other counties in South Texas, as well as rigging 10,000

ballots in Bexar County alone. A judge, Luis Salas, said in 1977 that he had certified 202 fraudulent ballots for Johnson. The state Democratic convention upheld Johnson. Stevenson went to court, but — with timely help from his friend Abe Fortas — Johnson prevailed. Johnson was elected senator in November and went to Washington, D.C., tagged with the ironic label "Landslide Lyndon," which he often used deprecatingly to refer to himself. Once

in the Senate, Johnson was known among his colleagues for his highly

successful "courtships" of older senators, especially Senator Richard Russell, patrician leader of the Conservative coalition and

arguably the most powerful man in the Senate. Johnson proceeded to gain

Russell's favor in the same way that he had "courted" Speaker Sam

Rayburn and gained his crucial support in the House. Johnson

was appointed to the Senate Armed Services Committee, and later in 1950

he helped create the Preparedness Investigating Subcommittee. Johnson

became its chairman and conducted investigations of defense costs and

efficiency. These investigations tended to dig out old forgotten

investigations and demand actions that were already being taken by the Truman Administration,

although it can be said that the committee's investigations caused the

changes. However, Johnson's brilliant handling of the press, the

efficiency with which his committee issued new reports, and the fact

that he ensured every report was endorsed unanimously by the committee

all brought him headlines and national attention. Johnson used his

political influence in the Senate to receive broadcast licenses from the Federal Communications Commission in his wife's name. In 1951, Johnson was chosen as Senate Majority Whip under a new Majority Leader, Ernest McFarland of Arizona, and served from 1951 to 1953. In the 1952 general election Republicans won a majority in both House and Senate. Among defeated Democrats that year was McFarland, who lost to then little known Barry Goldwater, Johnson's future presidential opponent. In

January 1953, Johnson was chosen by his fellow Democrats to be the

minority leader. Thus, he became the least senior Senator ever elected

to this position, and one of the least senior party leaders in the

history of the Senate. The whip is usually first in line to replace

party leader (e.g., most recently whip Harry Reid became Senate Minority Leader after Tom Daschle's defeat). One

of his first actions was to eliminate the seniority system in

appointment to a committee, while retaining it in terms of

chairmanships. In the 1954 election,

Johnson was re-elected to the Senate, and since the Democrats won the

majority in the Senate, Johnson became majority leader. Former majority

leader, William Knowland was

elected minority leader. Johnson's duties were to schedule legislation

and help pass measures favored by the Democrats. Johnson, Rayburn and

President Dwight D. Eisenhower worked

smoothly together in passing Eisenhower's domestic and foreign agenda.

As Majority Leader, Johnson was responsible for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first civil rights legislation passed by the Senate since Reconstruction. Historians

Caro and Dallek consider Lyndon Johnson the most effective Senate

majority leader in history. He was unusually proficient at gathering

information. One biographer suggests he was "the greatest intelligence

gatherer Washington has ever known", discovering exactly where every

Senator stood, his philosophy and prejudices, his strengths and

weaknesses, and what it took to break him. Robert Baker claimed that Johnson would occasionally send senators on NATO trips in order to avoid their dissenting votes. Central to Johnson's control was "The Treatment", described by two journalists: Johnson's success in the Senate made him a possible Democratic presidential candidate. He was the "favorite son"

candidate of the Texas delegation at the Party's national convention in

1956. In 1960, after the failure of the "Stop Kennedy" coalition he had

formed with Adlai Stevenson, Stuart Symington, and Hubert Humphrey, Johnson received 409 votes on the only ballot at the Democratic convention, which nominated John F. Kennedy. Tip O'Neill, then a representative from Kennedy's home state of Massachusetts,

recalled that Johnson approached him at the convention and said, "Tip,

I know you have to support Kennedy at the start, but I'd like to have

you with me on the second ballot." O'Neill replied, "Senator, there's

not going to be any second ballot." Kennedy

realized that he could not be elected without support of traditional

Southern Democratic votes, many of whom had backed Johnson. Therefore,

Johnson was offered the vice-presidential nomination. Some sources

(such as Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.'s) state that Kennedy offered the position to Johnson as a courtesy and did not expect him to accept. Others (such as W. Marvin Watson) say that the Kennedy campaign was desperate to win the 1960 election against Richard Nixon and Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., and needed Johnson on the ticket to help carry Southern states. According to still other sources, Kennedy did not want Johnson as his running mate and

did not want to ask him. Kennedy's reported choice was Symington.

Johnson, however, decided to seek the Vice Presidency and with Speaker

Rayburn's help pressured Kennedy to give him a spot. At

the same time as his Vice Presidential run, Johnson also sought a third

term in the U.S. Senate. According to Robert Caro, "On November 5,

1960, Lyndon Johnson won election for both the vice presidency of the

United States, on the Kennedy-Johnson ticket, and for a third term as

Senator (he had Texas law changed to allow him to run for both

offices). When he won the vice presidency, he made arrangements to

resign from the Senate, as he was required to do under federal law, as

soon as it convened on January 3, 1961." (In 1988, Lloyd Bentsen, the Vice Presidential running mate of Democratic presidential candidate Michael Dukakis, and also a Senator from Texas, took advantage of "Lyndon's law," and was able to retain his seat in the Senate despite Dukakis' loss to George H.W. Bush. The same went for Senator Joe Lieberman of Connecticut in 2000 after Al Gore lost to George W. Bush. In 2008, Joseph Biden was

elected Vice President and was re-elected U.S. Senator, as Johnson had

done in 1960.) Johnson was re-elected Senator with 1,306,605 votes

(58%) to Republican John Tower's 927,653 (41.1%). Fellow Democrat William A. Blakley was appointed to replace Johnson as Senator, but Blakley lost a special election in May 1961 to Tower. After

the election, Johnson found himself powerless. He initially attempted

to transfer the authority of Senate Majority Leader to the Vice

Presidency, since that office made him President of the Senate, but

faced vehement opposition from the Democratic Caucus, including members

he'd counted as his supporters. His lack of influence was thrown into relief later that year when Kennedy appointed Johnson's friend Sarah T. Hughes to

a federal judgeship; whereas Johnson had tried and failed to garner the

nomination for Hughes at the beginning of his vice presidency, House Speaker Sam Rayburn wrangled the appointment from Kennedy in exchange for support of an administration bill. Despite

Kennedy's efforts to keep Johnson busy, informed, and at the White

House often, his advisors and even some of his family were more

dismissive to the Texan. Kennedy appointed him to jobs such as head of

the President's Committee on Equal Employment Opportunities, through

which he worked with African Americans and other minorities. Though Kennedy may have intended this to remain a more nominal position, Taylor Branch in Pillar of Fire contends

that Johnson served to push the Kennedy administration's actions for

civil rights further and faster than Kennedy originally intended to go.

Branch notes the irony of Johnson, who the Kennedy family hoped would

appeal to conservative southern voters, being the advocate for civil rights. In particular he notes Johnson's Memorial Day 1963 speech at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, as being a catalyst that led to more action. Johnson

took on numerous minor diplomatic missions, which gave him limited

insights into global issues. He was allowed to observe Cabinet and National Security Council meetings.

Kennedy did give Johnson control over all presidential appointments

involving Texas, and he was appointed chairman of the President's Ad

Hoc Committee for Science. When, in April 1961, the Soviets beat the

U.S. with the first manned spaceflight, Kennedy tasked Johnson with coming up with a 'scientific bonanza' that would prove world leadership. Johnson knew that Project Apollo and an enlarged NASA were feasible, so he steered the recommendation towards a program for landing an American on the Moon. Johnson was touched by a Senate scandal in August 1963 when Bobby Baker, the Senate Majority Secretary and a protege of Johnson's, came under investigation by the Senate Rules Committee for allegations of bribery and

financial malfeasance. One witness alleged that Baker had arranged for

the witness to give kickbacks for the Vice President. Baker resigned in

October, and the White House managed to quash the investigation from

expanding to Johnson. The negative publicity from the affair, however,

fed rumors in Washington circles that Kennedy would drop Johnson from

the presidential ticket in 1964. Johnson was sworn in as President on Air Force One at Love Field Airport in Dallas on November 22, 1963 two hours and eight minutes after President Kennedy was assassinated in Dealey Plaza in Dallas. He was sworn in by Federal Judge Sarah T. Hughes,

a family friend, making him the first President sworn in by a woman. He

is also the only President to have been sworn in on Texas soil. Johnson

did not swear on a Bible, as there were none on Air Force One; a Roman Catholic missal was found in Kennedy's desk and was used for the swearing-in ceremony. In

the days following the assassination, Lyndon B. Johnson made an address

to Congress: "No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor

President Kennedy's memory than the earliest possible passage of the

Civil Rights Bill for which he fought so long." Johnson created a panel headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren, known as the Warren Commission, to investigate Kennedy's assassination. The commission conducted hearings and concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald acted

alone in the assassination. Not everyone agreed with the Warren

Commission, however, and numerous public and private investigations

continued for decades after Johnson left office. The

wave of national grief following the assassination gave enormous

momentum to Johnson's promise to carry out Kennedy's programs. He

retained senior Kennedy appointees, some for the full term of his

presidency. The late President's brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy,

with whom Johnson had a notoriously difficult relationship, remained in

office for a few months until leaving in 1964 to run for the Senate. Robert

F. Kennedy has been quoted as saying that LBJ was "mean, bitter,

vicious -- [an] animal in many ways... I think his reactions on a lot of

things are correct... but I think he’s got this other side of him and

his relationship with human beings which makes it difficult unless you

want to ‘kiss his behind’ all the time. That is what Bob McNamara suggested to me... if I wanted to get along."

On September 7, 1964, Johnson's campaign managers for the 1964 presidential election broadcast the "Daisy ad". It portrayed a little girl picking petals from a daisy,

counting up to ten. Then a baritone voice took over, counted down from

ten to zero and the visual showed the explosion of a nuclear bomb. The

message conveyed was that electing Barry Goldwater president

held the danger of nuclear war. Although it only aired one time, it

became an issue during the campaign. Johnson won the presidency by a

landslide with 61% of the vote and the then widest popular margin in

the 20th century — more than 15 million votes (this was later

surpassed by incumbent President Nixon's defeat of Senator McGovern in 1972). Johnson's popular vote margin of over 22 percentage points is a record that stands to this day. In the summer of 1964, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP)

was organized with the purpose of challenging Mississippi's all-white

and anti-civil rights delegation to the Democratic National Convention

of that year as not representative of all Mississippians. At the national convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, the

MFDP claimed the seats for delegates for Mississippi, not on the

grounds of the Party rules, but because the official Mississippi

delegation had been elected by a primary conducted under Jim Crow laws in

which blacks were excluded because of poll taxes, literacy tests, and

even violence against black voters. The national Party’s liberal

leaders supported a compromise in which the white delegation and the

MFDP would have an even division of the seats; Johnson was concerned

that, while the regular Democrats of Mississippi would probably vote

for Goldwater anyway, if the Democratic Party rejected the regular

Democrats, he would lose the Democratic Party political structure that

he needed to win in the South. Eventually, Hubert Humphrey, Walter Reuther and black civil rights leaders (including Roy Wilkins, Martin Luther King, and Bayard Rustin)

worked out a compromise with MFDP leaders: the MFDP would receive two

non-voting seats on the floor of the Convention; the regular

Mississippi delegation would be required to pledge to support the party

ticket; and no future Democratic convention would accept a delegation

chosen by a discriminatory poll. When the leaders took the proposal

back to the 64 members who had made the bus trip to Atlantic City, they

voted it down. As MFDP Vice Chair Fannie Lou Hamer said,

"We didn't come all the way up here to compromise for no more than we’d

gotten here. We didn't come all this way for no two seats, 'cause all

of us is tired." The failure of the compromise effort allowed the rest

of the Democratic Party to conclude that the MFDP was simply being

unreasonable, and they lost a great deal of their liberal support.

After that, the convention went smoothly for Johnson without a searing battle over civil rights. Despite the landslide victory, Johnson, who carried the South as a whole in the election, lost the Deep South states of Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia and South Carolina, the first time a Democratic candidate had done so since Reconstruction. Johnson

won the presidency by a majority of 61 percent, ready to fulfill his

earlier commitment to “carry forward the plans and programs of John

Fitzgerald Kennedy. Not because of our sorrow or sympathy, but because

they are right.” Johnson played a role in a historic episode during the early 1960s, known as the Chicken War. France and West Germany had placed tariffs on imports of U.S. chicken. Diplomacy failed and

on December 4, 1963, two weeks after taking office, President Johnson

imposed a 25 percent tax (almost 10 times the average U.S. tariff) on potato starch, dextrin, brandy, and light trucks. Officially, the tax targeted items imported from Europe as approximating the value of lost American chicken sales to Europe. In retrospect, audio tapes from the Johnson White House, revealed a quid pro quo unrelated to chicken. In January 1964, President Johnson attempted to convince United Auto Workers's president Walter Reuther not

to initiate a strike just prior the 1964 election and to support the

president's civil rights platform. Reuther in turn wanted Johnson to

respond to Volkswagen's increased shipments to the United States. The Chicken Tax directly curtailed importation of German built Volkswagen Type 2 vans in configurations that qualified them as light trucks — that is, commercial vans and pickups. "In

1964 U.S. imports of "automobile trucks" from West Germany declined to

a value of $5.7 million — about one-third the value imported in the

previous year. Soon after, Volkswagen cargo vans and pickup trucks, the

intended targets, "practically disappeared from the U.S. market." As

of 2009, the Chicken tax on light trucks remains in effect, having

protected U.S. domestic automakers from foreign light truck production. Robert Z. Lawrence, professor of International Trade and Investment at Harvard University, contends the Chicken Tax crippled the U.S. automobile industry, by insulating it from real competition in light trucks for 40 years. In conjunction with the civil rights movement, Johnson overcame southern resistance and convinced Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

which outlawed most forms of racial segregation. John Kennedy

originally proposed the Act and had lined up the necessary votes in the

House to pass his civil rights act by the time of his death in November

1963, but it was Johnson who pushed it through the Senate and signed it

into law on July 2, 1964. Legend has it that, as he put down his pen,

Johnson told an aide, "We have lost the South for a generation",

anticipating a coming backlash from Southern whites against Johnson's

Democratic Party. In 1965, he achieved passage of a second civil rights bill, the Voting Rights Act,

which outlawed discrimination in voting, thus allowing millions of

southern blacks to vote for the first time. In accordance with the act,

several states, "seven of the eleven southern states of the former

confederacy" - Alabama, South Carolina, North Carolina, Georgia,

Louisiana, Mississippi, Virginia — were subjected to the procedure

of preclearance in 1965, while Texas, home to the majority of the

African American population at the time, followed in 1975. After the murder of civil rights worker Viola Liuzzo, Johnson went on television to announce the arrest of four Ku Klux Klansmen implicated in her death. He angrily denounced the Klan as a "hooded society of

bigots," and warned them to "return to a decent society before it's too

late." Johnson was the first President to arrest and prosecute members

of the Klan since Ulysses S. Grant about 93 years earlier. He turned the themes of Christian redemption to push for civil rights, thereby mobilizing support from churches North and South. At the Howard University commencement address on June 4, 1965, he said that both the government and the nation needed to help achieve goals: In 1967, Johnson nominated civil rights attorney Thurgood Marshall to be the first African American Associate Justice of the Supreme Court.

Johnson signed the Immigration Act of 1965, which substantially changed U.S. immigration policy toward non-Europeans. While

European born immigrants accounted for nearly 60% of the total

foreign-born population in 1970, they accounted for only 15% in 2000. Immigration doubled between 1965 and 1970, and doubled again between 1970 and 1990. Since the liberalization of immigration policy in 1965, the number of first-generation immigrants living in the United States has quadrupled, from 9.6 million in 1970 to about 38 million in 2007.

In 1964, upon Johnson's request, Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1964 and the Economic Opportunity Act, which was in association with the war on poverty. Johnson set in motion bills and acts, creating programs such as Head Start, food stamps, Work Study, Medicare and Medicaid, which still exist today. The medicare program was established on July 30, 1965, to offer cheaper medical services to the elderly, today covering tens of millions of Americans. Johnson gave the first two Medicare cards to former President Harry S. Truman and his wife Bess after signing the medicare bill at the Truman Library. Lower income groups receive government sponsored medical coverage through the Medicaid program.

On October 22, 1968, Lyndon Johnson signed the Gun Control Act of 1968,

one of the largest and most far reaching federal gun control laws in

American history. This act represented a dramatic increase in federal

power. Much of the motivation for this large expansion of federal gun

regulations came as a response to the murders of John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, and Martin Luther King.

During Johnson's administration, the first human spaceflight to the Moon, Apollo 8, was successfully flown by NASA in

December 1968. The President congratulated the astronauts, saying,

"You've taken ... all of us, all over the world, into a new era."

Major riots in black neighborhoods caused a series of "long hot summers." They started with a violent disturbance in Harlem in 1964 and the Watts district of

Los Angeles in 1965, and extended to 1970. The biggest wave came in

April 1968, when riots occurred in over a hundred cities in the wake of

the assassination of Martin Luther King. Newark burned in 1967, where six days of rioting left 26 dead, 1500 injured, and the inner city a burned out shell. In Detroit in 1967, Governor George Romney sent

in 7400 national guard troops to quell fire bombings, looting, and

attacks on businesses and on police. Johnson finally sent in federal

troops with tanks and machine guns. Detroit continued to burn for three

more days until finally 43 were dead, 2250 were injured, 4000 were

arrested; property damage ranged into the hundreds of millions; much of

inner Detroit was never rebuilt. Johnson called for even more billions

to be spent in the cities and another federal civil rights law

regarding housing, but his political capital had been spent, and his

Great Society programs lost support. Johnson's popularity plummeted as

a massive white political backlash took shape, reinforcing the sense

Johnson had lost control of the streets of major cities as well as his

party. Johnson created the Kerner Commission to study the problem of urban riots, headed by Illinois Governor Otto Kerner. Johnson's problems began to mount in 1966. The press had sensed a "Credibility gap"

between what Johnson was saying in press conferences and what was

happening on the ground in Vietnam, which led to much less favorable

coverage of Johnson. By year's end, the Democratic governor of Missouri warned

that Johnson would lose the state by 100,000 votes, despite a

half-million margin in 1964. "Frustration over Vietnam; too much

federal spending and... taxation; no great public support for your

Great Society programs; and ... public disenchantment with the civil

rights programs" had eroded the President's standing, the governor

reported. There were bright spots, however. In January 1967, Johnson

boasted that wages were the highest in history, unemployment was at a

13-year low, and corporate profits and farm incomes were greater than

ever; however, a 4.5% jump in consumer prices was worrisome, as well as the rise in interest rates. Johnson asked for a temporary 6% surcharge in income taxes to

cover the mounting deficit caused by increased spending. Johnson's

approval ratings stayed below 50%; by January 1967, the number of his

strong supporters had plunged to 16%, from 25% four months before. He

ran about even with Republican George Romney in

trial matchups that spring. Asked to explain why he was unpopular,

Johnson responded, "I am a dominating personality, and when I get

things done I don't always please all the people." Johnson also blamed

the press, saying they showed "complete irresponsibility and lie and

misstate facts and have no one to be answerable to." He also blamed

"the preachers, liberals and professors" who had turned against him. In the congressional elections of 1966, the Republicans gained three seats in the Senate and 47 in the House, reinvigorating the Conservative coalition and making it impossible for Johnson to pass any additional Great Society legislation.

Johnson increasingly focused on the American military effort in Vietnam. He firmly believed in the Domino Theory and that his containment policy required America to make a serious effort to stop all Communist expansion. At

Kennedy's death, there were 16,000 American military advisors in

Vietnam. As President, Lyndon Johnson immediately reversed his

predecessor's order to withdraw 1,000 military personnel by the end of

1963 with his own NSAM #273 on November 26, 1963. Johnson expanded the

numbers and roles of the American military following the Gulf of Tonkin Incident (less than three weeks after the Republican Convention of 1964, which had nominated Barry Goldwater for President). The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution,

which gave the President the exclusive right to use military force

without consulting the Senate, was based on a false pretext, as Johnson

later admitted. It

was Johnson who began America's direct involvement in the ground war in

Vietnam. By 1968, over 550,000 American soldiers were inside Vietnam;

in 1967 and 1968 they were being killed at the rate of over 1,000 a

month. Politically,

Johnson closely watched the public opinion polls. His goal was not to

adjust his policies to follow opinion, but rather to adjust opinion to

support his policies. Until the Tet Offensive of

1968, he systematically downplayed the war: few speeches, no rallies or

parades or advertising campaigns. He feared that publicity would charge

up the hawks who wanted victory, and weaken both his containment policy

and his higher priorities in domestic issues. Jacobs and Shapiro

conclude, "Although Johnson held a core of support for his position,

the president was unable to move Americans who held hawkish and dovish

positions." Polls showed that beginning in 1965, the public was

consistently 40-50% hawkish and 10-25% dovish. Johnson's aides told

him, "Both hawks and doves [are frustrated with the war] ... and take

it out on you.". The

war became very unpopular towards the end of his presidency and a

protest chant was devised, due to the young age of troops being

deployed in the war, which went: 'Hey hey LBJ, how many kids have you

killed today?'. Additionally,

domestic issues were driving his polls down steadily from spring 1966

onward. A few analysts have theorized that "Vietnam had no independent

impact on President Johnson's popularity at all after other effects,

including a general overall downward trend in popularity, had been

taken into account." The

war did, however, grow less popular and continued to split the

Democratic Party. The Republican Party was not completely pro or

anti-war, and Nixon managed to get support from both groups by running

on a reduction in troop levels with an eye toward eventually ending the

campaign. He often privately cursed the Vietnam War, and in a conversation with Robert McNamara, Johnson assailed "the bunch of commies" running the New York Times for their articles against the war effort. Johnson

believed that America could not afford to lose and risk appearing weak

in the eyes of the world. In a discussion about the war with former

President Dwight Eisenhower,

Johnson said he was "trying to win it just as fast as I can in every

way that I know how" and later stated that he needed "all the help I

can get." Johnson escalated the war effort continuously from 1964 to 1968, and the number

of American deaths rose. In two weeks in May 1968 alone American deaths

numbered 1,800 with total casualties at 18,000. Alluding to the Domino Theory, he said, "If we allow Vietnam to fall, tomorrow we’ll be fighting in Hawaii, and next week in San Francisco." After the Tet offensive of January 1968, his presidency was dominated by the Vietnam War more than ever. Following evening news broadcaster Walter Cronkite's

editorial report during the Tet Offensive that the war was unwinnable,

Johnson is reported to have said, "If I've lost Cronkite, I've lost

Middle America." As

casualties mounted and success seemed further away than ever, Johnson's

popularity plummeted. College students and others protested, burned draft cards, and chanted, "Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?" Johnson could scarcely travel anywhere without facing protests, and was not allowed by the Secret Service to attend the 1968 Democratic National Convention, where hundreds of thousands of hippies, yippies, Black Panthers and

other opponents of Johnson's policies both in Vietnam and in the

ghettoes converged to protest. Thus by 1968, the public was polarized,

with the "hawks" rejecting Johnson's refusal to continue the war

indefinitely, and the "doves" rejecting his current war policies.

Support for Johnson's middle position continued to shrink until he

finally rejected containment and sought a peace settlement. By late

summer, however, he realized that Nixon was closer to his position than

Humphrey. However, he continued to support Humphrey publicly in the

election, and personally despised Nixon. One of Johnson's well known

quotes was "the Democratic party at its worst, is still better than the

Republican party at its best". Perhaps Johnson, himself, best summed up his involvement in the Vietnam War as President: In a 1993 interview for the Johnson Presidential Library oral history archives, Johnson's Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara stated that a carrier battle group, the U.S. 6th Fleet, sent on a training exercise toward Gibraltar was re-positioned back towards the eastern Mediterranean to be able to defend Israel during the Six Day War of

June 1967. Given the rapid Israeli advances following their preemptive

strike on Egypt, the administration "thought the situation was so tense

in Israel that perhaps the Syrians, fearing Israel would attack them,

or the Russians supporting the Syrians might wish to redress the

balance of power and might attack Israel". The Soviets learned of this

course correction and regarded it as an offensive move. In a hotline

message from Moscow, Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin said,

"If you want war you're going to get war." McNamara noted, "The reason

this happened was a) the Israelis had knocked hell out of the

Egyptians; b) the Egyptians and Jordanians believed a false charge

that we were bombing Cairo from a carrier, and when Hussein came in the

Israelis knocked hell out of him." The Soviet Union supported its Arab allies. In

May 1967, the Soviets started a surge deployment of their naval forces

into the East Mediterranean. Early in the crisis they began to shadow

the US and British carriers with destroyers and intelligence collecting

vessels. The Soviet naval squadron in the Mediterranean was

sufficiently strong to act as a major restraint on the U.S. Navy. In a 1983 interview with the Boston Globe,

McNamara claimed that "We damn near had war". He said Kosygin was angry

that "we had turned around a carrier in the Mediterranean". Johnson was not disqualified from running for a second full term under the provisions of the 22nd Amendment;

he had served less than 24 months of President Kennedy's term. Had he

stayed in the race and won and served out the new term, he would have

been president for 9 years and 2 months, second only to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Coincidentally, Johnson died just two days after what would have been the end of his second full term. During

1973 testimony before Congress, the CEO of America's largest

cooperative of milk producers said that while Johnson was President,

his cooperative had leased Johnson's private jet at a "plush" price,

which Johnson wanted to continue once he was out of office. Johnson continued the FBI's wiretapping of Martin Luther King, Jr. that had been previously authorized by the Kennedy administration under Attorney General Robert Kennedy. As

a result of listening to the FBI's tapes, remarks on King's personal

lifestyle were made by several prominent officials, including Johnson,

who once said that King was a “hypocritical preacher.” Johnson also authorized the tapping of phone conversations of others, including the Vietnamese friends of a Nixon associate. In Latin America, Johnson directly and indirectly supported the overthrow of left-wing, democratically elected president Juan Bosch of the Dominican Republic and João Goulart of Brazil,

maintaining US support for anti-communist, authoritarian Latin American

regimes. American foreign policy towards Latin America remained largely

static until election of Jimmy Carter to the presidency in 1977. Johnson was often seen as a wildly ambitious, tireless, and imposing figure who

was ruthlessly effective at getting legislation passed. He worked 18-20

hour days without break and was apparently absent any leisure

activities. "There was no more powerful majority leader in American

history," his biographer Robert Dallek writes. Dallek writes that

Johnson had biographies on all the Senators, knew what their ambitions,

hopes, and tastes were and used it to his advantage in securing vote.

Another Johnson biography writes, "He could get up every day and learn

what their fears, their desires, their wishes, their wants were and he

could then manipulate, dominate, persuade and cajole them." At 6ft 4in

tall, Johnson had his own particular brand of persuasion, known as "The

Johnson Treatment". A

contemporary writes, "It was an incredible blend of badgering,

cajolery, reminders of past favours, promises of future favours,

predictions of gloom if something doesn't happen. When that man started

to work on you, all of a sudden, you just felt that you were standing

under a waterfall and the stuff was pouring on you." Johnson

also took on the image of the Texas cattle rancher, after buying a

ranch in Texas and having himself photographed in cowboy attire. After leaving the presidency in 1969, Johnson went home to his ranch in Johnson City, Texas. In 1971, he published his memoirs, The Vantage Point. That year, the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum opened near the campus of The University of Texas at Austin. He donated his Texas ranch in his will to the public to form the Lyndon B. Johnson National Historical Park, with the provision that the ranch "remain a working ranch and not become a sterile relic of the past". During the 1972 presidential election, Johnson supported Democratic presidential nominee George S. McGovern, a Senator from South Dakota, although McGovern had long opposed Johnson's foreign and defense policies. Johnson's protege John Connally had served as President Nixon's Secretary of the Treasury and then stepped down to head "Democrats for Nixon",

a group funded by Republicans. It was the first time that Connally and

Johnson were on opposite sides of a general election campaign. Lyndon Baines Johnson died at his ranch at 3:39 p.m CST (4:39 p.m. EST) on January 22, 1973 at age 64, from a third heart attack. His death came the day before a ceasefire was signed in Vietnam and almost a month after another former president Harry S. Truman died. His health had been affected by years of heavy smoking, poor dietary habits and stress; the former president had severe heart disease.

He had his first, nearly fatal, heart attack in July 1955 and suffered

a second one in April 1972, but had been unable to quit smoking after

he left the oval office in 1969. He was found dead by Secret Service

agents, in his bed, with a telephone in his hand. Shortly

after Johnson's death, his press secretary Tom Johnson telephoned

Walter Cronkite at CBS; Cronkite was live on the air with the CBS Evening News at

the time, and a report on Vietnam was cut abruptly while Cronkite was

still on the line with Johnson so he could break the news. Johnson was honored with a state funeral in which Texas Congressman J.J. Pickle and former Secretary of State Dean Rusk eulogized him at the Capitol. The final services took place on January 25. The funeral was held at the National City Christian Church in Washington, D.C., where he had often worshiped as president. The

service was presided over by President Richard Nixon and attended by

foreign dignitaries such as former Japanese prime minister Eisaku Satō,

who served as Japanese prime minister during Johnson's presidency.

Eulogies were given by the Rev. Dr. George Davis, the church's pastor,

and W. Marvin Watson,

former postmaster general. Nixon did not speak, though he attended, as

is customary for presidents during state funerals, but the eulogists

turned to him and lauded him for his tributes, as Rusk did the day

before. Johnson

was buried in his family cemetery (which can be viewed today by

visitors to the Lyndon B. Johnson National Park in Stonewall, Texas), a

few yards from the house in which he was born. Eulogies were given by John Connally and the Rev. Billy Graham, the minister who officiated the burial rites. The state funeral, the last until Ronald Reagan's in 2004, was part of an unexpectedly busy week in Washington, as the Military District of Washington (MDW) dealt with their second major task in less than a week, beginning with Nixon's second inauguration. Because

of the construction work on the center steps of the East Front,

Johnson's casket traveled the entire length of the Capitol, entering

through the Senate wing steps when taken into the rotunda and exiting through the House wing steps. Also, the MDW and the Armed Forces Inaugural Committee canceled

the remainder of the ceremonies surrounding the inauguration to allow

for a full state funeral, as Johnson died only two days after the

inauguration. The Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas, was renamed the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, and Texas created a legal state holiday to be observed on August 27 to mark Johnson's birthday. It is known as Lyndon Baines Johnson Day. The Lyndon Baines Johnson Memorial Grove on the Potomac was dedicated on September 27, 1974. The Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs was named in his honor, as is the Lyndon B. Johnson National Grassland. Interstate 635 in Dallas is named the Lyndon B. Johnson Freeway. Johnson was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously in 1980. On March 23, 2007, President George W. Bush signed legislation naming the United States Department of Education headquarters after President Johnson. Runway 17R/35L at Austin-Bergstrom International Airport is known as the Lyndon B. Johnson Runway. 2008

was the celebration of the Johnson Centennial featuring special

programs, events, and parties across Texas and in Washington, D.C. Johnson would have been 100 years old on August 27, 2008. The student center at Texas State University is named after the former president.

“ To

shatter forever not only the barriers of law and public practice, but

the walls which bound the condition of many by the color of his skin.

To dissolve, as best we can, the antique enmities of the heart which

diminish the holder, divide the great democracy, and do wrong —

great wrong — to the children of God... ”

The Great Society program,

with its name coined from one of Johnson's speeches, became Johnson's

agenda for Congress in January 1965: aid to education, attack on

disease, Medicare, Medicaid, urban renewal,

beautification, conservation, development of depressed regions, a

wide-scale fight against poverty, control and prevention of crime, and

removal of obstacles to the right to vote. Congress, at times augmenting or amending, enacted many of Johnson's recommendations. Johnson had a lifelong commitment to the belief that education was the cure for both ignorance and poverty, and was an essential component of the American Dream, especially for minorities who endured poor facilities and tight-fisted budgets from local taxes. He

made education a top priority of the Great Society, with an emphasis on

helping poor children. After the 1964 landslide brought in many new

liberal Congressmen, he had the votes for the Elementary and Secondary Education Act

(ESEA)

of 1965. For the first time, large amounts of federal money went to

public schools. In practice ESEA meant helping all public school

districts, with

more money going to districts that had large proportions of students

from poor families (which included all the big cities). However, for

the first time private schools (most of them Catholic schools in the

inner cities) received services, such as library funding, comprising

about 12% of the ESEA budget. As Dallek reports, researchers soon found

that poverty had more to do with family background and neighborhood

conditions than the quantity of education a child received. Early

studies suggested initial improvements for poor kids helped by ESEA

reading and math programs, but later assessments indicated that

benefits faded quickly and left students little better off than those

not in the programs. Johnson’s second major education program was the Higher Education Act of 1965, which focused on funding for lower income students, including grants, work-study money, and government loans. He set up the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts, to support humanists and artists (as the WPA once

did). Although ESEA solidified Johnson's support among K-12 teachers'

unions, neither the Higher Education Act nor the Endowments mollified

the college professors and students growing increasingly uneasy with

the war in Vietnam. In 1967 Johnson signed the Public Broadcasting Act to create educational television programs to supplement the broadcast networks.

“ I knew from the start that I was bound to be crucified either way I moved. If I left the woman I really loved — the Great Society -

in order to get involved in that bitch of a war on the other side of

the world, then I would lose everything at home. All my programs....

But if I left that war and let the Communists take over South Vietnam,

then I would be seen as a coward and my nation would be seen as an

appeaser and we would both find it impossible to accomplish anything

for anybody anywhere on the entire globe. ”

During his presidency, Johnson issued 1187 pardons and commutations, granting over 20% of such requests.

Entering

the 1968 election campaign, initially, no prominent Democratic

candidate was prepared to run against a sitting president of the Democratic party. Only Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota challenged Johnson as an anti-war candidate in the New Hampshire primary,

hoping to pressure the Democrats to oppose the war. On March 12,

McCarthy won 42% of the primary vote to Johnson's 49%, an amazingly

strong showing for such a challenger. Four days later, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy of New York entered the race. Internal polling by Johnson's campaign in Wisconsin,

the next state to hold a primary election, showed the President

trailing badly. Johnson did not leave the White House to campaign. Johnson

had lost control of the Democratic Party, which was splitting into four

factions, each of which despised the other three. The first consisted

of Johnson (and Humphrey), labor unions, and local party bosses (led by Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley).

The second group consisted of students and intellectuals who were

vociferously against the war and rallied behind McCarthy. The third

group were Catholics, Hispanics and African Americans, who rallied behind Robert Kennedy. The fourth group were traditionally segregationist white Southerners, who rallied behind George C. Wallace and the American Independent Party. Vietnam was one of many issues that splintered the party, and Johnson could see no way to win Vietnam and no way to unite the party long enough for him to win re-election. In addition, Johnson was concerned that he might not make it through another term. Therefore,

at the end of a March 31 speech, he shocked the nation when he

announced he would not run for re-election: "I shall not seek, nor will

I accept the nomination of my party for another term as your President." He did rally the party bosses and unions to give Humphrey the nomination at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

However, Johnson had grown to dislike Humphrey by this time; personal

correspondences between the President and some in the Republican Party

suggested Johnson tacitly supported Nelson Rockefeller's campaign.

He reportedly said that if Rockefeller became the Republican nominee,

he would not campaign against him (and would not campaign for Humphrey). In what was termed the October surprise,

Johnson announced to the nation on October 31, 1968, that he had

ordered a complete cessation of "all air, naval and artillery

bombardment of North Vietnam", effective November 1, should the Hanoi Government be willing to negotiate and citing progress with the Paris peace talks. In the end, the divided Democratic Party crumbled enabling Republican Richard Nixon to win the election.