<Back to Index>

- Physician Muhammad ibn Zakariyā al-Rāzī, 865

- Painter Kanō Motonobu, 1476

- Emperor of China Taichang, 1582

PAGE SPONSOR

Kanō Motonobu (August 28, 1476 – November 5, 1559) was a Japanese painter. He was a member of the Kanō school of painting.

Kano Motonobu's father was Kanō Masanobu, the founder of the Kanō school.

The Kano family are presumed to be the descendants from a line of warriors. The warriors are from the Kano district. The Kano district is now called Shizuoka Prefecture. The forebear of this family is Kanō Kagenobu. He seems to have been a retainer of the Imagawa family. It has been reported that he has painted a picture of Mt Fuji. This painting was for a visit to the shogun Ashikaga Yoshinori (1394 – 1441) in 1432. The Kano family is a family that dominated the painting world from the end of the Muromachi period (1333 – 1568) to the end of the Edo period (1600 – 1868). The Kano family is one of the most important lineages in Japanese history.

Kano

Masanobu, Motonobu’s father, was the founder of the Kano tradition.

Kano Masanobu is Kagenobu's son. Kano Masanobu was the official court

painter to the Ashikaga Shogunate in 1481. Masanobu was a professional

artist whose style is derived from Kanga style. Masanobu’s descendants

were the people that made up the Kano School. The Kano School had

secular ink painters. Motonobu was likely trained in Kanga

(Chinese style ink painting) by his father. Motonobu also probably

acquired his skill as a portrait painter from his Masanobu. One example

of this would be the Priest Tōrin, 1521; Kyoto, Ryūanji. Kano Motonobu

formed a formal workshop in the sixteenth century based on Kano

tradition. The Kano tradition is now known as the Kano School. This

family of artists was supported by becoming fanmakers (ogiza). The

family gained financial support from Eimyoin, a subtemple of Tofukuji

in southwest Kyoto. Motonobu was given many commissions for paintings

from a variety of sources. His sources included: the Ashikaga

government, members of the aristocracy, and major Kyoto shrines and

temples. From these commissions Motonobu was able to develop his

painting skills further.

Motonobu, like his father, did commissions for the Ashikaga shoguns. The Ashikaga was a family of military rulers who governed Japan from 1338 to 1573. When Motonobu was only nine he begun to serve the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1436 - 90). Motonobu then paintined for Yoshimasa’s successors. The successors’ names are as follows: Ashikaga Yoshitane (1465 – 1522), Yoshizumi (1478 – 1511) and Yoshiharu (1511 – 50). One member of the elite was Hosokawa Takakuni (1484 – 1531) commissioned Motonobu to paint a set of narrative handscrolls. The handscrolls were commissioned in 1513 and are entitled Kuramadera engi (‘Origins of Kurama temple’; untraced). His clients were from the imperial courts and merchant classes in mainly Kyoto and Sakai. One of Motonobu’s earliest documented contracts was for a set of votive plaques (ema). These plaques depicted the Thirty-six Immortal Poets. It was ordered by a group of Sakai merchants in 1515 for the Shinto shrine of Itsukushima in what is now Hiroshima Prefecture. The Sanjōnishi family liked Motonobu’s work and in 1536 they invited Motonobu to give a painting performance. This family was well associated with the imperial court. The performance was done on a two-panel folding screen and performed in front of a group of guests. Motonobu presented folding screens to Emperor GoNara (reigned 1526 – 57). Motonobu had to be flexible to serve each of the patron’s individualistic taste. Motonobu is considered as the patriarch of the Kano School. Motonobu played an important role because he combined his artistic talent with versatility.

The Kano School is not actually a school, as the title implies, but it is an artistic workshop. The Kano School was organized in a systematic way based on four general characteristics. First, family ties played an integral role. The family tradition has to be pasted down. Records of the family were shown through handbooks, craft techniques, and trade secrets. Secondly, the tradition was passed through to a male member of the family. This statement can seem contradictory because the male member could be an adopted outsider. This ensures that the family could have great talent in their guild. The third characteristic is that there has to be a vertical relationship in the guild; an example would be father to son. The oldest member has to be the head. This rule carries out the Kano tradition from generation to generation. The fourth characteristic is that bonds and alliances are made through contract or marriage. Sometimes when the guild has an enormous project it is better to collaborate. A contract or marriage makes sure that the family has the adequate means for the project. Tosa Mitsunobu, the founder of the Tosa school of painting was Motonobu’s father-in-law. The Tosa School specialized in the Yamato-e (a Japanese painting style). Mitsunobu combing the strong brushwork of suiboku-ga with the decorative appeal of the Yamato-e. This style was suitable for large compositions and it dominated Japanese painting for the next three hundred years.

Motonobu was head of the small Kano workshop in the 1530s. The workshop was located in northern Kyoto. The Kano School only had about ten painters. The workshop consisted of Motonobu’s three sons, Shoei (1519 – 1592), Yusetsu (1514 – 1562), and Joshin. Also in the workshop was Motonobu’s younger brother Yukinobu (1513 – 1575) and some assistants that might have not been blood related. Since Motonobu was the head or chief architect of these paintings he took on the contracting for the projects. He also was responsible for the production and organization of the projects. Motonobu was very involved with the marketing of his work, and also in his studio. He received a broad amount of patronage. He was a very smart businessman. He had a petition presented to a shogun. The petition also included the merchant Hasuike Hideaki (fl. 1539 – 50). The petition applied for a vast amount of production and sales in fans. Motonobu also took on the most salient, detailed parts of the paintings. He devised the compositions in sketches. In large commissions he did the most important rooms in a building. Motonobu's son and assistants would then do the other parts of production. They would grind pigments, prepare the paper, paint the background color or simply fill in large areas of color. As the commissions grew so did the amount of assistants. The assistants, as mentioned before, might have not been hereditary. The hereditary members had the most control over the important parts of the product. The workshop dependent upon the "family". Motonobu provided the organizational and artistic skills necessary. The other parts of the guild are also important because they helped produce the finished product. The reputation of the leader or organizer was very crucial to the workshop. Motonobu had a good reputation and he became very famous in Kyoto, as did his workshop. He was held in very high regard by his generation and some of the commissions he was involved in were very prestigious. Motonobu was involved in the decoration of Ishiyama Honganji in Osaka between 1539 and 1553. Ishiyama Honganji is the chief temple of the Jōdō Shinshū (Pure Land) sect of Buddhism. This is unusual because Motonobu was a member of the Nichiren or Hokke sect. This group was arch-enemies of the Jōdō Shinshū. In 1541, Motonobu sent one hundred fans and three folding screens to the Ming emperor as gifts. Like his father, Motonobu received a series of honorary court and religious titles, culminating in that of hōgen (Eye of the Law), which he was using by 1546.

Motonobu

trained his workshop which was full of members of his family and other

apprentices to execute his many designs. His designs were items like

folding fans to the prominent screen-and-wall paintings of the time.

The workshop trained other artists by having them watch the master

painter work.

The students would watch Motonobu work and would gain experience by

helping with commissions. Motonobu gave students the tools necessary

for them to succeed. He unified the production of the hereditary

members with the other associates in the workshop. He did this by

standardizing his compositions, allowing only minor stylistic changes

in

them. Motonobu also had a style of brushwork that he is very famous

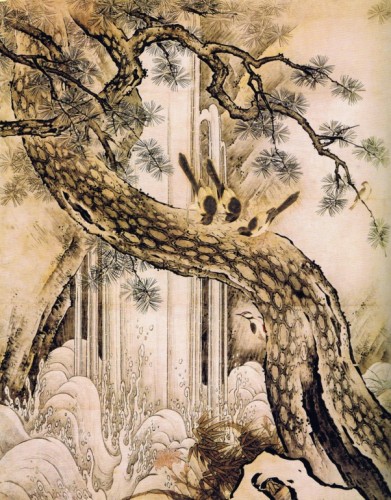

for. Motonobu's paintings have minimal color in them. The forms are

organic, natural, and full of drama. These paintings are also known as

suibokuga (sumi-e) monochromatic water-ink paintings. The brushwork is

very dramatic and expressive. This brushwork became then famous in

subsequent

generations. What works for one generation works for the next. The

students would practice Motonobu’s style daily. Motonobu definitely

lived up to the standards of his patrons. Motonobu was good at

producing landscapes. Motonobu introduced heavily stressed outlines and

bold

decorative patterns. These landscapes were produced in both monochrome

and in lighter colors. Motonobu was very skillful in and he created a

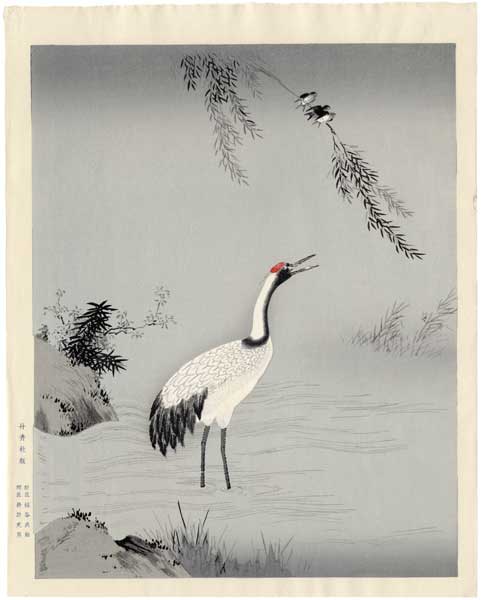

variety of forms. He created figures, and also had flowers and bird

pictures. The screen paintings that Motonobu made served as

architectural decorations. They appealed greatly to the warrior class.

A lot of his paintings are still preserved in temples at Kyoto. His

paintings are on the panels of Reiun-in monastery in Kyoto.

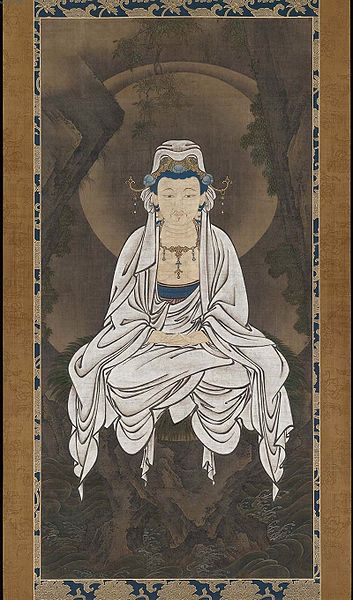

Motonobu did the principle rooms in the monastery. The rooms are decorated with landscape paintings in three different styles. The styles are by three different masters. The soft ink-wash style was made by Mu-ch'i Fa-ch'ang (late 12th – early 13th century). The more rigid, hard, stiff style is produced by Hsia Kuei (1195 – 1224). Lastly, the broken ink style was made byYü Chien (c. 1230). Motonobu's paintings that were on the sliding panels are now mounted on hanging scrolls. These hanging scrolls include “49 Landscapes with Flowers and Birds.” Also in the Reiun-in monastery are the monumental works of later Kano artists: Eitoku (1543 – 1590) and Sanraku (1559 – 1635). Motonobu had also some paintings in the Yamatoe style, e.g., the set of hand scrolls Seiryōji engi (‘Origins of Seiryōji’, 1515; Kyoto, Seiryōji). These hand scrolls show that he has a mastery of this style and its conventions. Motonobu was a master of many of the major pictorial styles of his time. One of Motonobu's greatest achievements was in the creation of a new technique for painting. This technique formed the basis for the early Kano school style. The technique was known as Wakan, a mixture of Japanese and Chinese painting. This combination had the spatial solidity and careful brushwork techniques of Kanga. It also had some of the characteristics of Yamatoe style, for instance the fine line, decorative patterning. It also had further associations with Yamatoe like the use of colors and gold leaf. The wall panels depicting Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons shows this combination of style. One of these hanging scrolls dates back to c. 1513 (Kyoto, Daitokuji, Daisen'in). The other hanging scroll dates back to 1543–9 (Kyoto, Myōshinji, Reiun’in). He taught other generations everything he learned. This established some creativity and flexibility in the Kano School. He not only did paintings but he applied three different styles of calligraphy. The first, is a formal style known as shintai (new form). The second and more informal form was known as gyōtai (running form). The third form is a cursive style called sōtai (grass form). The Story of Xiang yan (Tokyo, N. Mus.) shows the emergence of Kano style, although, it has an underlying Chinese philosophy to it. But the figure in the foreground is active and the vertical plane makes the painting Japanese. The brushwork and compositional elements also make the painting appear distinctively Japanese.

The

Kano School flourished because of leaders like Motonobu. Motonobu's

reputation, talent and developed organizational skills made this

possible. The school was founded in the fifteenth century but has had a

landmarking impact. The system was patriarchal and modeled after other

guilds before its time. Going from one male in a generation to the

next. Strict teaching made the Kano School a success. Teaching was a

focus in the school and Motonobu stressed this idea. He let others

watch him because he cared about future generations wanting them to develop further his unique

style. Because of his political connections, patronage, organization,

and influence he was able to make the Kano School into what it is

today. The Kano system of workshops has influenced many generations.

The system was responsible for the training of the majority of

painters throughout the Edo period (1615 – 1868).