<Back to Index>

- Chemist Fritz Haber, 1868

- Poet John Milton, 1608

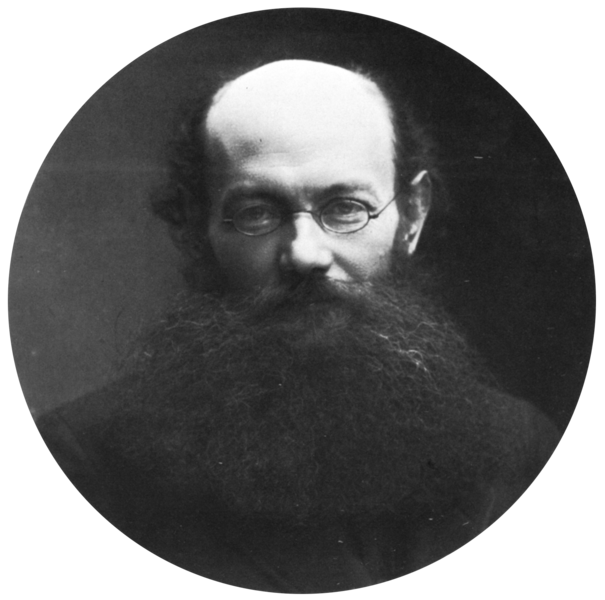

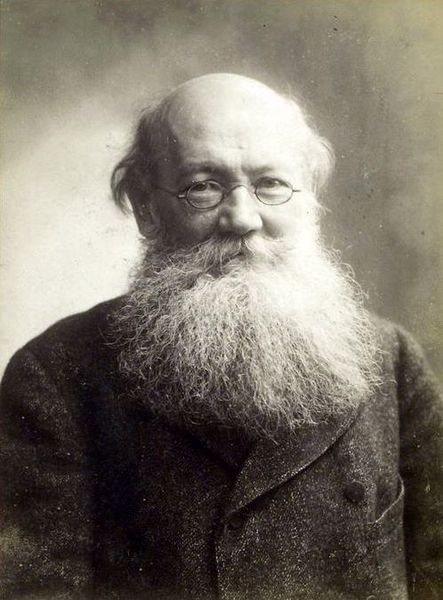

- Anarchist Revolutionary Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin, 1842

PAGE SPONSOR

Prince Peter (Pyotr) Alexeyevich Kropotkin (Russian: Пётр Алексеевич Кропоткин) (9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a zoologist, an evolutionary theorist, geographer and one of the world's foremost anarcho-communists. One of the first advocates of anarchist communism, Kropotkin advocated a communist society free from central government and based on voluntary associations between workers. Because of his title of prince, he was known by some as "the Anarchist Prince". Some contemporaries saw him as leading a near perfect life, including Oscar Wilde, who described him as "a man with a soul of that beautiful white Christ which seems coming out of Russia." He wrote many books, pamphlets and articles, the most prominent being The Conquest of Bread and Fields, Factories and Workshops, and his principal scientific offering, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. He was also a contributor to the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition in writing the article on anarchism.

Peter (or Pyotr) Kropotkin was born in Moscow. His father, Prince Alexei Petrovich Kropotkin, owned large tracts of land and nearly 1200 "souls" (male serfs) in three provinces. Kropotkin's male line traced to the legendary prince Rurik; his mother was the daughter of a Russian general. "[U]nder the influence of republican teachings," he dropped his princely title at the age of twelve, and "even rebuked his friends, when they so referred to him."

In 1857, at age 15, Kropotkin entered the Corps of Pages at St. Petersburg. Only 150 boys — mostly children of nobility belonging to the court — were educated in this privileged corps, which combined the character of a military school endowed with special rights and of a court institution attached to the imperial household. Kropotkin's memoirs detail the hazing and other abuse of pages for which the Corps had become notorious.

In Moscow, Kropotkin had developed an interest in the condition of the peasantry, and this interest increased as he grew older. In St. Petersburg, he read widely on his own account, and gave special attention to the works of the French encyclopædists and to French history. The years 1857 - 1861 witnessed a rich growth in the intellectual forces of Russia, and Kropotkin came under the influence of the new liberal - revolutionary literature, which largely expressed his own aspirations.

In

1862, Kropotkin was promoted from the Corps of Pages to the army. The

members of the corps had the prescriptive right to choose the regiment

to which they would be attached. For some time, he was aide de camp to the governor of

Transbaikalia at Chita. Later he was appointed attaché

for Cossack affairs to the governor general of East Siberia at Irkutsk. Administrative

work was scarce, and in 1864 Kropotkin accepted charge of a

geographical survey expedition, crossing North Manchuria from Transbaikalia to the Amur,

and soon was attached to another expedition which proceeded up the Sungari River into the heart of Manchuria.

The expeditions yielded very valuable geographical results. The

impossibility of obtaining any real administrative reforms in Siberia now

induced Kropotkin to devote himself almost entirely to scientific

exploration, in which he continued to be highly successful. In

1867, he quit the army and returned to St. Petersburg, where he entered

the university, becoming at the same time secretary to the geography

section of the Russian

Geographical Society. In

1871, he explored the glacial deposits of Finland and Sweden for the Society. In 1873, he published an

important contribution to

science, a map and paper in which he proved that the existing maps

entirely misrepresented the physical

features of Asia;

the main structural lines were in fact from south-west to north-east,

not from north to south, or from east to west as had been previously

supposed. During this work, he was offered the secretaryship of the

Society, but he had decided that it was his duty not to work at fresh

discoveries but to aid in diffusing existing knowledge among the people

at large. Accordingly, he refused the offer and returned to St.

Petersburg, where he joined the revolutionary party. He

visited Switzerland in 1872 and became a member of the International

Workingmen's Association (IWA)

at Geneva. It was there that he found that he did not like IWA's style

of socialism.

Instead, he studied the programme of the more radical Jura federation at Neuchâtel and

spent time in the company of the leading members, and definitely

adopted the creed of anarchism. On returning to Russia, he took an

active part in spreading revolutionary propaganda through the nihilist-led Circle of

Tchaikovsky. In 1873

Kropotkin was arrested and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul

Fortress.

He gained notoriety for his widely publicized escape from the prison in

1876, after which he went to England, moving after a short stay to

Switzerland, where he joined the Jura Federation. In 1877 he moved to

Paris, where he helped to start the socialist movement. In 1878 he

returned to Switzerland, where he edited for Jura Federation's

revolutionary newspaper Le

Révolté,

and published various revolutionary pamphlets. He was outspoken in his

beliefs that the peasants were being treated unfairly and deserved to

have the same land as the lords In 1881

shortly after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II,

the Swiss government expelled Kropotkin from Switzerland. After a short

stay at Thonon (Savoy),

he went to London, where he stayed nearly a year, and returned to

Thonon in late 1882. Soon he was arrested by the French government,

tried at Lyon, and sentenced by a police court magistrate (under a

special law passed on the fall of the Paris Commune)

to

five years' imprisonment, on the ground that he had belonged to the

IWA (1883). The French Chamber repeatedly agitated on his behalf, and

he was released in 1886. He settled near London, living at various

times in Harrow – where his daughter,

Alexandra, was born – Ealing and Bromley (6 Cresent Road 1886 - 1914).

He also lived for a number of years in Brighton.

While living in London, Kropotkin became friends with a number of

prominent English speaking socialists, including William Morris and George Bernard

Shaw. In 1902

Kropotkin published the book Mutual Aid: A

Factor of Evolution,

which provided an alternative view on animal and human survival, beyond

the claims of interpersonal competition and natural hierarchy proffered

at the time by some "social

Darwinists", such as Francis Galton. In

the animal world we have seen that the vast majority of species live in

societies, and that they find in association the best arms for the

struggle for life: understood, of course, in its wide Darwinian

sense – not as a struggle for the sheer means of existence, but as

a struggle against all natural conditions unfavourable to the species.

The animal species, in which individual struggle has been reduced to

its narrowest limits, and the practice of mutual aid has attained the

greatest development, are invariably the most numerous, the most

prosperous, and the most open to further progress. The mutual

protection which is obtained in this case, the possibility of attaining

old age and of accumulating experience, the higher intellectual

development, and the further growth of sociable habits, secure the

maintenance of the species, its extension, and its further progressive

evolution. The unsociable species, on the contrary, are doomed to decay. – Peter Kropotkin, Mutual Aid: A Factor of

Evolution (1902), Conclusion. Kropotkin's

authority

as a writer on Russia is generally acknowledged, and he

contributed to many articles. Most of the other 90 articles are about

various aspects of Russian geography. Kropotkin

returned to Russia after the February

Revolution and

was offered the ministry of education in the provisional government; he

rejected the post. His enthusiasm for the changes happening in the Russian Empire turned to disappointment

when the Bolsheviks seized power in the October

Revolution.

"This buries the revolution," he said. He thought that the Bolsheviks

had shown how the revolution was not to be made; by authoritarian

rather than libertarian methods. He had spoken out against

authoritarian socialism in his writings (for example The Conquest of

Bread), making the prediction that any state founded on these

principles would most likely lead to its breakup and the restoration of capitalism.

This prediction preceded the Revolutions of

1989 by nearly 100

years. He died on February 8, 1921, in the city

of Dmitrov, Moscow province, and was buried at the Novodevichy

Cemetery,

Moscow. Anarchists marched in his funeral procession carrying banners

with anti-Bolshevik slogans, at Lenin's approval, since he feared new

unrest otherwise. This was the last march by anarchists

until 1987, when glasnost saw them hold the first open free protest

against Bolshevik state Communism for over sixty years in Moscow. Kropotkin's

inspiration

has reached into the 20th and 21st centuries as a vision of

a new society based on the anarchist principles of anti-statism and

anti-authoritarianism, the communist principles of the publicly owned

means of production and his zoological theories on the mutual aid

between all species and individuals. It is often positioned as a

counter to the thinking of Trotsky, Lenin and Stalin which

tended to imply centralised planning and control. To a large degree

Kropotkin's emphasis is on local organisation, local production

obviating the need for central government. Kropotkin's vision is also

on agriculture and rural life, making it a contrasting perspective to

the largely industrial thinking of communists and socialists. In his

book Mutual Aid: A

Factor of Evolution, Kropotkin explored the widespread use of cooperation as

a survival mechanism in human societies through their many stages, and

animals. Written in accessible language, he used many real life

examples in an attempt to show that the main factor in facilitating

evolution is cooperation between individuals in free-associated

societies and groups, without central control, authority or compulsion. This was in order to counteract the

conception of fierce competition as the core of evolution,

that provided a rationalization for the dominant political, economic

and social theories of the time; and the prevalent interpretations of Darwinism. His

observations of cooperative tendencies in indigenous

peoples, pre-feudal, feudal and

those remaining in modern societies, allowed him to conclude that not

all human societies were based on competition such as those of

industrialized Europe;

and that in many societies, cooperation was the norm between

individuals and groups. He also concluded that in most pre-industrial

and pre-authoritarian societies (where he claimed that leadership,

central government and class did not exist) actively defend against the

accumulation of private property, for example, by equally sharing out,

amongst the community, a person's possessions when he has died; or not

allowing a gift to be sold, bartered or used to create wealth. In

another of his books, The Conquest of

Bread, Kropotkin proposed a system of economics based

on mutual exchanges made in a system of voluntary cooperation. He

believed that should a society be socially, culturally and industrially

developed enough to produce all the goods and services required by it,

then no obstacle, such as preferential distribution, pricing or

monetary exchange will stand as an obstacle for all taking what they

need from the social product. The king pin in this idea is the eventual

abolishment of money or tokens to exchange for goods and services. He

further developed these ideas in Fields,

Factories and Workshops. Kropotkin

points out what he considers to be the fallacies of the economic systems of feudalism and capitalism,

and how he believes they create poverty and scarcity while promoting privilege.

He goes on to propose a more decentralised economic system based on mutual aid and voluntary cooperation,

asserting that the tendencies for this kind of organisation already

exist, both in evolution and in human society. His focus on local production leads to

his view that a country should strive for self-sufficiency –

manufacture its own goods and grow its own food, lessening dependence

on imports. To these ends he advocated irrigation and growing under

glass to boost local food production ability.