<Back to Index>

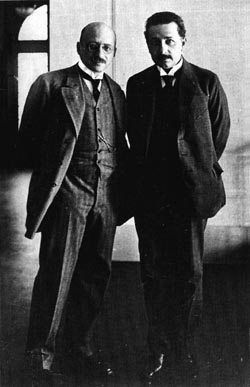

- Chemist Fritz Haber, 1868

- Poet John Milton, 1608

- Anarchist Revolutionary Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin, 1842

PAGE SPONSOR

Fritz Haber (9 December 1868 – 29 January 1934) was a German chemist, who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918 for his development for synthesizing ammonia, important for fertilizers and explosives. Haber, along with Max Born, proposed the Born – Haber cycle as a method for evaluating the lattice energy of an ionic solid. He has also been described as the "father of chemical warfare" for his work developing and deploying chlorine and other poisonous gases during World War I.

Haber was born in Breslau, Germany (now Wrocław, Poland), into a Hasidic family. His was one of the oldest families of that town. Haber later converted from strict Judaism to Christianity. His mother died during childbirth. His father was a well known merchant in the town. From 1886 until 1891, he studied at the University of Heidelberg under Robert Bunsen, at the University of Berlin (today the Humboldt University of Berlin) in the group of A.W. Hofmann, and at the Technical College of Charlottenburg (today the Technical University of Berlin) under Carl Liebermann. He married Clara Immerwahr during 1901. Clara was also a chemist and an opponent of Haber's work in chemical warfare. Following an argument with Haber over the subject, she committed suicide by shooting herself in the heart. Their son, Hermann, born in 1902, would later also commit suicide because of his shame over his father's chemical warfare work. Before starting his own academic career, he worked at his father's chemical business and in the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zürich with Georg Lunge.

During his time at University of Karlsruhe from 1894 to 1911, he and Carl Bosch developed the Haber process, which is the catalytic formation of ammonia from hydrogen and atmospheric nitrogen under conditions of low temperature and high pressure. In 1918 he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for this work.

The Haber - Bosch process was a milestone in industrial chemistry, because it divorced the production of nitrogen products, such as fertilizer, explosives and chemical feedstocks, from natural deposits, especially sodium nitrate (caliche), of which Chile was a major (and almost unique) producer. The sudden availability of cheap nitrogenous fertilizer is credited with averting a Malthusian catastrophe. Naturally extracted nitrate production in Chile fell from 2.5 million metric tonnes (employing 60,000 workers and selling at $45/tonne) n 1925 to just 800,000 tonnes, produced by 14,133 workers, and selling at $19/tonne in 1934.

He was

also active in the research of combustion reactions, the separation of gold from sea water, adsorption effects, electrochemistry,

and free radical research (see Fenton's reagent).

A large part of his work from 1911 to 1933 was done at the Kaiser Wilhelm

Institute for Physical Chemistry and Elektrochemistry at Berlin - Dahlem.

In 1953, this institute was renamed for him. He is sometimes credited,

incorrectly, with first synthesizing MDMA (which was first

synthesized by Merck KGaA chemist Anton

Köllisch in 1912). Haber

played a major role in the development of chemical

warfare in World War I. Part of this work included the

development of gas masks

with absorbent filters. In addition to leading the teams developing chlorine gas and other deadly gases

for use in trench warfare,

Haber

was on hand personally to aid in its release despite being

proscribed by the Hague Convention of 1907 (to which Germany was a

signatory). Future Nobel laureates James Franck, Gustav Hertz,

and Otto Hahn served as gas troops in Haber's unit. Gas

warfare in WW I was, in a sense, the war of the chemists, with Haber

pitted against French Nobel laureate chemist Victor Grignard.

Regarding

war and peace, Haber once said, "During peace time a

scientist belongs to the World, but during war time he belongs to his

country." His wife, Clara Immerwahr,

a fellow chemist, opposed his work on poison gas and

committed suicide with his service revolver in their garden, possibly

in response to his having personally overseen the first successful use

of chlorine at the Second Battle

of Ypres on 22 April

1915. She shot herself in

the heart on 15 May, and died in the morning. That same morning, Haber

left for the Eastern Front to oversee gas release

against the Russians.

Haber was a patriotic German who was proud of his service during World War I,

for which he was decorated. He was even given the rank of captain by the Kaiser,

rare for a scientist too old to enlist in military service. In

his studies of the effects of poison gas, Haber noted that exposure to

a low concentration of a poisonous gas for a long time often had the

same effect (death) as exposure to a high concentration for a short

time. He formulated a simple mathematical relationship between the gas

concentration and the necessary exposure time. This relationship became

known as Haber's rule. Haber

defended gas warfare against accusations that it was inhumane, saying

that death was death, by whatever means it was inflicted. During the

1920s, scientists working at his institute developed the cyanide gas formulation Zyklon B,

which was used as an insecticide,

especially as a fumigant in grain stores but also to poison prisoners in gas chambers at Auschwitz, Birkenau,

and other extermination

camps. In

the 1920s, Haber exhaustively searched for a method to extract gold

from sea water, and published a number of scientific papers on the

subject. However, after years of research, he concluded that the

concentration of gold dissolved in sea water was much lower than those

concentrations reported by earlier researchers, and that gold

extraction from sea water was uneconomic. Haber's

genius was recognized by the Nazis, who offered him special funding to

continue his research on weapons. However, as a result of fellow Jewish

scientists having already been expelled from working in that field, he

left Germany in 1933. His Nobel Prize winning work in chemistry, and

subsequent contributions to Germany's war efforts in the form of

chemical fertilizers, explosives and poison munitions, were not enough

to prevent eventual vilification of his heritage by the Nazi regime. He moved to

Cambridge, England, along with his assistant J J Weiss,

for a few months, during which time Ernest

Rutherford pointedly

refused to shake hands with him, due to his involvement in poison gas

warfare. Haber was offered by Chaim Weizmann the position of director at

the Sieff Research Institute (now the Weizmann

Institute) in Rehovot,

in Mandate

Palestine, and accepted it. He started his voyage to what is

today Israel in

January 1934, after recovering from a heart attack. However, his ill

health overpowered him and on January 29, 1934, at the age of 65, he

died of heart failure in a Basel hotel, where he was resting

on his way to the Middle East. He was cremated and his ashes,

together with Clara's ashes, were buried in Basel's Hornli Cemetery. He bequeathed his extensive

private library to the Sieff Institute. Haber's

immediate family also left Germany. His second wife, Charlotte, with

their two children, settled in England. Haber's son from his first

marriage, Hermann, emigrated to the United States during World War II.

He committed suicide in 1946. Members of Haber's extended family died in concentration

camps.

One of his children, Ludwig ("Lutz") Fritz Haber (1921 – 2004), became

an

eminent historian of chemical warfare in World War I, and published a

book called The

Poisonous Cloud (1986). Haber

received

much criticism for his involvement in the development of

chemical weapons in pre-World War II Germany both by contemporaries and

by modern day scientists. The

research results show the ambiguity of his scientific activity: On the

one hand, through the development of ammonia synthesis (to manufacture

explosive) or a technical process for the manufacture and use of poison

gas in warfare as it has become possible on an industrial basis. On the

other hand, without this knowledge and ability the diet of today's

humanity would not be possible. The annual world production of

synthesized nitrogen fertilizer is currently more than 100 million

tons. The food base of a half of the current world population is based

on the Haber - Bosch process.